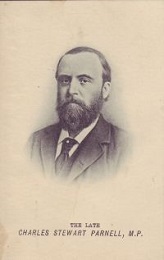

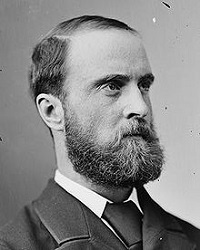

Charles Stewart Parnell (1846-1891)

Life

| 1846: b. 27 June, Avondale Hse., Rathdrum, Co. Wicklow; son of Hohn Henry Parnell and descended from Cheshire family who purchased land in Queen's County (now Laois) during the Stuart restoration; son of the first Parnell in Ireland was Thomas Parnell [q.v.], archdeacon of Clogher and a friend of Jonathan Swift [q.v.]]; his g-father Sir John Parnell was Chancellor of the Exchequer, 1785, and an anti-Union MP in the Dublin Parliament - a son of whom inherited Avondale, Co. Wicklow, from Samuel Haes in 1795; C.S. Parnell’s mother was Delia Tudor [née Stewart], from whom Parnell reputedly acquired his aversion to the English, was an American and the dg. of Commodore Charles Stewart (“Old Ironsides”), a naval officer who defeated British ships in several actions; mother; ed. partly at Yeovil, Somerset, a girls’ school where he contracted typhoid; thereafter priv. ed., and Kirk Langley, Derbyshire (expelled), and Great Ealing School; inherited estate in 1859; moved with family to Dublin; attended crammer in Chipping Norton; proceeded to Magdalene College, Cambridge; sent down in 1869; travelled to continent, and visited his brother John Howard Parnell (1843-1923); then farming in Alabama; |

| 1875: elected IPP MP for Meath, 1875; declared ‘as publicly and as directly’ as he could that he did not ‘believe, and never shall believe, that any murder was committed at Manchester’ (in response to Sir Michael Hicks Beach’s allusion the the ‘Manchester murderers’ [viz, “Manchester Martyrs” of 1865], June 1876; President Home Rule Confederation, 1877; ‘New Departure’ (so called by John Devoy), 1878; President of newly-founded Land League, Oct. 1879 (‘Keep a firm grip on your homesteads’); and visited USA with John Dillon and Tim Healy, Dec. 1879-Feb. 1880; addresses American House of Representatives [Congress]; collected £40,000 in the States, enabling an independent policy; elected MP for Cork, 1880, as a result of a Tory scheme to split the Whig vote, and represented Cork to the end of his career; elected chairman of the IPP, 1880, advocating the model of ‘Grattan’s Parliament’; Capt. O’Shea returned for Galway in 1880 election; commenced affair with Katharine O’Shea (née Woods), in the course of which the couple had three children - the first being Claude Sophie, born in 1881 (and died shortly after) while O’Shea was carrying message between Parnell and the Government; promoted Boycotting policy against coercion; challenged to duel by Capt. O’Shea, July 1881; |

| 1881: heavily engaged in Wicklow Arklow harbour schemes, 1881; Gladstone’s Land Bill introduced, 7 April 1881, second reading 25th April; acquired The Flag of Ireland from Richard Pigott, and reissued it as United Ireland under the editorship of William O’Brien; suspended from House of Commons, 1 Aug. 1881; spoke at Cork demanding full political freedom (‘those who want to preserve the golden link of the Crown must see to it that it shall be the only link connecting England and Ireland’); denounced by Gladstone, speaking at Cloth Hall banquet, Leeds, 8 Oct., 1881 (‘the resources of civilisation against its enemies are not yet exhausted’); spoke violently against Gladstone’s Land Act in response, Wexford, 9 Oct. (‘Ah, If I am arrested Captain Moonlight will take my place’); arrested under Special Powers; 13 Oct.; agreed to “No Rent Manifesto”, with William O’Brien and others, 18 Oct. 1881; |

| 1882: settled terms in ‘Kilmainham Treaty’, withdrawing Manifesto, with Gladstone, 1882, negotations being conducted through Justin McCarthy and later the O’Sheas; released 2 May 1882 [var. 9 April], and honoured in torchlit march, 5 May 1882; suppressed Ladies Land League; est. Irish National League to replace Land League, 17 Oct. 1882; Phoenix Park Murders, perpetrated by the Invincibles, 6 May 1882 [see note]; Parnell’s offer of resignation delivered to Gladstone by Capt. O’Shea after the murders, May 1882; Fenian dynamite campaigns in London, 1883, 1884; speech at Cork Opera House, 21 Jan. 1885 (eve of Gen. Election: ‘We cannot, under the British constitution, ask for more than the restitution of Grattan’s parliament. But no man has the right to say to his country, “thus far shalt thou go and no further”, and we have never attempted to fix the ne plus ultra to the progress of Ireland’s nationhood, and we never shall’ [see note, infra]; sweeping election victory returns 86 seats and gains control of balance of power at Westminster; Gladstone’s conversion to Home Rule, 1885; Parnell issues manifesto to Irish in Britain to support liberal candidates, 21 Nov. 1885; |

| 1886: First Home Rule Bill, introduced by Gladstone, 8 April 1886, and narrowly defeated; commenced to live with Katharine O’Shea at Eltham, summer 1886; withheld support from Plan of Campaign [1886-91] formulated for Land League by John Dillon, William O’Brien, Tim Harrington and others, and publ. in United Irishman (21 Oct. 1886), offering ‘fair’ rent and using it for Land League support if refused; Plan of Campaign declared ‘unlawful and criminal conspiracy’ by British Govt., Dec. 1886, and condemned by Pope Leo XIII, 20 April 1888; ‘Parnellism and Crime’ serial chiefly written by John Woulfe Flanagan [see note] and featuring facsimile letters purportedly by Parnell but actually forged by Richard Pigott, appeared in The Times, 1887-88 (7 March-17 April 1887), alleging his involvement with Land League activism [violence] in keeping with W. E. Forster’s charge that ‘crime dogged the footsteps of the Land League’ - and, more harmfully - with the Invincible murders at the Phoenix Park; |

| 1887:Capt. O’Shea publishes unflattering portrait of Parnell in The Times (2 Aug. 1888); Parnell Commission, Oct. 1888-Nov. 1889, leading to exposure of Piggot as a forger under cross-examination by Charles Russell, the result being delivered 1890; Parnell attends Lyceum theatre at height of Times Commission crisis; hailed in Westminster by thunderous applause from both sides of the house, he walked to his seat without any sign of acknowledgement; represented by Thomas Sexton at foundation of Tenants’ Defence Association, 15 Oct. 1889; O’Shea divorce filed Christmas Eve 1889 (though O’Shea himself had conducted 17 known affairs), granted 17 Nov. 1890 [var. 18 Nov. DIH], 1890; details emerge of assumed names, including “Mr. Fox”; much engaged with quarries in Arklow, 1891; fnd. Irish Daily Independent, 1891; |

| 1891: Gladstone withdraws Liberal-Party support of his leadership, Nov. 1891; Michael Davitt calls for his resignation in Labour World (20 Nov.); re-elected chairman, 25 Nov.; Gladstone published his position in a letter to John Morley [‘leadership ... almost a nullity ’] (26 Nov.); Irish Catholic hierarchy [of bishops] announces crisis meeting for 3 Dec., 18 Nov.; hierarchy publishes “Manifesto to the Irish People” (29 Nov.), attacking Gladstone, the Liberals and a section of his own party; Dillon and O’Brien, then in America, revoke their support of Parnell; Catholic hierarchy call on the Irish people to reject Parnell’s leadership, 3 Dec.; Party split occurs in Committee Room 15 of the House (Westminster), Sat. 6 Dec. 1890, forty-four members walking out behind McCarthy [var. 55 to 33]; aggravated by personal references to Parnell’s use of the party’s “Paris Funds”; |

| 1891: Parnell seizes control of United Ireland, then under the deputy-editorship of Matthew Bodkin - who brought out The ‘Supressed’ United Ireland, and later The Insupressible up to 14 Jan. 1891; CSP meets William O’Brien - by then returned from America - at Boulogne, his preferred successor, though breaking off leadership succession talks without resolution; conducted a political tour of Ireland to regain popular support, attracting Fenian ‘hillside men’ to his side with the policy of ‘no English dictation’; m. Katharine O’Shea, 25 June, 1891, on which day the Catholic hierarchy issued a condemnation of his conduct, only Edward O’Dwyer, bishop of Limerick withholding his signature; loses support of Freeman’s Journal; settled with Kitty at 9, Walsingham Tce., W. Brighton; |

