|

.jpg) |

|

|

|

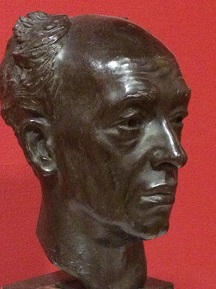

| Oil by Patrick Tuohy | Photo-port (q.d.) | Granger Art (NY) | Bronze (Artist Unknown) | Head by Arthur Power (1914) |

| [ See also portraits ports. by William Rothenstein, Mary Duncan, and Mervyn Peake. There is a photo-series in the National Portrait Gallery (London), with Sir Peter Courtney Quennell, Gilbert Spencer, the Eliots (TS & Vivien), Lady Huxley, Samuel Solomonovich Koteliansky, et al., all taken Lady Otteline Morrell in 1929 - online. ] | ||||

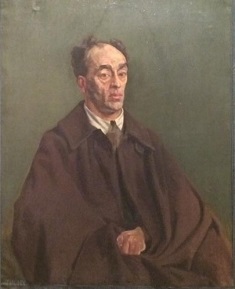

Life

| b. 1880, prob. at Rotunda Mat. Hosp., Dublin; 9 Feb. 1880 [var. 1882 by his own account - poss. to rhme with James Joyce]; son of Francis Stephens and Charlotte [née] Collins, b. circa 1847]; his father, a vanman and stationerís messenger who died two years after his birth [1883 or 1883], after which his mother joined [?remarried] the Collinsí family home, Dublin, 1886; and was henceforth called Mrs Collins]; Stephens was apprehended while begging in the street and committed to the Meath Protestant Industrial School for Boys (Blackrock), 1886-96; ed. with his Collins ‘brothers’ Tom and Dick Collins; competed with them in a team which won the Irish Gymnastics Shield, 1901 - despite his small stature (4’6” [var 4’10”]; affectionately known as “Tiny Tim”; enthralled by tales of military valour in his adoptive family; first worked as clerk in the firm of Wallace (solicitor) and later for Reddington & Sainsbury, (solicitors); published his earliest story, 1905 (‘My life began when I started’ - speaking with his step.dg. Iris; acc. P. McFate); submitted work to Arthur Griffith’s Sinn Féin [journal]- initially without supplying a return address; influenced by Griffith [q.v.], he began to attend Irish classes copnducted by the Gaelic League; |

| he prepared three lectures, on Cromwell and Charles II (1), James II and the Boyne (2), and Douglas Hyde [“the greatest man in Ireland today”] (3), all during 1905; took work as clerk-typist [stenographer] T. T. Mecredy & Son, solicitors, 1906; then living in household of the Kavanaghs, who soon divorced; followed Millicent Gardner Kavanagh from her marriage-home to another lodging, together with her dg. Iris (b. 14 June 1907); made known his marriage to “Cynthia” [prop. Millicent Josephine Gardiner Kavanagh]; contrib. to Irish Worker; in 1907 George [“AE”] Russell [q.v.] read a poem by him in Sinn Féin, seeing in it a ‘spash of genius’, and sought meeting [event retold in George Moore’s Ave]; a son James Naoise, b. 26 Oct. 1909 [d. in an accident, 1937]; issued Insurrections (1909), his first collection of poems - ironically part-sharing a title with his later memoir of the Dublin Rising of 1916 [viz., The Insurrection in Dublin, 1916]; |

| met Thomas MacDonagh [q.v.] in 1910; contrib. “Mary, A Story” to Irish Review (April 1911-Feb. 1912), afterwards issued as The Charwoman’s Daughter (1912), ded. to the Dublin gynecologist Bethel Solomons; wrote The Crock of Gold (1912), mixing whimsy, theosophy, and folk-tale; subject of a long essay by George Russell, 1912; winner of de Polignac Prize, 1914; travelled to Paris on advice of Thomas Bodkin [q.v.], accompanied by Cynthia, 1912-15; wrote Here Are Ladies (1913) in Closerie des Lilas, a Montparnasse café - where he lost and recovered the MS - being a realistic story-sequence in three sections, each inaugurated by poems; mainly treats of ‘the extraordinary debate called marriage’ with the exception of the longest, “There is a Tavern in the Town”, and two others; employs the narratorial voice of a garulous old man akin to that of the Philosopher in The Crock of Gold; published The Demi-Gods (1914), a refinement of the mixed method first seen in The Crock of Gold; learned of post at National Gallery and applied; appointed Registrar, 1915-25 [var. 1924]; left Paris 15 Aug. 1915; became friendly with Edmund Curtis, Osborn Bergin, Richard Best and Stephen MacKenna; studied the Irish Texts Society editions of Irish saga material; |

