Life

| [sometimes called “Anacreon Moore” in his own day;] b. 28 May, 12 Aungier St., son of John Moore, a Catholic grocer and tea-merchant from Kerry, with premisses as 12 Aungier St., Dublin, and Anastasia Clodd, of Wexford - who was most ambitious for her son (‘Born of Catholic parents, I had come into the world with the slave’s yoke around my neck’); sat on Napper Tandy’s knee at public dinner in 1792; ed. in early childhood by drunken scholar called Malone, who whipped the boys on his arrival, and later at Samuel Whyte Academy, where he acted and wrote (acc. to his Memoir) - and acquired an English accent; tutored in Latin by an usher, Donovan, of patriotic views; profited by learning modern languages from French emigrés at behest of his parents; taught himself to play on the piano purchased for his sister Kathleen, who was also studying harpsichord; contrib. “Lines to Zelia” and “A Pastoral Ballad” to Anthologia Hibernica, 1793; entered TCD, 1794, being admitted under new Catholic Relief Act of 1793 though actually enrolled as a ‘Thomas Moore P[ensionarius] Protestant’ - presum. to secure chance of emoluments; contrib. an Ossianic fragment to The Northern Star (12 May 1797) and The Press (19 Oct. 1797); |

| gregarious and well-liked; and early distinguished for his musical entertainments, sometimes appeared in musical plays with his friends, such as The Poor Soldier of John O’Keeffe, and at one point hoped to become an actor; anonymously publ. a “Letter to the Students of Trinity College” following the recall of Fitzwilliam, 1795; was persuaded by his mother not to make any such political interventions again, and similarly warned off by Robert Emmet, a personal friend - possibly at her request; he did not join United Irishmen subject to examination by Lord Clare [John Fitzgibbon] during the latter’s ‘visit’ to TCD as Att.-Gen., but not required to incriminate others; he was ill in bed at the outbreak of the 1798 Rebellion (acc. to his Memoir) grad. BA 1798; made a translation of the odes of Anacreon, the poet of ribald drinking songs and a favourite from school-days which he read studiously at Marsh’s Library, often being locked in the better to work at night through the good offices of the curator Rev. Thomas Craddock, whose son he knew at college; |

| visited Dr. Kearney, TCD Provost, with his translations; not encouraged to seek a college prize by reason of their ‘amatory and convivial’ subject, but advised by Kearney to publish them as a book (‘the young people will like it’); lent a copy of Spaletti’s edition of Anacreon by Kearney, one of two sent to TCD by the Pope through Archbishop Troy; went to London, 1799 - carrying his money stitched in a waistband, and with scapular and medals secreted in various hems by his mother; entered Middle Temple and overcame initial loneliness; introduced to Lord and Lady Moira by Joseph Atkinson, a former college friend, and embarked on musical entertainments in their circle; published Anacreon (1800) by subscription - with only one from the ‘monkish fellows’ at TCD other than Kearney, to his annoyance; rapidly advanced in London society and counted Mrs. Fitzherbert to his list of subscribers for Anacreon; enjoyed a friendly reception from the Prince of Wales, 4 Aug. 1800, and a subscription; regular visitor to Castle Donington, the Moira’s home in Derbyshire; ‘electrified’ audiences by his drawing-room performances, by his own account; |

| issued The Poetical Works of the late Thomas Little, Esq. (1801), the pseudonym harping on Irish mór (‘big’) and his own diminutive stature; wrote the libretto for The Gipsy Prince, an operetta with music by Michael Kelly which was taken off at Haymarket, July 1802 [1801]; offered the Laureateship of Ireland with a small salary attached by Irish Chief Sec. Wickham, and refused on consideration; appt. Registrar of the naval prize-court [Admiralty] in Bermuda, 1803, his father being appt. to post of Barrack Master in Dublin through influence of of Lord Moira; departed for Bermuda from Spithead on the frigate Phaeton, 25 Sept. 1803; delayed in Virginia till January 1804; dissappointed by income and prospects in Bermuda; sailed to New York on board frigate Boston, whose captain John Douglas proved a generous friend thereafter, April 1804; travelled by coach in N. America as far as Quebec; charmed by Oneida Indians and awed by the Niagara Falls, but found Philadelphia the only place in America that ‘can boast of any literary society’; |

| meanwhile his song “Give Me a Harp of Epic Song” from Anacreon, being set to music by John Stevenson, pleased Lord Hardwicke (Viceroy) so much that the composer was reputedly knighted for it, 1803; Moore returned to England, arriving at Plymouth, 4th Nov. 1804; issued Epistles, Odes, and Other Poems (1806), ded. to Lord Moira and containing pieces reflecting his American experiences, including satires; his juvenalia mauled by Francis [aferwards Lord] Jeffrey in Edinburgh Review as ‘licentious ... propaganda for immorality’; Moore demands a duel which was prevented by the police, resulting in an overnight in Bow St. and some suspicions of foul intent arising from the fact that Jeffrey’s second had been unable to load his pistol, making him appear unarmed - having spent the moments before the duel chatting amiably about literature with his antagonist; approached by William Power, proprietor of a Dublin warehouse, to collaborate with Stevenson with a plan for Irish Melodies - Bunting having declined to collaborate himself but later writing: ‘The beauty of Mr. Moore’s words in a great degree atones for the violence done by the musical arranger to many of the airs which he has adopted’; more recently held to be excessively melancholic and elegiac, in keeping with contemporary notions of the relation of Irish culture to wider Romanticism; |

| Power published a portion of Moore’s prefatory letter in Belfast Commercial Chronicle, 28 May 1807 [substituting April for February in the date line]; 24 songs published in first 2 of 10 folio ‘numbers’, issued together (Dublin 1807; London 1808); all ten vols. - each containing 12 songs except the last, with 14 - were published between 1808-1834 by the Power Bros., James in London and William in Dublin, the latter quickly predominating in importance; contract agreed with the stipulation that Moore would sing them into popularity in London, 1808; played at the Kilkenny Theatricals - an amateur company founded by Richard Power in 1802, and ending in 1819, debuting with the role of David, a Yorkshire yokel in Sheridan’s The Rivals, 22 Oct. 1809; afterwards played as Mungo in The Padlock and Spado in A Castle of Andalusia, a musical piece; and later in the fortnight playing the title-character against the juvenile English actress Elizabeth [“Bessie/Bessy”] Dyke’s Lady Godiva in Peeping Tom of Coventry, 1809; also played his Melologue upon National Music in the entr’acte on two nights; gave vent to his disappointment at the Ministry of All the Talents in “Corruption” and “Intolerance” (1808), and “The Sceptic” (1809), his last political poems in a Popean manner; |

