James Joyce: Notes (6) - Joyce’s People [1/1]

| Textual History | Literary Figures | Joyce’s People | Sundry Remarks |

| Index |

| College friends |

[ For information on Alfred Byrne, Lord Mayor of Dublin and character in The Cat and the Devil/The Cat of Beaugency, see attached. ]

Irish Figures

| College friends: The chief of Joyce’s friends and associates at University College who modelled for characters in his autobiographical fiction were Vincent Cosgrave (‘Lynch’ in A Portrait); John Francis (“Jeff”) Byrne [1879-1960], later a journalist in America (‘Cranly’ in A Portrait and Ulysses); George Clancy [d.1921], a naïve exponent of Irish-Ireland purismo who was later assassinated by the Black and Tans while Mayor of Limerick (‘Davin’ in A Portrait); Francis Skeffington [d.1916], pacificist-feminist-vegetarian and sporter of knickerbockers, who was likewise murdered while in custody by British soliders after he quixotically attempted to prevent looting in the 1916 Rising (McCann in A Portrait); and finally Constantine Curran [1983-1972], later Registrar of Supreme Court and author on Georgian Dublin architecture who produced the most complete memoir of their college days excepting Stanislaus Joyce’s. Joyce narrowly lost elections for the posts of Treasure and Auditor to Louis J. Walsh and Hugh Kennedy - both of whom had distinguished careers after - in March 1899 and May 1900. John Rudolf Elwood [d.1931?] was a medical student who eventually qualified as an apothecary (Temple in A Portrait) |

|

| See also ... |

|

[ top ]

| Identity of E.C. [Emma Clery]: |

| Stephen’s bien aimée in A Portrait of the Artist has been identified with Mary Sheehy by Richard Ellmann and others. It is probable that the character is composite since some episodes concerning her in A Portrait - notably the circumstances surrounding the “Vilanelle” - are clearly associated with Mary Sheehy in Stanislaus’s account of Joyce’s relations with that family in My Brother’s Keeper (1958, p.157.) |

|

| Peter Costello has suggested that the real Emma was a contemporary student called M[ary] E[lizabeth] Cleary, later Mrs. Meehan. When asked by her son, Prof. James Meehan of UCD, ‘she said she had known James Joyce [...] but had found him to be a common, vulgar person’ and further admitted that he ‘had been keen on her’. (See Peter Costello, James Joyce: The Years of Growth 1882-1915, London: Kyle Cathie; NY: Roberts Rinehart 1992, p.189.) |

|

[ top ]

John Stanislaus Joyce:

|

| [ The above notice has been extracted from an essay by Bruce Stewart in the IASAIL Papers (Rodopi 1996). ] |

[ top ]

May Joyce (1) Joyce’s mother is portrayed in Ulysses as Mary Dedalus (née Goulding) and the date of her death set on [24] June 1903 - a little earlier than its actual occurrence which fell on 13 August 1903. See “Ithaca” chapter: ‘What inchoate corollary statement was consequently suppressed by the host [Bloom]? / A statement explanatory of his absence on the occasion of the interment of Mrs Mary Dedalus, born Goulding, 26 June 1903, vigil of the anniversary of the decease of Rudolph Bloom (born Virag).’ (Ulysses, Bodley Head Edn., 1960, p.815.)

May Joyce (1) Joyce’s mother, Mary-Jane Murray, met his father in the choir of Rathmines Church. (Information supplied by Anne-Marie D’Arcy on Facebook - 174.07.2016.)

May Joyce (2) wrote to his son: ‘My dear Jim if you are disappointed in my letter and if as usual I fail to understand what you wish to explain, believe me it is not from any want of a longing desire to do so and speak the words you want but as you so often said I am stupid and cannot grasp the great thoughts which are yours much as I desire to do so. Do not wear your soul out with tears but be brave and look hopefully to the future.’ (Letters, Vol. II, p.2; quoted in Richard Ellmann, ed., Selected Letters, 1975, Intro., pp.xvii-iii, with the comment: ‘Her reply to many such pleas is a naked statement of [xvii] maternal love ... To his harshness, and the defence of harshness by reference to his art ... May Joyce responded with a faultless simplicity’, pp.xvii-iii.)

Richard Ellmann [Introduction, Selected Letters 1975] begins by describing the ‘moral note’ of Joyce’s ‘extraordinary letter’ written to his mother written from Paris soon after his twenty-first birthday [2 Feb. 1903] as ‘equivocal’ (p.xvi) and adds after quoting it in full: ‘[.. ] This letter does not inspire an instant sympathy [...] Its young writer is not self-sacrificing, not virtuous, not sensible, although he waves his hand distantly at these attributes. At first we see only self-pity and heartlessness in this assertion of his own needs as paramount. He takes unfair advantage of the fact that his mother’s love is large enough to accept even the abuse of it. Yet there are twinges of conscience, sudden moments of concern for her, and there is evidence that he depends upon her for more than money, as if he could not live outside the environment of family affection, badly as he acts within in. [...] Throughout the letter the emphasis is on his lenten fasts for his art. In other correspondence with her too, Joyce asks his mother to approve his artistic plans while he is fully aware that they are beyond her grasps, just as later he makes the same demands of his less educated wife. He writes that he will publish a book of songs in 1907, a comedy in 1913, and an aesthetic system five years after that. ‘This must interest you!’ he insists, fearful that she may regard him as a starveling rather than as a starved hero. Her reply to many such pleas is a naked statement of [xvii] maternal love [Quotes as above: My dear Jim ... If you are disappointed in my letter]. To his harshness, and the defence of harshness by reference to his art ... May Joyce responded with a faultless simplicity.’ (Sel. Letters, Faber 1975, pp.xvii-iii.)

Richard Ellmann [James Joyce, rev. edn. 1983, p.136]: ‘His father became increasingly difficult to handle as his drinking caught up with the pace of May Joyce’s decay. One hopeless night he reeled home and in his wife’s room blurted out “I'm finished. I can’t do any more. If you can’t get well, die. Die and be damned to you!’ Stanislaus screamed at him, “You swine!” and went for him murderously, but stopped when he say his mother struggling frantically to get out of bed and intercept him. James led his father out and langed to lock him in another room. [n.24] Shortly after, tragedy yielded to absurdity. John Joyce was seen disappearing around the corner, having connived to escape out a second-floor window. [n.25]

‘May Joyce died on August 13, 1903, at the early age of forty-four. [n.26] In her last hours she lay in a coma, and the family knelt about her bed, praying and lamenting. Her brother John Murray, observing that neither Stanislaus nor James was kneeling, peremptorily ordered them to do so. Neither obeyed. [Interview with Mrs Monagham [sic], 1953; MBK.] Mrs Joyce’s body was taken to Glasnevin to be buried, and Joyce Joyce wept inconsolably for his wife and himself. “I'll soon be stretched beside her,” he said. “Let Him take me whenever he likes.” [Ulysses; confirmed by daughters to Ellmann] His feelings were genuine enough, and when Stanislaus, goaded to fury by what he regarded as his father’s hypocritical whinings, denounced him for all his misdeeds, John Joyce listened quietly and merely said, “You don’t understand, boy.” James and Margaret got up at midnight to see their mother’s ghost, and Margaret thought she saw her in the brown habit in which she was buried. [MBK] The whole family was dismayed and sad, but especially Mabel, the youngest, not yet ten years old. James sat beside her on the stairs, his arm around her saying, “You must not cry like that because there is no reason to cry. Mother is in heaven. She is far happier now than she has ever been on earth, but if she sees you crying it will spoil her happiness. You must remember that when you feel like crying. You can pray for her if you wish, Mother would like that. But don’t cry any more.” [Told to Rev. Godfrey Ainsworth in an interview with Mabel and communicated to Ellmann by letter in 1980 - i.e., added in rev. edn.]

‘A few days later he found a packet of love letters from his father to his mother, and read them in the garden. “Well?” asked Stanislaus. “Nothing,” James replied. He had changed from son to literary critic. Stanisalus, incapable of such rapid transformations, burnt them unread. [Stanislaus, Diary; quoted in Intro. to MBK] Joyce was not demonstrative, but he remembered his vigils with Margaret and wrote in Ulysses: “Silently, in a dream she had come to him after her death, her wasted body within its loose brown graveclothes ...; he spoke also of “Her secrets: old feather fans, tasseled [sic] dancecards, powdered with musk, a gaud of amber beads in her locked drawer,” and he summed up his feelings in the poems “Tilly” which he did not publish until 1927. [MBK - My Brother’s Keeper. Above cites dual pag. for older and newer eds.]May Joyce (3) - as her final illness advanced, her increasingly alcoholic husband shouted ‘If you can’t get well [...] die and be damned to you!’ - only to be screamed at by Stanislaus, ‘You swine!’ before being led off to another room by James. (See Stanislaus Joyce, My Brother’s Keeper, London: Faber & Faber 1958, p.230 - and note that Ellmann erroneously places this quotation on p.229 (James Joyce, 1965 Edn, p.141). Ellmann follows it with a quotation from an interview with Eva Joyce conducted by Niall Sheridan in 1949 during which she told that Mr Joyce completed the episode by making an escape out a second floor window. (Ellmann, op. cit., p.141.)

May Joyce (4) - acc. Stanislaus Joyce: ‘My mother had become for my brother the type of the woman who fears and, with weak insistence and disapproval, tries to hinder the adventures of the spirit. Above all, she bejcame for him the Irishwoman, the accomplice of the Irish Catholic Church, which he called the scullery-maid of Christendom, the accomplice, that is to say, olf a hybrid form of religion produced by the most unenlightened features of Catholicism [...] the accomplice, in fine, of the vigilant and ruthless enemy of free thought and the joy of living.’ (My Brother’s Keeper, London: Faber & Faber 1959, p.234.) [In the ellipsis, Stanislaus suggets that the Catholic Church in Ireland was trying to match the Puritanism of the English so as not to appear immoral.