| issued a diary-account of the Easter Rising as Insurrection in Dublin (1916), first published as extract in The Green Book; in it he writes that the subsequent executions of the leaders on successive days was ‘like watching blood oozing from under a door’ [q.source]; m. Cynthia Kavanagh, London 1919, on the death of her husband; wrote a preface for The Poetical Works of Thomas MacDonagh (1916), at the request of MacDonagh’s widow; engaged in the long-term project of translating of Irish saga material - conceived as an Irish comèdie humaine; issued Irish Fairy Tales (1920) - based on the Fiannaíocht; settled in Kingsbury, London, and worked successfully as a BBC broadcaster, 1922; disturbed by Irish Civil War, Cythnia sends their children to school in England; issued In the Land of Youth (1924), a novel dealing with Maeve’s [Mebhdh] war with the men of Ulster (i.e., the narrative of Táin Bó Cuailgne) - intended as an introduction to his fuller treatment of the Táin by uncompleted through exhaustion; issued his Collected Poems (1926; rev. edn. 1954); undertook the first of several lecture tours to the USA in America under patronage of W.T.H. Howe of Kentucky [Cincinnati; Pres. of the American Book Company]; hospitalised with ill-health - Cornelius Sullivan (a stockbrocker) covering the cost of his return to Ireland; |

| met James Joyce [q.v.] in Paris, 1927 - learned that Joyce believed they shared a birthday on 2 Feb. 1882; by Stephen’s own account Joyce suggested that Stephens complete “Work in Progress” [Finnegans Wake] if failing eyesight prevented him from doing so himself (“The James Joyce I Knew” [broadcast], in The Listener, 24 Oct. 1940); suffered the loss of his close friends Stephen MacKenna [q.v.] and “AE” Russell in 1934 and 1935; stricken by the freak death of his son Naoise in Dec. 1937 - blows which virtually ended his career as a literary artist [McFate]; visited Romania and met Queen Marie there; resumed broadcasting with BBC, 1941 - and continued with it throughout World War II; declared himself an Englishman on the day that Italy entered the War; move in Gloucestershire with his family during the Blitz and commuted to London for broadcasts; gave more than 70 radio-talks during 1937-50 - on poets and poetry, reminiscences of friends and reading verse; settled in cottage on Cotswolds estate of Sir William Rothenstein [patron]; received British Civil Pension List, 1942; awarded DLitt. from TCD, travelling to Dublin to receive it on a grant from the Royal Bounty Fund; |

| issued A Rhinoceros, Some Ladies, and A Horse (1946), being the sole part of a commissioned autobiography; passed last years in ill-health and depression [‘unreasoned anger’]; underwent several abdominal operations between 1920 and 1948 - presumably related to childhood hunger; passes time in Trafalgar Sq. and bookshops and fends off illness and syncope [fainting]; gave his last broadcast on “Childhood Days: Mogue, or Cows and Kids”, 11 June 1950; d. at home (Eversleigh, London), on St. Stephen’s Day, 26 Dec. 1950; The Crock of Gold went through 46 American editions between 1912 and 1947, incl. 3 special editions for the America forces in WWII; Cynthia survives until 1960; there is a bronze head of Stephens by Arthur Power (1914); Mary Makebelieve was successfully treated as a drama (Dublin Theatre Festival, 1982); his step-daughter Iris was married to Norman Wise [see McFate, Uncoll. Prose, Vol. II - Acknows.]. NCBE DIW DIB DIL OCEL KUN FDA OCIL |

|

|

| [ See James Stephens - “A Chronology” - infra. ] |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry (Collections) | |

|

|

| See also | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Fiction | |

|

|

|

|

| Irish folklore & Mythology | |

|

|

| [ top ] | |

| Drama | |

|

|

| Selected & Collected Edns. | |

|

|

| Miscellaneous | |

|

|

| Correspondence | |

|

|

| Broadcasts | |

A BBC talk on W. B. Yeats (London 1948) - see further under Yeats, as infra. |

|

[ top ]

| Electronic editions | ||||||||

| Ricorso Editions (.htm - .pdf - .doc) | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Internet Editions of the Works at Internet Archive | ||

|

||

| The Gutenberg Project Editions of the Works | ||

|

|

||||

[ top ]

| Bibliographical details |

| The Adventures of Seumus Beg [and] The Rocky Road to Dublin (London: Macmillan 1915), vii, 86pp.; Do. [publ. in NY as The Rocky Road to Dublin; the Adventures of Seumus Beg). [Full-text cop- as attached.] |