| exited the Kilkenny Theatricals after Oct. 1810; m. Miss Bessie Dyke [aetat. 16], 25 March 1811, and was aspersed by Catholics for marrying a Protestant, though her good sense and loving support were quickly recognised by friends; his sole drama, M.P., or The Blue Stocking, produced at the English Opera House, 4 Sept. 1811; entered into agreement for £500 per annum from the Powers on successful publication of the fourth number of Irish Melodies, 1811; his hopes for a government post dashed when the Prince of Wales, now Regent, back-pedalled on Catholic Emancipation, 1811; frequently contrib. to the Morning Chronicle (ed. Perry) from 1812; arrival of a first child, Barbara (b. Feb. 1812); a second, Olivia (b. March 1813), while the Moores were living at Kegworth near the Moiras; his hopes of a post in India through the patronage of Lord Moira on the latter’s being appointed Governor-General there, were likewise unrealised, 1812-13; Moore accepted the demise of his political expectations with the departure of Lord Moira for India and settled at Mayfield Cottage, nr. Ashbourne, Stafforshire; commenced writing for the Edinburgh Review, notably contributing an article on the Church Fathers, berating their Roman Catholic successors, [1816]; |

| Moore sided with James Power agains the ‘unbrotherly’ conduct of William Power [letter of 1813]; his Intercepted Letters (1813) aimed at the Prince Regent and his ministers, ran to fourteen edns.; suffered loss of a third child, a girl, in early infancy, Spring 1815; visited Dublin and invited to a complimentary banquet on his visit to Dublin, 1815, but declined for reasons explained in a letter to Lady Donegal of July 1815 which speaks of Irish nationalists with disdain; secured advance of £3,000, from Longmans, the highest sum paid for a single poem, for Lalla Rookh: An Oriental Romance (1817) - an exotic and erotic poem (esp. so “The Veiled Prophet of Khorrasan”), which sold out on the first day and ran to six editions within a year; Moore offered to rescind the contract in the prevailing economic conditions after Waterloo, resulting in a year-long postponement [of payment] until the actual date of publication in May 1817; |

| its success put him on an international level with Byron and Scott, being read appreciatively by Goethe, Stendhal (five times), Hugo, Schumann and Stanford; Moore’s his father loses his post as Barrack Master in post-war retrenchments; Moore travelled to Paris with Rogers; suffered the death of his dg. Barbara following a fall, 1817; stayed with family at Donington and briefly at Lady Donegall’s house on Berkeley Square; took up residence at Sloperton Cottage, nr. Devizes, Wiltshire, and close to Lord Lansdowne’s place at Bowood (with its excellent library), Nov. 1817; published The Fudge Family in Paris (1818), an immediate success, amid growing anxiety about the conduct of his deputy in Bermuda whose peculations exposed Moore him to threat of imprisonment; visited Dublin in May 1818, and becomes the object of a public dinner organised by Daniel O’Connell in Dublin, 8 June 1818; a first son was born in Oct. 1818; |

| invited by John Murray to write the life of Sheridan for £1,100 [1K guineas], on the strength of his “Lines on the Death of Sheridan” and commences with research; issued Tom Crib’s Memorial to Congress (1819), replete with ‘flash’ dialect of the boxing establishments; call for payment of the sum of £6,000 resulting from his Bermuda deputy’s defalcation forces him to take legal shelter; contemplates the Liberties of Holyrood, but opts to travel with Lord Russell to Paris, where he remained with his family during Sept. 1819 to 1822, chiefly staying with the family of Martin de Villamil; toured Italy with Lord Russell, meeting Byron at Venice and received his Memoir as a gift; received numerous offers of help including £500 from Lord Jeffrey; his debts to the Admirality reduced to £1,000 by the intervention of Lord Palmerston; the Moores returned to England, April 1822; Moore immediately repays Lansdowne; |

| briefly returned to Paris before settling in England, Nov. 1822; Moore toured the South of Ireland in summer 1823, meeting O’Connell and others to discuss agrarian violence associated with Whiteboys faction and its causes; witnessed ‘for the first time in [his] life, some real specimens of Irish misery and filth; three or four cottages together exhibiting such a naked swarm of wretchedness as never met my eyes before’ (Journal, ed. Wilfrid Dowden, Vol. II, 657; Nolan, ed., Captain Rock [1834] 2008, Intro., p.xvii); issued The Love of Angels (1823), a romantic poem on a subject dramatised by Byron - as he discovered after embarking on it, thus precipitating the publication of his own ‘humble sketch’ thus ‘give myself the chance of what astronomers call an Heliacal rising, before the luminary, in whose light I was to be lost, should appear’; Moore ‘turned his angels from Jews into Turks’ in a revision; |

| issued the Life and Death of Lord Edward [Fitzgerald], based on papers and on memories which he collected in Dublin including many from Major Sirr, whose pistol shot was fatal to him, and said to inaugurate the romantic cult of that aristocratic rebel; first edition of Irish Melodies (1821) appears without Stevenson’s accompaniments, contrary to Moore’s ‘strong objection to this sort of divorce’ (Preface of 4th Edn.); Byron bequeathed his journal to Moore and charged him with writing a life [memoirs] having earlier dedicated The Corsair to him, 1824; Moore was witness to the burning of Byron’s MS in a fireplace at the hands of Byron’s relatives, having lost legal rights to it [var. himself burnt it when faced with opposition from Byron’s relations]; later permitted John Murray to issue his life of Byron as part of the Works, in 17 vols. (1833); travelled in the south of Ireland in 1823 via Kilkenny, visiting Cork, Killarney, Limerick, Roscrea, Dublin, and conversed with Daniel O’Connell en route; left Dublin with Lord & Lady Lansdowne, and stayed at Lismore Castle with the Devonshires (August 1823); sought to confine Bishop’s by-line to ‘revised’ or ‘corrected’ in the publication of single songs; |

