]

|

I

In engaging with Yeats, Joyce and Beckett as the “Major Irish Authors”, we are not merely showing our regard for these three famous men as writers of universally-acknowledged excellence but also engaging with their shared capacity to illuminate Irish historical and cultural experience. More particularly, we are enquiring into the origins and development of a modern tradition of Irish literature in English of which those writers are the chief - but my no means the only, or even the most typical - exemplars. How far international scholars are interested in their “Irishness” is another matter, however it may be noted that most critical writing on Yeats, Joyce and Beckett today is sharply attuned to the Irish background either in itself or as an instance of the post-colonial condition.

In this respect it is their capacity to reflect the realities of the Irish world in unusual depth that holds our attention today in the field of Irish studies. Along with all of this, we ask another question: from what special conditions of the Irish experience of life and art does that capacity stem? This is by no means a simple question although the essential narrative of modern Irish literature is easy to tell. It goes as follows.

W. B. Yeats (1865-1939) may be said to have inaugurated modern Irish literature when he founded the Irish National Literary Society in Dublin in Autumn 1892 - a step which marked the beginning of the Irish Literary Revival, as it was -and still is - generally known. Douglas Hyde, later the first President of independent Ireland, gave the new Society’s inaugural lecture at Yeats’s invitation and, in so doing, he publicised the aim of reviving the Irish language rather than simply encouraging the growth of Irish literature in English.

|

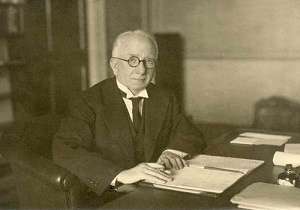

| Douglas Hyde as President of Ireland in 1937 |

Hence the birth of modern Irish literature in English coincides with the attempt to revive Irish literature in Ireland - a complication which has remained intrinsic to the dynamics of the movement for many decades after. In his address to the Literary Society, Hyde spoke about the current state of Irish culture in feisty terms that found a strong echo in the national sentiments of his audience and soon led on to the founding of the Gaelic League in 1893.

| ‘I have no hesitation at all in saying that every Irish-feeling Irishman, who hates the reproach of West-Britonism, should set himself to encourage the efforts, which are being made to keep alive our once great national tongue. The losing of it is our greatest blow, and the sorest stroke that the rapid Anglicisation of Ireland has inflicted upon us.’ (‘The Necessity for the de-Anglicisation of Ireland’, lecture to the National Literary Society, Dublin, Nov. 1892.) |

All of this suggests that Irish (i.e., Gaelic) not English was going to be the language of the Irish literary revival - just as it was much later declared the ‘first national language’ of the Irish State. Hyde’s audience was generally enthusiastic about the repudiation of West-Britonism, though not everyone agreed about the restitution of the Irish language; and it fell to W. B. Yeats to give expression to that qualification in a newspaper letter answering Hyde’s more explicit statement of the case on a subsequent occasion. Yeats tread lightly on this occasion since he had no intention of alienating the support of the Irish-Ireland faction, as the supporters of the Irish language came to be called about that time:

| ‘Can we not build up a national tradition, a national literature, which shall be none the less Irish for in spirit for being English in Language? Can we not keep the continuity of the nation’s life not be doing what Dr. Hyde has practically pronounced impossible but by translating or re-telling in English, which shall have an indefinable Irish quality of rhythm and style, all that is best of the ancient literature.’ (John P Frayne, Uncollected Prose, Vol. I, 1970, p.57.) |

By 1913, the Irish-Ireland campaign had taken on a very conspicuously political character - and, in fact, it had become one of the articles of the Gaelic League which Hyde founded in 1893 and led up to that year that the “aspiration towards national independence” was one of the terms of membership.

|

|

1913 Gaelic League poster by Cesca Chenovix Trench

|

If the Irish language was to gain much ground in the ensuing decades it never did become the dominant language of modern Ireland, nor even of Irish literature - or Anglo-Irish Literature, as it was for a long time known; and to that extent Yeats was the clear winner of the debate. Indeed, his own assertion that ‘there is no great nationality with great literature and no great literature without great nationality’ provided inspiration no less for Irish writers in the English language than for those who wrote in Irish in the years to come. English remained, in effect, the dominant language of intellectual life in Ireland irrespective of the political loyalties of the authors and their degree of talent. And so it still remains.