| CONTENTS |

|

| Green Branches ((NY: Macmillan Co. 1916), ltd. edn. 500 copies; 32 unnumbered leaves on one side only; see note] octavo [8 “ 3/16 x 5 “11/16 inches; 208x145 mm; Bound in 1922, stamp-signed “A - S 1922” in gilt on rear turn-in. Full dark green levant morocco, covers decoratively tooled in gilt with a framework of flowers and stems surrounding a gilt ruled border which in turn surrounds another gilt border with similar floral tools in the corners and top and lower edges. Spine with five raised bands, decoratively tooled with the same floral design in compartments. Gilt ruled board edges, and wide turn-ins with triple gilt rules and the same gilt flower ornaments in the corners, all edges gilt. Minimal darkening to spine. A very fine example. (Notice by David Brass Rare Books, NY - online; accessed 25.10.2020; see extract[infra], or full-text [attached]. |

| Kings and the Moon (London & NY: Macmillan 1938), vi, 83pp. CONTENTS: I am writer; In the red; To Lar, with a biscuit; Envying Tobias; Paternoster; Student taper; Te Deum; Shall he: wilt thou; Gathering the waters; Bidding the moon; Kings and tanists; For the lion of Judah; Threnos; Flowers of the forest; Theme, with variations; In grey air; Wild dove in wood-wild; Trumpets in woodland; Titan with paramour; That which wakens; Or where guile find; Mighty mother. (Available at Internet Archive - online [lim. preview]; list at COPAC/DISCOVER - online; accessed 09.09.2025.) |

| The Charwoman’s Daughter (London: Macmillan 1912): First serialised as “Mary, Mary” in The Irish Review, ed. Thomas MacDonagh, April 1911-Feb. 1912]; pub. in book-form ass The Charwoman’s Daughter (London: Macmillan 1912), 228pp. The Charwoman’s Daughter (London: Macmillan 1917), 228pp. + 2pp. [listing of Stephens’ works available at date with notices on same]. |

|

| Modern editions incl.: The Charwoman’s Daughter, intro. by Hilary Pyle (Dublin & London: Sceptre Books 1966), 139pp.; Do., intro. by Augustine Martin (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1972), 128pp.; French trans. as Mary Semblant, trans. by Abel Chevalley [Prosateurs étrangers modernes ser.] (Paris: Rieder 1927); The Charwoman’s Daughter [facs. of London 1917] (USA: Andesite Press n.d.) [Creativemedia.io - online]; also available at Gutenberg Project [Aus.] - online. [Note shorter pagination in American editions.] |

|

[ top ]

The Crock of Gold (London: Macmillan [Oct.] 1912), ; new imps. Nov. 1912; Jan. & May, August & Dec. 1913; also 1914, 1916, 1918), [[2], v-[vi], [1], 311, [5]p., 19cm.; Do (London: Macmillan 1922), 298pp., ill. [drawings by Wilfred Jones, some col.]; Do. [Macmillan Facsimile Classic Ser.] (London: Macmillan 1926), [3], v-[vi] 1-311, [1]pp. [227pp.]; Do. [printed by R. & R. Clark, Edinburgh] (NY: Macmillan 1926), [10], 227, [5]p., ill. [with twelve illustrations in colour and decorative headings and tailpieces by Thomas Mackenzie]; Do. (London: Macmillan 1928), v, 311pp.; Do. (NY: Macmillan 1928) [12 ills.; front. facing title, ‘The Philosophers were able to hear each other thinking all day long’ (p.5); Do. (NY: Macmillan [St. Martin’s Press] 1953, 1965), v-311pp.; Do. [facs. of London 1926 Edn.] (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1980, 1995), 227pp.; Do. [a Gollancz ebook] (London: Gateway 2015).

|

Pan edition* |

|

|

|

|

Translations |

|

Note: The Crock of Gold (1912) went through 46 American editions between 1912 and 1947, incl. 3 special editions for use by the America forces in WWII. In America the work was generally read for its Irish folklore without reference to the satirical line of the story. (See Eamon Kelly, review of After the Flood: Irish America, 1945-1960, ed. Matthew J. O’Brien & James Silas Rogers, 2009, in Books Ireland, March 2011, p.49.) |

| [ For extracts, see Quotations - as infra; for plot summary, see Notes - as infra; for full text, see RICORSO Library [as .pdf or as .doc]. |

| Here are Ladies (London: Macmillan 1913), 348pp - Contents: “Women”; “Three Heavy Husbands”; “A Glass of Bee”; “One and One”; “Three Women Who Wept”; “The Triangle”; “The Daisies”; “Three Angry People”; “The Threepenny Piece”; “Brigid”; “Three Young Wives”; “The Horses Mistress”; “Quiet Eyes”; “Three Lovers Who Lost”; “The Blind Man”; “Sweet-Apple”; “Three Happy Places”; “The Moon”; “There Is a Tavern in the Town” (70pp.). [See full-text copy in RICORSO Library > Irish Classics - via index, or attached]. |

