| ‘But if that Countrey of Ireland, whence you lately came, bee of of goodly and commodious a foyle as you report, I wonder that no courfe is taken for the turning thereof to good ufes, and reducing that nation to beter government and civility [... &c.]. (Eudoxus, in View of the State of Ireland, ed. Sir John Ware, 1633.) |

| ‘[The native Irish] being very wilde at first, are now become more civill, when as these [Old English] from their civility are growne to be wilde and meere Irish.’ (View, p.105; quoted in Bradshaw, Hadfield & Maley, eds., Representing Ireland: Literature and the Origins of Conflict, 1534-1660 (Cambridge, 1993) [Maley] p.26.) |

|

||||||

|

| Commodious Ireland |

|

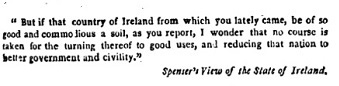

Note that Maturin used a sentence from A View of the Present State of Ireland (1633) as an epigraph on the title-page of The Wild Irish Boy (1808): |

|

| ‘But if that country of Ireland from which you lately came, be of so good and commodious a soil, as you report, I wonder that no course is taken for the turning thereof to good uses, and reducing that nation to a better form of governance.’ (Spenser’s View of the State of Ireland.) |

| [Click here to see the full title-page of The Wild Irish Boy in a separate window.] |

[ top ]

A View of the Present State of Ireland, ed. C. L. Renwick (OUP 1970) - On native Irish histories: ‘[F]or these Irish chronicles as I said unto you being made by unlearned men and writing things according to the appearance of the truth which they conceive do err in the circumstances not in the matter, for all that came out of Spain, they, being no dilligent searchers into the differences of nations, supposed to be Spaniards ans so called them, but the ground work theareof is nevertheless (as I erst said) trewe and certain how ever they thorough ignoraunce disguise the same or through their own vanity whilst they would not seem to be ignorant do thereuppon build and enlarge many forged histories of their own antiquity which they deliver to fools and make them believe them for true. As an example, that first one Gathelus the sonne of Cecrops or Argus who having married the king of Egypt’s daughter thence sailed with her into Spain and there inhabited; then that of Nemed and his four sons who coming out of Scuthia [Scythia] peopled Ireland .. Lastly of the four sons of Milesius king of Spain which conquered that land from the Scythians .. &c.’; pp.1292-1313; orth. sic.)

A View of the Present State of Ireland, ed. C. L. Renwick (OUP 1970) - on the Irish language [Iren.:] ‘I suppose the Chief Cause of bringinge the Irishe language amongest them was speciallye theire fosteringe and marryinge with the Irishe. The which are two most dangerous infeccions for firste the Childe that suckethe the milke of the nurse muste of necessitye learne its firste speache of her, the which beinge the firste that is enured to his tongue is ever after most pleasinge unto him. In so much as thoughe he afterwardes be taughte Englishe yeat the smacke of the first will allwaies abide with him and not onelye of the speche but allsoe of the manners and Condicions for besides that young Children be like Apes which will affecte and imitate what they see done before them speciallye by theire nurses whome they love so well, they moreover drawe into themselves togeather with their sucke even the nature and disposicion of theire nurses for the mind followethe much the Temparature of the bodye and allsoe the wordes are the Image of the mind. So as they procedinge from the minde the minde must be nedes affected with the wordes. So that the speache beinge Irish the harte must nedes be Irish for out of the abundance of the harte the tongue speakethe. The next is marryinge with the Irish which how daugnerous a thinge it is all the Comon wealthes appeare ther to euerye simpleste sence and thoughe some great ones haue perhaps used such matches with theire vassalls and have of them neverthelesse raysed worthie Issue, as Telamon did with Tecmessa, Alexander the greate with Roxane, and Iulius Cesar with Cleopatrie [...]’

A View of the Present State of Ireland, ed. C. L. Renwick (OUP 1970) - on Irish bards [Iren.]: ‘Theare is amongest the Irish a certen kinde of people Called Bardes which are to them in steade of Poets whose profession it is to sett fourthe the praises and dispraises of menne in their Poems or Rymes, the which are hadd in soe high regard and estimation amongest them that none dare displease them for feare to runne into reproch throughe their offence, and to be made infamous in the muthes of all men for the verses are taken upp wit a general applause and usuall songe att all feates and meetings by certeine other persons whose proper function that is whcih also receive for the same great Rewardes and reputation besides.’ [2256-2264].