Nevertheless, the debate between Yeats and Hyde is symptomatic of a fissure within the Irish literary revival itself and it is generally true to say that this fissure or split mapped onto the social divide between the Irish and the Anglo-Irish - though it must be acknowledged that Hyde was, by birth and education, no less an Anglo-Irishman than W. B. Yeats. And this, too, is a recurrent paradox - or seeming paradox - of Irish culture history: the strongest exponents of cultural and political separatism from Lord Edward Fitzgerald to Douglas Hyde have often been Anglo-Irish Protestants, and not Gaelic (‘native’) Catholics at all. This fact can either be regarded as evidence of colonial assimilation to the native culture or, more probably, as the attempt of the colonising cohort to establish their autonomy from the colonial mother country with whom they are dissatisfied, if not positively disgusted.

Inevitably the literature that the Anglo-Irish revivalists produced reflected their own social backgrounds, their prejudices and their idealism - in short, their attitude towards Ireland. It is easy to see in retrospect, for instance, that the Yeatsian project in literary nation-building was essentially conditioned by an anti-modern outlook and especially by his passionate interest in the ‘Heroic Period’ of ancient Irish society rather than the contemporary conditions of modern Irish life - which he famously dismissed with the a strident phrase about ‘the filthy modern tide’. For Yeats the dominant class in contemporary Ireland - Catholic men and women in control of property and business (that is, the emerging middle-class) - were ‘keepers’ of the ‘greasy till’ (caixa) whose spiritual life was a squalid matter of adding ‘prayer to shivering prayer’, as he wrote in his diatribe against them in the poem “September 1913”:

What need you, being come to sense,

But fumble in a greasy till

And add the halfpence to the pence

And prayer to shivering prayer, until

You have dried the marrow from the bone?

For men were born to pray and save:

Romantic Ireland’s dead and gone,

It's with O’Leary in the grave. |

This meant, of course, that if ‘Romantic Ireland’ was to be resuscitated, it would be resuscitated by the Anglo-Irish, not the Irish masses who had betrayed it.

Yeats and many of his followers, including notably John Millington Synge, despised the urban centres and turned instead to Irish peasants living on the Atlantic seaboard, regarding them as a reservoir of myths and legends preserved in their memories and customs long after the destruction of the Gaelic nobility at the Battle of the Boyne. In an alternative interpretation favoured by John Eglinton - a brilliant literary man who opposed Yeats's anti-modern outlook - the truth was simply that the Irish language had helplessly preserved them in its aspic of poverty and defeat, but really both interpretations adverted to the same fact: Ireland was acknowledged to be the premium site of folklore research in contemporary Europe.

For the men and women of the literary revival, as also for the language revivalists, the western peasantry of Ireland was a talisman of authentic Irishness rather than a marginalised population to be despised for its poverty or ‘improved’ by government schemes. The peasant was thus the talisman of the Revival and, to a great extent, the icon of the Independence Movement. Everything was calculated as a “return” to the pristine state of Irish culture as this was to be seen in the simple life of the uncontaminated remnants of ancient Irish culture. Men like Patrick Pearse, the leader of the 1916 Rising - and hence its chief ‘martyr’ - built cottages for themselves in Connemara while artists of the period began to paint the countryside as if it were a sacred landscape.

|

|

| Patrick Pearse |

Lady Augusta Gregory (1852-1932) |

For literary people, it was the stories that that peasants told which was the real treasure - treasures of the mind. Along with Lady Augusta Gregory - another upper-class revivalist and founder of the Irish Literary Theatre - Yeats visited smokey cottages and copied down the stories that were told there. (In reality, Lady Gregory had more nerve in this respect and visited the cottages of her tenants at Coole Park in Co. Galway with a mixture of lordly condescension and real devotion to the business of capturing Irish folklore before it was finally extinguished by emigration or urbanisation - both forms of social hardship in which her own family played a significant contributary role.

|

|

| “Ballad-singer’ by Jack B. Yeats |

“Bog Road” by Paul Henry |

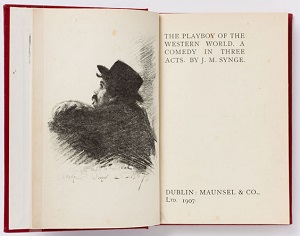

Given, then, their joint-labours in the brick-fields of Irish folklore, Yeats was able to write in “The Municipal Gallery Revisited” (a poem of 1932): ‘we were the last romantics’. Here he is speaking of himself in company with Lady Gregory and John Millington Synge, the first genius of the Irish Literary (later the Abbey) Theatre and author of The Last Playboy of the Western World - a lively comedy about peasant life which remains unfathomable in the complexity of its amo-et-odi attitude towards its subject.