The Insurrection in Dublin [1st edn.] (Dublin & London: Maunsel & Company Ltd 1916), xiv+111pp. [also a 2nd impression]; Do. (NY: Macmillan 1916), 148pp. [available at Gutenberg Project - online; Do. [6th edn.] (Dublin: Maunsel & Company Ltd 1917) Do. (NY: The Macmillan Company 1917), 148pp. [American printed; available at Internet Archive - online]; Do. (Dublin & London: Maunsel & Company Ltd 1919). 111pp.; Do. [3rd edn.] (Chicago: Scepter Books 1965). 100pp. [copyright Iris Wyse]; Do [rep. edn.], with an introduction & afterword by John A. Murphy [ facs. of Maunsel Edn of 1916] (Gerrard’s Cross, Bucks.: Colin Smythe 1978; rep. 1992). xxxiv, 116pp., ill. |

|

| Irish Fairy Tales (1920), by James Stephens, ill. by Arthur Rackham (NY: Macmillan 1920), 318pp. CONTENTS: The Story of Tuan Mac Cairill [1923 edn., pp.1-33]; The Boyhood of Fionn; The Birth of Bran; Oisin’s Mother; The Wooing of Becfola; The Little Brawl at Allen; The Carl of the Drab Coat; The Enchanted Cave of Cesh Corran; Mongan’s Frenzy. [Available at Sacred Texts online; accessed 25.10.2010; also at Gutenberg Project online- and see copy in RICORSO - direct or attached; also separately as .doc. and .pdf.]. Do. [facs. of 1924 edn.] (Londo: Godfrey Cave Associates 1979),ill. [16] lvs. of col. pls. & minor illustrations; facs. title page [printed in Hong Kong.] |

[ top ]

| Uncollected Prose of James Stephens, ed. Patricia McFate, 2 vols. (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1983 [Vol. 1 128pp; Vol. II, 71pp. - but notice that the 2 volumes are page-numbered continuously]. | |||

| Vol. 1: 1907-15 | |||

Autobiographical Fragment, pp.5-9; PROSE WRITINGS - UNDATED The Seoinin [i.e., Shoneen/West-Briton], pp.17-20; Builders Pages, pp.20-23; Patriotism and Parochial Politics, pp.23-26; Irish Englishmen pp.26-29; Poetry, pp.29-32; Mrs Maurice M’Quillan, pp.32-36; Tattered Thoughts, pp.37-41; The Insurrection of ’98, pp.47-54; Success, pp.55-58; The Old Philosopher Discourses on the Viceregal Microbe, pp.58-61; The Old Philosopher Discourses on Government. pp.61-64; Imagination, pp.64-67; Irish Idiosyncrasies, pp.67-76; Good and Evil, pp.76-78; On Politeness, pp.78-81; Facts, pp.81-84; A Gaelic League Art Exhibition, pp.84-85; Caricatures, pp.86-87; The Old Philosopher Discourses on Lawyers, pp.87-90; The Populace Mind: I, pp.97-98; The Populace Mind: II; pp.99-101; The Populace Mind: III, pp.102-103; The Populace Mind: IV; pp.104-106; In Shining Armour, pp.106-109; Come Off That Fence!, pp.109-112; Going to Work, pp.112-115; An Essay in Cubes, pp.115-125; The Old Woman’s Money, pp.125-128 [Century Magazine, 90 (May 1915), p.49]. [Available as readable text at Springer - online; accessed 26.09.2020.] |