May Joyce (5) - remarks by Marvin Magalaner: ‘As a child Joyce had the standard, normal Catholic upbringing of an Irish youngster of the 1880s. His good-tempered, pious mother personifies the strengths and weaknesses of Irish Catholicism during that period: her skill in music brought remarkable beauty to the middle-class suburban hearth; her deep religious sense, not so much a conviction as an intuition, gave her the emotional strength to compensate for physical weakness; her routine adherence to the demanding ritual calendar supplied a center of meaningful activity about which family life and religious hope might revolve. If she worried out loud, it was not about creditors or bedbugs-matters of immediate concern to Stephen Dedalus - but about the irreverence or profanity of her brood, the external signs of troubled spirits. From such maternal singleness of mind, one might have expected priests and nuns to come. One of Joyce’s sisters did enter a religious order. And the stress on respectability through religious conformity brought Joyce very close to a Jesuit novitiate. (‘The Problem of Biography’, in Magalaner & Richard M. Kain, James Joyce: The Man, The Works, The Reputation [1956] (London: John Calder 1957), pp.15-43; pp.38-39.)

May Joyce (6): Joyce’s mother was cultivated enough to called Oliver St. John Gogarty ‘Sir Peter Teazle’ after the medical character in a play of Sheridan on account of his dapper appearance. (See Ellmann, James Joyce, 1965 Edn., p.141.)

Ellmann on Joyce & motherhood (7): ‘Joyce seems to have thought with equal affection of the roles of mother and child. He said once to Stanislaus about the bond between the two, “There are only two forms of love in the world, the love of a mother for a child and the love of a man for lies.” In later life, as Maria Jolas remarked, “Joyce talked about fatherhood as if it were motherhood.” he seemed to have longed to establish in himself all aspects of the bond of mother and child. He was attracted, particularly, by the image of himself as a weak child cherished by a strong woman, which seems closely connected wit the images of himself as victim, whether as a deer pursued by hunters, as a passive man surrounded by burly extroverts, as a Parnell or a Jesus among traitors. His favourite characters are those who in one way or another retreat before masculinity, yet are loved regardless by motherly women. (James Joyce, 1965 Edn. p.303; see longer quotations from the biography - in RICORSO > Criticism > Major Writers - infra.)

[ top ]

Josephine Murray [Aunt Josephine] was the recipient of letters from Joyce asking for details of Dublin, e.g., ‘please send me a bundle of other novelettes and any penny hymnbook you can find’ (5 Jan. 1920; Letters, I, p.135); or, ‘[would it be] possible for an ordinary person to climb over the area railings of No. 7 Eccles street’ (2 Nov. 1921; Letters, I, p.175; both the foregoing quoted in Stephen Heath, ‘Ambiviolences: Notes for reading Joyce’, in Attridge & Ferrer, eds., Post-structuralist Joyce, Cambridge UP 1984, p.64, n.36.) Note: Heath remarks that these requests and their corresponding outcomes in the text ‘do not identify Ulysses as a prime example of realist writing.’ (Idem.)

[ top ]

Nora Joyce - 1: b. 21 March 1884 d.10 April 1951; dg. of Thomas Barnacle, a baker, and Annie Barnacle, both of Galway; left Galway early 1904 following family row; worked as chambermaid at Finn’s Hotel, 1 & 2 Leinster St.; encountered by Joyce in the street in June and agreed to meet some days later on 14 June; failed to show and rearranged for 16 June when they first walked out together - the date being commemorated in the setting of Ulysses. (See Selected Letters, ed. Richard Ellmann, 1975, p.21, n.7.)

Nora Joyce - 2: ‘Pretty little story, eh?’ - Joyce recounts details of her Galway childhood including her relations with Michael Bodkin, a protestant young man called Mulvey, a young priest, and an uncle who beats her with a stick. (Letter of 3 Dec. 1904; Selected Letters, 1975, p.45).

Nora Joyce - 3: Take me!: Joyce wrote to her, ‘O take me into your soul of souls and then I will become indeed the poet of my race.’ (7 Sept. 1909; Selected Letters, p.169). Also: ‘Take me into the dark sanctuary of your womb. Shelter me, dear, from harm!’ (24 Dec. 1909; SL, p.195). Cf. ‘Take me, save me, soothe me, O spare me!’ ( Paris, 1924; Pomes Penyeach [1927], London: Faber 1966, p.14; Poems and Shorter Writings, 1991, p.63.)

Nora Joyce - 4: Joyce wrote to Nora on 19 Nov. 1909: ‘I have loved in her the image of the beauty of the world, the mystery and beauty of life itself, the beauty and doom of the race of whom I am a child, the images of spiritual purity and pity which I believed in as a boy. / Her soul! Her name! Her eyes. They seem to me like strange beautiful blue wild-flowers growing in some tangled, rain-drenched hedge. and I have felt her soul tremble beside mine, and have spoken her name softly to the night, and have wept to see the beauty of the world passing like a dream behind her eyes.’ (Selected Letters, ed. Richard Ellmann, 1975, p.179.)

Nora Joyce - 5: Nora prevented Miss Weaver from donating the MS of Finnegans Wake to the National Library of Ireland since the Irish government had refused to repatriate his body. (See Stan Gebler Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist, 1975.)

Nora Joyce - 6: Did she or didn’t she?: Morris Beja appears to accept that Vincent Cosgrave seduced Nora and that Cosgrave made the claim in talking to Joyce in 1909 out of annoyance at appearing as Lynch in Stephen Hero. (See Ian Pindar, review of Beja, James Joyce: A Literary Life, Macmillan 1992, in Times Literary Supplement, 18 Dec. 1992 [Note: Pindar went on to write A Life of James Joyce, with an intro. by Terry Eagleton, London: Haus Publ. 2004.]

Nora Joyce (namesake) was the mother of Adolph Menjou, an American actor known for his moustache and his appearances in numerous films including Chaplin’s A Woman of Paris (1927) and Kubrik’s Paths of Glory (1958). Nora [née Joyce] (1869-1953) was born in Galway. She married Albert Menjou (1858-1917) and had two sons with him, Adolph (1890-1963) and Henry Arthur (1891-1956), Adolph was raised Catholic, attended the Culver Military Academy, and graduated from Cornell University with a degree in engineering. Attracted to the vaudeville stage, he made his movie debut in 1916 in The Blue Envelope Mystery. He served as a captain in the United States Army Ambulance Service during World War I and later participated enthusiastically in the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1947 and some years following. (See Wikpedia - online; accessed 24.11.2021.)

[ top ]

Lucia Joyce (1): Lucia wrote to her father, ‘If I should ever go away, it would be to a country which belongs in a way to you, isn’t it, father?’ (Quoted in Kevin Kiely, review of works on Joyce, in Books Ireland, Oct. 1998, p.262.)

[Note: No concerted attempt is made here to list the growing number of studies of Lucia - including biographies and novels.]

Lucia Joyce (2): See Caitlín Murphy, A is for Everything (Project Cube, Aug. 2002), is an 80-minute exploration of the minds of Lucia, schizophrenic daughter of James Joyce, and Suzanne, long-time partner and eventual wife of Samuel Beckett, who talk through their experiences of life in the shadows of genius. (The Irish Times, Wed, 31 July 2002.)

[ top ]

Stephen Joyce: Stephen James Joyce, son of Giorgio Joyce with Helen Kastor Fleischmann, and the grandson of James Joyce, was born on 15 Feb. 1932 and was the recipent of the letter upon which The Cat and the Devil (1964) is based. He attended school in Andover, Hants. - Harcourt Prep School? - and graduated from Harvard and worked with UNESCO, chiefly in Africa, until 1991. He assumed control of the James Joyce Estate in the early 1990s, since which time he has been a thorn in the side of students and writers on Joyce in his determination to protect the secrecy of the family and particularly the sexual relationship of his grandparents and the management of Lucia’s insanity. Stephen Joyce’s resistance to the use of texts controlled by the Joyce estate which he governs gave rise to a series of attacks in journalism and scholarship exemplified by an article by D. T. Max under the title ‘The Injustice Collector: Is James Joyce’s grandson suppressing scholarship?’, in The New Yorker (19 June 2006) - in which the following is alleged: ‘at a Bloomsday symposium in Venice, Stephen announced that he had destroyed all the letters that his aunt Lucia had written to him and his wife. He added that he had done the same with postcards and a telegram sent to Lucia by Samuel Beckett, with whom she had pursued a relationship in the late nineteen-twenties. / “I have not destroyed any papers or letters in my grandfather’s hand, yet,” Stephen wrote at the time. But in the early nineties he persuaded the National Library of Ireland to give him some Joyce family correspondence that was scheduled to be unsealed. Scholars worry that these documents, too, have been destroyed.’