| toured the south of Ireland, and witnessed conditions leading to the formation of Shanavests and Rockites, later to inform his novel Memoirs of Captain Rock, The Celebrated Irish Chieftain (1824), particularly occasioned by Rockite disturbances in Limerick in 1821-24 - including the gang-rape of a party of soldiers’ (1st Rifle Brigade) wives and the mass-murder of the Frank family at Bushmills, Co. Cork - which galvanised British interest in Irish affairs; purported to be the manuscript autobiography of the eponymous figure, leader of ‘the poor benighted Irish’, supposedly edited by a Protestant missionary, and much concerned with the extortion of tithes by Protestant ‘Thousands’ from Catholic ‘Millions’; Moore wrote a Life of R. B. Sheridan (1825), out of debt of friendship, and found it condemned by Prince Regent [later George IV] and other close friends of Sherry’s; issued The Epicurean (1827), a novel set in the Roman 2nd century - anticipating Walter Pater’s interest in the subject; issued Travels of an Irish Gentleman in Search of Religion (1833), pseud. “James Barry, Barrister-at-Law”, causing offence to the Anglican establishment in Ireland; attacked on that account in the Dublin University Magazine; |

| offered the support of the Repeal Association for the Limerick seat in Parliament, and turned it down on practical considerations, 1832; involved in a dispute with Power about monies, especially connected with his long outstanding debts to the publisher and the charges made for payment of Bishop’s accompaniments, 1832-33; made triumphant visit to Dublin, 1835; estranged from James Power by other publishers’’ offers, 1832-33; his History of Ireland (4 vols., 1835-46), orig. contracted with Longmans for 3-vols in a series including Walter Scott and James Macintosh [i.e., Lardner’s Cabinet Encyclopaedia] and later extended to 4 vols., Aug. 1837; the initial volume was not well-received by Irish critics of either camp and the whole accomplished at great cost to defray his legal expenses; death of Stevenson, 1833; death of Power 1836 [see Notes from the Letters of Thomas Moore ... &c. 1853, intro. letter by T. C. Croker]; issued Collected Poems (1841), selected by himself with a prefatory acknowledgement to Edward Bunting; reviewed ‘[Henry] O’Brien’s Round Towers of Ireland’ (Edin. Review, Apr. 1834, p.143) and incurred a satirical riposte from Fr Prout [Sylvester Mahony], as “The Rogueries of Thomas Moore” (Fraser’s Magazine, 1835); visited Ireland in 1838 and became acquainted with the Orientialist-Irish controversy chiefly between Sir William Betham and George Petrie, and was gained access to RIA Library, sponsored by J. H. Todd [q.v.]; deeply by the MSS Collection and admitted the ignorance expressed in his History of Ireland (vol. 1, 1834), acc. to Eugene O’Curry, then involved in cataloguing it; |

| Moore suffered the death of five children, of whom John Russell Moore (named after the British premier, later his biographer) joined the army and died of tuberculosis at home; Anastasia, a dg., fell down stairs and died shortly after, while young Tom joined the Foreign Legion and died in Africa in 1846, causing Moore to write in his journal: ‘we are left alone! Not a single relative have I now left in the world!’; he suffered mental illness and depression following a stroke which incapacitated him as a performer; passed last years in premature senility (poss. Alzheimer’s - “dead to the world”, acc. T. C. Croker); d. Sloperton Cottage, [Bromham parish], nr. Devizes, Wiltshire 25 Feb. 1852; bur. at St. Nicholas’ Church, Bromham, under a modern Celtic Cross with elaborately ornate panels and an inscription from Byron: ‘The poet of all circles and idol of his own’; survived by wife (d.1867); his mother outlived him by 13 years and presented his library to the RIA. F |

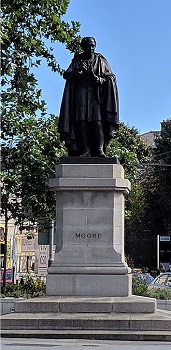

| his international standing advanced by Augustin Thierry’s Dix ans d’études historiques (1835), narrating the blight of Irish history in the spirit of Moore; his Memoirs, Journals, and Correspondence (8 vols., 1853-56) were issued by his literary executor Lord John Russell, and immediately subject to criticism for the chronological curtailment of the material and the unselective approach to personal remarks in Moore’s original documents; some 1,200 letters by Moore were dispersed by sale shortly after; his reputation suffered an eclipse among Irish nationalists from Thomas Davis onwards, being increasingly ridiculed for his insistence on ‘the tear and the smile’ as Ireland’s trademark (see note); a model for a memorial statue to be located at the corner of College Green (i.e., College Street) was prepared by John Hogan, but rejected - much to the dismay of William Carleton - in favour of another by Christopher Moore, in place today, which was ridiculed on account of its location over a public urinal (“the meeting of the waters”); the statue was called ‘that horrible exportation from London’ and a ‘hideous caricature of our national bard’ by The Irish Builder; |

| more recently rehabilated with moderate praises for the poems especially in view of their coded negotiation of Union politics and a new enthusiam for Captain Rock in its character as a quasi-novelistic critique of British policy in Ireland (reiss. 2008); he bequeathed his library to RIA (Dublin); his “The Last Rose of Summer”, composed in 1805 and set to music by Sir John Stevenson for Irish Melodies (1807 [first] ser.), was later made the subject of variations by Beethoven for the Scottish publisher George Thomson in c.1815; copyright to Irish Melodies came to Power’s widow at his death in 1836, and afterwards passed by her will to her unmarried dgs.; William Hazlitt incls. an essay on Moore and Leigh Hunt in his Spirit of the Age (1825); the article on Moore in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA 2009) is by Harry White, MRIA; Moore’s personal library is held in the Royal Academy of Ireland [RIA]; Una Hunt pianist and broadcaster, is a leading interpreter and anthologist of his musical lyrics. ODNB PI JMC NCBE DIW DIB DIH DIL OCEL MKA RAF ODQ FDA OCIL [RIA] |

| [ See also “Thomas Moore” by Harry White in the Dictionary of irish Biography (RIA 2009) - online. ] |