|||

| Vol 2 - 1916-48 | |||

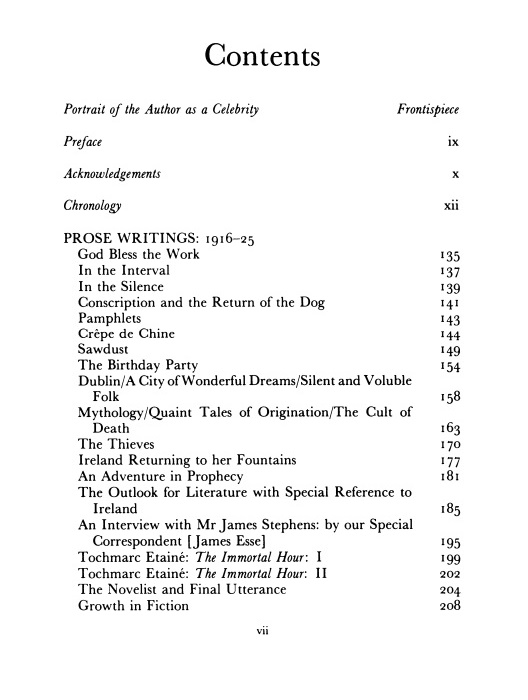

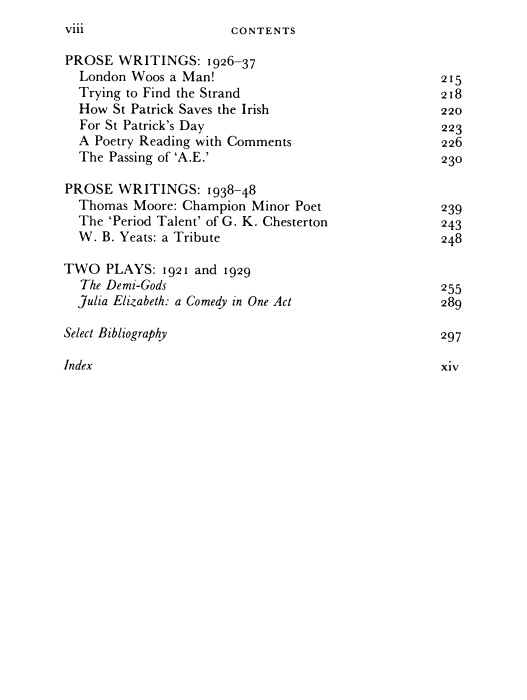

Portrait of the Author as a Celebrity Frontispiece [phot.], ix; Preface [ix]; Acknowledgements [x]; Chronology [xii]. PROSE WRITINGS -1916-25: God Bless the Work [135]; In the Interval [139]; In the Silence [139]; Conscription and the Return of the Dog [141]; Phamphlet [143]; Crèpe de Chine [144]; Sawdust [149]; The Birthday Party [154]; Dublin/A City of Wonderful Dreams/Silent and Voluble Folk [158]; Mythology/Quaint Tales of Origination/The Cult of Death [163]; The Thieves [170]; Ireland Returning to Her Fountains [177]; And Adventure in Prophecy [181]; The Outlook for Literature with Special Reference to Ireland [185]; An Interview with Mr James Stephens by our Special Correspondent [James Esse]; Tochmairc Etaine: The Immortal Hour, I [199]; Tochmairc Etaine: The Immortal Hour, II [202]; The Novelist and Final Utterance [204]]; Growth in Fiction [208]. PROSE WRITINGS - 1926-37: London Woos a Man [215]; Trying to Find the Strand [218]; How St Patrick Saves the Irish [22]; For St Patrick’s Day [223]; A Poetry Reading with Comments [226]; The Passing of “Æ” [230], PROSE WRITINGS - 1938-48: Thomas Moore: Champion Minor Poet [239]; The “Period Talent” of G K. Chesterton [243]; W. B. Yeats: A Tribute [248]. TWO PLAYS, 1921 & 1929: The Demi-Gods: A Play in Three Acts [255]; Julia Elizabeth: A Comedy in One Act [289]; Select Bibliography [ 297]. Includes other titles. [Available at Google Books - online; accessed 04.06.2020; TOC and some pages available at Springer - as download; accessed 26.09.2020.] Note: Many of the individual pieces works are by-lined James Esse. |

|||

| [ TOC page-image ] | |||

|

|

||

|

|||

Mary Makebelieve - the Musical

The Charwoman’s Daughter was produced by the actress Rosaleen Linehan and her journalist husband Fergus Linehan and in a musical stage-version that held the boards and travelled in Ireland during the 1980s and 1990s. Bríd Ní Neachtain played the role of Mary with Linehan as her mother to a score Jim Doherty. It was premiered at Peacock in Oct. 1982 and then went on a seemingly endlessly tour in Ireland. It was successfully revived at the Gate in 1993 and again in April 2016 with a cast of six playing nine roles.

See Arminta Wallace, ‘An Irish Cinderella’, in ‘The Times We Lived In’ [column], in The Irish Times (9 April 2016): It has been called an Irish Cinderella story, but there’s a bit more to James Stephens’s whimsical novel The Charwoman’s Daughter than that. For one thing, it inspired Fergus and Rosaleen Linehan to write a musical, Mary Makebelieve, which was hugely popular in Ireland in the 1980s and 1990s. With an original score by Jim Doherty and a cast that included Barry McGovern and Eileen Reid, it was a show that just kept growing: it premiered at the Peacock in 1982, transferred to the Abbey stage in short order, then toured triumphantly around Ireland. In 1993 there was a new production at the Gate Theatre, which is when our photo was taken. And if this image wouldn’t make you want to get your glad rags on and get yourself to Cavendish Row pretty sharpish, I don’t know what would.