Stephen inherited half of the estate at the death of Lucia in 1982; at the death of Giorgio in 1993, half of the remainder devolved on him, the other half going to Hans Jahnke and his sister Evelyn, being the children of Giorgio’s second wife Asta. Following the case brought against Danis Rose arising from edition of Ulysses issued by Lilliput, Jahnke parted with his share to Stephen to cover legal costs incurred. Other matters described include Stephen Joyce’s measures to preclude publication of Joycean text by Michael Groden (viz., a database on internet), Carol Loeb Shloss (in her life of Lucia), Danis Rose, and others. The article ante-dates the resolution of the Shloss case

| D. T Max writes in The New Yorker (19 June 2006): |

|

| See copy of full article in Library > Criticism > Reviews - via index or as attached. |

Further: Max discusses Richard Ellmann’s circumvention of Joyce’s and the estate’s desire to keep the so-called “black letters” of 1909 to Nora private (published unexpurgated in the Selected Letters, 1979) and gives an account of Joyce’s close relationship with Stephen Joyce as a child: ‘The birth of Stephen came soon after the death of Joyce’s father, whom Joyce had romanticized as the source of his talent. Joyce commemorated these events in the poem “Ecce Puer”, which begins, “Of the dark past / A boy is born; / With joy and grief / My heart is torn.” Stephen - German Jewish on his mother’s side, Irish on his father’s - was a beautiful baby. His mother, Helen, in an unpublished memoir that is housed in the archives of the University of Tulsa, describes him as "a handsome lively, wavy haired blonde, with bright blue eyes not as dark as his fathers and rosy cheeks and a bright smile (my smile, I think).” Joyce put the boy on his lap and told him stories. In 1936, he wrote Stephen a children’s story, The Cat and the Devil. Helen, in her memoir, captures their growing rapport: “As Stevie grew older I loved to watch him crawling onto his grandfather’s knee and asking him grave little questions. His serious childish face was charming to see as he listened to the slow and painstaking answers that [his grandfather] gave him in his slow careful Dublin drawl. [Joyce] was infinitely patient with him and was always willing to stop and talk to him or to answer as he grew older his incessant “whys.” The answers needless to say were always wonderful ones.”’

Further [after the breakdown of his parents marriage]: ‘He [Stephen] and Joyce took regular walks along the Zürichsee. Joyce bought him a box of toy soldiers. Helen recalls in her memoir, "I do not think that Stephen will ever forget his famous grandfather and their relationship was a deep and lovely one." Even now, when Stephen has to make important decisions about the estate, he sometimes goes to Joyce’s grave to consult with him.”

[ top ]

Eileen Joyce [Schaurek] - Anne Enright gives an account of the suicide of her husband Frantisek and Joyce’s reaction to it - including his inability to tell her it had happened when he passed through his home in Paris on her way back from Dublin to Trieste - with details about her subsequent life in Dublin when she worked as a translation clerk in the Irish Sweepstake and had a house in Bray and a flat in Dublin - at the former of which she hosted Lucia and suffered damage to the floor when the latter lit a fire on it. Eileen’s daughter Bozena is he source of much of this information:

|

| —Enright, ‘Priests in the Family’, “Diary” in London Review of Books, 18 Nov. 2021 - as attached.) |

Mr Alfred Hunter (1): Ellmann calls him ‘a dark complexioned Dublin Jew ... who was rumoured to be a cuckold’, and relates that Joyce asked Stanislaus (Letter of 3 Dec. 1906) and, later, Aunt Josephine [Murray] to send all the details they could remember about him [James Joyce, 1965 Edn., pp.238, 385]. Joyce had met Hunter twice. Ellmann also gives an account in a footnote of one Morris Harris who was the object of a divorce petition by his wife Kathleen Hynes Harris, he being a sacerdotal [Jew] aged 85 and she a younger woman who accused him of having an affair with his housekeeper (aetat. 80), indecency in the dining room, relations with little girls, and putting excrement on her nightgown.’ (Ibid., pp.238-39, n.)

|

See Terence Killeen, ‘Myth and Monuments: The Case of Alfred H. Hunter’, in Dublin James Joyce Journal, No. 1 (2008), 47-53; p.1 |

|

| —Available at MUSE online; accessed 29.05.1014. |

Mr Alfred Hunter (2): Ellmann considers that in making Bloom an advertising canvasser Joyce had someone other than Hunter in mind, viz., the original of C. P. M’Coy in “Grace”, being Charles Chance, whose wife sang soprano in concerts under the name of Madame Marie Tallon. M’Coy is identified as a clerk on the Midland Railway, an ad. canvasser for The Irish Times and the Freeman’s Journal, a town traveller for a coal firm, a private enquiry agent [detective], a clerk in the sub-sherriff’s office, and secretary to the City Coroner. (James Joyce, [1965] pp.385-86.) Ellmann further cites a Bloom who worked as a dentist in Clare St. in 1903-04 and converted to Catholicism to marry; also his son Joseph, a dentist, renowned as a wit, and finally another Bloom who was tried for the murder of a photographer’s model in Wexford in what was planned as a double suicide, inscribing the word Love (written Loive) in his own blood on the wall. (JJ, 386.) In Ulysses he deliberately gives M’Coy a wife who is in competition with Marion [Molly] Bloom. Another model for Molly was Mrs. Nicolas Santos, wife of a fruitshop owner of that name in Trieste and later in Zurich [sic]; it was an open secret in the Joyce family that Senora Santos was a model for Molly. ‘But the seductiveness of Molly came, of course, from Signorina [Amelia] Popper.’ (JJ, [1959,] 387.)

Note: Bloom’s height (5’ 9”) and weight (11 stone 4lb.) are those of J. F. Byrne as shown on the scale which he and Joyce used to measure themselves during the evening walk on 8 Sept. 1909 when Joyce went round to Byrne’s home at 7 Eccles St. to thank him again for his support when Cosgrave tricked him into believing that he, Cosgrave, had had an affair with Nora. On returning home at 3 a.m. after the walk, Byrne found that he didn’t have his door-key and let himself into the house by lowering himself to the area and entering through the side-door (i.e., the kitchen door beneath the steps] (See Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, 1984 Edn., p.290.)

Note further that the episode in A Portrait of the Artist in which Stephen talks with Fr Darlington, the Dean of Studies (now chiefly identified with the word ‘tundish’), actually happened to J. F. Byrne who related it to Joyce and was displeased to find his innocuous account of the priest lighting a fire had been converted into a reflection on Stephen’s strained relations with Church. (See Ellmann, op. cit., p.298, citing The Silent Years.)

Mr Alfred Hunter (3): Peter Costello corrects Ellmann in asserting that Joyce and his father believed Hunter to be Jewish on account of his complexion, though in fact he was a Presbyterian from Belfast whose father had a shoe shop in Dublin, and who became a nominal Catholic on marrying a Catholic wife, she turning out to be an alcoholic who sold all the furniture for drink on numerous occasions. In 1904 he resided at 28 Ballybough Rd. and latterly 23 Gt. Charles St., where he died, 12 Sept. 1926 [aetat. 60], ‘in a tumbling Dublin tenement, quite ignorant in his poverty of the character he had inspired.’ (The Years of Growth, London: Kyle Cathie 1992, p.19.) Costello relates that it was Hunter who picked Joyce up when he got involved in a fracas in the Kips on a night between 16th and 19th September 1904 and took him home either to his house on Ballybough Rd. or to his uncle William’s in North Strand where he was staying (ibid., pp.230-31.) Costello further identifies one Joseph Bloom, the brother of the dentist in Clark St. [sic for Clare St.] and son of Mark Bloom; Joseph was living at 38 Lombard St. between 1891 and 1906 - one of the former addresses that Joyce gave to Leopold gives Bloom. (p.68.) Costello adds that Joyce enquired of A. J. [Con] Leventhal if the musical Blooms of Lombard street were still there and learnt that they were not (idem)

Mr Alfred Hunter (4): Ellmann does not cite Hunter as the rescuer of Joyce in Nighttown when he was assaulted by two soldiers while Cosgrave stood by in September 1904. Peter Costello does however (The Years of Growth, pp.230-31). Ellmann, on the other hand, mentions the occasion when Joyce was mugged in Rome on a drunken spree immediately before departure from Rome to Trieste. According to Ellmann, this event provided the clue Joyce needed for the similar episode in Ulysses when Bloom rescues Stephen. Ellmann writes: ‘In the resulting hubbub he would have been arrested, as when he first arrived in Trieste in 1904, if some people in the crowd had not recognised him and taken him home, a good deed which he reproduced at the end of the Circe episode in Ulysses.’ (JJ, 1965, p.251). On the evidence it would seem likely that Costello’s insistence that Hunter was in Night-town is mistaken. [Viz., proximity of Nighttown (“Monto’) to Ballybough Rd., in N. Dublin

Alfred Hunter (5): the belief that Joyce based Bloom (in Ulysses) on one Alfred Hunter, a commercial traveller who “rescued” him [Joyce] after a fracas in Nighttown and brought him home to recuperate in the small hours which is promulgated in Ellmann’s life (James Joyce, 1957) derived from information supplied to the biographer by William D’Arcy of Dublin in the 1950s. This information - the reliability of which Ellmann tended to doubt - has been subjected to close interrogation by Terence Killeen in ‘Marion Hunter Revisited’ (Dublin James Joyce Journal, 3, 2011; and see Killeen’s review of Gordon Bowker, Joyce: A Biography, in The Irish Times, 28 May 2011, Weekend, p.12).

Note: Joyce did write to Stanislaus specifically seeking information about Alfred Hunter in a letter of 3 Dec. 1906. Hunter has been identified by Peter Costello in James Joyce: The Years of Growth 1882-1915 (1992) as a Presbyterian and a commercial traveller from Belfast who turned Catholic to marry a Dublin woman who later cuckolded him. Hunter, who had an address at 28 Ballybough Rd. in 1904, apparently died in poor circumstances at 23 Gt. Charles St. on 12 Sept. 1926 [aetat. 60].