|

|

| Maunsel 1st Edn. and Druid Production (Galway, 2005) |

Synge's play was one of the earliest of Irish peasant dramas - a theatrical genre which would enjoy a long and ultimately a troubled life in the revisionist-versions of the stereotype my our contemporaries such as Brian Friel, Martin McDonagh, and others. The first of the breed was a little one-act play called The Twisting of the Rope by Douglas Hyde - originally as Casadh na Sugain in Irish, produced in October 1901. Together with Yeats's Cathleen na Houlihan (April 1902), this was a testimony to the idealism of the Revival in relation to the poorest class in rural Ireland. Yet by 1904 the Irish peasant was socially and politically extinct in so far as the British Government has passed the Wyndam Act in response to long-standing agitation against landlordism in Ireland. Under the terms of the Act, the former peasants became agricultural proprietors with their own land and soon metamorphosed into a strenous and not-always-indulgent rural bourgeoisie. Those for whom there was no room in the new money-economy of Irish agricultural - that is, those who did not inherit or purchase farms - were doom to emigration (men to labouring jobs, women usually to work as domestic servants).

Thus, almost as soon as the Anglo-Irish and their nationalist partners in the independence movement, started to focus on other Gaelic-speaking Irish peasant as the treasury of Irish culture, that class set out on the road towards its final dissolution.

II

The look that Yeats cast on primitive Irish society was instrincally a “backward look” - in a celebrated phrase coined by the Samuel Ferguson, the 19th-century Protestant scholar and Anglo-Irish poet whom he most admired. (Ferguson is credited with the best - and most authentic - translations of Irish songs yet written at the time.)

Virtually no-one who participated in the Irish Literary Revival looked with affection on Victorian society in Ireland - that is to say, the urbanised world of the emerging middle-class - or sought in it a subject-matter for modern Irish literature. For them, the persistence of the Gaelic past in the rural ares of Ireland provided the best material and their abiding theme. It therefore took a writer very different from Yeats to introduce the world of letters to the empirically life of modern Ireland as it stood in the first years of the twentieth century - and Ireland’s capital Dublin was, in fact, a remarkably modern city at the time, with an advanced public water supply, a electrical transport-system and a network of tele-communications.

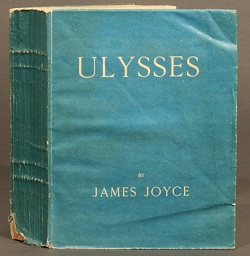

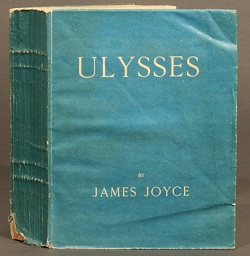

The Irish writer who turned the lens of literary observation on this new world, scorning the romantic ruralism of the Anglo-Irish poets and writers, was James Augustine Joyce (1882-1941). This he did with a vengeance: not only the brick and mortar of Dublin but telephones and trams, love-making and adultery, eating and defecation were all grist to his mill. Together with this, he revolutionised literature by introducing psychoanalytical nightmares in one place and his famous ‘stream of consciousness’ technique of writing in another, which - along with the ‘mythic method’ and his genius for stylistic parody are all part of the shock that he delivered to English literature and the Irish world with his great novel Ulysses.

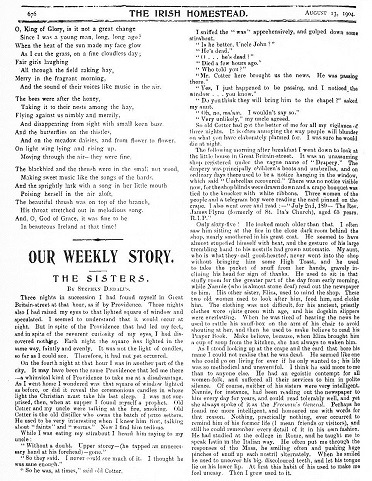

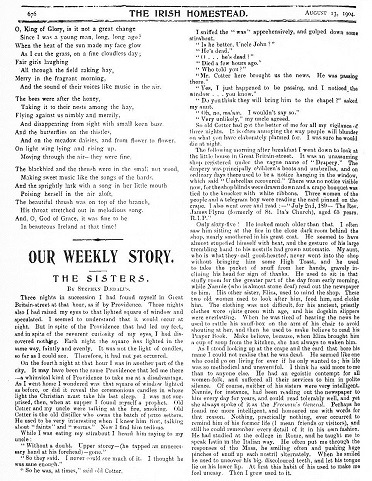

Born to a middle-class Catholic parents - with a mother who claimed descent from Daniel O’Connell - Joyce grew up in a household stricken by his father’s failing fortunes while remaining a brilliant pupil and student at the best schools in Ireland. He developed his own literary and aesthetic philosophy with a considerable show of founding it on Catholic Church Fathers - though it was, in fact, an elegant intellectual pretense which veils much more radical ideas - and never sought to establish any real bond with the leaders of the Literary Revival, taking every opportunity in fact to denigrate and even personally insult them. They returned the favour and the stories that Joyce first published in The Irish Homestead - a journal edited by Yeats’s close associate George (‘‘AE’’) Russell - were equally regarded as a squalid betrayal of the idealism of the period by the revivalists and the Irish nationalists alike. Iin 1904 Joyce left Ireland and lived the rest of his life in Trieste, in Zürich, and in Paris. He thus became the Irish literary exile par excellence.