As the teenage Mary, Jacinta Whyte looks as fresh as the proverbial daisy. Her hands rest protectively on the shoulders of her widowed “mammy”, played by Rosaleen Linehan - or maybe she’s holding on because she looks perky and upbeat enough to fly away if not anchored to the stage. The mammy, meanwhile, is dressed in black - actually, not quite black; her blouse has a discreet but definite pattern, and that hat could feasibly take her to Ascot - and wears a smile so slight, regal and knowing, it puts the Mona Lisa into the halfpenny place. See me? she seems to be thinking. If you want to marry my daughter, you’ll have to pass me first.

If there are opening night nerves on the part of either actor, they certainly don’t show. In due course the critics gave the piece their blessing. ‘Fast- moving and very enjoyable,’ wrote Frank Shouldice in The Irish Press. He went on to praise Barry McGovern for his rendition of the comic number “A Policeman in Love” - which is something, I reckon, we’d all pay to see, any day of the week. (Available online; accessed 20.03.2022.)

[See also David O’Grady, review of Mary Makebelieve, in Stage and Screen, 33:12 (Dec. 1982), pp.770-73 - available in JSTOR online [first page only without password; accessed 20.03.2022.]

[ top ]

Criticism| Monographs |

|

| Essays & chapters |

|

|

| Title studies: |

|

| Bibliographies |

|

See references in Richard Ellmann, James Joyce (OUP 1959) [cp.1,930]; introductions to The Charwoman’s Daughter by Hilary Pyle (London: Sceptre Books 1966) and Augustine Martin (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1972). |

Bibliographical details

Birgit Bramsbäck, James Stephens: A Literary and Bibliography Study (Folcroft Lib. Eds. 1973), 209pp., ill. [1p. pl., front.]. Photo port. courtesy Lady Glenavy. CONTENTS: Manuscript material of James Stephens work, except letters; Unpublished letters; Separate publications of James Stephens; Books containing publications by Stephens; Contributions by JS to periodicals and Newspapers; Biography and Criticism; addenda; chronological table of separate publications; lists of newspapers and periodicals; BBC recordings; index. [See extract.]Note: Lady Glenavy, wife of the Free State senator, was formerly Miss Beatrice Elvery and a graduate of the Dublin Metropolitan College of Art.

Patricia McFate, Writings of James Stephens (London: Macmillan; NY: St. Martin’s 1979), xiv, 183pp. [chaps. Stephens: the Man, the Writer, the Enigma [1-22]; The Dance of Life [23-57]; The Quest That Destiny Commands [58]; Make it Sing/Make it New [88 - see extract]; The Art and Craft of Prose [120]; The Marrriage of Contraries [142] Notes and References; Index of works by James Stephens [173]; General Index [178]. (Available at Springer and copied here as pdf; also at Google Books - online; accessed 25.10.2020.)

[ top ]

Commentary

See separate file [ infra ]

Quotations

See separate file [ infra ]

[ top ]

References

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists The Charwoman’s Daughter (1912); The Crock of Gold (1912); Here are Ladies (1913); The Demi-Gods (1914).

NY Public Library (USA) - James Stephens collection of papers, 1908-1939 [bulk 1911-1938]: This is a synthetic collection consisting of manuscripts, typescripts, correspondence, notebooks from 1911 to 1917, financial documents, portraits, and pictorial works. The manuscripts include holograph poems, stories, essays, criticism, and other material, some of which was published in Adventures of Seumas Beg or in his Collected Poems. The typescripts include emended drafts of stories, poems, and miscellaneous notes for works. The correspondence includes letters from the author, dating from 1910 to 1935, to Warren Barton Blake, Thomas Bodkin, Padraic Colum, Baron Dunsany, Lady Gregory, W. T. H. Howe, Sir Edward Howard Marsh, Clement King Shorter, and others. There are also letters relating to the author, dating from 1913 to 1939, between various correspondents including W. T. H. Howe, George William Russell, and others. There are letters to Stephens from Claud Lovat Fraser, James Joyce, Stephen MacKenna, John Masefield, George Moore, George William Russell, May Sarton, and W. B. Yeats, dating from 1916 to [1938]. The bulk of the materials was formerly owned by W. T. H. Howe. There are also materials from Padraic Colum, Crosby Gaige, Sir Edward Howard Marsh, John Quinn, and Anne J. Smith [Annie Smith]. Arranged as MSS and typescripts; Correspondence; Financial Document; and Portraits. (Available at NYPB - online; accessed 26.10.2020.)

Mark Storey, Poetry and Ireland since 1800: A Source Book (1988), pp.178-88, reprints ‘The Outlook for Literature with Special Reference to Ireland’, from Century Magazine (1922).