A View of the Present State of Ireland, ed. C. L. Renwick (OUP 1970) - further on Irish bards [Iren.]: ‘It is most trewe that such poetes as in their wrightinges doe labour to better the manners of men and thoroughe the sweete bayte of theire numbers to steale into the yonge spirites a desire of honour and vertue are worthie to be had in great respecte. But these Irishe Bardes are for the most parte of another minde and so farre from instructinge yonge men in morall discipline that they themselves doe more deserve to be sharpelye discipled for they seldome use to Chose out themselves the doinges of good men for the argumentes of their poems but whome soever they finde moste daungerous and desperate in all partes of disobedience and rebellious disposicion him they set up and glorifye in their rymes him they praise to the people and to yonge men make an example to followe.’ [2279-2290].

A View of the Present State of Ireland, ed. C. L. Renwick (OUP 1970) - further on Irish bards [Iren.]: ‘[Y]ea Truelye I have Cawsed diverse of them to be translated unto me that I mighte underrstande them and surely they savored of swete witt and good invencion but skilled not of the goodlie ornaments of Poetrye yet weare they sprinkled with some prettie flowers of their owne naturall devise which gave good grace and Comlinesse unto them The which it is great pittye to see so abused to the gracinge of wickednes and vice which woulde with good usage serve to beautifye and adorne vertue. This evell Custome therefore nedethe reformacion.’ [2338-2345]. (For longer extracts, see attached.)

Hiberniores ipse Hibernis [referring to the English in Ireland, and speaking of ‘that most daungerous Lethargie’]: ‘Is it possible that anye shoulde so far growe out of frame that they shoulde in so shorte space quite forgette their countrie and theire owne names?’ (View, Gottfried Variorum Ed., p.115; quoted in Andrew Murphy, ‘Gold Lace and a Frozen Snake, Donne, Wotton and the Nine Years War’, in Irish Studies Review, No. 8 (Autumn 1994), p.11.

Unquiete state: ‘Perhaps Almighty God reserveth Ireland in this unquiete state stille, for some secret scourge which shall by her come unto England; it is hard to be knowne, but yet more to be feared’ (View, quoted in Michael Davitt, The Fall of Feudalism in Ireland, 1904, p.3; cited in Chris Morash, ‘Ever Under Some Unnatural Condition: Bram Stoker and the Colonial Fantastic’, in Morash, ed., Literature and the Supernatural, Lilliput 1996, pp.95-117; p.102.)

[ top ]

Keeping out the Scots (1) : ‘Never the more are there two Scotlands, but two kindes of Scots were indeed (as you may gather out of Buchanan), the one Irin, or Irish Scots, the other Albin-Scots; for these Scots are Scythians, arrived (as I said) in the North parts of Ireland, where some of them passed into the next coast of Albine, now called Scotland, which (after much troubled) they possessed, and of themselves named Scotland; but in processe of time (as it is commonly seene) the dominions of the part prevaileth in the whole, for the Irish Scots putting away the name of Scots, were called only Irish, & the Albine Scots, leaving the name of Albine, were called only Scots. There it commeth thence that of some writers, Ireland is called Scotia major, and that which now is called Scotland, Scotia minor. (View, [ed. Renwick?] p.28; quoted in Willy Maley, et al., ‘The Triple Play of Irish History’, Irish Review, in Winter-Spring 1997, p.25.)

Keeping out the Scots (2): ‘For who that is experienced in those parts knoweth not that the Oneales are neerely allyed unto the MacNeales of Scotland [...] Besides all these Scottes are through long continuance intermingled and allyed to all the inhabitants of the north: So as there is no hope that they will ever be wrought to serve faithfully agains their old friends and kinsmen: And though they would, how when they have overthrowne him, and the warres are finished, shall they themselves be put out? Doe we not all know, that the Scottes were the first inhabitants of all the north, and that those which are now called the north Irish, are indeed very Scottes, which challenge the ancient inheritance and dominion of the Countrey, to be their owne anciently: This then were but to leap out of the pan into the fire: For the chiefest caveat and provision in reformation of the north, must be the keep out those Scottes. [79-80; Maley, p.27] Note: Maley also quotes Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, ‘Kelt by kelt shall kithagain with kinagain’ [FW594.3-4] and comments: ‘Spenser’s account of the Scottish roots of Ireland is, like all origin myths, contingent and provisional.’ (p.28).

‘Colin Clout’s Come Home Again’ (on the encounter between Spenser and Ralegh at Doneraile): ‘He piped, I sung: and, when he sung, I piped; By change of turns, each making other merry; / Neither envying other, nor envied, / So piped we, until we both were weary’; [...] gan to cast great liking to my lore, / And great disliking to my luckless lot: / That banished had my self, like wight forlore, / Into that waste where I was quite forgot.’ (Quoted in P. J. Kavanagh, Voices in Ireland, 1994, p.124).

[ top ]