[ top ]

|

|

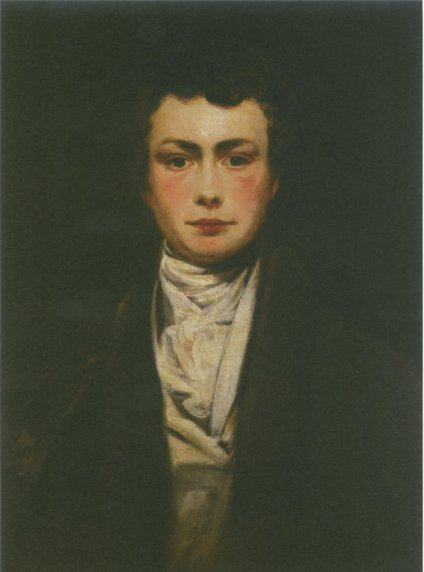

| Moore by Sir Martin Shee | Moore by Sir Thomas Lawrence |

[ top ]

|

||

| Moore’s Memorial Statue by Christopher Moore, in College Street, Dublin (erected 1857) | ||

| The statue at the juncture of Westmoreland St. and College St. was an object of derision for William Carleton and James Joyce and a source of perennial amusement for Dubliners—not least because a men’s toilet was built under it, which local wits and Joyce himself facetiously dubbed “The Meeting of the Waters” after the poem in Irish Melodies of that name. The public convenience was closed in recent times by reason of public security in the age of drug-trafficking and the statue and plinth themselves removed fro refurbishing works, shortly to be reseated in 2023. It appears in both A Portrait of the Artist (1916) and in Ulysses (1922) and is the subject of very different reflections by Stephen and by Bloom. ... | ||

| See also remarks on Moore and Joyce in Harry White, ‘The Auditory Imagination of Thomas Moore’, in Music and the Irish Literary Imagination [Oxford Academic] (Oxford UP 2008): | ||

|

[ top ]

|

|

| Moore with family by W. H. Fox (1844) [phot.] and Moore’s harp made by Egan | |

[ top ]

Works

See separate file, infra.

Criticism

See separate file, infra.

Commentary

See separate file, infra.

Quotations

See separate file, infra.

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography writes that Moore was ‘inspired by Prince of Wales’s failure to support emancipation’ to write ‘airily malicious lampoons in verse, collected in The Twopenny Postbag (1813)’; further notes that he destroyed Byron’s memoirs, given him in Venice; wrote graceful life of Byron (1830); ed. Byron’s works; received a literary pension and a civil list pension [both],and wrote The History of Ireland for Lardner’s Cabinet Encyclopaedia; [works]; first collected ed. 1840-41.

[Note, however, that Moore is exonerated of the destruction of Byron’s papers in Humphrey Carpenter, The Seven Lives of John Murray, Publisher (2008) - information received from Michael Drury, Brussels, 2010.]

Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (Washington: Catholic Univ. of America 1904), selects approx. 30 pieces, all melodies. Add bibl. Memoirs, Journals, & Correspondence of TM, ed. Lord John Russell (1st: Longmans 1853-6), 8 vols. Demy 8vo, half-calf and gilt spines; vast amount of material about Byron and others. [185, Eric Stevens Cat. 166].

Stephen Brown, Guide to Books on Ireland (Maunsel 1912), lists M.P. or the Blue Stocking (London 1811); also History of Ireland, 2 vols. (Paris: Baudry 1835).

Sundry Anthologies incl. Arthur Ponsonby, ed., Scottish and Irish Diaries &c (Methuen 1927), incls. extracts from Moore. A. N. Jeffares & Anthony Kamm, eds., An Irish Childhood: An Anthology (London: Collins 1987), et al., incls. passages from Moore.

Peter Kavanagh, The Irish Theatre (Tralee 1946), Thomas Moore 1799-1852; The Gypsy Prince, com. op. (Hay, 24 July 1801); Montbar or The Buccaneers (1804, failed); and M.P. or The Blue Stocking, com op. (Lyceum 9 Sept 1811, 19 nights). Lalla Rookh was produced at Crow St., 4 June 1818, in an operatic version by Michael O’Sullivan (1794-1845), with music by C. Horn, and ran for a hundred nights. Further: Lalla Rookh, an exotic oriental operetta, was written in 1817 at the behest of Longmans, and Moore received £3,000 for the copyright’ [A. C. Patridge, Language and Society in Anglo-Irish Literature, 1984, p.163.]

Arnott & Robinson, English Theatrical Literature 1559-1900: A Bibliography (London: Society for Theatre Research 1970), attribs. Kilkenny Private Theatricals, with a history of private theatres in Ireland, to Thomas Moore [under Moore]. The alternative author is Richard Power. Note that La Tourette Stockwell (Dublin Theatres and Theatre Customs 1637-1820, NY: Benjamin Blom, 1968), cites Moore’s Journal, VIII, 130, 217, 242, as evidence for his authorship. [Moore met his wife at Kilkenny.]

[ See listing of the Works of Thomas Moore in Wikipedia - as attached. ]

[ top ]

Brian McKenna, Irish Literature (Gale Research 1978), Bibl. cites, S. C. Hall, Memory of Thomas Moore (1879) [32pp.]; Stephen Gwynn, Thomas Moore, English Men of Letters series (Macmillan 1905) 203p; James Stephens, ‘Thomas Moore, Champion Minor Poet,’ in Poetry Ireland 17 (1952). Oxford Dict. Quot. has 40 items. There is a life by Terence De Vere White (1977), and a recent edition of the poems with a preface, defending Moore’s use of Bunting, by Seamus Heaney.

