Life

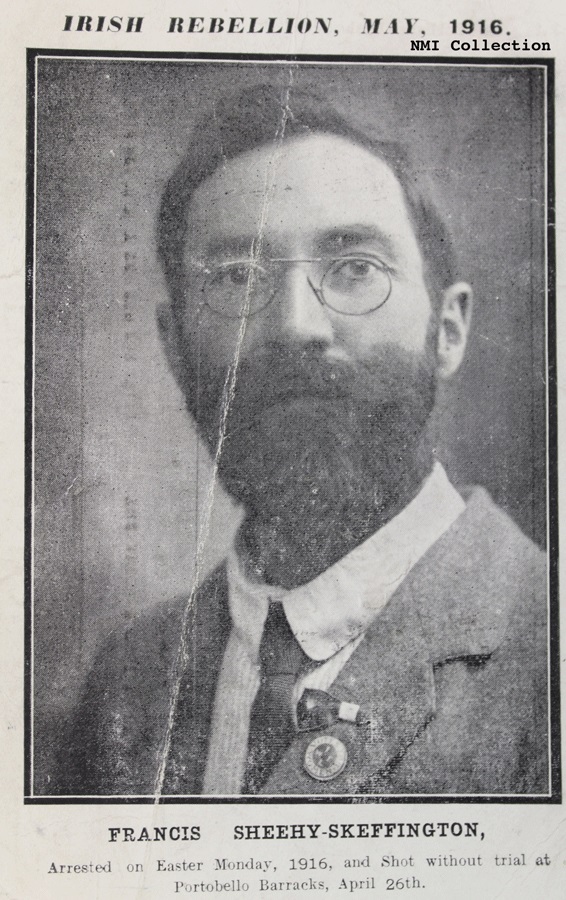

| 1878-1916 [given-name Skeffington; fam. “Frank”; prop. without hyphen; Sheehy-Skeffington in some title-pages - e.g., Michael Davitt, 1908]; b. 23 Dec., 1878, Bailieborough, Co. Cavan, son of Dr. Joseph Skeffington, an inspector of schools; ed. locally and UCD; elected first auditor of L & H, 1897; led Catholic students’s objections to W. B. Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen, 8-10 May 1899; issued “A Forgotten Aspect of the University Question” - pamphlet, jointly with another by James Joyce (Dublin 1901); taught at Kilkenny College and shared rooms with Thomas MacDonagh, next teaching at St. Kieran’s, 1902; appt. registrar at UCD, 1902-04; resigned after dispute over rights of women; m. Hanna Sheehy (q.v.; thereafter Sheehy-Skeffington), a dg. the Nationalist MP David Sheehy, 1903; wrote in support of objectors to Yeats’s Cathleen Ni Houlihan; issued Michael Davitt: Revolutionary, Agitator and Labour Leader (1908) - ‘a primer of Davitt’; served as a member of the Peace Committee during Dubin Lock-Out Strike, 1913; initially supported Home Rule and later criticised Redmond’s wartime policy; demonstrated against proposed military conscription, and was arrested and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour; |

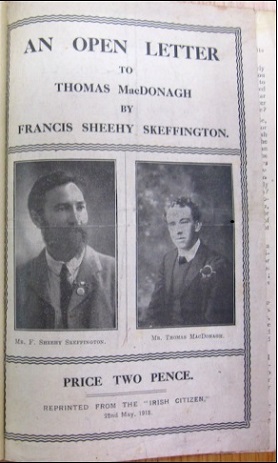

| went on hunger-strike; released with support of George Bernard Shaw, Robert Lynd, and Conal O’Riordan in English newspapers; ; issued a play, Prodigal Daughter: A Comedy in One Act (Molesworth Hall, 24 April 1914), as a benefit for Irish Women’s Franchise League [see infra]; served as vice-chairman of the Irish Citizen Army, when founded as a defensive force, 1913; wrote extensively on questions of nationality and democracy in the Irish Citizen and contrib. a 4-page open letter asking Thomas MacDonagh to reconsider his militarist policy and his implicit anti-feminism (22 May 1915); organised Peace Patrol in 1916, and risked his life to save a wounded officer [Capt. Pinfield] shot at Dublin Castle; he was taken as hostage on British-army raid led by Capt. J. C. Bowen-Colthurst, who then had him summarily shot [in the back] by a friing party on the following morning in Portobello Barracks, 16 April 1916; afterwards buried there secretly in a sack and quicklime; |