Further reading: A. Nicholas Fargnoli & Michael Patrick Gillespie, James Joyce A to Z: An Enclyclopaedic Guide to his Life and Work (London: Bloomsbury 1995); Terence Killeen, ‘The Case of Alfred H. Hunter’, in Dublin James Joyce Journal, I (Dublin 2008), pp.47-53

Alfred Hunter (6) - see Marilyn Reizbaum, James Joyce’s Judaic Other (Stanford UP 2009): ‘Ellmann, among others, documented Jewish prototypes of Bloom as Alfred H. Hunter of Dublin, Italo Sveno (Ettore Schmitz) and Teodore Mayer [ed. of Piccolo della Sera] of Trieste, and Ottocaro Weiss of Zurich. Of these, Hunter was in fact not a Jew, although Joyce might have thought him Jewish because of his physical type (as he similarly assumed of Martha Fleischmann), and perhaps, as Michael Seidel has said of Joyce’s use of certain sources, because for Hunter to be Jewish corroborated the ‘wishmarks’ of his imagination” (Epic Geography, 19.) [...] There are two significant traits that Hunter contributed to Bloom’s character: first, it was thought that Hunter was a cuckhold, and second, on June 22 1904, according to Ellmann, Hunter rescued Joyce from a fracas involving a girlfriend of another man, took him to his house, and tended to his [23] wounds. latter incident would have provided for the scene at the beginning of Eumaeus where Bloom does the same for Stephen.) The other Dublin source for Bloom’s surname, at least, was the family of Blooms who were dentists and with whom Joyce was familiar.’ (pp.22-23.) [See further under Commentary, supra.]

Fr. John Conmee - Conmee, Rev John SJ (1487-1910), rector of Clongowes, 1885-91; Prefect of Studies at Belvedere, 1891-92; prefect of Studies at UCD, 1893-95; superior of St. Francis Xavier Church, 1897-1905; provincial, 1905-09; rector of Milltown, 1909-10. Joyce described Conmee to Herbert Gorman as ‘a very decent sort of chap’. (See Fargnoli & Gillespie, James Joyce A to Z: An Enclyclopaedic Guide to his Life and Work, Bloomsbury 1995, p.43.

Note: His chance meeting with John Stanislaus Joyce resulted in James and Stanislaus [Jnr.] entering Belvedere as free students. Fr. Conmee also arranged that the Joyce boys would have breakfast before class in the college. The first allusion to him in Ulysses is in “Lotus Eaters” where Bloom thinks, “Conmee: Martin Cunningham knows him: distinguished looking. Sorry I didn’t work him about getting Molly into the choir" (U5.331. His first appearance is in the “Wandering Rocks” episode where his pious thoughts about Providence set at Charleville Mall are conveyed by means of a stylised interior monologue and and later on, he reflects on the Church’s foreign missions when he sees a black man on a tram. Fr. Conmee has read in the day’s newspapers about the tragic steamboat accident in New York which he views from a theological perspective as an occasion for a ‘perfect act of contrition’. He also sees Lenehan emerging from the shrubbery with a young woman and seems free of any suspicions. He is the object of Martin Cunningham’s attempts to get Patrick Dignam, the son of the deceased (and uninsured) character whose funeral is taking place on Bloomsday, into the Institute for Destitute Children in Fairview. In the “Oxen of the Sun” episode, the medical student Francis reminds Stephen Dedalus ‘of years before when they had been at school together in Conmee’s time” (U., 14.1110-11.). In the “Circe” episode, he pops out of the piano to berate Stephen Dedalus. [These notes assembled from various websites; 24.05.2014.]

Further: ‘Joyce wrote the “Wandering Rocks” with a map of Dublin before him on which were traced in red ink the paths of the Earl of Dudley and Father Conmee. He calculated to a minute the time necessary for his characters to cover a given distance of the city’ (Frank Budgen, James Joyce and the Making of Ulysses, 1934, &c.)

[ top ]

Charles Ghezzi: ‘The Italian priest who taught Joyce Italian at the Royal University was Fr. Charles Ghezzi, SJ. Joyce bestowed the name of Dr. Artifoni on him Stephen Hero [Cape Edn., pp.174-75] - a name that properly belonged to Almidano Artifoni, the owner of the Berlitz School for whom Joyce worked in Pola and Trieste. The Italian Jesuit is also to be met with under the name of Artifoni in Ulysses - notably in “Wandering Rocks” [U293] but also, with a single line, in “Circe” [U635]. In A Portrait of the Artist, Ghezzi appears under his own name in a shorter passage than the draft-novel - being now confined to an entry in Stephen’s diary at the close [AP253]

Fr. Ghezzi in Stephen Hero: ‘[Stephen] chose Italian as his optional subject, partly from a desire to read Dante seriously, and partly to escape the cruch of french and German lectures. No-one else in the college studied Italian and every second morning he came to the college at ten o’clock and went up to Father Artifoni’s bedroom. Father Artifoni was an intelligent little moro, who came from Bergamo, a town in Lombardy. [...] The Italian lessons often extended beyond the hour and much less grammar and literature was discussed than philosophy. The teacher probably knew the doubtful reputation of his pupil but for this very reason he adopted a language of ingenious piety, not that he was himself Jesuit enough to lack ingenuousness but that he was Italian enough to enjoy a game of belief and unbelief. He [174] reproved his pupil once for an admiring allusion to the author of The Triumphant Beast.

—You know, he said, the writer, Bruno, was a terrible heretic

—Yes, said Stephen, and he was terribly burned

But the teacher was a poor inquisitor. [...] He was unlike many of the citizens of the third Italy in his want of affection for the English and he was inclined to be lenient towards the audacities of his pupil, which, he supposed, must have been the outcome of too fervid Irishism. He was unable to associate audacity of thought with any temper but that of an irredentist.’ (Stephen Hero, Jonathan Cape Edn., p.174-75.)[Note: A moro (adj.) denotes a dark-haired man, with overtones of Moorish appearance. See Oxford Paravia Italian Dictionary.]

Fr. Ghezzi in A Portrait - diary entry for 24 March: ‘Other wrangle with little roundhead rogue’seye Ghezzi. This time about Bruno the Nolan. Began in Italian and ended in pidgin English. He said Bruno was a terrible heretic. I said he was terribly burned. He agreed to this with some sorrow. Then gave me a recipe for what he calls risotto alla bergamasca [...].’ (Corr. Edn., Jonathan Cape 1968, p.253.)

[See Don Gifford, Ulysses Annotated [2nd Edn.], California UP 1989, p.266; and see further under Notes > Giordano Bruno, supra.]

[ top ]

John Henry Alleyn, the Cork wine merchant who became a major share-holder in the Chapelizod Distillery which John Stanislaus Joyce engaged in, retired to Cork after the debacle in 1878 and later to Menton [Mentona], where he died and is buried. (See Peter Costello, James Joyce: The Years of Growth, 1992, p.46.)

Henry Blackwood Price, an Ulsterman whom Joyce met in Trieste, was the model for Mr. Deasy in Ulysses. Price pestered Joyce by letter constantly encouraging him to write to the papers about a cure for foot and mouth, known to him, which was then plaguing Ireland, leading to the destruction of 2000 cattle. Joyce remarked that Price should be looking for a cure for his wife’s foot and mouth disease, but ‘nevertheless surprised himself by writing a sub-editorial on the disease for The Freeman’s Journal.’ (See Maud Ellmann, ‘Ulysses: Changing into an Animal’, in Field Day Review, 2, 2006, p.p.81, citing Ellmann, James Joyce, p.326; Letters, Vol. 2, 300, and Joyce, ‘Politics and Cattle Disease’, 1913; in The Critical Writings, 1959, pp.238-41.)

James Fitzharris (“Skin-the-Goat”): b, 4 Oct. 1843, Ballybeg [var. Clonee], Co. Wexford; dismissed from his employment on the Sinnott estate for wrecking a fox hunt led by Lord Courtown; moved to Dublin; labourer and cab-driver; lived on Denzille St. opp. James Carey; nicknamed for killing a goat with a claspknife when he saw it eating straw from a horse’s collar (var. skinned it and sold skin to pay debts); sworn in to Irish National Invincibles by Carey, Dec. 1881; involved in attempts on life of W. E. Forster [Irish Sec. of State]; drove Carey and two others to Phoenix Park, 6 May 1882; afterwards carried three away from scene of the assassination of Cavendish and Burke; arrested at Lime St. home in Feb. 1883, on informer’s information; found not guilty of murder; abused Carey and Kavanagh, both turned Queen’s witnesses (“approvers”) in court; retried and found guilt of accesory to murder, 15 May 1883; servitude for life; Maud Gonne laid wreathe on his wife’s grave in Glasnevin when the latter died in 1898; released Aug 1899; travelled to America, but deported; attempted to launch stage career in Liverpool, but returned to Dublin; well-known Dublin character; d. 7 Sept. 1910, S. Dublin Union Infirmary; bur. with his wife; a plaque commemorates him and the Invincibles. (See RIA Dictionary of Irish Biography, 2009; entry by James Quinn and Liam O’Leary, rep. in The Irish Times, 6 Feb. 2010.) For a note on Forster, see under Charles Gavan Duffy, supra

See also Vivien Igoe, ‘Blazes Boylan, Skin-the-Goat and Frederick Sweny: the real people of Ulysses’, in The Irish Times (16 June 2016): James FitzHarris, known as Skin-the-Goat, was born on October 4th, 1833 at Co Wexford. From a family of evicted farmers, he was forced to seek employment in Dublin. He became a well-known Dublin jarvey or cab driver, and was described as coarsely cheerful and robust. He got the nickname from a goat he found plucking at the straw that filled a horse’s collar. He killed the goat, skinned it and used its hide to cover his knees while driving. Another story is that he sold the hide of his pet animal to pay for his drinking debts. / It was FitzHarris who drove the Invincibles to the Phoenix Park on May 6th, 1882 when Lord Frederick Cavendish, the chief secretary for Ireland, and Thomas Henry Burke, the under-secretary, were assassinated. It is not known whether FitzHarris was a member of the Invincibles but he was among a number of men arrested and put on trial. Five were sentenced and executed at Kilmainham Gaol. / FitzHarris was offered £10,000 by the British government, and transport to any foreign place of his choice, to inform on the men. He declined and - although not guilty of murder - was sentenced to penal servitude for his part in the affair. He later declared: “I came from Sliabh Buidhe where a crow never flew over the head of an informer.” He died in 1910 in the South Dublin Union Workhouse on James’s Street. A memorial plaque was unveiled by the National Graves Association on his grave in Glasnevin Cemetery on July 14th, 1968.) [Available online; accessed 16.06.2016; also review of Igoe’s The Real People of Joyce’s Ulysses: A Biographical Guide by Terence Killeen, in The Irish Times (11 June 2016) - online.]