| 1891: quicklime thrown at his eyes by hostile crowd in Castlecomer; addressed crowd in pouring rain at Creggs on Galway-Roscommon border [var. Mayo], and contracted pneumonia, 27 Sept.; returned to Dublin, thence to Brighton, departing by the mail boat, 30 Sept. (‘I shall be all right. I shall be back next Saturday week’); d. of pneumonia, near midnight, 6 Oct., Brighton; bur. Glasnevin Cemetery, 11 Oct., his body having been brought back to Ireland; a star is supposed to have fallen ‘in broad daylight’ when his coffin was lowered into the grave (as recalled by W. B. Yeats and Standish O’Grady); his death-date, 6 Oct., quickly came to be known as Ivy Day - memorialised in James Joyce’s Dubliners story (“Ivy Day in the Committee Room”); a portrait by Sidney Hall serves as frontispiece to Memoir (1914) by his brother Howard - who refers to his as Charley throughout. |

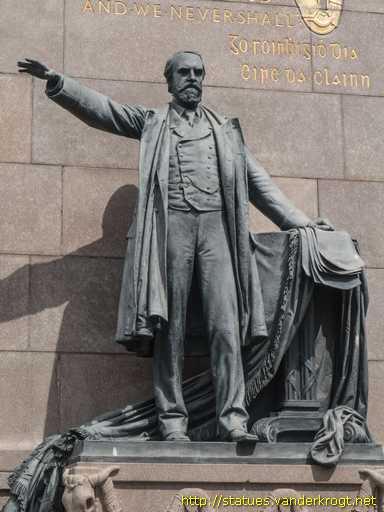

Posthum.: former Great Britain St. was renamed Parnell St. after his death; a bronze figure of Parnell by Augustus St Gaudens, as part of the Parnell Monument, was unveiled in 1911 - the foundation stone having been laid by John Redmond in front of the Rotunda, O’Connell St., Dublin, in 1899 - with the inscription on the obelisk from the Cork speech of 1885 [‘no man has a right to set a boundary to the march of a nation ...’]; Avondale was sold to the State in 1899 by John Howard Parnell - who is a minor character in Joyce’s Ulysses, where he is seen playing chess; an Annual Charles Stewart Parnell Summer School convenes at Avondale, Co. Wicklow; Parnell’s speeches were collected as by Jennie Wyse-Power as Words of the Dead Chief, with an introduction by Miss Anna Parnell (1892); an early life was written by Harry O’Brien in 1898. |

| ODNB JMC DIB DIH DIL OCEL FDA OCIL |

[ top ]

|

|

|

| Gladstone - Parnell - William O’Brien: Remarks on the O’Shea Divorce Trial |

|

Parnell (letter to Wm. O’Brien prior the divorce trial): ‘You may rest quite sure that if this proceeding ever comes to trial (which I very much doubt) it is not I who will quit court with discredit.’ [p.16.] William O’Brien: ‘For myself, I should no more have voted Parnell’s displacement on the Divorce Court proceedings alone than England would have thought of changing the command on the eve of the battle of Trafalgar in a holy horror of the frailties of Lady Hamilton and her lover.’ [p.18.] W. E. H. Gladstone (Prime Minister): ‘The continuance of Parnell’s leadership would render my retention of the leadership of the Liberal Party almost a nullity.’ [p.24.] |

| —All quoted in D. D. Sheehan, Ireland Since Parnell (1921), respectively pp.16, 18, 24 - available online. |

|

|

| The Parnell Monument, by Augustus St. Gaudens - unveiled in Upr. O’Connell Street, 1911. |

|

Criticism[ top ]

Works

Speeches collected as Words of the Dead Chief, being extracts from the public speeches and other pronouncements of C. S. Parnell ... with an introduction by Miss Anna Parnell, and a facsimile of portion [sic] of Mr Parnell’s famous manifesto to the Irish people (Dublin: Sealy, Bryers & Walker 1892); Michael Hurst and Alan O’Day, eds., The Speeches of Charles Stewart Parnell (Hambledon Press 1996), 304pp.Reprints, Jennie Wyse-Power, ed., Words of the Dead Chief: Being Extracts from the Public Speeches [...] of Charles Stewart Parnell, with introduction by Anna Parnell (UCD Press 2009), 192pp.

[ top ]

|

|

|

|

||||

[ top ]

| Canon P[atrick] A. Sheehan,The Graves of Kilmorna: A Story of ’67 (1915; 1918 Edn.) |

|

| See full-text copy in RICORSO Library - as .pdf [attached] |

|

| Chap. III: “The Death of a Leader” |

|

| Chap. IV: “An Appreciation of Parnell” |

|

|

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats (1)| Nobel Acceptance Speech (1923) |

| ‘The modern literature of Ireland, and indeed all that stir of thought that prepared for the Anglo-Irish war, began when Parnell fell from power in 1891. A disillusioned and embittered Ireland turned from parliamentary politics; an event was conceived; the race began, as I think, to be troubled by that event’s long gestation. ’ (“The Bounty of Sweden”, in Autobiographies, London: Macmillan 1955, p.559). [See commentary by Anne Fogarty - as infra.] |

“Mourn - and Then Onward”: ‘Parnell came down the road, he said to a cheering man: / “Ireland shall get her freedom and you still break stone.”’ “PARNELL’S FUNERAL”, ‘Under the Great Comedian’s tomb the crowd. / A bundle of tempestuous cloud is blown / About the sky; where that is clear of cloud / Brightness remains; a brighter star shoots down; / What shudders run through all that animal blood? / What is this sacrifice? Can someone there / Recall the Cretan barb that pierced a star? / Rich foliage that the starlight glittered through, / A frenzied crowd, and where the branches sprang / A beautiful seated boy; a sacred bow; / A woman, and an arrow on a string; / A pierced boy, image of a star laid low. / That woman, the Great Mother imaging, / Cut out his heart. Some master of design / Stamped boy and tree upon Sicilian coin. / An age is the reversal of an age: / When strangers murdered Emmet, Fitzgerald, Tone, / We lived like men that watch a painted stage. / What matter for the scene, the scene once gone: / It had not touched our lives. But popular rage, / Hysterica passio dragged this quarry down. / None shared our guilt; nor did we play a part / Upon a painted stage when we devoured his heart. / Come, fix upon me that accusing eye. / I thirst for accusation. All that was sung, / All that was said in Ireland is a lie / Bred out of the contagion of the throng, / Saving the rhyme rats hear before they die. / Leave nothing but the nothings that belong / To this bare soul, let all men judge that can / Whether it be an animal or a man. / The rest I pass, one sentence I unsay. / No loose-lipped demagogue had won the day. / No civil rancour torn the land apart. / Had Cosgrave eaten Parnell’s heart, the land’s / Imagination had been satisfied, / Or lacking that, government in such hands. / O’Higgins its sole statesman had not died. / Had even O’Duffy - but I name no more - / Their school a crowd, his master solitude; / Through Jonathan Swift’s dark grove he passed, and there / Plucked bitter wisdom that enriched his blood.’

W. B. Yeats (2) - “Come Gather Round Me, Parnellites”: ‘Come gather round me, Parnellites, / And praise our chosen man; / Stand upright on your legs awhile, / Stand upright while you can, / For soon we lie where he is laid, / And he is underground; / Come fill up all those glasses / And pass the bottle round. / And here’s a cogent reason, / And I have many more, / He fought the might of England / And saved the Irish poor, / Whatever good a farmer’s got / He brought it all to pass; / And here’s another reason, / That Parnell loved a lass. / And here’s a final reason, / He was of such a kind / Every man that sings a song / Keeps Parnell in his mind. / For Parnell was a proud man, / No prouder trod the ground, / And a proud man’s a lovely man, / So pass the bottle round. / The Bishops and the party / That tragic story made, / A husband that had sold his wife / And after that betrayed; / But stories that live longest / Are sung above the glass, / And Parnell loved his country / And Parnell loved his lass.’

