|

| See “The Dead Travel Fast” - A quizzicality about the role of Bürger’s “Lenore” in Dracula - as attached. |

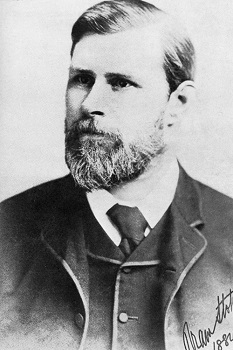

| 1847: b. 8 Nov., 15 The Crescent (Marino; aka Marino Crescent), Fairview [Clontarf], Co. Dublin; bapt. Abraham, 2nd son and 3rd child [of 7] to Abraham Stoker of Derry, petty clerk of Chief Secretary’s Office [who began in post at the Four Courts in 1798], with his wife Charlotte Matilde Blake (née Thornley, 1818-1901; b. Sligo; mar. in Coleraine Parish Church, Co. Derry, 16 Jan. 1844), who had witnessed the cholera epidemic of 1832 in Sligo and was a social reformer in Dublin, concerned with education for the deaf and dumb and other causes; sickly as a child, Stoker was unable to walk until the age of seven, though without any positive diagnosis; ed. at Rev. Woods’ school on Rutland [now Parnell] Sq.; ed. TCD; graduated in Maths, but also studied science, oratory, history and composition; George Ferdinand Shaw (1821-99), founder of the Home Rule League and first editor of The Irish Times, was his tutor; he was also was taught by Edmund Dowden; winner of a Grand Walking Match in Trinity Park with a time of 1 hr. 8 mins., noticed in the Freeman’s Journal, 1 June 1866; grad. with “Double First” (Hons.); elected by turns President of the “Phil” [DU Philosophical Society; by-election of 1870], where he speaks inaugurally on ‘Sensationalism in Fiction and Society’ (1867), and Auditor of the Hist. (1872), lecturing on ‘The Necessity for Political Honesty’ - the only person to hold both positions in the College’s major student societies; becomes a regular visitor to the Wilde’s home at Merrion Sq. (Dublin); describes himself contemporaneously as a ‘philosophical Home Ruler’; responds to Prof. Dowden’s advocacy of Walt Whitman, and writes two lengthy letters of adulation to the American poet praising particularly the idea of manly friendship, the first (1871) remaining unposted for four years; brothers George, Dick and William all trained as doctors; enters civil service, first in Dublin Castle and then throughout the country as Inspector of Petty Sessions; resided with his parents at 8 Harcourt St.; | |||

| 1871: contrib. theatre reviews to Dublin Evening Mail (ed. Henry Maunsell), 1871-75, writing enthusiastic drama criticism; completes extra-mural MA in mathematics (TCD); friendly with John Dillon, and other nationalists; his mother and father departed for retirement to Switzerland; occupies lodgings at 73 Harcourt St., 30 Kildare St., 47 Kildare St., 73 Harcourt St. (again), 119 Baggot St., and 16 Harcourt St. & 7 St. Stephen’s Green; sent Walt Whitman him a letter expressing very great admiration - written four years earlier [as attached]; his first story, “The Crystal Cup”, placed with London Society; receives repeated rejection slips for “Jack Hommon’s Vote”; writes review of Boucicault’s Rip Van Winkle (‘The plot is ... very slight’), and Wilkie Collins' stage-adaptation of his own The Woman in White, both performed in Dublin 1872; contribs. serial stories to The Shamrock incl. “The Primrose Path” (Sept. 1872) - the story of an Irish theatrical carpenter who moves to London for better work; “Buried Treasure” (March 1875), “The Chain of Destiny” (May 1875), a tale of cholera; also “The Dualitists, or The Death Doom of the Double Born” (Theatre Annual, 1887); contribs. unsigned commentaries to The Warder (prop. J. S. Le Fanu at that date); ed. The Irish Echo, a Dublin evening paper based on London morning papers; suffered death of father, in Switzerland, Oct. 1876; organises reception for Henry Irving [bapt. John Henry Bobdribb] in Dublin, 1876, including a “College Night” at the theatre and a popular procession through the city in which the actor’s carriage was drawn by the students; meets Irving, 3 Dec. 1876, and forms a close bond; organises further Dublin visits for Irving; writes ‘London in view!’ in diary, 22 Nov. 1877; living above a grocer shop at 7, St Stephen’s Green in 1877; | |||