[ top ]

George Clancy, Lord Mayor of Limerick (and Mat Davin in A Portrait), was assassinated by policemen [Black and Tans?] in Limerick during curfew hours on 5 May 1921, along with with his predecessor, Michael O’Callaghan, and another prominent nationalist, Joseph O’Donoghue. Clancy is the subject of a document enscribed ‘Discharge, temporary, from jail for ill health ... from Cork Mall Jail’, produced on 21 Nov 1917, and held in the Limerick City Museum where it is displayed in the online catalogue [link].

[ top ]

Michael Lennon: Though friendly with Joyce for some years, Judge Michael Lennon published an attack on him in Catholic World [CXXXII], March 1931, accusing Joyce of working for the British ‘department propaganda’ in Italy during the war and accepting ‘sufficient cash in hand to be able to loll about for several months’ in Paris afterwards while ‘the British government was carrying on a war [..] against the nationalist forces in Ireland which culminiated in the Easter Week rebellion’ (Catholic World, CXXXII, March 1931, pp.643, 648 [cited as pp.641-52 in Ellmann, James Joyce, 1959, 1965 Edn., p.655.]). The article served as an incentive for Joyce’s co-option of Herbert Gorman to write James Joyce, 1939 - though often Gorman strayed from Joyce’s own intentions. (John Whittier-Ferguson, ‘Embattled Indifference: Politics on the Galleys of Herbert Gorman’s James Joyce’, in Vincent J. Cheng, et. al., eds., Joycean Cultures/Culturing Joyces, Delaware UP 1998, pp.134-48. [See extract, infra.]

Note - a letter from Joyce to Michael Lennon is held in the Harley K. Croessmann Collection of Emory University Library (Irish Literary Collection). See catalogue details as follows: ‘In 1930 and 1931, Joyce wrote two letters to Michael Lennon, who had agreed to support Joyce’s campaign on behalf of John Sullivan. The letters indicate that Joyce was ingenuously grateful for Lennon’s help; and yet, interestingly enough, the second letter is dated in the same month as Lennon’s biographical manuscript about Joyce (also contained in the collection) that appeared in Catholic World in 1931. The article, which is filled with inaccuracies, came to Joyce’s attention years later and deeply offended him.’

Further: ‘Two manuscripts by Michael J. Lennon, including the one mentioned above, are collected here. The first, written and published in 1931, contains a highly imaginative account of Joyce’s life and works considered by Joyce to be libelous. A few years later when Joyce was reviewing the manuscripts for the Gorman biography, he asked the author to remove an entire section which erroneously, Joyce maintained, depicted his relationship with his father. Joyce felt that the passage sounded as if it had been inspired by Lennon’s fabricated essay. Joyce had only become aware of the existence of Lennon’s article several years after it was published, and he considered it a disservice that his friends had not brought it to his attention earlier. In fact, Joyce blamed his lack of success on the other side of the Atlantic largely on this very matter - the fact that the article had been published without challenge in America. Gorman had, it turns out, surreptitiously enlisted the help of Lennon when he was researching the biography; but, well aware of Joyce’s disposition, Gorman left Lennon’s name off his list of acknowledgments when the book was published. The other Lennon manuscript in the collection was written in the mid 50’s and identifies the historical counterpart of John F. Taylor who delivers an oratory in Ulysses.’ (See Irish Literary Collection Portal, Emory University > Croessmann catalogue - online.)

Note: Joyce wrote to Curran in August 1937 indicating that he would not take the chance of returning to Ireland and that the map of his countrymen was legibly marked Hic sunt Lennones - a reference to Michael Lennon and a pun on hic sunt leones (lions), the tag of the medieval map-makers.

[ top ]

Alfred Bergan: Bergan is called a practical joker by Gifford (Annotations to Ulysses, 1984); he was a solicitor’s clerk for David Charles, Clare St., Dublin; and later assistant to the sub-sheriff of Dublin John Clancy, in 1904, with a home on Clonliffe Rd.; see Joyce’s letter of 14 Oct. 1921 in Letters, Vol. 1, 1957, p.174. Richard Ellmann (James Joyce, OUP 1957) calls him a frequent visitor to John S. Joyce’s at 1 Martello Tower, Bray, and later asst. to the sub-sheriff of Dublin. In 1934 Joyce wrote to him: “We used to have merry evenings in our house, used we not?” (Ellmann, op. cit., p.23.) Clancy was a neighbour of the Joyces on N. Richmond St. and appears thinly disguised in Ulysses as Long John Fanning and under his own name in Finnegans Wake. Bergan, his assistant, delighted the Joyces by telling them how on one of those occasions when a criminal had to be hanged, Clancy betook himself to London and left the arrangements to Bergan who advertised for a hangman and received the information that Joyce used to adorn the “Cyclops” chapter of Ulysses, changing the name of the information from Billington to Rumboldt to pay off a score in Zurich. (Ellmann, op. cit., pp.43-44.) Leopold Bloom’s remarks on seagulls in Ulysses were originally addressed by Joyce to Bergan during a walk from Fairview to Dollymount and back. (See Niall Sheridan’s interview with Bergan; Ellmann, op. cit., p.45.) On one occasion, JAJ stopped Bergan in the street and asked him to sing “McSorley’s Twins”, which he committed immediately to heart and sang that night at the Sheehys’. (ibid., p.52.) Bergan recalls JSJ nodding tragically at the portraits being carried out to Mrs McGuinness’s, the pawnbroker, with the remark: ‘there goes the whole seed, breed and generation of the Joyce family’. JSJ managed to scrape together enough to redeem them. (Ibid., p.71.) Bergan is the author of the story of JSJ and the Dollymount tram which he tells in an interview with Niall Sheridan [q.v ] (Ellmann, op. cit., p.109-10.n.) After the death of Joyce’s father, he asked Bergan to take charge of setting up a monument for him, resulting in his gravestone being erected with an inscription by Joyce that includes the name of his mother in keeping with Bergan’s information that JSJ expressed the wish for her name to be added ‘in the curious roundabout delicate and allusive way he had in spite of all his loud elaborate curses’, acc. to Joyce in a letter to Harriet Weaver of 22 July 1932 (Ellmann, op. cit., p.657.) Joyce wrote a lengthy letter to Bergan (25 May 1935) on hearing of the death of Tom Devin - a frequent visitor at Martello Tce., and a singer and piano-player there; Devin, who Joyce variously spells thus and Devan, is Mr. Power in Dubliners and Ulysses, as his letter makes clear. (Ellmann, op. cit., pp.717-18.)

See also the letter to Alf Bergan of 25 May 1937 (MS NY Public Library) in which Joyce dwells on ‘the pleasant nights we used to have singing’ in his father’s house and recalls the laughter induced in Tom Devin by ‘certain sallies of my father.’ [SL384]: ‘The Lord knows whether you will be able to pick the Kersse-McCann story out of my crazy tale. It was a great story of my fathers [sic] and I’m sure if they get a copy of transition in the shades his comment will be “Well, he can’t tell that story as i used to and that’s one sure five!”’. See also note: Thomas Devin (d.1936) was the model for Mr. Power in Dubliners and Ulysses.

Hugh Kennedy: who defeated Joyce for Chair of the L&H, was successfully elected in the Dublin South bye-election of 1923 - defeating Michael O’Mullane, who was supported by Countess Markievicz - as show in a letter sent to the Mountjoy Sinn Fein Club and signed her appealing for volunteers to help with O’Mullane’s campaign for Sinn Fein. (See Whyte’s Irish Art - website [asp]; accessed 07.03.2017.)

[ top ]

Vladimir Dixon: Dixon, the author of a letter written in the form of a humorous pastiche of Wakese sent to Joyce care of Sylvia Beach was included in Our Exagmination Round His Factification for an Incamination of Work in Progress (Paris: Shakespeare & Co. 1929). Beach assumed that Dixon was none other than Joyce himself (a supposition shared by Stuart Gilbert and Richard Ellmann) but in fact he was a real person - born in Russia in 1900, grad. in mechanical engineering (BSc., MIT), 1921; settled in Paris, 1923; published poetry and essays; d. Dec. 1929 - without ever having met Joyce. (See Sam Slote, Catalogue Notes, Buffalo Univ. Library “Bloomsday” Centennial Exhibit, 2004 [Available online - Index > Case XI; accessed 31.12.2008 & 13.04.2017]

Vladimir Nabokov: Nabokov’s marginalia to Joyce’s Ulysses are preserved in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library [NYPL]. (See Nicholas Allen, ‘A Turn-up for the Book in New York’ [“A Scholar’s Summer”], Irish Times (8 Aug. 2009), Weekend, p.11.)