Georgian Poetry 1911-1912 (The Poetry Bookshop MCMXVIII [1918]), incls. poems by Stephens, viz., ‘In the Poppy Field’; ‘In the Cool of the Evening’; ‘The Lonely God’ [all from The Hill of Vision]. Note: edn. printed by W H Smith with title facing ‘published December, 1912’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects from The Hill of Vision “Light-O’-Love”; from Songs of the Clay, “The Ancient Elf”; from Collected Poems, “The Snare”, “A Glass of Beer”, “I Am a Writer”; also, extracts from The Crock of Gold (Bk. 1, Chap. VII); and Hunger (1918), based on the Lock-Out Strike of 1913. REFS & REMS, 521, 781, 1010, 1023, 1025, 1026, 1220; 1219, BIOG, WORKS & CRIT.

Booksellers & Libraries

Hyland Books (Cat. 214) lists The Crock of Gold [first illustrated edn.] (1922), ill. b Wilfred Jones [Hyland 214]; another edn. 1926, ills. in colour and decorative headings and tailpieces by Thomas Mackenzie; Deirdre, Do., French trans. (1947); another edn. (NY 1970), ills. Nonny Hogrogian

Library of Herbert Bell, Belfast, holds Green Branches (London 1917)); Irish Fairy Tales, ill. Arthur Rackham (London 1920); The Charwoman’s Daughter (London 1912); Where There are Ladies (London 1913); In The Land of Youth (London 1914); The Demi-Gods (London 1914); The Adventures of Seamus Beg (London 1916); The Insurrection in Dublin (Dublin 1916); Insurrections (London 1917); Reincarnations (London 1918); The Hill of Vision (London 1922); Deirdre (London 1923); The Crock of Gold (London 1923); The Crock of Gold (London 1926); Etched in Moonlight (London 1928); The Outcast (London: Faber & Faber, 1929), col. fp. by Althea Willoughby; Strict Joy (London 1931); Kings & The Moon (London 1938).

Belfast Public Library holds Adventures of Seumus Beg (1915); The Charwoman’s Daughter (1912); Collected Poems (1912); Crock of Gold (1913 [Edn.?]); Deirdre (1923); Here Are Ladies (1913); Hill of Vision (1912); Insurrection in Dublin (1919); Irish Fairy Tales (1920); Kings and the Moon (1938); The Outcast (n.d.).

[ top ]

Notes

The Crock of Gold (1912) is an amalgam of existential whimsy, theosophy and folk-tale with a cast of leprechauns, talking animals, the god Angus Óg as well as two philosophers married to the Grey Woman of Dun Goftin and the Thin Woman, ending with a magnificent hosting of the Sidhe. The story begins when Meehawl MacMurrachu’s skinny old cat kills a robin redbreast on the roof one day, thus setting in motion a long and peculiar chain of events since the robin is the particular bird of the Leprecauns of Gort na Gloca Mora, causing them to retaliate by stealing Meehawl’s wife’s washing-board - whereupon Meehawl turns to the Philosopher who lives in the centre of Coilla Doraca (a pine-wood) for advice on how to find it. The chain of events leads on further until Angus Óg, the god, becomes involved and ends up marrying Caitilin, the daughter of a local farmer. Stephens returned to this mythological formula though handling it more effectively in The Demi-Gods (1914). [Notes in part from Fantastic Fiction website, online; accessed 20.08.09.)

W. B. Yeats: Yeats’s personal library, now held in the NLI (Dublin) contains copies of The Hill of Vision (MS 40,568 / 231; O’Shea Cat. 2002: 6 shts); Reincarnations (MS 40,568 / 232; O’Shea Cat. 2004: 2 shts).

| James Stephens and James Joyce |

|

|

Signed “S”: ‘The attribution of “The Greatest Miracle”, signed “S” in the United Irishman (16 Sept. 1905), to Stephens is a canard: Seumas O’Sullivan wrote it and republished it in Essays and Recollections (Dublin: Talbot Press, 1944), pp.141-43.’ (See Vivian Mercier, ‘John Eglinton as Socrates: A Study of “Scylla and Charybdis”’, in James Joyce: An International Perspective, ed. Suheil Bushrui & Bernard Benstock, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1982, p.66, n.)

Austin Clarke reports in A Penny in the Clouds (Chap. 3) that Stephen McKenna ‘taught Irish to James Stephens, and to his enthusiasm and help we owe Reincarnations [1918].’

F. R. Higgins told Austin Clarke how he mistook James Stephens for a bundel of rags in the wind as he walked through Rathgar, drowned in an outsized French cavalry officer’s cloak.