|

called by Seán O’Casey ‘the ripest ear of corn that well in Easter Week’; P. S. O’Hegarty prepared a bibliography in 1936 [joined with another of Terence MacSwiney]; his widow wrote an account of her husband’s death, and conducted a campaign for his vindication and the trial of his murderer, assisted by Sir Francis Fletcher Vane, who lost his commission through his intervention; James Stephens called Skeffington the most absurdly courageous man he ever met; he is McCann in James Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist (1916); The Prodigal Daughter was revived by Donal O’Kelly as a rehearsed-reading at the Sheehy Skeffington School for Social Justice and Human Rights in April 2014; he repeatedly sounded the opinion that Parnell and afterwards Redmond had drawn the Irish Parliamentary Party to close to the English Liberal Party at risk to Irish independence. DIW DIB DIH FDA OCIL |

|

||

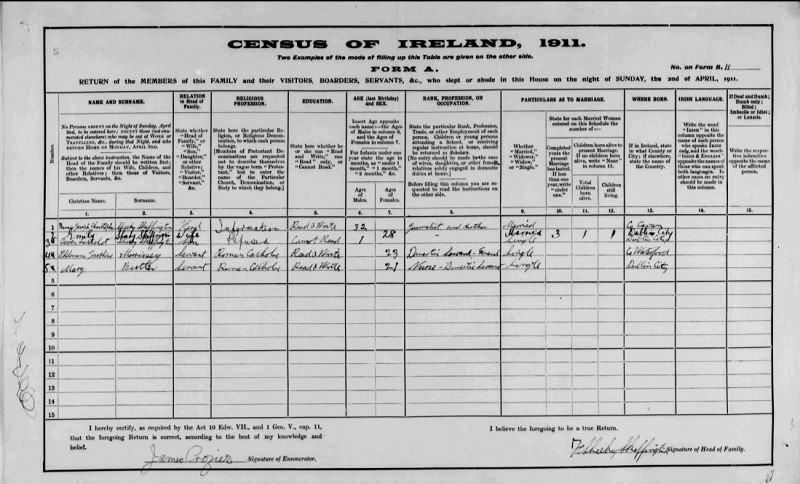

| Note that the family name is given as “Sheehy Skeffington” rather that “Sheehy-Skeffington” - in the 1911 Census. not also that ‘Information Refused’ appears under ‘religious Profession’ for both Francis and Hanna while both also appear as ‘journalist and author’ under ‘Rank, Profession, or Occupation.’ There are also a ‘Domestic Servant’ (Philomena Josephine Morrissey) and a ‘Nurse-Domestic Servant’ (Mary Butler) in the household but no children. | ||

|

||

| [ Click image to see enlargement - as attached; or go online for pdf. ] | ||

| Public Records / National Census ] - online |

[ top ]

Works| Monographs |

|

| Fiction |

|

| Drama |

|

| Pamphlets |

|

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical details

The Prodigal Daughter ‘The 2014 School will see the centenary reading, by Donal O’Kelly and colleagues, of The Prodigal Daughter, a play by Frank Sheehy Skeffington. It was first performed in the Molesworth Hall on 24th April 1914, almost exactly a century ago, and the cast included Máire Walker, the leading actress of the Abbey Theatre, and Maria Perolz, a prominent figure in agitation circles of the time. It’s described as a comedy in one act - and it is both funny and short, with a few well-placed shots at the humbug of the times, and some nice resonance for nowadays. The action takes place in a small town where one of the leading families is in uproar, as the youngest daughter is returning on the train that day - from a spell in Mountjoy Jail for suffragette activities.’ (The Sheehy Skeffington School - online; accessed 31.12.2104.) Note that the foregoing notice is attended by an image of the cover of an edition of the play showing a profile portrait of the author. This is presumably of recent date. The original having appeared in the Irish Citizen for7 Nov. 1914 (pp.196-98).

See also “Irishman’s Diary”, in The Irish Times (28 April 2014: ‘The Prodigal Daughter is a comedy in one act by Francis Sheehy Skeffington, the pacifist, feminist, and all-round radical murdered by a deranged British army officer during Easter Week 1916. Its anti-heroine is Lily Considine, daughter of a grocer and publican who, as the play opens, is on the way home from a spell in jail for militant activities in support of female emancipation. Her shamed family gathers to greet what they expect will be a sadder, wiser young woman. The priest is also on hand to advise in the likely case that Lily wishes to pursue an immediate vocation with the Poor Clares - since, obviously, “nobody will marry her now”. But not only does the brazen hussy turn out to be unrepentant, her only regret is that she was incarcerated after breaking a single pane of glass, whereas her fellow jailbird, Grace O’Neill, managed to smash 23. [...] ‘The Prodigal Daughter was first performed in April 1914 at Molesworth Hall, Dublin, during the Women’s Suffrage Movement’s “Daffodil Fete”. A century on, next weekend - April 12th - it will be re-enacted in a “rehearsed reading” by actor Donal O’Kelly as part of the 2014 Sheehy Skeffington School.’ (The Irish Times, 28.04.2014 - online.)