| 1878: issues Duties of the Clerks of Petty Sessions in Ireland (1878); moves to London as Irving’s mgr. (‘Irving’s treasure’ to some but is ‘literary henchman’, acc. George Bernard Shaw); opens The Lyceum in collaboration with H. J. Loveday (its former stage-manager), thus forming ‘the Unholy Trinity’ that would dominate London stage, 1878-1905; the first to put numbers on theatre seats; commences flirtation with the American actress Geneviève Ward who appeared on the Irish stage - and with whome he had had a long flirtation including an invitation from her to stay in Paris; meets Sir Richard Francis Burton on the boat train to Dublin 1879; courts Florence Anne Lemon Balcombe, the friend of Oscar Wilde (who called her ‘Florrie’ and requested back from her the gold cross he had given); m. at St. Anne’s Church, Dawson St., Dublin, 4 Dec. 1878, she being cited on the certificate as a minor; settles at 7, Southampton St., Covent Gdn., London (unfurnished rooms, £100 p.a.); Florence refuses sex after the birth of the first and only child, [Irving] Noel Thornley Stoker, in 1879 (according to Enid Stoker, gm. of biographer Daniel Farson); family moves to 27, Cheyne Walk, Chelsea, 1881, Stoker cycling from there to work at the Lyceum Theatre off the Strand; rescues a suicide from drowning in the river, 13 Sept. 1882, the old man later dying on the Stoker’s dining table, causing Florence to hate the house [var. recovered the body from the river]; moves to 17 St. Leonard’s Terrace; received a medal for courage; | |||

|

|||

| 1882: ssues Under the Sunset (1882), a novel, and “Lies and Lilies” (1882), a story; includes a tale of disease destroying a whole land; brings Lyceum on first tour of America, taking Boston Theatre, 1883; visits Walt Whitman at his home, 20 March 1884 (the man ‘fulfils the boy’); visits Quebec, Sept. 1884; lectures on “A Glimpse of America”, 28 Dec. 1885; sails for America to arrange further Lyceum tour with Irving’s sensational version of Faust, Autumn 1886; Florence and Noel escape from shipwreck on board steamship “Victoria” nr. Dieppe, 13 April 1887; Stoker lectures in Lincoln [Th.] at Chickering Hall, New York, 25 Nov. 1887, using Whitman’s “Memoranda During the War” as source; occurrence of ‘Jack the Ripper’ murders, Whitechapel, 1888 (once linked by Stoker to his famous novel in an introduction); met Ellen Terry when she joined the company in 1888; visits Whitman for the last time and tries to persuade him to expurgate homosexual references in Leaves of Grass; partly rewrote Vanderdecken, stage-version of the Flying Dutchman legend with Irving in the lead role - being the play that Jonathan Harker is going to see in Dracula in an original section later cut from the novel; | |||

