Life

| 1795-1829; [Jeremiah Joseph; fam. “Gerry”]; b. Cork; intended for Maynooth and priesthood, he studied at TCD for 2 years, and joined British Army and and was a British Unionist in politics; entered TCD as a medical student, and won poetry prizes; taught in William Maginn’s school, Cork; contrib. to Bolster’s Quarterly and The Mercantile Chronicle; collected ballads and legends in Munster (now lost); |

| his classic ballad “Gougane Barra” appeared in 1826; suffered from TB of the throat and travelled to Lisbon in search of health, 1827; d. in Lisbon, 29 Sept.; Collected Poems issued in 1861; ‘The Literary Remains of Jeremiah J. Callanan’ are held in the Royal Irish Academy as RIA MS 12.1.13; John Windele wrote a memoir (Bolster’s Quarterly Magazine, Vol. III, p.292). ODNB PI JMC DIB DIW DIH DIL MKA RAF OCIL FDA |

Works

The Recluse of Incidony and Other Poems (1830); Michael Francis McCarthy, ed., The Poems of J. J. Callanan (1847); Do., shorter edn. (1861); also in Gems of the Cork Poets: comprising the complete works of Callanan, Condon, Casey, Fitzgerald, and Cody (Cork: Joseph Barter & Sons, Academy Street [1883]), xvi, 510, [2]pp. [18.6cm.]. Also, Charles Wood, “And Must We Part?”: An Irish Melody ([q. pub.] 1931).

Reprint, Gregory A. Schirmer, ed., The Irish Poems of J. J. Callanan (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 2005), v, 153pp.

Criticism

B. S. Lee, ‘Callanan’s “The Outlaw of Loch Lene”’, Ariel, vol. 1, No. 3 (July 1970), pp.89-100; Robert Welch, ‘Some Cork Translators’, in A History of Verse Translation from the Irish, 1789-1897 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1988); Welch,

Irish Poetry from Moore to Yeats (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), q.pp.

[ top ]

| Michael Doheny, The Felon’s Track (1849): |

|

| Doheny, op. cit., 1849 edn., p.127 [available at Internet Archive - online]. |

[ top ]

W. B. Yeats: ‘An honest style did not come into English-speaking Ireland until Callanan wrote three or four naive translations from the Gaelic. Shule Aroon and Kathleen O’More had indeed been written for a good while, but had no more influence than Moore’s best verses. No, however, the lead of Callanan was followed by a number of translators, and they in turn by the poets of Young Ireland, who mingled a little learned from the Gaelic ballad writers with a great deal from Scott, Macaulay, and Campbell, and turned poetry once again into a principal means for spreading ideas of nationality and patriotism. [... &c.] (‘Modern Irish Poetry’, in Irish Literature, gen. ed. Justin McCarthy, NY/CUA 1904, Vol. III, p.vii.)

Robert Farren, Course of Irish Verse (London: 1948): ‘He was inside Irish life, and it did not seem to him a Donnybrook Fair. He did not decide to find gravity within that life; he probably did not decide anything about it, one way or another; he just was of that life and could not treat it as an outside entertainment got up specially for him. He can scarcely have realised how new that position was, among our English-writing poets.... Not alone is this a grave, strong speech [trans. Ó Gnive’s Lament], different from the whiskey giggle of Handy Andy, but it swells the diaphragm lacking in the poems of the [sic] Nation ... to find it like Lionel Johnson is to measure it well, and by no means to dispraise it.’ (pp.22-23).