[ top ]

|

||||

[ top ]

Criticism| Contemporary |

|

| Modern |

|

See Irish Booklover, vol. 8 [contemp.]; A. M. W. ‘Leading Statesmen of the Co-operative Commonwealth.’ Leader (15 November 1913) [satirical verses incl. Yeats, AE, and Skeffington as ‘Skeffy’]; George Bernard Shaw, ‘On Behalf of an Irish Pacifist’, in The Matter with Ireland [ed. Dan Lawrence & David Greene] (London: Hart Davis/NY: Hill & Wang 1962), pp.90-92; Monk Gibbon, ‘Murder in Portobello Barracks,’ in Inglorious Soldier (1968), pp. 29-84; Richard Kain, Dublin in the Age of William Butler Yeats and James Joyce (Oklahoma UP 1962; Newton Abbot: David Charles 1972), espec. p.93f. |

| See also Michael Collins: His Own Story, by Hayden Talbot (1923) - Chap. XI: “The Murder of Francis Sheehy Skeffington” - available at Collins website - online. The author writes: ‘Colthurst whipped out his revolver and shot him dead.’ Also relates that Colthurst Bowen’s properties in Cork were burnt and, erroneously, that he died at the Front where he was afterwards sent. (In fact a brother died at the Front and Colthurst-Brown moved to Canada.) |

[ top ]

Commentary

James Stephens, Insurrection in Dublin (Maunsel 1916), p.50ff.: ‘[...] I met D. H. His chief emotion is one of astonishment at the organizing powers displayed by the Volunteers. We have exchanged rumours, and found that our equipment in this direction is almost identical. He says Sheehy Skeffington has been killed. That he was arrested in a house wherein arms were found, and was shot out of hand. / I hope this is another rumour, for, so far as my knowledge of him goes, he was not with the Volunteers, and it is said that he was antagonistic to the forcible methods for which the Volunteers stood. But the tale of his death was so persistent that one is inclined to believe it. / He was the most absurdly courageous man I have ever met with or heard of. He has been in every trouble that has touched Ireland these ten years back, and he has always been in on the generous side, therefore, and [50] naturally, on the side that was unpopular and weak. It would seem indeed that a cause had only to be weak to gain his sympathy, and his sympathy never stayed at home. There are so many good people who ‘sympathise’ with this or that cause, and, having given that measure of their emotion, they give no more of it or of anything else. But he rushed instantly to the street. A large stone, the lift of a footpath, the base of a statue, any place and every place was for him a pulpit; and, in the teeth of whatever oppression or disaster or power, he said his say.’ [Cont.]

James Stephens (Insurrection in Dublin, 1916) - cont.: ‘There are multitudes of men in Dublin of all classes and creeds who can boast that they kicked Sheehy Skeffington, or that they struck him on the head with walking sticks and umbrellas, or that they smashed their fists into his face, and jumped on him when he fell. It is by no means an exaggeration to say that these things were done to him, and it is true that he bore ill-will to no man, and that he accepted blows, and indignities and ridicule with the pathetic candour of a child who is disguised as a man, and whose disguise cannot come off. His tongue, his pen, his [51] body, all that he had and hoped for were at the immediate service of whoever was bewildered or oppressed. He has been shot. Other men have been shot, but they faced the guns knowing that they faced justice, however stern and oppressive; and that what they had engaged to confront was before them. He had no such thought to soothe from his mind anger or unforgiveness. He who was a pacifist was compelled to revolt to his last breath, and on the instruments of his end he must have looked as on murderers. I am sure that to the end he railed against oppression, and that he fell marvelling that the world can truly be as it is. With his death there passed away a brave man and a clean soul. / Later on this day I met Mrs. Sheehy Skeffington in the street. She confirmed the rumour that her husband had been arrested on the previous day, but further than that she had no news. So far as I know the sole crime of which her husband had been guilty was that he called for a meeting of the citizens to enrol special constables and prevent looting.’ (p.52; see in separate window - attached.)