On the death of Parnell: ‘Ireland was like soft wax for years to come’ (quoted in W. J. McCormack, Dissolute Characters: Irish Literary History through Balzac, Sheridan Le Fanu, Yeats and Bowen (Manchester UP 1993), p.193 [Chap.: “Yeats and Gothic Politics”].

W. B. Yeats (3): ‘[A] follower recorded that, after a speech that seemed brutal and callous, his hands were full of blood because he had torn them with his nails […] Mrs Parnell tells how upon a night of storm on Brighton Pier, and at the height of his power, he held her over the waters and she lay still, stretched upon his two hands, knowing that if she moved, he would drown himself and her.’ (A Vision, 1937 Edn., p.124).

Note: In a letter of Sept. 1936, Yeats refers to Henry Harrison’s Parnell Vindicated (1931), and comments that Mrs O’Shea was free woman when she met Parnell, and that ‘the Irish Catholic press had ignored his book. It preferred to think that the Protestant had deceived the Catholic husband.’ (Letters, ed. Wade, pp.892-93);

W. B. Yeats (4):

Further, ‘The fall of Parnell had freed imagination from practical politics, from agrarian grievance and political enmity, and turned to the imaginative nationalism, to Gaelic, to the ancient stories, and at last to lyric poetry and drama.’ (q. source; quoted in Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, ‘James Joyce and the Tradition of Anti-colonial Revolution’ [Working Papers Ser.] Washington State Univ. 1999, p.4, citing Dominic Manganiello, Joyce’s Politics, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1980, p.23, which cites Intro., Words upon the Windowpane, in Explorations, Macmillan 1962, p.343.)

Cf. Autobiographies, ‘A powerful class by terror, rhetoric, and organized sentimentality may drive their people to war, but the day draws near when they cannot keep them there; and how shall they face the pure nations of the East when the day comes to do it with but equal arms? I had seen Ireland in my own time turn from the bragging rhetoric and gregarious humour of O’Connell’s generation and school, and offer herself to the solitary and proud Parnell as to her anti-self, buskin following hard on sock, and had begun to hope, or to half hope, that we might be the first in Europe to seek unity as deliberately as it had been sought by theologian, poet, sculptor, architect, from the eleventh to the thirteenth century. Doubtless we must seek it differently, no longer considering it convenient to epitomize all human knowledge, but find it we well might could we first find philosophy and a little passion.’ (1955, p.195.)

Note: Richard Ellmann writes in The Identity of Yeats (1948): ‘[T]the death of Parnell is described as if it were the death of some pagan god, and the ancient rite of eating the hero’s heart to obtain his qualities is introduced metaphorically to explain the course of Irish history after Parnell’s death.’ (p.208; quoted in W. J. McCormack, Dissolute Characters: Irish Literary History through Balzac, Sheridan Le Fanu, Yeats and Bowen, Manchester UP 1993, p.194.)

[ top ]

A contemp. elegy for Charles Stewart Parnell by Lionel Johnson

The poem is printed in Warre B. Wells, John Redmond (1919) but not included in Selected Poems (1908).

John Millington Synge - on sitting with a young girl in a carriage full of drunken men going to Dublin to commemorate Parnell at the eighth anniversay of his death: ‘The presence at my side contrasted curiously with the brutality that shook the barrier behind us. The whole spirit of the west of Ireland, with its strange wildness and reserve, seemed moving in this single train to pay homage to the dead stateman of the east.’ (Aran Islands, in Collected Works, Vol. 2, ed. Alan Price, OUP 1966, p.124; quoted in Anne Gallagher, ‘Tramps, Tinkers and Beggars in the Plays of J. M. Synge’, UUC UG Diss., 2010.)

[ top ]

|

| “The Shade of Parnell” (1912) |

|

| “Home Rule Comes of Age” (1907), [on Nationalist MPs] |

|

| Ulysses (1922) |

|

|

|

|

| Finnegans Wake (1939) |

|

[ top ]

Louis-Paul Dubois, Contemporary Ireland (Dublin: Maunsel 1908): ‘Parnell shares with O’Connell the glory of being the greatest of Irish leaders. Like O’Connell he was a landlord and his family traditions were those of an aristocrat. Like him, too, he was overbearing, even despotic in temperament. But in all else Parnell was the very opposite of the ’Liberator.’ The Protestant leader of a Catholic people, he won popularity in Ireland without being at all times either understood or personally liked. In outward appearance he had nothing of the Irishman, nothing of the Celt about him. He was cold, distant and unexpansive in manner and had more followers than friends. His speech was not that of a great orator. Yet he was singularly powerful and penetrating, with here and there brilliant flashes that showed profound wisdom. A man of few words, of strength rather than breadth of mind - his political ideals were often uncertain and confused - he was better fitted to be a combatant than a constructive politician. Beyond all else he was a Parliamentary fighter of extraordinary ability, perfectly self-controlled, cold and bitter, powerful at hitting back. It was precisely these English qualities that enabled him to attain such remarkable success in his struggle with the English. Pride was perhaps a stronger motive with him than patriotism or faith.’ (Quoted in Capt. D. D. Sheehan, Ireland Since Parnell, London: Daniel O’Connor 1921, pp.32-33; see full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > History”, via index or attached.)

R. Mitchell Henry [MA, QUB], The Evolution of Sinn Féin (NY: Huebsch 1920; rep. 1971): ‘The pathetic and humiliating performance (of the Butt “Home Rulers”) was ended by the appearance of Charles Stewart Parnell, who infused into the forms of Parliamentary action the sacred fury of battle. He determined that Ireland, refused the right of managing her own destinies, should at least hamper the English in the government of their own house; he struck at the dignity of Parliament and wounded the susceptibilities of Englishmen by his assault upon the institution of which they are most justly proud. His policy of Parliamentary obstruction went hand in hand with an advanced land agitation at home. The remnant of the Fenian Party rallied to his cause and suspended for the time, in his interests and in furtherance of his policy, their revolutionary activities. For Parnell appealed to them by his honest declaration of his intentions; he made it plain both to Ireland and to the Irish in America that his policy was no mere attempt at a readjustment of details in Anglo-Irish relations but the first step on the road to national independence. He was strong enough both to announce his ultimate intentions and to define with precision the limit which must be placed upon the immediate measures to be taken. [...] He is remembered, not as the leader who helped to force a Liberal Government to produce two Home Rule Bills but as the leader who said “No man can set bounds to the march of a nation....” To him the British Empire was an abstraction in which Ireland had no spiritual concern; it formed part of the order of the material world in which Ireland found a place; it had, like the climatic conditions of Europe, or the Gulf Stream, a real and preponderating influence on the destinies of Ireland. But the Irish claim was, to him, the claim of a nation to its inherent rights, not the claim of a portion of an empire to its share in the benefits which the Constitution of that empire bestowed upon its more favoured parts.’ (Quoted in Capt. D. D. Sheehan, Ireland Since Parnell, London: Daniel O’Connor 1921, pp.33-34; see full text in RICORSO Library, “Criticism > History”, via index or attached.)

Marvin Magalaner, “The Problem of Biography” [Chap. 2], in Magalaner & Richard M. Kain, James Joyce: The Man, The Works, The Reputation [1956] (London; John Calder 1957): ‘For young Joyce to have known even vaguely of the brave fight waged by The Chief to recover the political ground lost by the assassinations, so that by 1886 it was possible for Gladstone to argue seriously in Parliament for an Irish Home Rule Bill, was bound to make the aftermath of the Parnell affair shockingly bitter. Parnell’s vindication during the libel trial of The Times was no preparation, even for hardened veterans in politics, for the fall which was to come just two years later over an issue that had nothing to do with the political well-being of Ireland. In the late 1880’s his supporters still attributed to him the strength of lions. He had seemingly weathered every storm and had come within hailing distance of securing a free Ireland. It appeared appropriately paradoxical, therefore, that his downfall should come, not at the hands of his English enemies in and out of Parliament, but through the manipulations of a political adventurer, Captain W. H. O’Shea, with whose wife Parnell had long been carrying on an affair. Named corespondent in the politically inspired divorce proceedings, Parnell, a proud figure to the last, maintained a silent aloofness. So strong was his position in Ireland that after the divorce trial and its attendant disclosures, he was elected unanimously by party heads as their leader. Only then were political lines drawn and the fight to depose him begun. Only then did T. M. Healy give vent to his real feelings of hatred for his superior - the sordid story of which nine-year-old Joyce told in his first published work, Et Tu, Healy! So Parnell was unceremoniously dropped by the very people whose cause he had brought to the edge of success. This was in December 1890. In the following year, Parnell died.’ (p.34.)