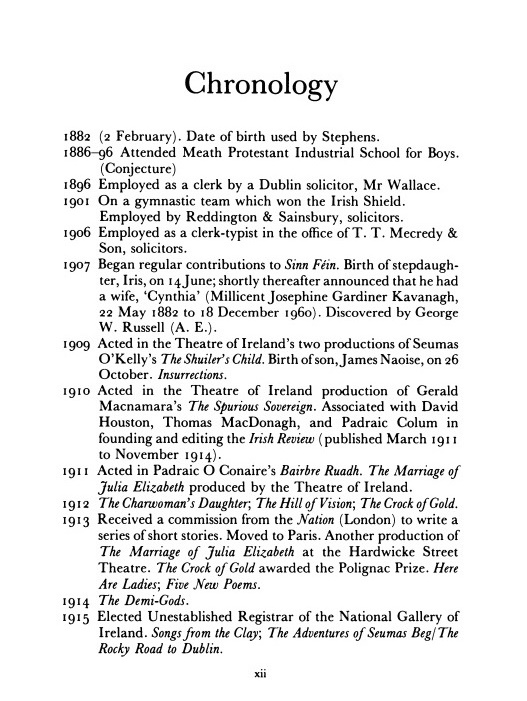

Portraits: oil portrait by Patrick Tuohy, now in the National Gallery of Ireland, shows him in his ‘candle-extinguisher’ coat; an early portrait was made by Estelle Solomons, while a third, by William Rothenstein, is in the possession of Iris Wise, who holds the copyright of his works. Solomons was a neighbour with a studio in the flat above him on Brunswick St. (see Hilary Pyle, Estelle Solomons, Patriot Portrait, 1966). The Rothenstein portrait of Stephens was lent to the Irish Portraits Exhibition in 1965.

[ top ]

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Crosby Gaige: The publisher of Julia Elizabeth is the subject of an article in by Colin Smyth in The Yeats Annual: ‘At Cerf’s suggestion, he [Gaige] had started his publishing house in 1927, asking leading writers to provide him with original works that he could be produced in limited editions, usually signed by their authors whom he paid handsomely. Before the crash in 1929 which wiped out his $5m. fortune, he had produced twenty-two titles, whose authors in order of publication, included Liam O’Flaherty (two books), Siegfried Sassoon, A.E. (George William Russell), Richard Aldington, James Joyce, Humbert Wolfe, Joseph Conrad, Walter de la mare, Carl Sandburg, Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Thomas Hardly, James Stephens, George Moore, and, lastly, W. B. Yeats. / Although Yeats’s The Winding Stair was the last title to be produced by Gaige - the publication programme was taken over by the Fountain Press, distribution continuing through Random House - it was by no means the end of Mr Gaige. Such was the esteem that he was held in by his friends that, following his financial ruin, those who were more fortunate tha he (such as Raoul Fleischmann, owner of The New Yorker, kept him in the manner to which he was accustomed for the rest of his life, and he even produced some further hits, such as Samson Raphaelson’s Accent on Youth (1934,229 performances). While he seemed perpetually short of cash, he never went without the best food and wines [...].’ (Smythe, ‘Crosby Gaige and W. B. Yeats’s The Winding Stair (1929), in Yeats Annual, No 13 (Palgrave Macmillan; 1998), pp.317-28; p.318 [available at Springer - online; accessed 11.10.2020.]

Namesake(s): James Stephens (1825-1901), the Fenian leader or “Head Centre” [q.v.]; also Rev. James Stephens, children’s missioner on the staff of the Church of England Parochial Mission Society, author of Go Forward, from Egypt to Canaan (London 1888), The Coming of Christ and Other Papers, articles formerly in the journal Our Outlook between 1894-1910 (rep. Chelmsford: Solemn Grace Advent Testimony (200?)], and other works incl. The Failure of Christianity: An Address (Torquay 1891), as Minister of Highgate Rd. Chapel, London. [COPAC]

Here Be Poems: A signed copy of Collected Poems of James Stephens (Macmillan 1926) [ltd. edn. 500 large paper copies], 260pp. [ded. “AE”]; is in the possession of Joan Bullock, Enniskillen, Co. Fermanagh - a grand-niece of Shan Bullock, [q.v.].

James Stephens/James Joyce: Colm McCann writes: ‘There is a priceless copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses in the New York Public Library. A first edition. Signed by Joyce to his friend James Stephens. / The collision of book and place is sacred. The library is probably the finest in the world. [...]’ (See McCann, ‘The Home Place: Coming Home’ [contrib.] in The Gathering: Reflections on Ireland (The Irish Hospice Foundation 2013); printed in The Irish Times online - or copy, as attached.

[ top ]