Sean O’Casey [as P. Ó Cathasaigh], The Story of the Citizen Army (Maunsel 1919), Chap. XI [on the Rising] - on Francis Sheehy-Skeffington: ‘Unwept, except by a few, unhonoured and unsung - for no National Society or Club has gratefully deigned to be called by his name, - yet the ideas of Sheehy-Skeffington, like the tiny mustard-seed today, will possibly grow into a tree that will afford shade and rest to many souls overheated with the stress and toil of barren politics. He was the living antithesis of the Easter Insurrection; a spirit of peace enveloped in the flame and rage and hatred of the contending elements, absolutely free from all its terrifying madness; and yet he was the purified soul of revolt against not only one nation’s injustice to another, but he was also the soul of the revolt against man’s inhumanity to man. And in this blazing pyre of national differences his beautiful nature, as far as this world is concerned, was consumed, leaving behind a hallowed and inspiring memory of the perfect love that casteth out fear, against which there can be no law. / In Sheehy-Skeffington, and not in Connolly, fell the first martyr to Irish Socialism, for he linked Ireland not only with the little nations struggling for self-expression, but with the world’s Humanity struggling for a higher life. [...] So will the sown body of Sheehy-Skeffington bright forth, ultimately, in the hearts of his beloved people, the rich crop of goodly thoughts which shall strengthen us in all our onward march towards the fuller development of our National and Social life.’ [64]

Further (O’Casey): his ideas were like ‘the tiny mustard seed’ that would grow into a tree that will afford shade and rest to many souls overheated with the stress and toil of barren politics; ‘his beautiful nature’ was consumed in ‘the blazing pyre of national differences’; he was ‘the ripest ear of corn that fell in Easter Week.’ (Quoted in Paul Coston, in ‘Prelude to Playwriting’, Ronald Ayling, ed., Sean O’Casey: Modern Judgements, 1969, p.55.)

[top ]

| Monk Gibbon, Inglorious Soldier (London: Hutchinson 1968)— |

|

[top ]

Robert Lynd, ‘Memoir of Tom Kettle by Mary Kettle’, prefixed to The Ways of War (1917), cites [Kettle]’s encomium: ‘uncompromising and radically gentle idealist ... It would be difficult at any time to convey in the deadness of language an adequate sense of the courage, vitality, superabundant faith, and self-ignoring manliness which were the characteristic things we associate with Francis Sheehy-Skeffington ... [&c.]’ (Also quotes Guyau and Robert Buchanan).

Maurice Headlam, Irish Reminiscences (1947): ‘There was another letter [in Sinn Féin, 8 August, 1914] from poor little Sheehy-Skeffington, a “pacifist” who was mistaken for a Sinn Feiner and shot in the Rebellion of 19I6, in which he shows that he swallowed entire the German propaganda, and which ends:- “After days of patience and restraint under the menace -days every one of which must have cost Germany dear - the German Emperor decided to strike out at the net which was entangling his country; and at once the conspirators (England, France and Russia, that is) howl that he is the aggressor.”’ (p.147.)

Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (OUP 1959): ‘His friends took the opposite view [of Yeats’s The Countess Cathleen, premiered 8 May 1899]. As soon as the performance was over, Skeffington and others composed a letter of protest to the Freeman’s Journal, and it was left on the table in the colelge next morning so that all who wished might sign it. Joyce was asked and refused. The signers included Kettle, Skeffington, Byrne and Richard Sheehy. They wanted to claim a role for intellectual Catholics in Dublin’s artistic life, but picked the worst possible ocasion. Their letter, published [...] on May 10, was intended to be patriotic but only succeeded in being narrow-minded. It preofessed respect for Yeats as a poet, contempt for him as a thinker. His subject was not Irish, his characters were travesties of the Irish Catholic Celt. “We feel it our duty”, they wrote, “in the name and for the honour of Dublin Catholic students of the Royal University, to protest against an art, even a dispassionate art, which offers as a type of our people a loathesome brood of apostates.” The letter must have sounded to Joyce like something satirised in an Ibsen play. His refusal was remembered against him and resented as much as their alacrity to sign.’ (Richard Ellmann, James Joyce, OUP 1959; 1965 Edn., p.69.)

See also Ellmann, ed. Selected Letters of James Joyce (London: Faber 1975): ‘In the Freeman’s Journal of 4 February 1907, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington is quoted as saying at the debate [on J. M. Sygne’s The Playboy of the Western World, held at the Abbey on 4 Feb. 1907] that he was both for and against. “The play was bad, the organised disturbance was worse, the methods [of the police] employed to quell that disturbance were worst of all.” Richard Sheehy declared, “The play was rightly condemned as a slander on Irishmen and Irishwomen. An audience of self-respecting Irishmen had a perfect right to proceed to any extremity.”’ (Ellmann, op. cit., p.147, n.2; also see longer extract under Synge, infra.)