Marvin Magalaner, “The Problem of Biography”, 1957) - further remarks incl. the following: ‘If Gladstone could tell an interviewer in 1897 that ‘Parnell was the most remarkable man I ever met ... . and the most interesting ... Parnell was supreme all the time,” [Henry Harrison, Parnell Vindicated [...; &c.], 1931, p.68] it is no wonder that to an unsophisticated child [i.e., James Joyce] who looked to his father for a sense of values Parnell should have assumed superhuman proportions.’ (p.34; see further under J. M. Healy and James Joyce.) Magalaner quotes Lord Morley: ‘I cannot explain it [the public outpouring of emotion] save by the intensity of countless private griefs and by the reactions of a general sense of consternation as at the happenings of something incredible and monstrous-that together create a sort of collective nerve tensity which carries individuals out and away beyond their normal depth. Certain it is that public sorrow in Ireland was manifest on a scale and to a degree unparalleled... . And the public funeral in Dublin was an immense spectacle of human emotion ...’ (In Harrison, Parnell Vindicated [... &c.], 1931, pp.94-95; Magalaner, op. cit., p.36.) Magalaner concludes: ‘No public event in his [Joyce’s] life did more to color his personality and his work than Ireland’s treatment of The Chief.’ (Ibid., p.37.)

[ top ]

F. S. L. Lyons, ‘The idea of the lonely, heroic figure, deserted by his party, fighting to the end against overwhelming odds, had a nobility which made an irresistible appeal to those - such as John O’Leary [... ] - who saw the issue primarily in terms of the ancient struggle against England; to others, like Yeats, whose piety and indignation were stirred by the spectacle of greatness overthrown by mediocrity; and to such as Joyce, for whom the fall of Parnell symbolised the triumph of all that was […] degrading in Irish life.’ (Lyons, The Fall of Parnell 1890-91 (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1960), p.309. Cited in James Fairhall, James Joyce and The Question of History (CUP 1993), p.128.

R. F. Foster, ‘He was equivocal by nature - especially in his rhetorical relationship with extremism. Parnell’s supposed Fenian connection was really a triumph of language, especially on American platforms; at home he achieved a highly political use of silence. While his record as a leader was ostensibly restrained, except at times of crises, a personality cult developed round him greater than that around any other Irish leader. Inevitably there was a hollowness at the centre. [... &c.]’ (Foster, Modern Ireland, pp.401-2; cited by Michael Valdez Moses, ‘Dracula, Parnell, and the Troubled Dreams of Nationhood’, in Journal X: A Journal in culture and Criticism, 2, 1 Autumn 1997, p.104; ftn. 4.) Quotes Conor Cruise O’Brien on ‘a system in which the emotional “residues” of historical tradition and suppressed rebellion could be enlisted in the service of parliamentary “combinations” of a strictly rational and realistic character [and] the ambiguity of the system must be crystallised in terms of personality.’ (Foster, idem.)

James Fairhall, James Joyce and The Question of History (Cambridge UP 1993), for a succinct account of the Parnell split, ‘Parnell and Irish Politics’, sect. of chp. 4, - viz. Emmet Larkin [The Roman Catholic Church in Ireland and the Fall of Parnell 1888-1891 (Chapel Hill: N. Carolina UP 1979)] sees Parnell as the architect of the modern Irish State, which he created between 1878 and 1886 on the foundation of two political alliances. The first was the Clerical-Nationalist alliance, on which Parnell’s state depended for stability. The second was the Liberal-Nationalist allience, which Parnell need to translate ‘his de facto state from reality to legality’. When conflict arose [in the divorce and Split], Irish nationalists had to choose between these alliances and the man who fashioned them. (p.132.)

Note: In Committee Room 15, John Redmond said, ‘If we are asked to sell our leader to preserve an alliance ... we are bound to enquire what we are getting for the price we are paying.’ Parnell interjected, ‘Don’t sell me for nothing ... If you get my value, you may change me to-morrow.’ This becomes, in James Joyce, ‘Get my price!’ Fairhall, op. cit., p.138.)

D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (London: Routledge 1982; 1991 Edn.), ‘[between 1877 and 1885] Parnellism carried Parnell to power and near-success; after 1886 Parnell disentangled himself from Parnellism with relief, and committed all to the Liberal alliance. When this alliance broke his leadership of the party in 1890, he sought to save his position by playing upon the sentiments that had helped him to power in the first place, and directing them against the Liberal alliance. But the party and the country would not follow him; they shared his emotions, but disapproved of his tactics. It was perhaps tragic, but appropriate, that in 1886 Parnell destroyed Parnellism, and in 1891 Parnellism destroyed Parnell.’ (p.223.)

Further, ‘A true revolutionary movement in Ireland’, Parnell had confessed to an [332] American journalist in 1888, ‘should, in my opinion, partake of both a constitutional and an illegal character’; but the question facing Sinn Féin in 1919, as it had faced Parnell in 1888, was that of finding the most appropriate, and least dangerous, mixture of the two. (Boyce, op. cit., p.332-33.)

[ top ]

Paul Bew, Charles Stewart Parnell (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1980; 1991, ‘Even moderate nationalist opinion - let alone Irish Tories and Liberals - saw Parnell as an extremist … hopelessly entangled in dangerous and speculative projects.’ (p.39; quoted in Michael Valdez Moses, ‘Dracula, Parnell, and the Troubled Dreams of Nationhood’, in Journal X: A Journal in culture and Criticism, Vol., 2, No. 1, Autumn 1997, p.71.)

Note that Moses holds Bew’s biography to argue that Parnell was a ‘conservative … nationalist with a radical tinge’ who hoped to ‘salvage the declining political and economic fortunes of the Ascendancy.’ (Bew, p.136; Moses, p.79.)

S. J. Connolly, ‘Culture, Identity and Tradition: Changing Definitions of Irishness’, in In Search of Ireland: A Cultural Geography of Ireland, ed. Brian Graham (London: Routledge 1997), pp.43-63: ‘The spectacular success of nationalism in supplanting other alignments, across little more than a decade, owed much to Parnell’s political skills. The opportunistic exploitation of the land agitation reflected his ability to combine the politics of the possible with a militant rhetoric in a way that secured him the support of a broad spectrum of opinion, from Catholic bishops and the comfortable middle classes to Fenians and agrarian radicals. But his achievements were made feasible by broader changes in attitudes and ideas. The second half of the nineteenth century saw the development and popularisation of nationalist historical writing, in which the web of changing identities with which we have been concerned was recast as a linear narrative of Irish resistance to English rule. More specifically, the linking of the issues of land and home rule depended on the perfection of a coherent mythology, already beginning to take shape in the Defenderism of almost a century earlier, in which the sixteenth- and seventeenth-century dispossession of the Gaelic and Old English élites was reinterpreted as the dispossession of the Irish people as a whole. This legitimised the claims of the tenant farmer while undermining those of the landlord. The mythology of the Land War of the early 1880s also encouraged a new sense of collective identity. Large and small farmers, the landless and the land-poor, as well as urban groups to whom the farmers’ problems were of no direct concern, were taught to see themselves as united in a joint struggle for lost ancestral rights. In short, the linking of land and home rule created an imaginary community, possessed of a strong sense of collective identity based on historic wrongs and current grievances.’ (p.52.)