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (1980), Vol. 2, Bibl. [in outline only], PERIODICALS, Anthologia Hibernica, 1793-94; Dublin Magazine and Irish Monthly Register, I, Sept 1798, ‘Imitation of Anacreon’s 1st Ode’, p.203. [pagination as in DIL, supra.]. POETICAL WORKS, Irish Melodies, a Selection of Irish Melodies with symphonies and accompaniments by Sir John Stevenson and characteristic words by Thomas Moore, Esq. (London: J. Power.) 1st series, 1st No., 1808; 2nd No. 1808; 3rd, 1810; 4th, 1811; 5th, 1813; 6th, 1815; 2nd Series, 7th No., 1818; 8th No. 1821; 9th No. 1825; 10th No. 1834; Supplement, 1834; National Airs [London/Dublin: Power 1818], 1st No. 1818; 2nd, 1820; 3rd, 1821; 4th, 1822; 5th, 1826, 6th, 1827 [London only]. [Titles not in DIL:] Songs and Glees (Carpenter 1804), seven of Moore’s songs issued on sheets by R. Rhames, Dublin, and J. T. Carpenter, London, &c.; Tom Cribs Memorial to Congress ... by One of the Fancy (Longman 1819), xxxi, 88pp.; Evenings in Greece, First and Second Evenings, the Poetry of Th. Moore, music comp. and selected by H. R. Bishop (London: J. Power n.d.), folio, 210pp. PROSE, Memoirs of Captain Rock, the Celebrated Irish Chieftain, with some Account of his Ancestors Written by Himself [1st edn.] (London: Longman &c. 1824; 4th edn. Longman 1824), xiv, 376pp.; also Do. (Philadelphia: Carey and Lea 1824) [pirate]; Memoirs of the Life of the Right Hon. Brinsley Sheridan [sic] (London: Longman &c. 1825), xii, 719pp.; Letters and Journals of Lord Byron with notices of his life by Thomas Moore 2 vols. (London: J. Murray 1830), viii, 670pp, 823pp.; Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, 2 vols. (London: Longman &c 1831), xi, 307pp; 305pp.; The History of Ireland 4 vols. [in Cabinet Cyclopoedia [see Dion. Lardner] (London: Longman &c 1835-1845), Vol I: 1835, xii, 321; II: 1837, xv, 345pp; III: 1840, xix, 327pp; IV, 1845, xx, 313pp. ALSO A Letter to the Roman Catholics of Dublin (1st ed. London: J. Carpenter 1810), 40pp; ibid., 2nd ed. Dublin: Gilbert & Hodges 1810), [2], 37pp. MISCELLANEOUS, ‘Life of Sallust’, in The Works of Sallust, trans. Arthur Murphy (London: J. Carpenter 1807), 40pp; 2nd ed. (Dublin: Gilbert & Hodges 1810), [2], 37pp; Articles contributed to Edinburgh Review incl. ‘French Novels’, XXXIV, Nov. 1820, p.372; ‘French Romances’, XL, Mar. 1824, p.158; ‘French Literature, ‘Recent Novelists’, LVII, July 1833, p.31; review, ‘[Henry] O’Brien’s Round Towers of Ireland’, LIX, Apr. 1834, p.143; ‘Private Theatricals’, XLIV, June 1826, p.156; ‘Irish Novels’, in Edinburgh Review, XLIII, Feb. 1826, p.356 [list taken from Wellesley Index, omitting Coleridge’s Christabel as proven to be by another author than Moore]. 2ndary Bibl. (Criticism) lists Stephen Gwynn, Thomas Moore, for ‘English Men of Letters’ (1904), 203pp; M. J. MacManus, ‘A Bibliographical Handlist of the first editions of Thomas Moore (rep. from Dublin Mag., 1934.) Terence de Vere White, Tom Moore: The Irish Poet (1977) xiv, 281p; W. F. P. Stockley, Essays in Irish Biography (Cork UP 1933), 191pp., ‘Moore and Ireland’, pp.1-34., ‘The Religion of Thomas Moore’, pp.34-92; S. McCall, Thomas Moore (London: Duckworth; Dublin: Talbot 1935), 132pp.; Hoover H. Jordan, ‘Thomas Moore’, in C. W. & L. H. Houtchens, eds., English Romantic Poets and Essayists (NY: MLA 1957, 1966), pp.199-220; G. Vallat, Thomas Moore, sa Vie et ses Oeuvres (Paris: A. Rousseau; London: Asher; Dublin: Hodges Figgis 1886), xx, 293pp.; A. B. Thomas, Moore en France (Paris: Champion 1911), xx, 173pp.).

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1, 1250-1254, selects Intolerance: A Satire [1056-57]; also selections [1057-1069] from Irish Melodies:“Go where glory waits thee”;“Remember the glories of Brian the brave”;“Erin! remember the smile in thine eyes”;“Oh! breathe not his name”; “she is far from the land”; “When he, who adores thee”; “Rich and rare were the gems she wore”; “The meeting of the waters”; “How dear to me the hour”; “Let Erin Remeber the days of old”; “The Song of Fionnula”; “Believe me, if all those endearing young charms”; “Erin, Oh Erin”; “Oh! blame not the bard”; “Avenging and bright”; “At the mid hour of night”; “One bumper at parting”; “ ‘tis the last rose of summer”; “The Minstrel Boy”; “; Dear harp of my Country”; “In the morning of life”; “As slow our ship”; “when cold in the earth”; “Remember thee”; “Whene’er I see those smiling eyes”; “Sweet Innisfallen”; “As vanquish’d Erin”; “They know not my heart”; “I wish I was by that dim Lake”. From National Airs:“Oft on the stilly night”; and Songs, Ballads, and Sacred Songs:“The dream of home”; “The homeward march”; “Calm be thy sleep”; “The exile”; “Love thee, dearest? love thee?”; “My heart and lute”; “ ‘tis all for thee”; “Oh, call it by some better name”. BIOG at 1069 calls him son of grocer and an adoring mother; beneficiary of recent changes in TCD entrance; remembered being taken on the knee of Napper Tandy and hearing patriotic toasts in 1792; befriended in London by Lord Moira, Duke of Bedford, and Marquis of Lansdowne, Russell, Scott, and Byron; unpaid debts of £6,000; forced to live abroad 1819-22; satire more politically open in hostility to Tory politicians on the ill-treatment of Ireland than his other work; Intercepted Letter went to 14 eds. in one year; m. Bessie Dyke from Kilkenny; deaths of five children; lawsuit led to his acquiescence in the burning of Byron’s memoirs; triumphant return to Dublin in 1835; ill in 1847; distressing senility; d. Sloperton; outlived by his mother by 13 yrs; she presented his library to the RIA. Further Remarks at xxiii, 934-35; 954n; 962; 1076; 1078-79; 1081; 1082; 1129n, 1134; 1138n; 1201; 1250-54; 1269n; 1278n; 1285n. BIBL (as supra).