|

“The Sisters” by Stephen Dedalus [James Joyce]

(Homestead, Aug. 1904). |

Living and writing in those places, Joyce inaugurated what we now think of as Irish realism and produced, in fact, the most advanced form of experimental literature in his time. Yet, though living abroad, his eye remained fixed on Ireland as he had known it before his departure. In Dubliners stories and Ulysses he reconstructed the city with such ‘scrupulous meanness’ that he was able to claim it could be rebuilt stone by stone from the record of his writings. But Joyce was not just a piecemeal realist; he also had epic ambitions and in work after work he proceeded by a process which he once called ‘totalisating’ - that is, building up an encyclopaedic version of reality which stands, in some way, for a form of divine vision or at least a comprehensive expression of the human spirit in all its physical and spiritual relations. Indeed, the most literal and - one might almost say - obsessive of all the Irish major writers in his delineation of the “human comedy” is obviously James Joyce by virtue of the immense scale of his human canvas especially in Ulysses and in Finnegans Wake, works which expressly aim to embrace everything that belongs to human experience.

|

James Joyce’s Ulysses

(Paris: Shakespeare & Co. 1922) |

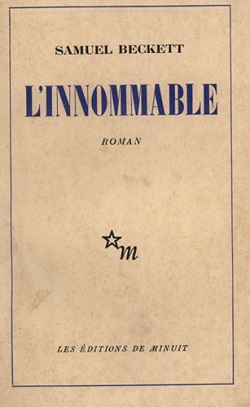

Joyce’s example, both as an Irish writer in exile and one who rejected the romanticism of the literary revival, attracted a brilliant young follower in Samuel Beckett, the author of More Pricks than Kicks (1934) and Murphy (1938) - ingeniously arcane and scabrously amusing fictions set in scenes of Irish low-life and taking Dante, Descartes, and the even more obscure philosophers Schopenhauer and Geulincx, as their intellectual models. Beckett moved to Paris in the 1930s and remained Joyce’s friend and disciple for some years but moved away from him during the climactic experience of isolation and despair in wartime France from which he emerged as the author of a very different kind of fiction that seems to deal with the implosion of human experience into a narrow compass of agonised subjectivity in the midst of an apparently meaningless existence. The chief fruit of this personal ‘excavation’ of the spirit is the trilogy of novels, Malone Dies, Molloy and The Unnamable. These are works of unmitigated sadness, viewed from the standpoint of ordinary hopes and expectations. (We all hope to be happy and often, indeed, expect it.) That, at least, is the common sense of the term “Beckettian” as it is understood in the world of cultural allusions. Yet there hangs a question mark over the final significance of Beckett’s writings - whether they are, in fact, pessimistic or in some paradoxical way an optimistic celebration of the human spirit and the wider spiritual domain from which it might be supposed to stem.

|

L'Innommable (1953)

by Samuel Beckett |

It is now known that the expatriate American writer Henry Miller - a radical ‘sexologist’ in his own right - encouraged Beckett to abandon the Joycean path and find his own way in literature. Beckett was to say later than Joyce’s method of writing was a continual expansion of knowledge whereas his was a continual contraction - an idea which determined his increasingly minimalist way of expressing the reality of human experience. Beckett’s way of writing is the epitome of alienation: the mind stripped of any comfortable reference to the outside world of society and friendship. In this sense it can be regarded as the product of a highly distinctive literary temper combined with brilliantly original literary method. But it can also be related, by way of explanation, to his social origins as a member of the alienated Protestant upper middle-class in post-Independence Ireland. Beckett’s father was a chartered surveyor and he was raised in comfortable surroundings and educated in schools that stood apart from the “real Ireland” of the day - that is, the Irish Catholic majority of Free-State Ireland.