Sean O’Faolain, The Irish: A Character Study (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1947), writes at some length about Callanan: ‘Yet, in one way, the Young Irelanders were wise in their generation: they insisted on the use of native material. To show the absolute rightness of this let us look, very shortly, at the good (and Bad) example of one of their predecessors [...] who died in 1829. / This poet is remembered to-day for ballads and songs that propose him as the first really popular Irish poet writing in English: see his fine poem on “Gougane Barra”, his ballad “The Revenge of Donal Cawm”, his translation of some of the really good Gaelic songs of the eighteenth century, such as “O say my brown Drimin, thou silk of the kine”, or “The Convict of Clonmel”. The truth is that in so far as he is a popular poet he is popular in spite of himself, almost by accident, and his history is a revelation of how easily a poet may miss his true inspiration. At Trinity College he won his first recognition for a poem on, of all things, “Alexander’s Restoration of the Spoils of Athens”. He wrote a sycophantic poem in praise of George IV. For years his models were English models. / Byron was the “bard of my boyhood’s love”, his “eagle of song”, his “fountain of beauty”.’ [Cont.]

Sean O’Faolain (The Irish: A Character Study, 1947) - cont.: ‘In theory there was nothing wrong with all this. In practice the effect on a young provincial Irishman was not good: as one may see at one glance. / The night was still, the air was balm, Soft dews around were weeping ... / All that came of it, that is, were pleasant, pseudo-Byronic verses of which one may say that none of them go very far except in the sense that they all go much too far - from home, from life, from reality: Thy name to this bosom / Now sounds like a knell; / My fond one, my dear one, - For ever farewell. / A Byron could write light songs in that theme and make them ring with passionate tenderness; not an unsophisticated Irish country lad pretending to be a Byron. Thus, Callanan’s most ambitious poem, and the poem in which he took most pride, was ‘The Recluse of Inchidony.’ The difference between something that is just a pose, and something that is experienced may be seen in the comparison of eight lines of ‘Inchidony’ with eight lines of ‘Childe Harold.’ Here is Callanan: ‘Tis a delightful calm. There is no sound / Save the low murmur of the distant rill. / A voice from heaven is breathing all around / Bidding the earth and restless man be still. / Soft sleeps the moon on Inchidony’s hill And on the shore the shining ripples break / Gently and whisperingly at Nature’s will, / Like some fair child that on its mother’s cheek / Sinks fondly to repose in kisses pure and meek. [...’; 123.) [Cont.]

Sean O’Faolain (The Irish: A Character Study, 1947) - cont.: Quotes lines from Childe Harold, commencing, ‘It is the hush of the night and all between / They margin and the mountains dusk yet clear ...’] / ‘The light drip of the suspended oar’ is alone enough to mark the distinction. Callanan has not learned to revere the simple detail of life about him, that stuff of which later Irish writers were to make their best work. He therein reflects the lack of pride of his century. He is, in fact, the counterpart in English of the irrealism of a great deal of eighteen-century Gaelic verse, equally eager to escape reality. / The romantic movemt - of which, to make another essential point, all Irish rebellion (Tone and the Young Irelanders and the rest) is a reflection, and all Irish literature the offspring - let Callanan out of his dilemma. Scott had resurrected the clansman. [Goes on to cite Bishop Percy, Ritson, Edward Bunting, Charlotte Brooke, Joseph Walker.] What to these was antiquity to Callanan was everyday life. Callann looked [134] about him and began finely to translate songs he had often listened to, but, until now, never heard. He writes patronisingly of them, not recognising the gifts even as he took them, calling them “popular songs of the lower orders”, and saying, “I present them to the public more as literary curiosities than on any other account.” / The point is made. The Irish writer was a provincial while he imitated slavishly and tried to write beyond his talents; he ceased to be a provincial when he wrote of what he knew and could describe better than anybody else. [&c.]’ (O’Faolain, p.133-35.)

Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English: The Romantic Period, 1789-1850 (Gerrards Cross: Colin Smythe 1980), Vol. 1, points out that the ODNB gives his name as Jeremiah John and cites the ‘Memoir’ printed with poems in the 1861 edition [i.e., Gems], and another in Bolster’s Quarterly Magazine (1831, pp.28-97); Rafroidi characterises “The Recluse” as pseudo-Byronic (op. cit., p.42).