Patricia Craig, Elizabeth Bowen (London: Penguin 1986): ‘Some people proceeded to lose their heads, among them an army-officer cousin of Elizabeth’s named Captain Bowen-Colthurt. A well-known Dublin pacifist, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, was taken up in the act of restraining would-be looters, in the wake of the Rising. On the night following his odd arrest he was obliged to accompany a military party through the streets of Dublin, and witnessed the shooting, by Captain Bowen-Colthurst, of a boy named Coade. Next morning the [43] Captain organised the hasty execution, in the prison yard [sic], of Sheehy-Skeffington and two of his fellow prisoners (journalists unconnected with the nationalist movement.) Bowen-Colthurst was later court-martialled and declared insane, but not before he’d been posted to Newry in command of troops.’ (p.43-44.)

Margaret Ward, ‘“The Suffrage Above All Else!”: An Account of the Irish Suffrage Movement”, in Irish Women’s Studies: A Reader, ed. Ailbhe Smyth (Dublin: Attic Press 1993): ‘the Home Rule Bill finally became law in September [1914] , but was immediately shelved until the end of the First World War. The problem of Uslter has still not been resolved and armed conflict appeared ever more likely as men continued to join the Ulster Volunteers and the Irish Volunteers. Political allegiances had no convenient geographic delineation: there were unionist women in the south of Ireland, notationalist women in the North. Would it be possible for them to retain (or develop) feminist sympathies while faces with the prospect of incorporation into a new state they opposed? Francis Sheehy Skeffington saw the two ideologies of feminism and pacificism as indivisible entities: their antithesis the male cult of violence. he was prepared to admit that feminism did not necessarily entail holding the same political views, but affirmed his belief in the potentially constructive qualities of feminism. In this hope, he began to urge unionist women in the south to adopt a realistic approach to the situation: accepting that home rule was on the cards, they should now work to ensure representation of women in the new parliament. And Ulster women should also continue to work for the suffrage cause, as insurance policy (if Ulster did opt out of home rule) against being abandoned by Carson as nationalist women had already been abandoned by Redmond. (Irish Citizen, 1 Oct. 1914).’ (Ward, op. cit., p.38.)

Declan Kiberd: ‘The Elephant of Revolutionary Forgetfulness’, in Revising the Rising, ed. Máirín Ní Dhonnchadha & Dorgan (1991): ‘There was one participant in the events of 1916 who so perfectly achieved this transcendency old [English/Irish] polarities that he was shot in the very space he opened between the traditional enemies, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington. A pacificist and crusader for women’s rights, he was also a socialist who ws proud to name himself a friend of the republicans. In a magnificent letter to Thomas MacDonagh just before the Rising, he praised the future rebel’s ideas, but denied that the war they proposed could be ‘manly’ or anything better than ‘organised militarism’. The questions raised in his letter are still pertinent, why are arms so glorified?; will not those who rejoice in barbarous warfare inevitably come to control such an organisation?; why are women not more centrally involved? ‘When you have found and clearly expressed the reason [...]’, he added, ‘you will be close to the reactional element in the movement itself’ (‘An Open Letter to Thomas MacDonagh’, in Owen Dudley Edwards and Fergus Pyle, eds., 1916, The Easter Rising, MacGibbon & Kee 1967; see longer extract - as infra).

[ top ]

Quotations

Michael Davitt: Revolutionary, Agitator and Labour Leader [1908] (NY Edn. 1909): ‘It is curious, in the light of the attitude of Davitt and Parnell respectively at the time of the Split, to note that during these years Davitt repeatedly gave expression to his apprehension that Parnell was drawing too close to the Liberal party, and that the independence of the Irish party was in danger of being sapped in consequence. Just as he did not hesitate later and earlier to reprobate Parnell for his ill-timed hostility, largely on personal grounds, to the Liberals, so he fear- lessly attacked Parnell at the time when the latter was indeed inclined to be subservient to the Liberal party, and was in effect paving the [159] way for his own downfall, by accustoming his followers to look upon the Liberal alliance as the all-important thing. Davitt’s doubts on this point continued up to the eve of the divorce court proceedings which were the beginning of the end for Parnell.’ (pp.159-60; available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 01.01.2015.)