A series of hilarious, malicious and disdainful allusions to that other Ireland in the early fiction reveals Beckett as a young man without a community other than the community of literary minds beyond his native land in time and space. One token of this is the fact that the title-character of the novel Murphy is plagued by the condition of being all mind rather than mind and body comfortably mixed. The place where he finds himself most comfortable is in an lunatic asylum when not in company with his prostitute-girlfriend Celia. The plot and treatment of that first novel can only be regarded as calculated insult directed at the hyper-conservative majority and leadership of contemporary Catholic and nationalist Ireland. At the same time, Beckett was keenly marked by the very thing from which he turned away: the historical experience of misery and oppression which he so brilliantly expressed for modern times in his great agnostic play Waiting for Godot (1952) - a work destined to serve as the epitome of man’s hopeless condition in a world without God in decades after Second World War.

|

|

|

Beckett’s sketchbook for Murphy (1939)

|

Much of Beckett’s literary landscape derives directly from the Irish world but also from Irish literary tradition. His tramps Vladimir and Estragon in that play, for instance, are near relations of the tramps of J. M. Synge’s plays who live survive the hardships of an inhospitable sky by virtue of their exuberant use of language since they possess so little else. For that there is a precedent in Synge: does not Nora say, in The Shadow of the Glen, ‘but you’ve a fine bit of talk, stranger, and its with yourself I’ll go’? Beckett was a profound admirer and a friend of Jack B. Yeats, the poet’s brother and in many ways a figure much closer to J. M. Synge (whose books he illustrated) than to William Butler Yeats.

As regards W. B., though sharing broadly in his class-origins as a middle-class Irish Protestant, Beckett is in every other way his polar opposite. Where Yeats chose to see human imagination in relation to the workings of transcendental mind (or Anima Mundi), for Beckett mind is purely a site of personal torment, a place where time of its very nature imposes interminable hurt on human consciousness and which he makes it his business to record in prose which counts the pulse of mental pain. Yet there is a Beckett beyond this landscape, and criticism often conclude that the antidote to Beckettian horror is Beckettian comedy: in other words, Samuel Beckett achieve transcendence through a form of cosmic laughter - a plausible equivalent to Yeats’s speaking of Buddhist laughter ‘transfiguring all that dread’ (“Lapis Lazuli”).

III

Yeats, Joyce and Beckett - the major Irish writers: all three marked by vastly different temperaments who evolved entirely different literary procedures and displayed hugely different outlooks in their creative lives. Yet, again and again, the elements of common culture and a shared national context serves to reveal their literary careers as variant reactions to the conditions of late-colonial and early post-colonial Ireland, caught up in several kinds of disturbance and upheaval that informed their works in broadly comparable ways. The drama of nation-building is written into all they wrote, even when that drama is expressed as outright rejection of the national entity itself (as in Beckett’s case).

Central to nation-building, as we have seen, is the question of the national language. Is it adequate to say that the language of modern Irish literature is Irish or, alternately, that it is English? No simple answer can be given to this question - not alone since there are both Irish and English-language literatures in modern Ireland, but also because English writing in Ireland involves a version of the language known as Hiberno-English and a version of English literary genres which clearly derives from conditions distinct from those generally prevalent on the other island. Only politically-minded readers have ever asserted the ownership of Irish writing by one language-community or another. In fact, the writings of the major Irish authors all deal more or less directly with the problematic nature of language and the fact that the world is differently constructed by different languages, whether personal or national, cultural or historical.

According to some linguistic thinkers, we - the language-animal - inhabit a “prison-house” in which only reverberations of words already known to us are ever heard. The world is mapped and charted by the meaning-possibilities of our language, or any language we may learn. This doctrine has its depressing side, as speaking of a captivity, but it also has an ecstatic side which we meet with in Yeats’s very early poem, “The Happy Shephard”: where he writes, ‘words alone are certain good’.

|

| Gate Theatre Beckett Cycle (Dublin 2004) |

In All That Fall (1957) one of Beckett’s characters remarks to his middle-aged wife: ‘Do you know, Maddy, sometimes one would think you were struggling with a dead language’, to which she replies: ‘Yes, indeed, Dan, I know full well what you mean, I often have the feeling, it is unspeakably excruciating.’ The problematisation of language, the continual disclosure of elements of difference between one speaker and another as expressed in their way of speaking, these are particularly acute aspects of and Irish literary tradition based, at bottom, on the experience of linguistic displacement from one ‘language’ to another.

It may be, in the end, that the only feature shared by the major Irish writers is a passionate relation to language as language, and to the world that it reveals. In this Module we will closely examine poems, plays and fiction of our three authors and seek to grasp the dynamics of each in their characteristic way of representing reality in words. Widely different as these are, the sense may emerge that a ‘passionate intensity’ in regard to the primary medium of literary art, language itself, is the defining term in the tradition that they share. |