Owen Dudley Edwards, review of Robert Kee, The Laurel and the Ivy, in ‘Summer Books’ [with Fortnight 330] (Summer 1994), pp.3-6. The review deals wittily with the development of modern Irish historiography - chiefly revisionism - and with the foregrounding of Irish nationalism in the English conception of Ireland and the Irish (as well as in the self-image of the Irish in England) as a result of Kee’s somewhat over-emphasis of that strand. It also underscore the impact of Bishop Thomas Nulty on Parnell, and postulates that Cpt. O’Shea actually engineered the affair with his wife; further, it presents a psychological portrait of Tim Healy as a kind of homosexual lover of Parnell who ‘destroys the thing he loves’.

[ top ]

Anthony Jordan, review of Frank Callanan, The Parnell Split 1890-91 (Cork UP 1992), with foreword Conor by Cruise O’Brien, 320pp., in Books Ireland (March 1993): study opens of 17 Nov 1890, O’Shea divorce granted; support from Irish Party show three days after; re-elected as leaded eight days after that, on the day of Gladstone’s letter being published; Parnell attacks Gladstone and the Liberals; Tim Healy changes sides; Healy ridicules Parnell and Mrs. O’Shea vitriolically; defeat at bye-election in North Kilkenny, against Michael Davitt’s side; North Sligo defeat, followed by Carlow bye-election defeat in July 1891; left Ireland 28 Sept; died Brighton with his wife by his side, 6 Oct., and buried Glasnevin five days after that. John O’Leary said, ‘in him alone rested all our hopes from constitutional action’; Arthur Griffith said, ‘The era of constitutional politics ended on the day Parnell died’.

Roy Hattersley, reviewing Christy Campbell, Fenian Fire: The British Government Plot to Assassinate Queen Victoria (HarperCollins 2002), writes: ‘None of us finds it easy to be objective about Ireland. And, towards the end of Fenian Fire, I found myself both doubting and resenting Campbell’s judgement that Charles Stewart Parnell was ‘the coping stone in the universal conspiracy’ that killed so many innocent British citizens. Parnell himself was the intended victim of a plot in which the Times printed incriminating letters that it knew to be forgeries. Then the same newspaper, which had followed him for months, revealed his relationship with Mrs O’Shea at the moment that his disgrace was most likely to reduce hopes for Irish Home Rule. As Fenian Fire confirms, there is something abbot Irish independence which both encourages supporters and opponents to advance their respective causes by dirty work. (Guardian Weekly, 6 June 2002., p.17.) See also Keith Jeffery, review of same, in Times Literary Supplement (14 June 2002), p.29,m giving details of the plan to blow up Queen Victoria with assembled dignitaries at thanksgiving service for her Jubilee in Westminster Abbey, June 1887 masterminded by Lord Salisbury; notes that a bomb blew up the recently formed Special Irish Branch unwisely located above a public urinal, in 1884. Cites previous studies, K. R. M. Short, The Dynamite War (1979); Bernard Porter, The Origins of the Vigilant State (1987); Porter, Plots and Paranoia: A History of Political Espionage in Britain, 1790-1988 (1989). Jeffery quotes the last named on the Jubilee Plot: ‘this was probably cooked up by the British agent F. F. Millen, with Jenkinson’s knowledge’, and remarks: ‘this hardly adds up to “a British Government plot”’.

Myles Dungan, ‘Writing Nearly on the Wall for Parnell’, in The Irish Times (13 Feb. 2010), Weekend Review, p.6 - a feature article on the Pigott forgery and espec. the last letter published in The Times (18 April 1887) expressing the view that Thomas H. Burke got his deserts for a life-time of interventions inimical to nationalist interests. Dungan’s article anticipates a lecture that the RIA (25 Feb. 2010) incorporating a partial re-enactment of the Charles Russell’s cross-questioning of Pigott.

Anne Fogarty, ‘The Memory of the Dead: Joyce and the Shade of Parnell’, in Voices on Joyce, ed. Fogarty & Fran O’Rourke (Dublin: UCD Press 2015): ‘[quotes Yeats: ‘The modern literature of Ireland [...] began when Parnell fell from power in 1891 [... &c.]’ - as supra]’: ‘The assertion much-invoked by later historians that culture subsumed the role of politics in the post-Parnell period is here deftly proposed and set up as a neat explanatory principle. But, Yeats’s comments, it must be noted, were made with the benefit of hindsight and are purposefully obscure and contradictory. The death of Parnell is seen as a rupture and yet as galvanising a period of renewal and of the re-consolidation of Irish identiy. Moreover, Yeats intimates that he himself indirectly assumes the mantle of Parnell and that the political energies once orchestrated by the fallen leader find a new outlet in the literary activities of the Revival. The “event” at which Yeats gestures remains determinedly vague. It appears to indicate the founding of the Abbey Theatre in the first instance, but also obliquely encompasses later upheavals of the 1916 Rising and the War of Independence. Parnell hence seems ot act as a guarantor of integrity and continuty for Yeat, qhile yet allowing hi ot construct a malleabe political vocabulary with which he fences with the intricate realities and ideological divisions of early twentieth-century Ireland. / Joyce’s initial assessments of the fall of Parnell are by contrast far less sanguine and conciliatory. Where Yeats implicates Parnell in a narrative of self-renewal, the re-routing of values and of processes of reclamation, Joyce highlights the tragic aspects of the fall of a leader who was once so revered and uses this recognition of mass betrayal as the grounds for excoriating social and political critique. A scornful disregard for populist and constitutional nationalism, moreover, appears to be the overriding lesson that he draws from his contemplation of the political disarray of the 1880s and 1890s. The surviving fragment of Joyce’s lost juvenile poem “Et tu, Brute”, written when he was ony nine years old, denouncing T. M. Healy, Parnell’s opponent in the Irish Parliamentary Party, and seeing him as replicating the treacher of Brutus in his assassination of Caesar, may be seen as typifying the author’s early stance In “Home Rule Comes of Age”, Joyce bitterly condemns the Irish Parliamentary Party for selling Parnell to the “English Dissenters” without exacting the 30 pieces of silver that would have fully underscored their Judas-like role. In this and other Triestine journalistic pieces, Joyce identifies with Parnell, casting him as a victim or outcast and uses his anger and devotion to the lost cause of Parnellism as points of leverage against the debased politics and social values of contemporary Ireland. Loyalty to the deposed leader seems to warrant a supercilious stance that sets the author apart from his fellow country people and forces him into the role of satirist and moral scourge. Yet, it also provides the grounds from which Ireland can be critiqued from within and a different future in the wake of Parnell can be envisages. Even though “The Shade of Parnell” (1912) repeats and even magnifies the lacerating insight of the earlier disquisition on Home Rule in asserting that the Irish did not throw Parnell “to the wolves: they tore him apart themselves”, it begins to construe his fateful death not as a tragic endpoint but rather as part of a cycle of renewal. The central trope of the essay casts Parnell as an unappeased Shakespearean ghost but the final lines gloss this image not as a vengeful revenant - “it will not be a vindictive shade” - but rather as a monitory presence and an inelectuable aspect of the natonal condition that refuses to be suppressed. The lingering spectral presence of Parnell become a means of ensuring that more radical forms of freedom and more untrammelled modes of identity might emerge in the country. Ultimately, then, Joyce in his non-fictional conjurations of Parnell exploits the ambiguity and opposing facets of his legacy: on the one hand, the ousted leader as a sign of guilt, lack and failure, while, on the other hand, he betokens power, froideur, indomitability and the unrealised promise of nationalist ideals. As will become evident,, Joyce’s fictional works make even further play with these countervailing aspects of the myth of Parnell and fruitfully expand them while never relinquishing the primary insights so starkly laid forth in his journalism. Although the fervour of Joyce’s Parnellism never abates, it is capable of taking on a number of guises.’ (pp.39-40.)

Note: Fogarty goes on to criticise the common assumption that Joyce’s view of Parnell was "fixed and invariable" and not responsive to ‘further developments on the Irish political scene.’ (Ibid., p.41.) Further, she characterises the revisionist biographies by F. S. Lyons, Conor Cruise O’Brien, R. F. Foster, Paul Bew, and Frank Callanan each according as they ‘disentangle the man from the myth’ (p.42) and identifies Joyce’s polysemous relation to Parnell as "symbol of legitimacy, national identity, sovereignty", but also as a "symptom" - after Slavoj Žižek - ‘the defective father figure or a lack in the symbolic order’. (here p.44.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Speeches - 1: ‘Show the landlords that you intend to hold a firm grip on your homesteads and lands. You must not allow yourselves to be dispossessed as you were dispossessed in 1847.’ (Westport, 1 June, 1879); ‘Not one cent of the money contributed and handed to us will go towards organising an armed rebellion in Ireland’ (New York, Jan. 1880.)Speeches - 2: ‘None of us, whether we be in America or Ireland or wherever we may be, will be satisfied until we have destroyed the last link which keeps Ireland bound to England’ (Cincinnati, Jan. 1880; Parnell to Pearse: Some Recollections and Reflections, Dublin: Browne & Nolan 1948, p.17.)