Petri Liukkonen, Author’s Calendar [Open Commons] lists - The Minstrel Boy by A.G. Strong (1937); The Life of Thomas Moore, Ireland’s National Poet by Herbert O. Mackey (1951); The Harp That Once--; A Chronicle of the Life of Thomas Moore by Howard Mumford Jones (1970); Tom Moore: The Irish Poet, by T. de Vere White (1977); The Last Rose of Summer: The Love Story of Tom Moore and Bessy Dyke, by Margery Brady (1993); The Life and Poems of Thomas Moore, by Brendan Clifford (1993); The Literary Relationship of Lord Byron and Thomas Moore, by Jeffery W. Vail (2000); The Literary Relationship of Lord Byron and Thomas Moore, Jeffrey W. Vail (2001); Ireland’s Minstrel: A Life of Tom Moore: Poet, Patriot and Byron’s Friend, by Linda Kelly (2006); ‘Thomas Moore’s Orientalism’, by Allan Gregory, in Byron and Orientalism, ed. Peter Cochran (2006); A Political Reading of Thomas Moore’s Lalla Rookh by Claudia Ballhause (2007); Bard of Erin: The Life of Thomas Moore, by Ronan Kelly (2008); The Reputations of Thomas Moore: Poetry, Music, and Politics, ed. Sarah McCleave & Triona O’Hanlon (2020. )

[ top ]

Belfast Central Public Library holds Alciphron (1839); Cantus Hibernici (1856); Epicurean (1897); Historical Ballads Poetry of Ireland (1912); History of Ireland, 4 vols. (n.d.); Irish Melodies (1856, 1873); The Life and Death of Lord Edw. Fitzgerald (1975); Loves of the Angels (1823); Lalla Rookh (1822); Lyrics and Satires (1919); Memoirs, Journal, and Correspondences (1853-6); Memoirs of Captain Rock (1824); Memoirs of Lord Edward Fitzgerald (1897); Memoirs of Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1825); Notes from autograph letters to Mr. Power [i.e. Notes from letters to music publisher, 1854]; Paradise and the Peri (n.d.); Poetical Works (1854, 1873, 1899); Prose and Verse (1878); Selection of ... Melodies (1899); Works (1826).

University of Ulster Library (Morris Collection) holds Poetical Works (18?81); Life and Death of Lord Edward Fitzgerald, 2 vols. (Longmans 1832); also Stephen Gwynn, Thomas Moore (1905); S. C. Hall, Memory of Thomas Moore (n.d.); L. A. G. Strong, Minstrel Boy (1937).

Mooreana: a collection of 530 items of Mooreana were offered by C. C. Kohler, 12 Horsham Rd., Dorking, Surrey, RGH4 3JL, England, in [?]1996, with a catalogue introduced by Michèle Kohler.

[ top ]

Notes

Lalla Rookh: An Oriental Romance (1817) - considered a major landmark in Romantic orientalism for which Moore was paid £3,000. It consists of four poems, with a connecting tale in prose, ‘The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan,’ ‘Paradise and the Peri,’ ‘The Fire-Worshippers,’ and ‘The Light of the Haram.’ The central character is princess Lalla Rookh, the linking narrative tells of a journey from Delhi to Cashmere. On her way to be married to the King of Bucharia a young poet, Feramorz, tells stories. In ‘The Veiled Prophet of Khorassan’ the beautiful and mourning Zelica is killed by his lover Azim, whom Zelica believed to have died in a battle. ‘The Paradise and the Peri’ concerns itself with a spirit, a peri in Persian mythology, who tries to gain admission through the heaven’s gates. ‘The Fire-Worshippers’, also based on Persian mythology, tells the tragic love story of young Hafed and Hinda. In ‘The Light of the Harem’ Nourmahal wins back the love of her husband Selim. Lalla Rookh’s journey ends happily: she falls in love with the poet who turns out to be the King of Bucharia, her prospective husband. ‘Paradise itself were dim / And joyless, if not shared with him!’ (See Author’s Calendar - online; accessed 31.04.2023.

Further remarks: ‘Moore was even a closer friend to Byron than Shelley. Their poetry often shared common themes, attitudes, and styles - critics even considered Moore’s magnum opus Lalla Rookh an imitation of Byron. The British Revue [sic] condemned in 1817 Byron and Moore as the two principal practitioners of the ‘new Oriantal school’ of writing that was ruining the morality of the English youth. (The Literary Relationship of Lord Byron and Thomas Moore by Jeffrey W Vail, 2001, pp. 7-8.)’ [Petri Liukkonen, op. cit. - online.]

Note: Author’s Calendar is created and written by Petri Liukkonen and available in Open Commons. The whole article is a biography and bibliography of Moore with bibl. listings up to 2020 as copied in References - supra.]

[ top ]

Irish Melodies (No. 1 & 2, 1808): Eight of the twelve melodies, including Drennan’s ‘rebellious but beautiful song, “Erin”’ in Moore’s first anthology were from Bunting’s, along with two others from Charlotte Brooke and J. C. Walker.

[Note: For Bunting’s response to Moore’s use of the airs to frame modern romantic poetry, see under Bunting - as supra.]

French response: Augustin Thierry called him ‘the foremost Irish poet and one of the greatest poets of our age’ (Censeur Européen, 24 Nov. 1819); ‘Believe me if all those endearing Young Charms’ trans. by Gerard de Nerval. (Cited in Patrick Rafroidi, ‘Thomas Moore: Towards a Reassessment?’, in Michael Kenneally, ed, Irish Literature and Culture, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1992, p.56.)

John O’Keeffe: Moore acknowledged his indebtedness to O’Keeffe’s Irish songs in the first vol. of his Poetical Works: ‘With acting is associated the very first attempts at verse-making to which my memory enables me to plead guilty. It was at a period, I think, even earlier than the date last mentioned, that while passing the summer holidays with a number of other young people, at one of those bathing places, in the neighbourhood of Dublin, which afford such fresh and healthful retreats to its inhabitants, it was proposed among us that we should combine together in some theatrical performance; and The Poor Soldier and Harlequin Pantomime being the entertainments agreeed upon, the parts of Patrick and the Motley hero fell to my share. I was also encouraged to write and recite an appropriate epilogue for the occasion ...’ (Poetical Works, p.16; quoted in Robert Ward, Encyc. of Irish Schools, 1500-1800, 1995, p.154.)

William Hazlitt (The Spirit of the Age, or, Contemporary Portrait, London, 1825): ‘If these national airs do indeed express the soul of impassioned feeling in his countrymen, the case of Ireland is hopeless. If these prettinesses pass for patriotism, if a country can heave from its heart’s core only these vapid, varnished sentiments, lip-deep, and let its tears of blood evaporate in an empty conceit, let it be governed as it has been. There are here no tones to waken Liberty, to console Humanity. Mr. Moore converst the wild hard of Erin into a musical snuff-box!’ (Vol. II, p.84; quoted in Catherine A. Jones, ‘Our Partial Attachments’: Tom Moore and 1798’, in Eighteenth-Century Ireland / Iris an dá chultúr, Vol. 13, (1998), pp. 24-43.

Thomas Addis Emmet was scathing of Moore’s lack of commitment to the United Irishmen’s ideals and to their political agitation. (See Terence de Vere White, Tom Moore, London: Hamish Hamilton 1977, p.28; cited in S. Slack, MADip CA essay, UUC 2002-03.)