“A Forgetten Aspect of the University Question” (pamphlet; jointly with another by James Joyce, Dublin 1901) - Opening:W. B. Yeats as playwright: Skeffington complained at Yeats’s apparent representation of the ‘type of our people [as] a loathesome brood of apostates’ in Countess Cathleen, in a letter to The Freeman’s Journal (10 May 1899). Of Cathleen Ni Houlihan, he later wrote: ‘The play was right condemned as a slander on Irishmen and Irishwomen. An audience of self-respecting Irishmen had a perfect right to proceed to any extremity.’ (quoted in Stan Gèbler Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist, Poynter 1975, p.135.)

| In all the history of the Irish University Question, it in astonishing I how little attention has been given to that aspect of it which concerns the position of University Women, and how generally it is assumed that the matter is one for discussion and settlement by men only. However, the action of the Royal University Commission in inviting evidence from the leading Colleges for women will, probably, ensure adequate recognition of the feminine claim in all future discussions of the subject. To help in the exposition of that claim, to show its basis, and to state its objects, is a task specially appropriate to the journal which aims at being “ the orsran of all classes of Catholic students engaged in University life.” To do so is all the more necessary, because Irishwomen have not as yet grasped the need for agitation, and their silence may lead opponents to believe that their claim is non-existent or negligible. Yet a glance at the Calendar of the Royal University should suffice to dispel this delusion and to prove that, if not formulated in words, this claim is, nevertheless, a strong and growing force, being couched in the still more effective expression of deeds. Ever since the Charter of the University was granted the numbers and the successes of the women graduates have been steadily increasing. From the list of those who have obtained honours with the degree of B.A. during the last seventeen years we derive the following figures [table follows]. (p.3.) |

|

—See full text version, with James Joyce’s “The Day of the Rabblement” - as attached. |

[ top ]

‘An Open Letter to Thomas MacDonagh’, in Irish Citizen (22 May 1915): [...] As you know, I am personally in full sympathy with the fundamental objects of the Irish Volunteers. When you shook off the Redmondite incubus last September, I was on the point of joining you. had your Executive accepted my suggestion - to state definitely that it stood for the liberties of the people of Ireland “without distinction of sex, class or creed” - I would have done so at once. I am glad now I did not. For, as your infant movement grows towards the stature of full-grown militarism, its essence - preparation to kill - grows more repellent to me. [...] High ideals undoubtedly animate you. But has not really every militarist system started with the same high ideals? [...] I am opposed to partition; but partition could be defeated at too dear a price. [He ends with an exhortation to pacificism] Think it over before the militarist current draws you too far from your humanitarian anchorage.’ (Owen Dudley Edwards & Fergus Pyle, eds., 1916: The Easter Rising, 1968, pp.149-52.) [Cont.]

‘An Open Letter to Thomas MacDonagh’ (Irish Citizen, 22 May 1915) - further extracts: ‘You trace war, with perfect accuracy, to its roots in exploitation […] in the same speech you boasted of being one of the creators of a new militarism in Ireland’ - ‘Why are women left out? Consider carefully why; and when you have found and clearly expressed the reason why women cannot be asked to enrol in this movement, you will be close to the reactionary element in the movement itself.’ - ‘[W]hen you have found and clearly expressed the reason, you will be close to the reactionary element in the movement itself’ - ‘Think it over, before the militarist current draws you to far from your humanitarian anchorage.’ (‘Open Letter to Thomas MacDonagh’, in Irish Citizen, 22 May 1915; see Kiberd, under Commentary, supra.)

A Forgotten Small Nationality (in Century Magazine, Feb. 1916; rep. separately with another by Hanna Sheehy Skeffington [NY 1917]): ‘England has so successfully hypnotized the world into regarding the neighboring conquered island as an integral part of Great Britain that even Americans gasp at the mention of Irish independence. Home rule they understand, but independence ! “How could Ireland maintain an independent existence?” they ask. “How could you defend yourselves against all the great nations?” I do not feel under any obligation to answer this question, because that objection, if recognized as valid, would make an end of the existence of any small nationality whatever. All of them, from their very nature, are subject to the perils and disadvantages of independent sovereignty. I neither deny nor minimize these. But the consensus of civilized opinion is now agreed that they are entirely outweighed by the benefits which complete self-government confers upon the small nation itself, and enables it to confer on humanity. If the reader will not admit this, I will not stay to argue the matter with him. I will merely refer him to the arguments in vogue in favor of the independence of Belgium as against Germany, or of the Scandinavian countries as against Russia.’ (p.3.)