Speeches - 3: ‘We cannot, under the British constitution, ask for less than the restitution of Grattan’s parliament, with its important privileges and wide far-reaching constitution. We cannot, under the British constitution, ask for more than the restitution of Grattan’s parliament. But no man has the right to say [to his country], “thus far shalt thou go and no further”; and we have never attempted to fix the ne plus ultra to the progress of Ireland’s nationalhood, and we never shall’ (Jan. 1885, Cork; quoted in Parnell to Pearse: Some Recollections and Reflections, Dublin: Browne & Nolan 1948, p.28.)

Speeches - 3 [on Boycotting - I]: ‘I think I heard somebody say “Shoot him!” - (loud cries of “quite right too” with renewed applause) but I wish to point out to you a very much better way - a more Christian, and a more charitable way, which will give the lost sinner an opportunity of repenting. When a man takes a farm from which another has been evicted, you must show him on the roadside, when you meet him, you must show him in the streets of the town, you must show him in the fair and the market place, and even in the place of worship, by leaving him severely alone - putting him into a kind of moral Coventry, isolating him from his kind like the leper of old - you must show him your detestation of the crime he has committed. And you may depend upon it, that there is no man so full of avarice, so lost to shame, as to dare the public opinion of all right thinking men, and to transgress your unwritten code of laws.’(10 Sept. 1880; quoted in Peter Berresford Ellis, A History of the Irish Working Class [1972] London: Pluto 1996 edn., p.138.)

Speeches - 4 [on Boycotting - II]: ‘Keep a firm grip on your homestead [and use] the strong force of public opinion to deter any unjust men amongst you … from bidding for such farms.’ Parnell dissuaded Land League members from violence and recommended a ‘very much better way - a more Christian and charitable way’ of restraining than murder - placetakers must be shunned ‘as if if her were a leper of old.’ (Quoted in D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, London 1982, p.210.)

Speeches - 5 (Belfast in 1891): ‘I have to say this, that it is the duty of the majority to leave no stone unturned, no means unused, to conciliate the reasonable or unreasonable prejudices of the minority. I think the majority have always been inclined to go a long way in this direction; but it has undoubtedly been true that every Irish patriot has always recognised ... from the time of Wolfe Tone until now that until the religious prejudices of the minority, whether reasonable or unreasonable, are conciliated ... Ireland can never be united; and until Ireland is practically united, so long as there is this important minority who consider, rightly or wrongly - I believe and feel sure wrongly - that the concession of legitimate freedom to Ireland means harm and damage to them, either to their spiritual or their temporal interests, the work of building up an independent Ireland will have upon it a fatal clog and a fatal drag.’ (Quoted by Paul Bew, in Fortnightly Review, October 1991.)

Speeches - 6 (Wolverhampton, q.d.): Parnell spoke about the ‘sacred ties’ between England and Ireland, a phrase and notion which John Redmond was to describe as the very ‘theory of Home Rule.’ (Quoted by Paul Bew, in Fortnightly Review, Oct. 1991; see also Bew, Charles Stewart Parnell, Dublin: Gill & Macmillan, 1991, 152pp.)

[ top ]

References

Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (Washington: Catholic Univ. of America 1904), gives extract from Address to the House of Representatives, Washington.Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2. The the chief works containing significant testimonies on Parnell cited or sampled are by R. Barry O’Brien, T. P. O’Connor, Timothy Healy, Frank Hugh O’Donnell, and William O’Brien; Vol. 2, selects Words of the Dead Chief (1892) [303-12]; ‘To The People of Ireland’, the manifesto of 29 Nov 1890 [312-15]; approx. 45 REFS & REMS; BIOG, 369, & COMM [under the caption Parnellism], 366. FDA3 adds some 35 REFS & REMS. in addition to a bio-biographical section on Parnell, FDA2, 366 has a section on Parnellism with a select general bibliography that includes, CC O’Brien, Parnell and His Party 1880-90 (Oxford 1957). [Bibl. as supra.]

James Joyce Library: held in his Trieste library copies of The Life of Charles Stewart Parnell (London & Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson [1910]); R. J. O’Duffy, Historic Graves in Glasnevin Cemetery (Dublin: James Duffy 1915); and Words of the Dead Chief, compiled by Jennie Wyse-Power (Dublin: Sealy, Bryers & Walker 1892). (See Richard Ellmann, The Consciousness of James Joyce, Faber, p.122 [Appendix].

Hyland Books: Catalogue No. 214 lists Henry Parnell, On Official Reform (1969 facs. of 1831 3rd ed.); H. Harrison, Parnell Vindicated: A Lifting of the Veil (1931); Alfred Robbins, Parnell, the Last Five Years Told from Within (1926). Catalogue No 224 lists Dorothy Eden, Never Call it Loving (London 1966), fictional biography of Kitty O’Shea [Cathach Cat. 12]; The Repeal of the Union Conspiracy, or Mr Parnell, MP and the IRB (1st ed. 1886), 92pp. [Carty 1472]; H. O. Arthur Forster, ‘Guilty or Not Guilty?’, or The Opinions of Eminent Liberals with Regard to the Parnellite Party [1883], 8pp.

Belfast Linenhall Library holds The Parnell Movement, T. P. O’Connor; F. H. O’Donnell, The Lost Hat, the clergy, the collection, the hidden life [n.d.; also n.d. in Belfast Central Public Library].

[ top ]

Notes

Arthur Griffith, ‘The era of constitutional politics ended on the day Parnell died’, and W. B. Yeats, “The Death of Parnell”, in Autobiographies (1955).W. B. Yeats: According to Joseph Holloway, Yeats said on 26 April 1905 that he had Charles Stewart Parnell in his mind when he wrote On Baile’s Strand : ‘People who do aught for Ireland […] ever and always have to fight with the waves in the end.’ (Holloway’s Journal ; quoted in Richard Allen Cave, ed., W. B. Yeats: Selected Plays, Penguin Edn. 1997, “Commentaries & Notes” [The Green Helmet ], p.300.

Boundaries (& Job): When Parnell said, ‘No man has the right to set a boundary to the march of a nation and to say ne plus ultra, thus far shalt thou go and no further’ - his famous answer to the Fenians delivered in Cork (Jan. 1885), he was ultimately echoing the Book of Job: ‘Where were you when I stopped I planned the earth? Tell me, if you are wise, do you know who took its dimensions? / ... Were you there as I stopped the waters / as they issued gushing from the womb? / When I wrapped the oceans in clouds / and swaddled the seas in shadows? / and when I closed it with barriers / and set its boundaries, saying, “Here shalt thou come but no farther, / here shalt your proud waves break?”’ (Job, 38:4-9.)

Hesitency: Parnell’s supposed letter from Kilmainham to Patrick Egan contained the phrase, ‘Let there be an end to this hesitency [sic]. Prompt action is called for […].’ (See Robert Kee, The Laurel and the Ivy, Penguin 1993, p.228; quoted in Niamh O’Sullivan, Joyce: The Spiritual Liberator, BA Diss., UUC 2000.) See also under Richard Piggott q.v., - author of the forged letter.

Kitty O’Shea (1): Katharine O’Shea was left the equivalent of seven million pounds in today’s money in 1889 at the death of an aunt; she later wrote wrote a 2 vol. Charles Stewart Parnell, his love story and political life (publ. 1914).

Kitty O’Shea (2) Katherine O’Shea cited her own sister Anna Steele with whom she was locked in a probate quarrel as co-respondent in her return of charges of adultery against her husband, knowing her to have had several affairs.