[ top ]

Robert Welch, ‘Language and Tradition in The Nineteenth Century’, in Changing States: Transformations in Modern Irish Writing (London: Routledge 1993): ‘[Thomas Moore went to London and brooded upon “vanquished Erin ” and her woes. J. J. Callanan, the Cork poet, went to West Cork to try to realize his life-image. He was one of the first of those in Ireland , who, disappointed with city life, “fly to the mountains”. (John Windele, ‘Memoir of the Late Mr. Callanan’, in Bolster’s Quarterly Magazine, Vol. III, p.292.) This last is a phrase he used in a letter to John Windele, the Cork antiquary. He planned a series of Munster Melodies along the Moore line, which he tried to research himself in Bandon, Clonakilty, Bantry and Gougane Barra. Nothing much remains: a few stray letters in a collection gathered by his friend Windele; a handful of translations; and a longish poem in imitation of Byron. There may be more as yet undiscovered, but it is unlikely. There is one superb poem, a poem which summarizes much of {22} what has been said so far about a sense of absence and the lack of a system to represent how people are in their lives. That is “The Outlaw of Loch Lene”. Purporting to be a translation (it is in fact an amalgam, drawn from various sources), it re-creates in English a certain kind of Irish love song - the kind where the man bewails the loss of his woman, and in which the world of nature seems to sympathize with his plight. But more interesting than that is the consideration that the speaker of the poem is outside the law, he has no system, no set of signs. And the language that Callanan uses, while inspired by the imagery and runs of the love songs, itself goes astray into a serial progression of images, that move outside the ordinary and the normal to create a sense of continuous shift and difference. It is a writing continuously evading the requirement that writing such as this, which has a strong narrative overtone, leads the reader to expect that a clear story be told. It continuously breaks the sense-expectation and yet retains an impassioned and forceful rhetorical drive: [Quotes “The Outlaw of Loch Lene”, as in Quotations, infra. ]

Robert Welch (‘Language and Tradition in The Nineteenth Century’, 1993) - cont.: ‘In this poem we do not know what the terror is, nor how it is that {23} the girl lives by the lakeside. It may be that she is dead, and that this is why the outlaw is living in the glen. But the reader will see that these kinds of consideration have nothing to do with the effect of the poetry: this derives from a sense of strangeness that the writing conveys, a hidden secret mystery, towards which the poetry gestures, but which it does not explicate. Such a quality is frequently found in Gaelic love song: Tá crann arm san ngairdin / Ar a bhfásann duilleabhar a’s bláth buí, / An uair leagaim mo lámh air / Is láidir nach mbriscann mo chroí. [There’s a tree in the garden