Daniel O’Connell (1): Thomas Moore’s Captain Rock was likened by Daniel O’Connell to the Uncle Tom’s Cabin of the Catholic Emancipation Movement (see O. McDonagh, The Emancipist: Daniel O’Connell 1775-1829, p.17; quoted in M. Howe, ‘Tears and Blood: Lady Wilde and the Emergence of Irish Cultural Nationalism’, Tadhg Foley & Seán Ryder, eds., Ideology in Ireland in the Nineteenth Century, 1998, p.161; cited in Claire Connolly, ‘Writing the Union’, in Dáire Keogh & Kevin Whelan, eds., Acts of Union: The Causes, Contexts and Consequences of the Act of Union, Dublin: Four Courts Press 2001, p.186.)

Daniel O’Connell (2): At the preliminary meeting of the public dinner organised for Moore in May 1818, O’Connell professed that ‘there could not live a single Irishman so lost to feeling of affection for his country, as not to feel pride and pleasure at hearing the name of Moore’; further: ‘It [is] a name that raised the fame of Irish talent, and place[s] the poetic character of his country on the highest pinnacle of literary glory.’ (Liam de Paor, ‘Tom Moore and Modern Ireland’, Landscapes with Figures (Dublin: Four Courts 1998, p.79.)

The Prince Regent: The Prince’s low opinion of the Memoirs and Life of Sheridan is reported in Lord Dufferin’s Preface to [his mother] Lady Dufferin’s Songs, Poems, and Verses (London: John Murray 1894) [see under R. B. Sheridan, q.v.].

[ top ]

Sir Walter Scott: the poetic phrase ‘a tear and a smile’ which came to be considered a hallmark of the Irish (or, more broadly Celtic) temperament is usually attributed to Moore - ‘Moore too much loves to weep’ - but can equally be met with in Sir Walter Scott. Which was the original? Vide “Lochinvar”—

| ‘The bride kiss’d the goblet: the knight took it up. He quaff’d off the wine, and he threw down the cup. She look’d down to blush. and she look’d up to sigh. With a smile on her lips and a tear in her eye. He took her soft hand, ere her mother could bar, - “Now tread we a measure!” said young Lochinvar.’ |

| [ Stanza 5 ] |

Compare the instances of the phrase in Moore’s lyrics [search Quotations, supra; and see also gloom and levity in his letter to Sir John Stephenson]. Note also that D. J. O’Donoghue’s defines humour as ‘a fusion of smiles and tears’ quoting ‘a French writer’ in his introductory essay to The Humour of Ireland (London & Newcastle-on-Tyne: Walter Scott Publ. Co. [1894]) [as attached] - whcih suggests a earlier, common source for all subsequent incidents of the phrase. (But who was the French author?)

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Shelley’s “Adonais” includes a reference to Thomas Moore: ‘... from her wilds Ierne sent, / The sweetest lyrist of her saddest wrong ...’.

Lord [George] Byron (1): Byron offered The Corsair to Moore with a dedicatory letter: ‘... While Ireland ranks you among the firmest of her patriots [... &c.]’. Further, in a verse letter to Moore Byron wrote: ‘when a man hath no freedom to fight for at home, / Let him combat for that of his neighbours;/Let him think of the glories of Greece and of Rome / And get knocked on the head for his labours.’ See W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (1984).

Lord [George] Byron (2): speaking of the origins of the Irish Language, Byron wrote: ‘The antiquarians who can settle time, / Which settles all things, Roman Greek, or Runic, / Swear that Pat’s language sprung from the same clime / With Hannibal, and wears the Tyrian tunic / Of Dido’s alphabet. (Don Juan, 8.23.3-7; with ftns. on Vallancey and Lawrence Parsons, prob. from information of Thomas Moore; cited in Elizabeth Butler Cullingford, ‘British Romans and Irish Carthaginians: Anticolonial Metaphor in Heaney, Friel and McGuinness’, PMLA, March 1996, pp.222-36, p.226.)

Lord [George] Byron (3): Union speech - ‘Adieu to that Union so called, as “lucus a non lucendo”, a Union from never uniting; which in its first operation, gave a death-blow to the independence of Ireland, and in its last may be the cause of her eternal separation from this country. If it must be called a Union, it is the union of the shark with its prey; the spoiler swallows up his victim, and thus becomes one and indivisible. Thus has Great Britain, swallowed up the parliament, the constitution, the independence of Ireland’ (Speech in House of Lords, 1 April. 1812; cited as epigraph, inter alia., in J. C. O’Callaghan, The Green Book [ ... &c.], 1841.)

Lord [George] Byron (4): In August 1813 Moore wrote to Mary Godfrey: ‘Never was anything more unlucky for me than Byron’s invasion of this region, which when I entered it was as yet untrodden [...] instead of being a leader as I looked to be, I must dwindle into a humble follower - a Byronian. This is disheartening.’ (Letters of Thomas Moore, ed. Wilfred S. Dowden, OUP 1964, Vol. 1, p.275.) Within the month, however, Byron was writing to Moore: ‘Stick to the East ... The little I have done in that way is merely “a voice in the wilderness” for you; and if it has had any success, that also will prove that the public are orientalizing, and pave the path for you.’ (Byron, Letters and Journals, ed. Marchand, 1973-82, Vol. 3, p.101.) [Both the foregoing quoted in Jerry Nolan, J. C.M. Nolan, ‘In Search of an Ireland in the Orient: Tom Moore’s Lalla Rookh’ [pub. priv. [.pdf - online].

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats: discussing the manner in which Yeats tried to remove Moore from the Irish canon, John Frayne notes that his works are omitted from the list of best books that he produced in 1895 ,and that of the two included in his Book of Irish Verse (1895) one contains a howler, viz., ‘The cheerful homes now broken!’ for ‘The cheerful hearts now broken!’ (See John Frayne, Uncollected Prose, Vol. I, 1970, p.38).

Augustus Stopford Brooke: Brooke makes comments on Moore in his prefatory notice to the selection of his poems in A Treasury of Irish Poetry in the English Tongue (1900), as quoted by Thomas Kinsella [see under A. S. Brooke, q.v.].