John Eglinton, in dialogue with Yeats in the Daily Express (1899), anticipates an argument later used by Stephen Dedalus about art confronting rather than escaping reality. Eglinton wrote: The poet ‘who looks too much away from himself and his age does not feel the facts of life enough, but seeks in art an escape from them.’ (Eglinton, W B. Yeats, AE & William Larminie, Literary Ideals in Ireland (Dublin: Daily Express; London: Unwin 1899; quoted in Stephen Watt, Joyce, O’Casey, and the Irish Popular Theater (Syracuse 1991). Note that this text is quoted substantially by Louis MacNeice in his Poetry of W. B. Yeats. [13 and ftn.] while the dialogue is also cited in Cairns & Richards, Writing Ireland, 1988, pp. 66, 120.)

Monk Gibbon: Mademoiselle, a character in Gibbon’s Mount Ida (1948), says: ‘You know, Ulysses would have been a failure in England. No Englishman ever prided himself on being adroit. Get that into your head. They have only one virtue - straightness. Cultivate it, or you will do nothing with them.’

Chenevix-Trench: Samuel Chenevix Trench adopted the first-name Dermot (aka ‘Diarmuid Trench’) and played the tramp in Hyde’s Casadh an tSugain. He is Haines in the “Telemachus” episode of Ulysses - and later (unrelatedly) committed suicide. The family name was besmirched in posthumous revelations about the Eton headmast Anthony Chenevix-Trench, formerly headmaster of Shrewsbury public school, who was a flagellomaniac. According to Nick Frazer, “He would offer his culprit an alternative: four strokes with the cane, which hurt; or six with the strap, with trousers down, which didn ‘t. Sensible boys always chose the strap, despite the humiliation, and Trench, quite unable to control his glee, led the way to an upstairs room, which he locked, before hauling down the miscreant’s trousers, lying him face down on a couch and lashing out with a belt.” After Eton he ruled at Fettes. (See John Carey, review of Nick Frazer, The Importance of Being Eton, in The Sunday Times, 4 June 2006; reported at Anngirfan blogspot - online; accessed 14.03.2017.)

[ top ]

Albert Altman (1851-1903; aka “Altman the Saltman”): A case for Albert Liebes Lascar Altman to be considered as part-model for the fictional Leopold Bloom in Ulysses has been made by Vincent Altman O’Connor, the grand-son of Emmanuel Altman (1889-1963) who was Albert’s nephew. Altman was a Jewish salt merchant and member of Dublin Corporation in 1903; he gained many enemies by revealing non-payment of rates; Altman lived at 11 Usher’s Island; his brother Mendal (1866-1915) shared a house with Joe Hynes who appears in “Ivy Day in the Committee Rooms” and also in Ulysses; Albert’s daughter “Mimi” was a singer with whom Joyce was once smitten, according to Altman family tradition; she sang at Sandymount Church where Joyce was invited to become tenor; Mendal’s daughters, were Cissy and Edy - names employed by Joyce for the Caffrey and Boardman sisters in “Nausicaa”; Altman was an “advanced” Irish nationalist and a temperance enthusiast - an interest shared with Paddy Dignam, the drunkard in Ulysses; Altman’s father Moritz died after ingesting poison - as Bloom’s father does in the novel; when Albert died in 1903 he was living in Ballsbridge and hence his funeral route would have been almost the same as Dignam’s, departing from Sandymount; he is buried in Glasnevin some metres from Matthew Kane, the model for Dignam; with him are buried his wife Susan, their daughter Mimi, and a son Bertie who died in infancy - a family unit to be compared with Bloom, Molly, Milly and Rudi. Vincent Altman O’Connor notes that the Irish writer John D. Sheridan, a conservative Catholic, urged Emmanuel Altman to read Ulysses and take legal advice following a successful suit of the BBC by Reuben J. Dodd after the novel was broadcast by the station in the 1960s; Emmanuel had no interest in so doing so, nor in Joyce’s ‘smutty book’.

Notes: Altman died of diabetes shortly before the question of ‘at least eleven’ Borough members failure to pay their rates raised by him has reached its conclusion. No foul play was suspected. He was buried in Glasnevin and was dead before Bloomsday and hence, as Altman O’Connor points out, the funeral party which buries Dignam must have passed his grave. Altman the Saltman was cited in the trial of the Invincibles following the Phoenix Park Murders since it emerged that his yard had been the intended scene of the assassination of William Edward Forster - Lord Cavendish’s predecessor as Chief Secretary for Ireland. Albert Altman was succeeded in the Usher’s Quay ward by his brother Mendal in 1907. Altman was occasionally known as the Jewish Fenian - a name coined by Barrow Belisha, the Liverpool MP [best known for sponsoring Belish beacons or traffic lights in Parliament; vide. FW267: ‘Belisha beacon, beckon bright! Usherette, unmesh us!’.] (Derived from the above: BS - 24.08.2017.)

[ See Neil R. Davison, An Irish-Jewish Politician, Joyce’s Dublin and Ulysses: The Life and Times of Albert L. Altman Florida UP 2022), 294pp. Details: In this book, Neil Davison argues that Albert Altman (1853?1903), a Dublin-based businessman and Irish nationalist, influenced James Joyce’s creation of the character of Leopold Bloom, as well as Ulysses’s broader themes surrounding race, nationalism, and empire. Using extensive archival research, Davison reveals parallels between the lives of Altman and Bloom, including how the experience of double marginalization - which Altman felt as both a Jew in Ireland and an Irishman in the British Empire - is a major idea explored in Joyce’s work. (Extract from Florida UP notice - online; accessed 20.01.2023.]

The following add. links have been supplied by Vincent Altman O’Connor: Frank McNally, An Irishman’s Diary, in The Irish Times - online (18 May 2017); Vincent Altman O’Connor at the James Joyce Centre (Lect. of 8 May 2017) - online; abridged version of same in History Ireland (May-June 2017) - online; Vincent Altman O’Connor on the RTÉ History Show (Aug. 2017) -online; Vincent Altman O’Connor, with Neil R. Davison [Oregon US] & Yvonne Altman O’Connor [curator at the Irish-Jewish Museum], ‘Altman the Saltman and Joyce’s Dublin: New Research on Irish-Jewish Influences in Ulysses’, in Dublin James Joyce Journal online; Neil R. Davison, a lecture at The Irish-Jewish Museum - online; Shane MacThomais, in Comeheretome: Dublin Life and Culture - online; Colum Kenny in the Journal of Modern Jewish Studies - online; Neil R. Davison, “Ivy Day”: Dublin Municipal Politics and Joyce’ in Journal of Modern Literature, 42: 4 [ Joyce, Beckett, Coetzee] ([Indiana UP] Summer 2019), pp.20-38. O’Connor also notes that Joe Duffy cites “Altman the Saltman” in Children of the Rising: The untold story of the young lives lost during Easter 1916 (Hachtte 2015)

Joseph O’Connor, ed., Yeats is Dead! (Cape 2001), a collaborative novel by Roddy Doyle, Conor McPherson, Gene Kerrigan, Gina Moxley, Marian Keyes, Anthony Cronin, Owen O’Neill, Donal Kelly, Gerard Stembridge and Frank McCourt. The basics of the plot concern a pharmeuticals rep. called Tommy Reynolds, murder[ed] in a mobile home after a visit by heavies in the shape of off-duty gardaí Nestor and Roberts, apparently working for a crime-world figure Mrs Bloom; novel littered with Joyce allusions and characters of Joycean pedigree incl. Eveline, Molly Ievers [Ivors], O’Madden Burke, Dignam and even Kinch. Issued with profits to Amnesty on its 4th Anniversary. (Noticed by C. L. Dallat, in Times Literary Supplement [Irish issue], 29 June 2001, p.22.)

[ top ]

International Figures

| The letter that changed literary history .. | ||

|

Ezra Pound (2) - the EP-JJ Correspondence: 198 letters passed between Pound and Joyce of which 103 from Joyce of which 26 have been published by 1995) and 95 from Pound to Joyce of which 75 have been published - chiefly in Forrest Read, letters of EP to JJ. (See Robert Spoo, ‘Unpublished Letters of Ezra Pound to James, Nora, and Stanislaus Joyce’, in James Joyce Quarterly, 32, 3/4 (Spring-Summer 1995), pp.533-581; available at JSTOR - online

[ top ]

John Quinn: Quinn sold his collection of Joyce’s manuscripts when terminally ill with cancer. In its place he purchased a set of letters by George Meredith, much to Joyce’s indignation. Quinn’s collection of Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, Van Gogh, Seurat, et al., sold by his heirs for ludicrously low prices. (See further under John Quinn > Richard Ellmann - supra.)