| 1896: travels to USA with Irving, winter 1896; feuding between Irving and Shaw; on 20 May 189[6] signs contract with Archibald Constable (2 Whitehall Gdns. Westminster) for a novel provisionally called “The Un-dead” and inspired by ancient tales of vampirism and some contemporary reportage of 1887 but also heavily influenced by “Carmilla”, the vampire tale by J. S. Le Fanu whose example Stoker had already followed in “The Chain of Destiny” (Shamrock, 1875); a typescript of the novel published as Dracula by Arthur Constable and Company, in mustard-yellow cloth boards, on 26 May 1897; borrows a substantial sum from his close friend the novelist [Sir Thomas] Hall Caine - the “Hommy Beg” of the dedication in Dracula; dramatic copyright protected by an advertised reading at Lyceum on morning of 18 May 1897, with Ellen Terry’s daughter (one of two), reading the part of Mina - a matter of four hours; Dracula published 24 June 1897; Irving repeatedly refuses to play part of Dracula; the Stokers move to 18 St Leonard’s Terrace, Chelsea, London; [seemingly] presents the typescript of Dracula to the unknown American who partly inspired it by providing vampire-material from The World (NY) in 1896; Lyceum scenery destroyed in storage by fire, 18 Feb. 1898; Irving falls ill with pleurisy, and signs away The Lyceum to a consortium [joint stock company] without consulting Stoker, 1899; Stoker writes a cryptic biographical notice on himself for Who’s Who (under recreations, ‘pretty much the same as those of the other children of Adam’); departs aboard SS Marquette on US tour, Oct. 1899; Dracula went into a 6p. Popular Edn. in 1901; | |||

| 1902: death of Charlotte Stoker, 1902 (bur. St. Michan’s, Dublin); Stoker becomes increasingly alienated from Irving following the latter’s marriage to Eliza Aria; spends summers at The Crookit Lum (cottage), in Cruden Bay, and writes The Mystery of the Sea there, a novel involving ghosts [revenants] and cypher, 1902; visits America for the second time with Irving and the Lyceum Company, a party of 82, sailing out on the SS Minneapolis (Atlantic Transport Line), Oct. 1903, returning April 1904; issues The Jewel of the Seven Stars (1903), a novel with an Egyptian mummy plot, ded. to Eleanor [viz, Elinor Wyle] and Constance Hoyt, two beautiful American girls who visited London; issues The Man (1905), in which Harold An Wolf, a Cambridge grad. and Alaskan adventurer, is matched with Stephen Norman, a ‘New Woman’; Irving collapses and dies in the arms of his dresser after a performance [var. his Bradford hotel bedroom]; of his own adaptation of Tennyson’s Becket during his ‘farewell’ tour in Bradford, Friday 13 Oct. 1905 (bur. Westminster Abbey); Stoker returns to journalism; contribs. interviews to The Daily Chronicle; issues Personal Reminiscences of Henry Irving, 2 vols. (1906), better received than any of his fiction though afterwards trashed by Austin Brereton in his life of Irving (1908); briefly returns to theatre management for David Bishopham’s musical performance of The Vicar of Wakefield, 1906; organises English section of Paris Theatrical Exhibition; appears as model for William II Building the Tower of London in Goldsborough Anderson’s mural in the Royal Exchange (London); club & society membership included Dramatic Debaters, Society of Authors, Shakespeare Memorial Soc., Urban Club, and New Vagabond Club (with Hall Caine); contribs. ‘Fifty Years on Stage: An Appreciation of Ellen Terry’ to The Graphic in her jubilee year, 1906; experiences declining health from 1905; | |||

| 1907: suffers a minor stroke, being nursed by Florence; moves to 4 Durham Place, Chelsea (in the former home of Captain Bligh), 1907; joins the staff of Daily Chronicle; contribs. theatrical profiles to World (NY); participates prominently in campaign to censor ‘unclean’ books; writes “The Censorship of Fiction” for The Nineteenth Century & After, and “The Censorship of Stage Plays”, the latter warning against decentralisation of the Lord Chamberlain’s duties among to local authorities; contribs. “The Great White Fair in Dublin” and “The World’s Greatest Ship-building Yard” [Harland & Woolff, Belfast] to an ‘Irish Number’ of The World’s Work (Vol. 9, 1907); issues Famous Impostors (1910), which includes the assertion that Elizabeth I was a man in disguise; issues The Lady of the Shroud (1909), a novel ded. to Geneviève Ward - the American actress with whom he had had a long flirtation with letters exchanged from 1875; suffers second stroke and receives £100 [pension], 1910; his son Noel T. Stoker marries Neelie Moseley Deane Sweeting, 30 July 1910; seeks grant from Royal Literary Fund, 1911; becomes member of National Liberal Club; moves to 26, St. George’s Sq., Belgravia; issues The Lair of the White Worm (1911), in which the worm, Lady Arebella, is eradicated by the hero Adam Salton, with much sexual symbolism [tunnels, &c.]; defends Capt. E. J. Smith of the Titanic, which sank on 15 April; Stoker d. 20 April; death cert. admitting interpretation of syphilis (disputed by Belford); cremated and bur. at East Columbarium, Golders Green, London, where his wife’s ashes were afterwards distributed; obits. appeared in London Times and Irish Times, 22 April 1912, the latter calling him ‘a typical Irishman of the best type’ and citing novels ‘of a sensational character’ without naming Dracula); | |||