Kitty O’Shea (3) - properly Kate to self and family - is buried in Littlehampton Cemetery, Sussex, under a Celtic cross inscribed ‘To the beloved memory of / Catherine / widow of Charles Stewart Parnell [...]’ She bore three children by him while still married to O’Shea, an possibly another still-born after her marriage to Parnell.

‘Phoenix Park Murders’: The assassination of Thomas Burke (Permanent Under-Secretary) and Lord Frederick Cavendish (Irish Chief Sec. for Ireland) - who happened to be accompanying the other for an evening walk at the time (7.30 p.m.) - was perpetrated in the Park on 6 May 1882 by members of the Irish National Invincibles, a Fenian splinter group. The assassins, Tim Kelly and Joe Brady, had targeted Burke as a perceived traitor and a so-called “Castle Catholic”, though Burke, a graduate of Royal College, Galway, was responsible for the introduction of the Intermediate Examination awards an numerous educational improvements. Kelly struck and Burke and Brady at Cavendish. The killers used surgical knives purchased for the purpose while the victims unsuccessfully defended themselves with umbrellas - details that lent added horror to the event. Superintendent Mallon of the “G” Division organised the manhunt, arresting numerous suspects on 13 Jan. 1883 - among them James Carey and Michael Kavanagh, both of whom supplied information about the crime. (Carey - who was a builder - pointed out Burke while the latter acted as get-away driver.) Cary agreed to testify against the assassins, who were hanged on his evidence together with Michael Fagan, Thomas Caffrey, Dan Curley, all found to be materially involved in the assassination - all between 14 May and 4 June 1883. The hangman was one William Marwood. James Fitzharris (known as “Skin the Goat”) acted as driver for the assassins and served 15 years in prison (d.1910) during which he revealed no information about the plot or his associates. (There is a bronze grave plaque to him, citing also the men who were hanged but also Joseph Poole, as having “died for Ireland”.) Members of the founding executive, John Walsh, Patrick Egan, John Sheridan, Frank Byrne, and Patrick Tynan escaped trial and later were well-received by Irish-Americans. While travelling under the alias of Power, Carey himself was shot dead by Patrick O’Donnell of Donegal on board the Melrose Castle off Cape Town, South Africa, on 29 July 1883. O’Donnell was brought back to London, convicted of murder at the Old Bailey and hanged on 17 Dec. 1883. [See “Irish National Invincibles” Wikipedia page with “Skin the Goat” plaque - online.]

James Joyce: References to the Phoenix Park Murder permeated Joyce’s Ulysses, but notably the “Eumaeus” chapter where the character called “Skin the Goat” is falsely supposed to be a denizen of the cabmen’s shelter. Early on, in All Hallows Church, Westland Row, Bloom mistakenly cites Peter Carey, the brother of the betrayer, when he reflects ‘That fellow that turned Queen’s evidence on the invincibles he used to receive communion every morning. This very church. And plotting that murder all the time’ (81:26-28). (Later the Invincibles are called ‘the Denzill Lane boys“ in reference to the address where many of them lived - a street adjacent to the church here mentioned: 424:26.) The “Aeolus” chapter contains some erroneous information circulating in the offices of the Freeman’s Journal about the time and location of the murders (136:3-4), together with the identity of the murderers, Kelly and Brady (136:11). Information about the two cab-drivers, Michael Kavanaugh [Kavanagh], and James “Skin-the-Goat” Fitzharris, is also supplied. (136:16). Here the supposed route of the assassins is communicated by means of anagram: “F. A. B. P. X.” (137:5) - though this was actually the rout taken by Fitzharris who carried the main party rather than the killers, and whose itinerary is regarded as a decoy. (137:12) When he hears the phrase ‘give him the whole bloody history’ in the journalists’ conversation, Stephen Dedalus recurs to his earlier conception of history as the ‘[n]ightmare from which you will never awake’ (137:22). Meanwhile we are told that commemorative postcards are being sold at the site of the murders (138:5). Next, in dwelling on Corny Kelleher as a possible betrayer, Bloom harps on Joseph Chamberlain - the supposed instigator of the Boer War - and compares him with Carey, a real betrayer (‘Egging raw youths on to get in the know. All the time drawing secret service pay from the castle’: 163:20-1). Here is reference is patently inaccurate since Carey was not in the pay of the Castle - a detail that better suits the “Sham Squire”, Francis Higgins [q.v.]. A little after, Bloom contemplates the cell-like organisational structure of the Fenians - a structure originated by James Stephens [q.v.]: ‘Circles of ten so a fellow couldn’t round on more than his own ring. Sinn Fein’ (163:36). In the “Cyclops” episode, a cadenza on the behaviour of the penis of the hanged man is specifically related to Joe Brady (304:30), and this provides the pretext for a political intervention on the part of the Citizen (Michael Cusack): “So of course the citizen was only waiting for the wink of the word and he starts gassing out of him about the invincibles and the old guard [ …]" (305:11). In the “Eumaeus” episode, “Skin the Goat” [Fitzharris] is identified with the pig-keeper in the Odyssey (621:37). The facts of the murders are then revisited - again erroneously (629:7) since Bloom get the year wrong in the telling (629:28). This takes place in the context of Bloom’s colloquy with the sailor Murphy off the Rosevean, and leads on to his remarks about “Skin-the-Goat” and the character of the plot as a ‘confidence trick ... prearranged’ (640:1). Finally, he forms the conclusion that conspiracies are best avoided in Ireland on the “offchance of a Dannyman coming forward and turning Queen’s evidence’ (640:8) - a reflection of Joyce’s own conviction that a traitor is never lacking in Ireland. [The information for this note is substantially gleaned from the Invincibles page of Jesse LeRoy Mabus at Evergreen Academic Computing - online; accessed 12.07.2012.]

John Woulfe Flanagan (1852-1929), the eldest son of Stephen Woulfe Flanagan, PC, a judge of the landed estate court and owner of 3,500 acres in Sligo and Roscommon (with an estate at Rathfudy); m. Mary Deborah, dg. of John Richard Corballis, QC; ed. Oscott and Balliol Coll., Oxford; grad. double-first in classics; English bar, 1877; high-sherriff of Roscommon, 1881; appt. to staff at the London Times, 1886; became main-player in the newspaper’s campaign against Parnell and wrote the articles entitled “Parnellism and Crime”, though exonerated from blame in regard to the acceptance and publication of the “Parnell letters” - i.e., Pigott’s forgeries - by his obituarist; chief leader-writer for the Times in 1916, when he dismissed the insurgents as pro-German; m. Maria Emily, dg. of Maj. Gen. Sir Justin Sheil, 1880; children John Henry and Jane Mary; d. 16 Nov. 1929, at home, 31 Tedworth Sq., Chelsea. (See Dictionary of Irish Biography, RIA 2004.) Note that the Woulfe-Flanagan home in Dublin is now part of Belfield campus of UCD.

Captain O’shea (DNB) Wiliam Henry O’Shea (1840–1905), Irish politician, born in 1840, was only son of Henry O’Shea of Dublin by his wife Catharine, daughter of Edward Craneach Quinlan of Rosana, co. Tipperary. His parents were Roman catholics. Educated at St. Mary’s College, Oscott, and at Trinity College, Dublin, he entered the 18th hussars as cornet in 1858, retiring as captain in 1862. On 24 Jan. 1867 he married Katharine, sixth and youngest daughter of the Rev. Sir John Page Wood, second baronet, of Rivenhall Place, Essex, and sister of Sir Evelyn Wood. In 1880 O’Shea was introduced by The O’Gorman Mahon [q. v.] to Parnell, who shortly afterwards made the acquaintance of Mrs. O’Shea. Suspicions of an undesirable intimacy between them caused O’Shea in 1881 to challenge Parnell to a duel. His fears however were allayed by his wife. Meanwhile in April 1880 O’Shea had been elected M.P. for county Clare, professedly as a home ruler. But his friendly relations with prominent English liberals caused him to be distrusted as a ’whig’ by more thorough-going nationalists. In Oct. 1881 the Irish Land League agitation reached a climax in the imprisonment of Parnell and others as ’suspects’ in Kilmainham gaol, and in April 1882 O’Shea, at Parnell’s request, interviewed, on his behalf, Gladstone, Mr. Joseph Chamberlain, and other leading members of the government, arranging what has since been called the ’Kilmainham Treaty.’ The basis of the “treaty” was an undertaking on Parnell’s part, if and when released, to discourage lawlessness in Ireland in return for the promise of a government bill which would stop the eviction of Irish peasants for arrears of rent. This arrangement was opposed by William Edward Forster, the Irish secretary, who resigned in consequence, and it ultimately broke down. In 1884 O’Shea tried without success to arrange with Mr. Chamberlain a more workable compromise between the government and Parnell, with whom O’Shea’s social relations remained close.