[ top ]

Sylvia Beach (1): b. Nancy Woodbridge Beach (14 March, 1887-5 Oct. 1962) [nb. Oct. 6 in Letters, ed. Keri Walsh], the daughter of Sylvester Beach, a prominent Presbyterian minister from Princeton, NJ, and Eleanor Thomazine [née] Orbison - after whose mother she was called Nancy (being an Indian missionary with her husband); lived in young the family lived in Baltimore (Maryland) and in Bridgeton (NJ); moved to France with her family to France when her father was app. minister to the American Church in Paris, and director of the American student centre, 1901; remained there for three years (1902-05), returning to America when her father became minister of the First Presbyterian Church of Princeton, 1906; lived two years in Spain; worked for Balkan Commission of the Red Cross during WWI; returned to Paris to study French literature, 1916; at Bibl. Nationale she met Adrienne Monnier, prop. of La Maison des Amis des Livres (a lending bookshop - otherwise ‘librairie/société de lecture’ - fnd. 1915) - who counted Gide, Paul Valéry and Jules Romains among her friends - and became her lover, remaining close friends till the latter’s death by suicide in 1955 [suffering acturely from tinnitus symptoms taken to be Ménièsere’s Disease - causing Beach to write, ‘I’m glad it’s over’]; initially planned to open branch of Monnier’s firm in New York but constrained by finances and established Shakespeare and Company at 8 rue Dupuytren, 19 Nov. 1919; met Joyce at a party given by André Spire on 11 July 1920 - which Monnier also attended. moved to 12 rue de l’Odéon where she occupied premises opposite Monnier - who had also been at the Spire’s party - at 7 rue de l’Odéon, May 1921 [recte; var. by autumn 1921: Ellmann]; visited by Joyce at both premises; offered, and then formally agreed to publish Ulysses on 25 March 1921, and ultimately did so on 2 Feb. 1923; Shakespeare and Company supported during the Depression by wealthy friends including Bryher [nom de plume of Annie Winifred Ellerman; marriage of convenience to Robert McAlmon]; at Gide’s advice, she created the Friends of Shakespeare and Company with an annual subscription of 200 francs a year for literary readings, 1936; interned for six months after Occupation of Paris [recte as alien] - purportedly on refusing to sell Finnegans Wake to a German officer; hideher stock in an unoccupied apartment above 12 rue de l’Odeon, 1941; Shakespeare and Company was ‘liberated’ after the war by Ernest Hemingway, 1944 [var. 1946]; did not reopen the shop; lived on modestly in Paris; received honorary degree from Univ. of Buffalo, 1959; d. Île de France, 1[6 Oct.] 962; gave an interview to RTE in that year [with Niall Sheridan for Hilton Edwards, Self-Portraits ser.; broadcast 2 or 3 Oct. 1962); [cremated in Paris;] remains buried in Princeton Cemetery; George Whitman received her permission to use the name of her shop, which he did in 1964 - setting up his establishment at rue de la Bûcherie on the Left Bank (V arr.)

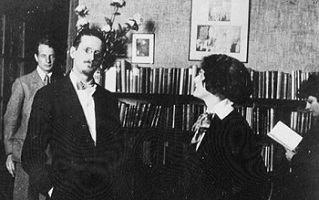

Holly Beach: a sister - was with her in the Balkans and visited in Paris; recipient of announcement about the forthcoming publication of Ulysses (23 April 1921: “It’s going to be in October”) an letters anticipating her arrival in Paris in November (with regrets that it would be so late); thought to be in the photograph with Beach and John Rodkers [or Cyprian?] in Shakespeare and Company, probably at the rue Dupuytren premises - ergo circa Nov.-December 1921. Holly married Frederick Dennis, a Connecticut businessman, who donated his papers to the Princeton Library incl. photos of the Beach children when young. His son Fred, Sylvia’s nephew, inherited the rights to her papers and is thanked accordingly in Jeri Walsh’s edition of the Letters.

Cyprian Beach: Note that Cyrian is called a ‘sister’ in Walsh, ed., Letters (2010), Introduction, p.xvii - while the following entry is given in the Chronology: ‘All three sisters, Syvlia, Holly and Cyprian are living in Europe.’ (p.xxx.) Cyprian - whose given name was Eleanor and is often so referred to in the actual Letters hoped to be an actress. She died in 1951 (idem., p.9; p.xxxiii.)

[ top ]

| Turismo Letterario > Paris > Shakespeare and Company | ||

|

||

| [Note: The website illustrates the interior of Shakespeare and Company with the familiar photograph of Joyce and Beach standing beside her desk with a third figure in the background usually taken to be John Rodker but here identified as Cyprian Beach (d.1951), the brother of the bookshop owner [libraia]. Cropped from the picture is the female figure browsing at the bookshelves to the right who is identified elsewhere as Holly Beach, an identification which makes that of Cyprian - known of course to be her brother - a great deal more likely. The date is not given and the picture is reversed, thus placing Holly Beach on the left in comparison with the usual printings. | ||

|

||

| See Turismo Litterario - online; accessed 17 April 2017 [paras altered: BS.] | ||

|

[ top ]

Ulysses: In 1922 she published Ulysses using the Dijon de luxe [hand-setting] printer Darantière in 1,000 copies under the imprint of Shakespeare and Company [rather than his own]. Her reprints of Ulysses ran through seven printings in the first edition and four more in the second, ending with the 11th printing in 1930. Shakespeare and Company continued to trade until the German Occupation of Paris in 1940 and was ‘liberated’ by Hemingway - according to himself - in 1946. Joyce and Beach had a rocky after-life since he forced her to relinquish her world rights to Ulysses in December 1930, while in 1935 she sold the MS of Stephen Hero, which he had given her ingratitude (calling it the original MS of A Portrait)- to NY State University (Buffalo) causing trouble for the writer. It remains uncertain whether he ever intended it to be read at all but he seems to have responded boldly to news of its capitivity in his final revision of the “Shem” chapter of Finnegans Wake which revisit some of the episodes and ideas compassed in that ambitous - if ultimately futile - exercise in egoistical authorship. [BS]

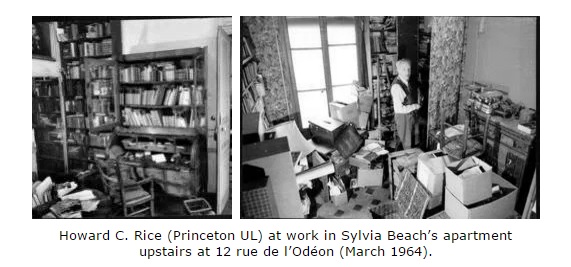

Stephen Hero: The Joyce papers in her possession, being gifts from Joyce, were auctioned at La Hune and largely acquired by SUNY (Buffalo) for the Lockwood Mem. Library with funds supplied by Constance and Walter F. Stafford, who received from Beach a copy of Ulysses in her possession (1st Edn., No.80). See Sam Slote, Catalogue Notes, SUNY Library (Buffalo) “Bloomsday” Centennial Exhibit, 2004 [online; 31.12.2008]. The Staffords returned to the fray to assist with the purchase of the residuence [relict] of Beach’s collection preserved in her apartment over Shakespeare and Company in 1964. (See Howard C. Rice - in “Shakespeare and Company” [appendix], as attached.)

Shakespeare & Co. In 1951 the American George Whitman opened an English-language bookshop called Le Mistral at 37 Rue de la Bûcherie (nr. Pont St. Michel) which became a haunt of young American writers - and, in 1964, two years after the Beach’s death, he changed its name to Shakespeare & Co., in her honour as the doyen of literary American expatriates and apparently with her permission. The business has been carried on by a daughter called Sylvia Beach Whitman who organises a literary festival there besides maintaining a steady trade in English-language books. Opinions about its authenticity in relation to the literary ‘scene’ of the 1920s and 30s must inevitably vary but it certainly merits its place on the tourist map for young people today.

See further .. Gallery of photographs with Joyce at Shakespeare and Company - as attached Skeleton bibliography in “Shakespeare and Company” > Appendix - as attached

Sylvia Beach (3): In 1924, Sylvia Beach arranged a recording of Joyce reading from Ulysses - a ‘declamatory’ passage from “Aeolus” at his insistence - in 1924. The technician from His Master’s Voice in Paris who assisted her was called Coppola. Later she organised another made by Ogden Nash and the BBC in London. Joyce and Beach had a rocky after-life since he forced her to relinquish her world rights to Ulysses (which she famously published) in Dec. 1930, and in 1935 she sold the MS of Stephen Hero, which he had given her, to the State University of New York (SUNY) at Buffalo causing trouble for the writer. It remains uncertain whether he ever intended it to be read but he seems to have responded boldly to news of its captivity in his final revision of the “Shem the Penman” episode of Finnegans Wake. Arguably, too, the addition of ‘panepiphanal’ to a late revision of “Balkelly” episode [613] - answering to ‘epiphany’ in Stephen Hero - derives from this cause.

RTE Interview: Beach was interviewed by RTE’s Self-Portrait series in 1962 - in the course of which she says: “[...His ‘buke’ as he pronounced it would never come out and so he sat there with his head in hands and I said to him: ‘Would you like me to publish Ulysses?’ And he said, ‘I would’. He seemed very much relieved.” [See details at Broadsheet.ie - online; accessed 19.06.2014. See Youtube video - online - or see copy under Shakespeare and Company - infra.]

Sylvia Beach (4) - Steve King, ‘Joyce, Fitzgerald, Jumping’, at Today in Literature (2014): ‘On this day [27 June 1928], Sylvia Beach hosted a dinner party in order that F. Scott Fitzgerald, who “worshipped James Joyce, but was afraid to approach him,” might do so. In her Shakespeare and Company memoir Beach delicately avoids describing what happened, although she perhaps suggests an explanation: “Poor Scott was earning so much from his books that he and Zelda had to drink a great deal of champagne in Montmartre in an effort to get rid of it.” According to Herbert Gorman, another guest and Joyce’s first biographer, Fitzgerald sank down on one knee before Joyce, kissed his hand, and declared: “How does it feel to be a great genius, Sir? I am so excited at seeing you, Sir, that I could weep.” As the evening progressed, Fitzgerald “enlarged upon Nora Joyce’s beauty, and, finally, darted through an open window to the stone balcony outside, jumped on to the eighteen-inch-wide parapet and threatened to fling himself to the cobbled thoroughfare below unless Nora declared that she loved him.“ [...] Several years later, Joyce’s daughter, Lucia would have the same psychiatrist as Zelda, stay for a time in the same Lake Geneva clinic, and also be diagnosed as schizophrenic.’ (Available online - online; accessed 29.06.2014.)

Bibl. Noel Riley Fitch, Sylvia Beach and the Lost Generation: A History of Literary Paris in the 1920s and 1930s (NY: Norton; London: Penguin 1985). Note that Fitch characterises Sylvia Beach as ‘heir to nine ecclesiastical generations’ (p.14; available online; accessed 13..04.2017.)