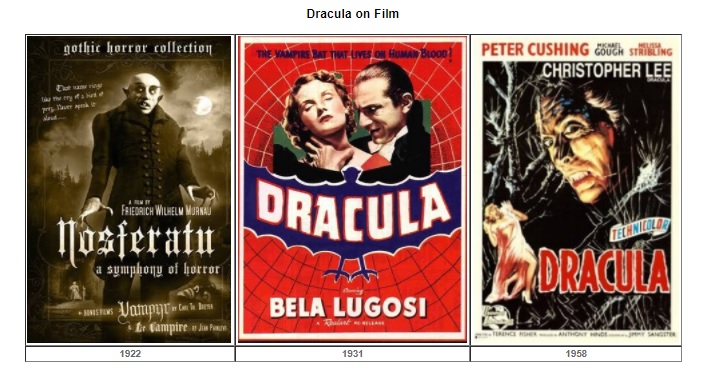

| Posthumous: Florence Stoker sells 317 items of his literary effects at Sotheby’s, 7 July 1913; moves to 4 Kinnerton Studios (now Braddock Hse.), Knightsbridge, 1914; issues Dracula’s Guest, a chapter excluded from the 1897 novel [and still omitted], dealing with a Jonathan Harker’s encounter with a vampiric femme fatale on his way to Dracula’s castle; also incls. “The Judge’s House”, dealing with the nervous breakdown of the title-character; Mrs. Stoker donates relevant papers to Irving Collection at Stratford-upon-Avon; she strenuously contests the rights of Prana Films version of Dracula, directed by F[riedrich] W[ilhem] Murnau as Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922), through the Society of Authors, resulting in ostensible destruction of the unauthorised film, July 1925 - featuring Max Schreck as the first screen Dracula; the first dramatic production of Dracula was directed by Hamilton Deane, Little Theatre, 14 Feb. 1927; filmed for Universal Studios by Tod Browning with Bela Lugosi in lead (later buried in his Dracula cloak), 1931; first filmed in colour by Hammer Films with Christopher Lee as Count Dracula and Peter Cushing as Van Helsing, 1958 - to be followed by numerous Lee sequels; skit-version filmed by Roman Polanski, as Dance of the Vampires, with Sharon Tate, in 1967; Vampires in New York, an AIDS-themed Dracula, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, with Brad Pitt, 1997; the Dublin diaries of Bram Stoker were discovered by a grandson, Noel Dobbs, in family papers in the Isle of Man; | |||