William Carleton: Carleton anathemised the statue of Moore in College St., Dublin, as ‘one of the vilest jobs that every disgraced the country, such a stupid abomination as has made the whole kingdom blush with indignation and shame.’ (See obituary notice on John Hogan, sculpt. - whose statue was rejected - in Irish Quarterly Review [1858]; quoted in Ben Kiely, Poor Scholar, 1947; 1972, p.150.)

Cf. James Joyce: Joyce calls the figure of Moore facing the Bank of Ireland in Westmoreland St. ‘a Firbolg in the borrowed cloak of a Milesian’ with ‘servile head [and] shuffling feet’ and ‘humbly conscious of its indignity’ (Portrait, [Rev. Edn.] 1967, p.183). but later embodied all the titles and airs of all of Moore’s Melodies in the punning fabric of Finnegans Wake (see James Atherton, Books at the Wake).

Note: In Ulysses, Joyce incorporates glancing slights at the writer already aspersed in A Portrait - e.g. the Bloomism: ‘The harp that once did starve us all.’(U8.606.) See also the allusion to Robert Emmet’s bien aimée Sarah Curran: in the “Cyclops” episode: ‘the Tommy Moore touch about Sara Curran and she’s far from the land.’ (U12.500.) Yet in Finnegans Wake (1939), he purportedly included all the song-titles and all the airs of Moore’s Melodies (or ‘maladies’).

Eugene Sheehy, speaking of Joyce’s attitude to the statue, writes: ‘Joyce had legends for some of the Dublin statues [...] And the statue of the poet Moore in College Green [recte College St.] supplied with right forefinger raised the satisfied answer, “Oh! I know.”’ (Ulick O’Connor, The Joyce We Knew, Cork: Mercier Press, 1967, p.27.)

Thomas Carlyle: Carlyle’s French Revolution, I.iv., contains an account of the Sept. massacres of 1792 by one Dr. Moore, supposed to be the poet and an eye-witness to same: ‘Witty Dr. Moore grew sick on approaching, and turned into another street.’ (Chapman & Hall Edn. [London; n.d.]), Vol. 1, p.25 (ftn., Moore’s Journals, I, pp.185-95.)

Lord Macaulay: Macaulay reviewed ‘Moore’s Life of Lord Byron’ in the Edinburgh Review, June 1831: ‘Considered merely as a composition, it deserves to be classed among the best specimens of English prose which our stage has produced ... evidentally written ... for the purpose of vindicating ... the memory of a celebrated man’ (Critical and Historical Essays, new edn., Longman’s 1870, p.141). Further: ‘Of the deep and painful interest which this book excites no abstract can give a just notion’ (idem., p.142).

Thomas Davis: Davis refers to Moore in his lecture on ‘The Young Irishman of the Middle Classes’, given before the TCD Historical Society, 1839, and reprinted in three installments in The Nation (1848).

Duffy & Co.: Duffy issued a Centenary Edition of Irish Melodies (Dublin: O’Connell St. Duffy 1892) as ‘complete’; incls. symphonies and accompaniments by Sir John Stevenson and another (copy held in home of Louis Cullen).

[ top ]

Hector Berlioz: According to his own account, Berlioz was ‘struck by the pride, tenderness and deep despair of Moore’s poem to Robert Emmet, so much so that ‘music flowed out of me’ - resulting in his rendering of nine songs from the Irish Melodies as Irlande [9 songs], being Opus Two of his works, which he himself admired for its ‘surge of somble harmony’. His interest in Moore was inspired by his tumultuous love-affair with Harriet Smithson. The elegy to Robert Emmet was sung by Thomas Hamson, with Geoffrey Parsons accompanying, on BBC 3, 14 April 2010 as part of the Berlioz “Composer of the Week” season. Berlioz also set poems by Pierre-Jules-Theophile Gautier, Lamartine and Gérard de Nerval (after Goethe). For French versions of the pieces in verse and prose by Moore that Berlioz used in Irlande, see Robert Ellis Crawford Music Foundation (St. Louis), Leider > Berlioz online; accessed 14.04.2010. For translations of Moore’s by sundry hands which supplied the text for Berlioz’s Opus 2 (“Irlande”), see attached.

Seamus Heaney: Heaney, who has written a striking introduction to a short selection from the point of view of Catholic nationalist apologist (c.1984) [copy in Rare Books, TCD], keeps an oil portrait of Thomas Moore, by school of Sir James Sleator, on his living room mantelpiece on Strand Rd., Dublin.

Seamus Deane: Deane writes, ‘Captain Rock contains a Catalogue Raisonné of Hedge School literature.’ (The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, 1991; under Moore.) Note that Seamus Deane gave a public lecture on Moore at the RIA in March 2002.

Paul Durcan: Durcan has a poem on Thomas Moore in Crazy About Women (1991).

Led Zeppelin: The line, ‘Speak to me only with your eyes’ is used in Led Zeppelin’s “Rain Song”.

Portraits: among numerous portraits of Moore is one by Daniel Maclise (rep. in Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, Vol. 1, Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980). An oil portrait of Thomas Moore by an unknown hand is held in National Portrait Gallery (London); A portrait of the young Tom Moore attrib. to Thomas Phillips was sold at Sotheby’s (London) in the range of £4-6,000 (6 April 1993). An oil portrait occupies a prominent place in the Dublin home of Seamus Heaney at Strand Rd., Dublin.

12 Aungier St.: the house in which Moore was born was once occupied by Oliver Goldsmith’s sister. It was originally built with a “Dutch Billy” gable which was removed in 1866.. (See Ronan Kelly, ‘Still Home to Irish Melodies’, in The Irish Times (12 Jan. 2002), Weekend; “Literary Landmarks” [column].

“The Last Rose of Summer”: the lyric was written by Moore wrote at Jenkinstown Park, Co. Kilkenny, in 1805, and set to music by Sir John Stevenson, being published in Irish Melodies (1807). The poem became the subject of “Theme and Three Variations for flute and piano” [Op. 105] by Beethoven, a late work, as well as a Fantasia in E major by Mendelssohn [Op. 15]. Friedrich von Flotow set the song in his opera Martha (1847), and it is this version which is reflected in Joyce’s Ulysses. A holograph manuscript by Beethoven including the song, which he set to music for the Scottish publisher George Thomson, was offered for sale at Christie’s with a reserve of £560,000. (See John Armstrong, Irish Times report - cutting [q.d.]). Wikipedia notes that the best-known melody is said in Ireland to have been composed by George Alexander Osborne of Limerick, not Sir John Stevenson.

[ top ]