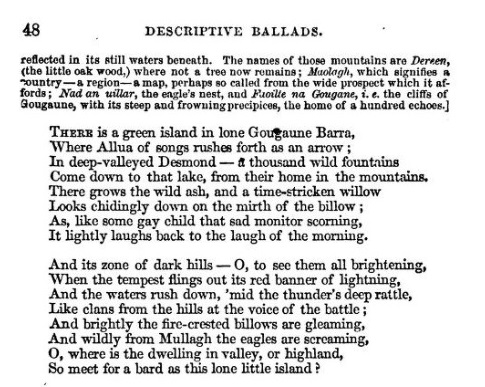

On which grows foliage and yellow flowers, / When I put my hand on it / My heart nearly breaks] (Douglas Hyde, The Love Songs of Connaught , Dublin 1893, p.94.) / But in “The Outlaw” Callanan takes this quality of sudden sharp realization and converts it into the organizing principle of the entire poem, so the piece drives forward with an excitement all the more effective for the strange, mysterious images in which it is presented. It is highly successful but it is very odd. It is intriguing because of the way it slides off its theme or narrative, to concentrate on the rhetorical drive. A central meaning remains unsaid, which does not matter in such a powerfully compacted poem as this, but when Callanan attempts to write analytical and historically responsible verse, as in “The Recluse of Inchydoney”, he fails to find a form for his emotion.’Robert Welch (‘Language and Tradition in The Nineteenth Century’, 1993) - cont.: ‘Callanan turned away from Moore’s example and the imperial model of Burke. He sought out a community in West Cork , but he became a provincial. An unruly temperament, he searched for an alternative tradition to the dominant one with which he was confronted in the prosperous, mercantile Cork of the early nineteenth century. Again, given the circumstances, given his attitude, it was inevitable. There was a community in West Cork to which the poet wished to relate, but it was without the power of expressing itself to itself, publicly. There were West Cork poets writing in Gaelic, for their own people, but that community had become a closed system within the larger closed-off system of Ireland itself. / Callanan longed for continuity and he looked for a source, {24} identifying it, in another poem of his, “Gougane Barra”, with the lake of that name, a black circle of water at the bottom of a cauldron of mountains in West Cork. Here, he says, the legends “darkly” slept. It was his ambition to awaken them, but he failed. No renovation takes place because, for this to happen, there would need to be not just an audience for Callanan’s work but a community, from which, through which, and to which he could speak. He lacked, in other words, a language, a system of adequate representation. His talent, lyrical and impulsive, needed a strong network of codes within which, against which, to work.’ (pp.23-24.)

[ top ]

Fergal Gaynor, ‘“An Irish Potato Seasoned with Attic Salt”: The Reliques of Fr. Prout and Identity before The Nation’, in Irish Studies Review, 7, 3 (Dec. 1999), pp.313-24, notes that ‘Callanan’s case ... is somewhat tragic. Committed to a unification of the sese of an ancient and autonomous Irishness with his fundamentally Romanticist outlook, but in an era before the Young Ireland Movement had provided a focus and a social profile for such aspirations, Callanan ultimately fell between two stools. He was a talented translator form the Irish (unlike Mangan he understood the poems in the original) and had, under Maginn’s patronage, published in Blackwood’s, but he ultimately seems to have become lost in a spiritual limbo between native Irish culture, Romantic Celticism, and an embryonic Irish nationalism. In his wanderings in West Cork and in poems like “Gouganbarra” and The Recluse of Inchidony, Callanan constructed a bardic persona in a hybrid medium of Hiberno-English and the Romanticism [317] of Byron and Scott, which never achieved autonomy. In Callanan we see the emergence of a need for a nationalist ideology in order to give idetnity to the educated Irish who could look neither to England nor to a cosmopolitan Europeanism for sources of cultural locatedness.’ (317-18).

Claire Connolly, ‘Irish Romanticism, 1800-1839’, in Cambridge History of Irish Literature (Cambridge UP 2006), Vol. I [Chap. 10], “Poetry” [sect.]: ‘Maginn promoted the work of a fellow Cork poet, Jeremiah Joseph Callanan (1795-1829). He published Callanan’s translations in the pages of Blackwood’s, perhaps in the hope of attaching his talents to the magazine’s brand of Counter Enlightenment cultural nationalism. A Catholic, Callanan had attended Maynooth Seminary in County Kildare but left after two years. He went from there to Trinity College, Dublin and then on to a short period of military service. In Cork, Callanan worked as an assistant in Maginn’s father’s school, only finally to die in Portugal, having travelled there as a tutor to a merchant family. / Callanan spent a period travelling around Cork and Kerry, collecting stories and songs. Remembered now chiefly for his translations of the poems he encountered, it is worth noting Callanan’s quasi-anthropological relationship to his material and the extent to which, as Robert Welch reminds us, he turned his eyes to London even as he roamed the roads of west Cork. Callanan’s significant formal achievements are discussed by Matthew Campbell [Cambridge Hist. of Irish Literature, Vol. 1, Chapter 12], but it is worth noting here how the poetry speaks from a place located somewhere between English and Gaelic cultures: the overall result is an aesthetic that moves between intimacy and distance, and calls to mind the “migratory impulse” of the national tale./ Callanan may also have written a lost manuscript novel, based on a legendary tale concerning Lough Ine (near Skibereen); he also published in the Cork-based Bolster’s Magazine under the editorship of the antiquarian John Windele. His original poetry inhabits a characteristic rhythm: a soaring moment of hope builds up only to fall away (“But oh!”) in an atmosphere of delicious agony. [...]’ (p.438; for longer extracts from this chapter - including notes omitted here - see RICORSO Library, “Irish Critical Classics”, via index, or direct.)