| the first full biography issued by Harry Ludlam (1962), after which another by Stoker’s grand-nephew Daniel Farson (1975), alleging that his death was caused by syphilis; another issued by Barbara Belford (1996); the working papers for Dracula are held in Philadelphia; an archive of Stoker family papers was presented to TCD Library by Noel Dobbs, Aug. 1999; new biography issued Paul Murray (2004), with much new material from papers of Sir Thornley Stoker - who was the object of well-known comments by George Moore; four new Irish stamps were issued to commemorate Stoker in 2004; Google celebrated his 165th birthday with a Stoker “doodle” [online]; a Lost Journal of 1871-81, discovered in the attic of the writer’s great-grandson Noel, was edited by Dacre Stoker and Catherine Wynne [Hull Univ.] in 2012, revealing Stoker’s first researches into European folklore - and incidentally demonstrating that Vlad the Impaler was not among the founding inspirations of the novel Dracula, though Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams was; his brothers Richard and George both graduated in medicine at the Royal College of Surgeons of Ireland; his younger br. Thornley Stoker (1845-1912; baronet, 1911) - who receives a mention in Joyce’s Ulysses - held the chair of Anatomy at the RCSI anatomist and a medical writer and served as President of the RCSI during 1903-06; a Bram Stoker Society & Summer School [BSSSS] is held annually in Ireland, chaired by Leslie Shepard, 1 Lakelands Close, Stillorgan, Co. Dublin; Stoker is almost exclusively remembered for Dracula which has increasingily come to be regarded as a ‘queer-coded’ book in which homosexual and otherwise transgressive behaviours are both relished and anathemised. IF JMC DIL DIW DIB OCEL KUN SUTH FDA OCIL |

[ top ]

| For access to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) - see infra |

| Fiction | ||

|

||

| Collections | ||

|

||

|

||

| Miscellaneous | ||

|

||

| Journal contribs. | ||

|

||

| [ top ] | ||

| In translation | ||

|

||

| Critical Editions | ||

|

||

| Diary, Manuscripts and Notes | ||

|

||

| Reprint Editions (sel.) | ||

| Dracula | ||

|

||

| Further compilations | ||

|

||

|

||

| Other titles | ||

|

||

| Bibliography | ||

|

||

| Irish Adaptions | ||

|

The Gutenberg Project Online editions of Stoker’s works at the Gutenberg Project incl. Dracula [text & audio]; Dracula’s Guest; The Lady of the Shroud; The Jewel of Seven Star; The Man; The Lair of the White Worm. See Gutenberg’s Stoker list - online [last access - 04.10.2107.

[ top ]

| The Complete Works of Bram Stoker (London: Delphi Classics [Ser. 2] 2009), 368pp. | |

|

|

| Published 2014; available online. | |

|

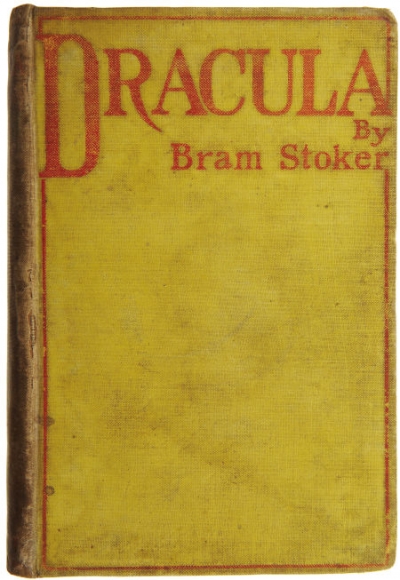

| Dracula (1st edn. 1897) - with distinctive its mustard-yellow cloth-on-boards cover. |

[ top ]

| Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897) - The RICORSO Edition | |||||||||||||

| Index of Chapters | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | - |

[ The above index opens individual chapters of Dracula within the current frame. To access the edition in a separate window - i.e., without the Ricorso frame - click here. ] |

|||||||||||||

| Full-length studies | Articles & Intros. | Vampire Studies | Dissertations, &c. |

| Full-length Studies |

|

| [ top ] |

| Articles & Introductions |

|

| [ top ] |

| Gothic, ‘Vampire’ & Gender & Genre Studies |

|

| Irish Gothic & Post-Colonial Theory |

|

See also Noel Carroll, The Philosophy of Horror (NY: Routledge 1990); Patrick Brantliger, Rule of Darkness (Cornell UP 1998); Karl Beckson, London in 1890s: A Cultural History (NY: W. W. Norton 1992). |

| Dissertations (Selected) |

|

| Bibliography |

|

| See The Bram Stoker Society Journal. |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