[Cont.]: ‘[...] For it is the essence of the Irish case that Ireland has no concern in this war. The pretense that it was being waged in behalf of Belgium and of the principle of small nationalities imposed on a few, but not for long; the frank declaration of the London Times on March 8 that England is in this war for her own interests and for the preservation of her dominance over the seas, is generally recognized as stating the position accurately. Even if Belgium were the cause of the war instead of an incident in it, there would still be no reason why Ireland, of all countries, should plunge into the fray. Ireland is the most depopulated and impoverished country in Europe, thanks to the beneficent English rule of the last century, and has no blood or money to spare; and if Holland and Denmark and Sweden and Switzerland, all richer and more densely populated than Ireland, still feel that it is their duty to keep out of the war, a fortiori it is the duty of Irish statesmen to use every effort to keep their people out of it. Ireland’s highest need is peace and the peaceful development of her resources; not a man can be spared for any chivalric adventure. Belgium, hard pressed as it is, has not yet suffered a tithe of what has been endured by Ireland at the hands of England, and [10] Ireland is still bleeding at every pore from the wounds England inflicted. Thus even were the Belgian excuse true, there would be higher reasons of self-interest to keep Irish attention concentrated on our own problems.’ (pp.10-11.)

[Cont.:] ‘Without any illusions, then, about Germany, but with a clear vision of the English Empire as the incubus on Ireland, Irish Nationalists decided from the start of the war that it was Ireland’s interest and duty to remain neutral as far as possible. In these days of small nationalities Ireland’s right to take an independent line on the war cannot be contested, at all events by those who are fighting “German militarism.” Being held by force by the empire, and plentifully garrisoned both by troops and armed police, - the police have been refused permission to join the army, though many of them have volunteered, because the Government wants them to keep Ireland down, - it was not possible for Ireland to be neutral in the full sense. Irishmen who had joined the army in time of peace, through economic pressure for the most part, had to fulfil their duties as reservists; Ireland’s heavy burden of the war taxation could not be evaded. But, as one of Ireland’s best known literary men put it, Ireland preserved “a moral and intellectual neutrality”; and the individual sympathies of the people, while not “pro-German” in any positive sense, were and are, distinctly anti-English.’ (p.12; for full-text, see attached.)

[ top ]

References

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), listed as Skeffington, Francis Sheehy; n Dark and Evil Days (/b916), about the Kyan family in 1798; Women’s Suffrage, Labour Reform and International Peace.; b. Co. Cavan, 1878, UCD Chancellor’s Gold Medal. Shot by Colthurst in 1916. IF lists, In Dark and Evil Days (1916), a Wexford family in 1798.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, p.853 [John Bowen-Colthurst, a relative of Elizabeth], [1002, index. err.], pp.1003-04 [Griffith’s response to Sheehy-Skeffington’s outraged defence of Ryan as an nationalist, following Griffith’s ambivalent encomium/obituary of 12 April 1913 in Sinn Féin], [1020 bio-note, err.]; 1020 [fnd. The National Democrat, ed. with Frederick Ryan, 1907]. Bibl., Thomas Kettle, biog. [p.1018], Roger McHugh, ‘Thomas Kettle and Francis Sheehy-Skeffington’, in Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Shaping of Modern Ireland (London: Routledge & KP 1960); The Field Day Anthology of Irish WritingVol. 3, selects ‘War and Feminism’, and ‘Speech from the Dock’, in which he makes a point about Carson’s avowal of unconstitutional action [‘if Sir Edward Carson, as a reward for saying that he would break every law possible, gets a Cabinet appointment, what is the logical position as regards myself?’]; ed. remarks that the same half-heartedly urged by defence barrister A. M. Sullivan in defence of Roger Casement [Vol. 3, pp.712-14]; also p.809, as supra]. Bibl., F. Sheehy-Skeffington, ‘Open Letter to Thomas MacDonagh’, in Irish Citizen 22 May 1915, rep. in Owen Dudley Edwards & Fergus Pyle, eds., 1916, The Easter Rising (MacGibbon & Kee 1968) [Vol.3, p.566].

Libraries & Booksellers: Belfast Public Library holds Michael Davitt (1908). Hyland Books (Cat. 214) lists Eugene Sheehy, Law & Human Progress (1911) [Law Students Debating Soc. of Ireland [copy inscribed with auditor’s compliments.]

[ top ]

Notes

Irish Literary Theatre: When Yeats’s Countess Cathleen is premiered in May 1899, Sheehy composes and signs with others a protest: ‘We feel it our duty in the name and for the honour of Dublin Catholic students of the Royal University, to protest against an art even a dispassionate art, which offers as a type of our people a loathshome brood of apostates.’ (Skeffington was “Knickerbockers” to his fellow-students on account of his revolutionary legwear, and “Hairy Jaysus” to Joyce on account of his ethical pretensions.)