[ top ]

|

||||||

[ top ]

|

||||||||||||||||||||

[ top ]

References

C. G. Duffy, ed., Ballad Poetry of Ireland (1848), contained “The Outlaw of Loch Lene”; also printed in Arthur Quiller Couch, ed., Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1918 (new ed. 1929), p.646; also in Brendan Kennelly, ed., Penguin Book of Irish Verse (1970).

Dictionary of National Biography calls him Jeremiah John Callanan and styles him ‘an Erse scholar’ whose poems were printed in 1830.

D. J. O’Donoghue, The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical Dictionary (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co 1912), lists Recluse of Inchidony, and Other Poems (1830), with MS letters to Maginn and Crofton Croker in copy at BL; Poems of J. J. Callanan (Cork 1847; Dublin 1861); also poems in Gems from the Cork Poets (1883); entered as medical student in Dublin; returned to Cork and stayed with different people, with sallies into countryside to collection folklore and songs, never published; Callanan translations to early number of Blackwood’s Magazine; “Virgin Mary’s Bank” to The Literary Magnet (Jan. 1827), ed. Alaric A Watts, who reprinted it in Poetical Album (1828); ‘Avondhu’ also in Magnet (1827), sign. “Hidalla”; “Gougane Barra” refused by New Monthly Magazine, 1826; variant of familiar version in BL; “Lay of Mizen Head” given to The Harp, 1859, ed. McCann, by John Windele; also lines eulogistic of the author in Patrick O’Kelly, The Aeonian Kaleidoscope (1824); “Cusheen Loo” and “The Lamentation of Felix McCarthy”, cited as his in various collections, disowned explicitly in an MS letter (as above); see D. J. O’Donoghue’s article to this effect in Dublin Evening Telegraph (Jan. 13 & 16, 1890). [PI also cites Michael Francis McCarthy, f. of Justin, and ed. of Poems of J. J. Callanan (n.d.)].

Brian McKenna, Irish Literature, 1800-1875: A Guide to Information Sources (Detroit: Gale Research Co. 1978), writes that Callanan contrib. primarily to Bolster’s Quarterly Magazine, where his “Outlaw of Loch Lene” appeared in a collection of ‘Callanan’s Poetry’ (3, 1828, pp. 191-200) over the words “from the Irish”, and accompanied by a ‘Memoir’ of the poet (pp.280-97).

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects “Dirge of O’Sullivan Bear”, “The Convict of Clonmel”, and “The Outlaw of Loch Lene”. Biog. [FDA2 112], 2 yrs. at TCD as out-pensioner; contracted tuberculosis; went to Lisbon; works incl. The Recluse of Inchidony and Other Poems (London: Hurst, Chance 1839 [err. sic]); Poems of J. J. Callanan (Cork: Bolster 1847); with biog. intro. by M. F. McCarthy; Poems of J. J. Callanan (Cork, Daniel Mulcahy, 1861).

Anthologies: Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (Washington: Catholic Univ. of America 1904), gives eight poems incl. “Dirge of O’Sullivan Bear [sic]”. Charles Gavan Duffy, ed., Ballad Poetry of Ireland, (1848), incls. “Outlaw of Loch Lene” [cited in Dominic Daly, The Young Douglas Hyde, 1974, p.118). Frank O’Connor (Book of Ireland) selects “Gougane Barra” and “Outlaw of Loch Lene”.

Notes

Thomas Kinsella has written: ‘Callanan [then] nothing’. (See Kinsella, ‘The Divided Mind’ in Sean Lucy, Irish Poets in English, 1973, p.212.)

[ top ]