William Hughes & Andrew Smith, eds., Bram Stoker: History, Psychoanalysis and the Gothic History (Basingstoke: Macmillan 1998), 229pp., CONTENTS: Preface; Acknowledgements; Notes on the Contributors; Smith & Hughes, Introduction: ‘Bram Stoker, the Gothic and the Development of Cultural Studies’; Alison Milbank, ‘“Powers Old and New”: Stoker’s Alliances with Anglo-Irish Gothic’ [pp.12-28]; C. C. Simmons, ‘Fables of Continuity: Bram Stoker and Medievalism’; M. Kilgour, ‘Vampiric Arts: Stoker’s Defense of Poetry’; Robert Mighall, ‘Sex, History and the Vampire’; M. Mulvey-Roberts, ‘Dracula and the Doctors: Bad Blood, Menstrual Taboo and the New Woman’; Robert Edwards, ‘The Alien and the Familiar in The Jewel of Seven Stars and Dracula’; Victor Sage, ‘Exchanging Fantasies: Sex and the Serbian Crisis in The Lady of the Shroud’; Lisa Hopkins, ‘Crowning the King, Mourning his Mother: The Jewel of Seven Stars and The Lady of the Shroud’; Joseph S. Bierman, ‘A Crucial Stage in the Writing of Dracula’; David Punter, ‘Echoes in the Animal House: The Lair of the White Worm’; D. Seed, Eruptions of the Primitive into the Present’: The Jewel of Seven Stars and The Lair of the White Worm’; Jerrold E. Hogle, ‘Stoker’s Counterfeit Gothic: Dracula and Theatricality at the Dawn of Simulation’; Index.William Hughes, Bram Stoker’s “Dracula”: A Reader’s Guide to Essential Criticism (London: Continuum 2009), 176pp. CONTENTS [Chapters]: Psychoanalysis and Psychobiography: The Troubled Unconsciousness of Dracula; Medicine, Mind and Body: The Physiological Study of Dracula; Invasion and Empire: the Racial and Ccolonial Politics of Dracula; Landlords and disputed Territories: Dracula and Irish Studies; Assertive Women and Gay Men: Gender Studies and Dracula.

William Hughes, Bram Stoker: Dracula [Consult. ed. Nicholas Tredell] (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2009) - CONTENTS Chap. 1. Psychoanalysis and psychobiography; Chap. 2. The Troubled Unconscious of Dracula; Chap. 3. Medicine, Mind and Body: the Physiological Study of Dracula; Chap. 4. Invasion and Empire: The Racial and Colonial Politics of Dracula; Chap. 5. Landlords and Disputed Territories; Chap. 6. Dracula and Irish Studies; Chap. 7. Assertive Women and Gay Men; 8. Gender Studies and Dracula.].

Also as Hughes, Bram Stoker: Dracula [consult. ed. Nicholas Tredell] (London & NY: Palgrave Macmillan 2009), x, 173pp. CONTENTS: 1. Psychoanalysis and psychobiography; 2. The Troubled Unconscious of Dracula; 3. Medicine, Mind and Body: the Physiological Study of Dracula; 4. Invasion and empire: The Racial and Colonial Politics of Dracula; 5. Landlords and disputed territories; 6. Dracula and Irish studies ; 6. Assertive women and gay men; 7. Gender studies and Dracula. [cited in COPAC - online; accessible Google Books - online].