[ top ]

Sylvia Beach (5) - publishing Ulysses: When Ben Huebsch formally declined to publish Ulysses and John Quinn similarly failed to persuade Boni and Liveright to do so, Joyce went round to Shakespeare and Company to bemoan his disappoint. Beach then said: ‘Would you let Shakespeare & Co. have the honour of bringing out your Ulysses?’ - with the aid of Adrienne Monnier in spite of her total ‘lack of capital, experience, and all the other requisites of a publisher’. An agreement was signed on or around 10 April 1921 to produce an edition of 1,000 (100 copies on Holland paper, to be signed by author and to be sold at 350 frs.; 150 copies on vergé d’arche to be sold at 250 frs., and 750 copies on linen to be sold at 150 frs. each all to be printed by Maurice Darantière of Dijon (proposed by Monnier) - with 66% royalties to author. On hearing of the plan, Harriet Shaw Weaver lent immediate support, collating the names of all those interested in the novel, and advancing £200 to Joyce on royalties for an English edition which she would publish from the French sheets under the Egoist Press imprint after the limited French edition had sold out. (See Richard Ellmann, James Joyce [rev. edn.] Oxford 1982, pp.504-05.)

See also Ellmann’s account of the first row with Beach, arising from Joyce’s request for that a third printing of Ulysses after the second printing quickly sold out and her rejection of the idea having been warned that the nigh-identical appearance of the second printing of Jan. 1923 might be taken as an attempt to issue ‘a bogus first edition’. (Ellmann, op. cit., 1982, pp.541-42.)

Joyce wrote of the dispute to Miss Weaver: ‘Possibly the fault is partly mine. I, my eye, my needs and my troublesome book are always there. There is no feast or celebration or meeting of shareholders but at the fatal hour I appear at the door in dubious habiliments, with impedimenta of baggage, a mute expectant family, a patch over one eye howling dismally for aid.’ (Letter of 17 Nov. 1922; Letters, Vol. 1, p.194; Ellmann, James Joyce [rev. edn.] 1982, p.542

Loss & Gain: ‘Ulysses was the paying investment of his lifetime after years of penury, Sylvia said, while hardly acknowledging the fact that the publishing costs almost wiped out her Shakespeare and Company. The peak of his prosperity came in 1932 with the news of his sale of the book to Random House in New York for a forty-five-thousand-dollar advance, which, she confessed, he failed to announce to her and of which, as was later known, he never even offered her a penny. “I understood from the first that, working with or for Mr. Joyce, the pleasure was mine - an infinite pleasure: the profits were for him.”’ (Janet Flanner, Paris was Yesterday 1925-39; quoted in Macy Halford, ‘Books and Their Makers: James Joyce and Sylvia Beach’, New Yorker [Blog], 5 March 2010 - online.)

—Janet Flanner, Paris was Yesterday 1925-39; (NY: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich 1988), p.[xi]

[ top ]

| The dispersal of Sylvia Beach’s books (Princeton Univ. Library 2011) |

When Sylvia Beach died in 1962, relict in her apartment were books, business papers, correspondence, photographs, paintings, and literary memorabilia. By agreement with her sister, Holly Beach Dennis, Princeton purchased these effects in early 1964. Associate librarian for special collections, Howard C. Rice arrived in Paris in late March and spent three weeks in the rooms over her famous bookshop, Shakespeare and Company, 12, rue de l’Oléon [sic for l’Odéon] Even though Sylvia Beach had given away 5,000 books to the American Library in Paris in 1951 (New York Herald Tribune, April 25, 1951) and even though she had sold her ‘Joyce Collection’ (as she called it) to the University of Buffalo in 1959, the apartment held, counting just the books, according to her sister’s lawyer, Richard Ader, 8,000 to 10,000 volumes. Untold numbers of papers and other objects filled closets, shelves, and walls. Howard Rice described as a ‘struggle’ his efforts to sort, collocate, organize, pack, and arrange shipping or further disposition of the apartment’s contents. When Rice returned to Princeton in April, he had completed dividing the contents as follows:

Coda I: In the late 1950s, Sylvia Beach prepared a 53 page list headed “The Library of Shakespeare and Company / Sylvia Beach / Paris - VI” together with a one page list of “Memorabilia from the Shakespeare and Company Bookshop, 12, Rue de l’Odéon - Paris -VI” Plans for making this list are mentioned in Sylvia Beach’s letter to Jackson Mathews, dated 2 July 1959. (Letters of Sylvia Beach, ed. K. Walsh [2010], p. 284). A copy of the list is in the Noël Riley Fitch Papers (C0841, box 3, folder 10). Coda II: Photographs from Howard Rice’s memoranda in C0108, box 276 |

|

| See online; accessed 14.04.2017 |

| Adrienne Monnier Archives - at IMEC - l’Abbaye d’Ardenne |

| La Maison des Amis des Livres, ‘société de lecture’, fut fondée en 1915, rue de l’Odéon à Paris, par Adrienne Monnier (1892-1955). Son objectif ‘tendait plutôt à représenter jusque dans ses manifestations les plus audacieuses, la Littérature moderne’, en réunissant ‘pour une Société de lettrés tous les avantages d’une bibliothèque et d’une librairie’. Adrienne Monnier organisa de nombreuses séances de lecture et sa librairie devint très vite le lieu de rencontre de toute l’avant-garde littéraire. Première éditrice, en 1929, de la traduction française d’Ulysse de James Joyce, elle publia - de 1916 à 1940 - vingt-six ouvrages, anima deux revues littéraires, Le Navire d’argent et La Gazette des Amis des livres, et en diffusa de nombreuses autres. Ces archives ont été déposées par Maurice Imbert, qui les avait lui-même reçues de Maurice Saillet, dernier collaborateur d’Adrienne Monnier. Depuis le premier versement, certaines pièces ont été extraites du fonds par le déposant, qui a également procédé à plusieurs accroissements du fonds. Fonds déposé par Maurice Saillet en 1997 |

| See IMEC [l’Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine] > Adrienne Monnier - online |

Syvlia Beach [6] - pay-back: Katherine Hughes, review of Letters of Sylvia Beach, ed. Keri Walsh, in The Guardian (31 July 2010): ‘[...] That Beach often felt a whole lot wilder underneath her chipper surface is suggested not just by her constant tension headaches but also by a remarkable unsent letter that she wrote to James Joyce in 1927 which is included in an appendix. It is the kind of letter we have all written, and then stuffed in a drawer for second thoughts. Addressing it to “Dear Mr Joyce”, Beach explains tautly that “as my affection and admiration for you are unlimited, so is the work you pile on my shoulders”, before proceeding to that lament which we would all love to scream to the world: “I am poor and tired too”. Shortly after not receiving this letter, Joyce shifted the focus of his emotional and financial needs on to another well-bred woman, this time the British Harriet Weaver, whom he proceeded to suck dry in much the same way.’

Sylvia Beach [7] - Ernest Hemingway wrote: ‘No one that I ever knew, was nicer to me. There was no reason for her to trust me. She did not know me and the address I had given her 74 rue du Cardinal Lemoine, could not have been a poorer one. But she was delightful and charming and welcoming and behind her, as high as the wall and stretching out into he back room which gave unto the inner court of the building, were shelves and shelves of the wealth of the library.’(A Moveable Feast, pp.35-36; posted by Moïcani Odéon on James Joyce Facebook pages, 19 July 2018.)

[See also RICORSO Library > Gallery > James Joyce > People > Sylvia Beach > Shakespeare and Company -as attached.]

[ top ]

Stuart Gilbert: b. 25 Oct. 1883, Chipping Ongar, Essex; son of Arthur Stronge Gilbert (Army officer, ret.) and his wife Melvina Kundiher Singh; grad. Cheltenham School and Hertford College, Oxford; joined Indian Civil Service, 1907; served inFirst World War; afterwards appointed to a judge on the Court of Assizes in Burma; ret. 1924; moved to Paris, 1925, with French-born wife Marie Agnès Mathilde Douin [“Moune”); translated works of Saint-Exupéry, Malraux, Camus, Sartre, Simenon, Cocteau, and other contemporary French authors into English; met Sylvia Beach [in 1924] and notified her of errors in French trans. of Ulysses; advised Joyce on the translation; remained on clise terms with Joyce up to his death in 1941; issued James Joyce’s Ulysses: A Study (1930), and later edited the first volume of Joyce’s Letters for Faber & Viking (1957); settled in Wales for the duration of WWII. Returned to Paris after the war, and died in his apartment at 7 rue Jean du Bellay on January 5, 1969

|

|

||

|

||

Harry Ransom Centre / University of Texas - online; accessed 18.08.2019 |

||

[ top ]

John Rodker (1894-1955)- He was the son of a Jewish corset-maker who fled form Poland during the pogroms of the 1880s and set up in Manchester, later moving to London. John Rodker was associated with the Whitechapel Boys [group] and was painted by co-member David Bomberg. He published modernist poetry (Adolphe, 1920) and contributed to The Dial (May 1914), including an essay on Bomberg. who designed a semi-abstract cover for his first collection in 1914 - based on studies of Rodker’s girlfriend Sonia Cohen performing as a member of Margaret Morris’s famous dance troupe. During the First World War he took the stance of a conscientious objector and sheltered with the poet R. C. Trevelyan until captured and imprisoned in Home Office Work Centre (formerly Dartmoor Prison). He recounted the experience in a later account called Memoirs of Other Fronts (anon. 1932). In the 1920s he was associated with Syvlia Beach’s Shakespeare and Company in Paris and was photographed there with Joyce in 1921. He co-published the 2nd edition of Ulysses with Harriet Weaver’s the Egoist Press (London) and founded his own company as the short-lived Ovid Press (1919) which published T. S. Eliot, Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound. (See Ben Uri Gallery - online; accessed 22.07.2017.)

|

|