Heckler: Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, ‘who had been banned from entry to the Theatre Royal, nonetheless put on a clerical costume, became part of the crowd gathered there to hear the English prime minister and was “heckling” him about universal suffrage before being thrown out.’ (Margaret MacCurtain, ‘Women, the Vote and Revolution’, in Women and Irish Society, the Historical Dimension, ed. MacCurtain & Donncha Ó Corrain, Dublin 1978; quoted in Cheryl Herr, For the Land they Loved, 1991, p.61.)

Playboys? - Stan Gébler Davies writes: ‘Skeffington’s brother-in-law [?], wrote of Synge’s Playboy at the time of the riot: ‘the play was rightly condemned as a slander of Irishmen and Irishwomen. An audience of self-respecting Irishmen had a perfect right to proceed to any extremity.’ (See Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist, Davis-Poynter 1975, p.135.) Adrian Frazier writes: ‘As Sheehy Skeffington put it, /The play was bad, the organised disturbance was worse, and the methods used to quell the disturbance worst of all”’ (Skeffington, in ‘The Abbey Disturbance’ [letter], Daily Express, 5 Feb. 1907; Frazier, Behind the Scenes: Yeats, Horniman, and the Struggle for the Abbey Theatre, Berkeley: California UP 1990, p.215-16.)

| Joyce & Skeffington |

Pamphleteers: “A Forgetten Aspect of the University Question” (pamphlet; jointly with another entitled "The Day of the Rabblement" by James Joyce, Dublin 1901) - see extract, as supra.

Condolences: Skeffington, as McCann, is the occasion of an epiphany in Stephen Hero when, at the death of Stephen’s sister from peritonitis, he condoles: ‘I was sorry to heart of the death of your sister ... sorry we didn’t know at the time ... to have been at the funeral’. Stephen answers: ‘O, she was very young ... a girl’, to which McCann: ‘Still ... it hurts.’ Joyce added: ‘The acme of unconvincingness seemed to Stephen to have been reached at that moment.’

|

Eva Gore-Booth wrote verses at his death declaring that he was not alone, ‘for at his side does that scorned Dreamer stand/Who in the Olive Garden agonised’ [cited by Richard Kearney, ‘Myth and Terror’, in Crane Bag Book of Irish Studies, 1982, p.287.]

Capt. Bowen-Colthurst was found ‘guilty but insane’ in the courtmartial that charged him with the murder of Skeffington; he was imprisoned for a year and afterwards moved to Canada. There is an account of the court martial of Captain Bowen-Colthurst given by Louie Bennett in Louie Bennett by R. M. Fox (1955), p. 59ff. Note: The Colthursts, a titled family, acquired Blarney Castle in c.1847 and retain it still.

Capt. Bowen-Colthurst is cited in Irish Days, Indian Memories - V.V. Giri and Indian law Students at UCD, 1913-1916 (IAP 2016) - reviewed by Frank MacGabhann in The Irish Times (27 Jan. 2017): ‘Perhaps the most interesting aspect of the book is the somewhat far-fetched theory of a tenuous connection to one of the executions in 1916. Indian students were being vilified in a cheap Dublin scandal sheet called Eye-Opener, edited by a man called Thomas Dickson, a unionist. After seeing themselves described as “the Black Peril” and “vampires”, Indian students were upset and made complaints. The author thinks that it may be possible that these complaints may have led to Dickson’s undoing, perhaps by his coming to the notice of the authorities under the Defence of the Realm regulations. In any case, after arresting him on Tuesday of Easter Week, the crazed British officer, Captain JC Bowen-Colthurst, ordered the following day that Dickson be shot by firing squad in Portobello Barracks. Also ordered executed were the person whom the author conjectures Dickson may have been meeting about the Indian students, Patrick McIntyre, and, of course, Francis Sheehy-Skeffington, who had nothing to do with either of them.’ (See The Irish Times - online; accessed 30.01.2017.)

Referees: Threshold, No. 30 (Spring 1979), editorial quotes Skeffington’s application for the post of Registrar of NUI, ‘I will spare you the fatuity of testimonials’ (p.3).

Kith & kin?: Stephen Brown, in Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists E. Skeffington Thompson, dg. of John Foster, last Speaker of Irish House of Commons; ardent Nationalist, who founded Southwark Junior Irish Literary Society with Mrs Rae in c.1889; author of Moy O’Brien (Gill [1887]; rep. 1914) [seeq.v.].

The Guard (2011): Sheehy-Skeffington’s name is outrageously given to one of the drug dealers (played by Liam Cunningham) in the Martin McDonagh-scripted box-office success The Guard (2011), with Brendan Gleeson in the lead. The film rated as the most successful Irish earner of all time in 2015.

[ top ]