At the general election in Nov. 1885 O’Shea stood as a liberal without success for the Exchange division of Liverpool. Almost immediately afterwards, in Feb. 1886, he was nominated by Parnell for Galway, where a vacancy occurred through the retirement of Mr. T. P. O’Connor, who, having been elected for both Galway and the Scotland division of Liverpool, had decided to represent the latter constituency. O’Shea had not gained in popularity with advanced nationalists, and his nomination was strongly opposed by both J. G. Biggar and Mr. T. M. Healy, who hurried to Galway and nominated M. A. Lynch, a local man, in opposition. Biggar telegraphed to Parnell “The O’Sheas will be your ruin,” and in speeches to the people did not conceal his belief that Mrs. O’Shea was Parnell’s mistress. Parnell also went to Galway and he quickly re-established his authority. O’Shea’s rejection, he declared, would be a blow at his own power, which would imperil the chances of home rule. O’Shea was elected by an overwhelming majority (942 to 54), but he gave no pledges on the home rule question. He did not vote on the second reading of Gladstone’s first home rule bill on 7 June 1886, and next day announced his retirement from the representation of Galway. In 1889 he filed a petition for divorce on the ground of his wife’s adultery with Parnell. The case was tried on 15 Nov. 1890. There was no defence, and a decree nisi was granted on 17 Nov. On 25 June 1891 Parnell married Mrs. O’Shea. O’Shea lived during his latter years at Brighton, where he died on 22 April 1905. He had issue one son and two daughters.

Dictionary of National Biography [1912 Supplement] - available online. [ top ]

Curifixes: ‘There were portraits of John Dillon and Michael Davitt hanging in the parlour, and the landlady told me Parnell’s likeness had been with them, until the priest had told her he didn’t think well of her hanging it there. There was on the wall, in a frame, a warrant for the arrest of one of her sons signed by, I think, Lord Cowper, in the days of the Land War …’ (Lady Gregory, Visions and Beliefs, 1920. q.p.)

The Avondale Estate (Co. Wicklow) Howard Parnell, Charles Stewart Parnell: A Memoir by His Brother (NY: Holt 1914) - Appendix on Avondale Estate Avondale is not, as is commonly believed, an old possession of the Parnell family. The ancestral estate is that of Colure in Armagh. The house at Avondale was built by Colonel Hayes, its original proprietor, in 1777, this date being inscribed inside the hall door. Colonel Hayes was a Colonel in the Irish Volunteers during the Irish Rebellion, and the flags of his regiment used to hang up in the hall at Avondale, until, on the death of my brother Charley, they were taken down and placed on his coffin. Colonel Hayes planted a great deal of timber on the estate, and it was through a common interest in forestry that he formed a friendship with Sir John Parnell, the last member of the old Irish House of Commons. This friendship lasted until his death, and was so warm that by his will Colonel Hayes provided that Avondale should pass to his widow if she desired to live there ; but in the case of her not wishing to do so, it was to become the property of his friend. Sir John Parnell, and his heirs. Mrs. Hayes refused to live at Avondale, and so the estate passed to the Parnell family.

The will of Colonel Hayes contained a curious provision that the estate of Avondale should always pass to a younger member of the family (it being considered, no doubt, that the older members would be sufficiently provided for out of the Parnell ancestral estates in the counties of Armagh and Queens); and it also stipulated that the owners of Avondale should take the name of Hayes, or Parnell-Hayes. My grandfather was known as William Parnell-Hayes, but the [303] name Hayes has for some reason been dropped by the subsequent heirs of the property. I came across this will of Colonel Hayes’s in my father’s desk, by accident, after Charley’s death, and it explained to me why my father should have left Avondale to Charley. The latter, I think, never knew about it, because he often expressed regret that the property should have been left to him, as he felt that it ought to have come to me, as the eldest son.

My father only owned the Avondale estate through the generosity of his sister Catherine, the late Mrs. Wigram, to whom my grandfather had left it. My father and Lord Powerscourt were rivals for the hand of Miss Delia Stewart, the American beauty, daughter of Commodore Charles Stewart, and, to enable him to win her, his sister gave him Avondale, in return for a mortgage of £10,000, which was to bring her in an income of £500 a year. My father left Avondale to Charley and an income of £4,000 a year; whilst I was left the old Parnell esta.te in Co. Armagh, with only a small income, because my uncle, Sir Ralph Howard, had given my father to understand that I should be his heir, which would have made me as well provided for as Charley.

—Available online; accessed 23.05.2024 [here reparagraphed]. Keeping the faith: Parnell published a letter in the Freeman’s Journal appealing to the Irish people to have faith in his leadership despite his personal situation; on the following day, Walsh gave an interview with the Central Press Agency in which he said: ‘If the Irish leader would not or could not, give a public assurance that his honour was unsullied, the Party that takes him as a leader can no longer count on the support of the Bishops of Ireland.’ (1 Dec. 1890; Larkin, op. cit., [q.p.]; quoted in Niamh O’Sullivan, “Joyce: The Spiritual Liberator”, BA Diss., UUC 2000.)

House of Parliament: ‘Parnell, on the way to smash up the Freeman’s Journal, stopped the driver of his carriage and pointed silently to the Houses of Parliament on Stephen’s Green which Yeat’s called the noblest edifice in Europe, to extended cheering.’ (Anthony Cronin, “Hearts and Minds”, keynote lecture at the Princess Grace Irish Library Symposium, 2000.)

Tu quoque: ‘In a footnote to his book on Parnell and the Irish Party, Conor Cruise O’Brien writes that when Parnell was cited in the fatal divorce case, the ‘addiction to the tu quoque’ among his supporters ‘would not have helped the cause much either. In a London church when a clergyman at this time condemned Parnell’s moral lapse, an interrupter loudly asked, “What about the Prince of Wales?”’) [See Geoffrey Wheatcroft on O’Brien, in The Guardian (12 July 2003) - online; accessed 12.05.2014.]

Breaking stones: The paving stones on O’Connell St. Bridge were supplied to Dublin Corporation from Parnell’s quarry in Arklow in face of Welsh competition. (See Roy Foster, Paddy and Mr. Punch, 1993, p.57).

Plan of Campaign: note that a novel entitled Plan of Campaign (1881) was issued by an English writer, and historian Frances Mabel Robinson (See Margaret Kelleher, ‘Prose Writing and Drama in English; 1830-1890 [...]’, in Cambridge History of Irish Literature, ed. Kelleher & Philip O’Leary, Cambridge UP 2006, Vol. 1, p.479. See also the reference to the ‘plan of campaign’ against Count Dracula on the first page of Bram Stoker’s eponymous novel (Dracula, 1897).

Portraits, F. S. L. Lyons, John Dillon (1968) incls. a drawing of C. S. Parnell made by J. D. Reigh in 1891, with an MS addition from Parnell himself: ‘That Reigh is the only one who can do justice to my handsome face.’ See also “Parnell” by S. P. Hall, pencil, Nat. Port. Gallery [Anne Crookshank, ed., Irish Portraits Exhibition (Ulster Museum. 1965)]; also an oil portrait by Sydney Prior Hall [signed 1892] in the National Gallery of Ireland, which serves as the cover on F. S. L. Lyons’s life (Charles Stewart Parnell, 1977); a bronze figure of Parnell by Augustus St. Gaudens, on the Parnell Monument, unveiled 1921 [de Breffny, p.215], and made the object of criticism by Arthur Griffith; Sir John Tenniel, cartoon of Parnell as “The Irish Frankenstein”, in Punch, 20 May, 1882 [featuring the monster, watched by a croaching Frankenstein].

[ top ]