Glennis Byron, ed., Dracula: Bram Stoker [New Casebooks] (Basingstoke: Macmillan 1999), ix, 225pp. CONTENTS. Acknowledgements General Editors’ Preface. Byron, Introduction; D. Punter, Dracula and Taboo; Phyllis A. Roth, Suddenly Sexual Women in Bram Stoker’s Dracula; Franco Moretti, Dracula and Capitalism; E. Bronfen, Hysteric and Obsessional Discourse: Responding to Death in Dracula; R. A. Pope, Writing and Biting in Dracula; Christopher Craft, ‘Kiss Me with Those Red Lips’: Gender and Inversion in Bram Stoker’s Dracula; Stephen D. Arata, The Occidental Tourist: Dracula and the Anxiety of Reverse Colonization; N[ina] Auerbach, Dracula: A Vampire of Our Own; Judith Halberstam, Technologies of Monstrosity: Bram Stoker’s Dracula; David Glover, Travels in Romania: Myths of Origins, Myths of Blood; Further Reading; Notes on Contributors; Index.

John-Paul Riquelme, ed., Dracula: Complete Authoritative Text with biographical, historical, and cultural contexts, critical history, and essays from contemporary critical perspectives [Case Studies in Contemporary Criticism] (Basingstoke: Palgrave 2002), xv, 622pp. CONTENTS. Pt. 1 - THE COMPLETE TEXT IN CULTURAL CONTEXT: Biographical and Historical Contexts; The Complete Text (1897); Cultural Documents. Pt. 2 - A CASE STUDY IN CONTEMPORARY CRITICISM: A Critical History of Dracula; Sos Eltis, Gender Criticism and Dracula; D. Foster, Psychoanalytic Criticism and Dracula; Gregory Castle, The New Historicism and Dracula; J-P. Riquelme, Deconstruction and Dracula; Jennifer Wicke, Combining Critical Perspectives on Dracula; Glossary of Critical and Theoretical Terms; About the Contributors; Index.

Catherine Wynne, Bram Stoker, Dracula and the Victorian Gothic Stage (London: Palgrave Macmillan 2013). CONTENTS [Chapters]: Introduction: Setting the Scene, [1]; 1. Stoker, Melodrama and the Gothic [12]; 2. Irving’s Tempters and Stoker’s Vanishing Ladies: Supernatural Production, Mesmeric Influence and Magical Illusion[41]; 3. Ellen Terry and the “Bloofer Lady”: Femininity and Fallenness [78]. 4. Gothic Weddings and Performing vampires: Genevieve Ward and The Lady of the Shroud [107]; 5. The Lyceum Macbeth and Stoker’s Dracula [131]; Conclusion [161-70]. [See Palgrave - online; also available at Google Books - online; accessed 04.10.2107.]

See Tracy C. Davis, review of Wynne, ed., Bram Stoker and the Stage, in Times Literary Supplement (23 Jan. 2013) - online [a scholarly account of Stoker’s experience of Dublin theatre as derived from his Mail reviews and his management of Irving’s Lyceum Th. in London.]

Jarlath Killeen, Gothic Literature 1825-1914 [History of the Gothic] (Cardiff: University of Wales Press 2009), 248pp. Contents. Series Editors' Foreword [vii]; Acknowledgements [viii]; Introduction 1]; 1. The Ghosts of Time [27]; 2. The Horror of Childhood [60]; 3/ Regional Gothic [91]; 4. Ghosting the Gothic and the New Occult [124]; Conclusion: Moving to the Gothic Trenches [16]; Survey of Criticism [166] Gothic Chronology [187]; Endnotes [199]; Bibliiography [219]; Index [241].

Jarlath Killeen, ed., Bram Stoker: Centenary Essays (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2013), 206pp. CONTENTS: [Killeen,] Introduction: Remembering Bram Stoker David J. Skal, “Bram Stoker: the child that went with the fairies “; Paul Murray, “Bram Stoker: the facts and the fictions “; Elizabeth Miller, “Bram Stoker: a man of notes’; Carol A. Senf, “Bram Stoker: Ireland and beyond’; Andrew J. Garavel, “The shoulder of Shasta: Bram Stoker’s California romance’; William Hughes, “‘Rumours of the great plague”: medicine, mythology and the memory of Sligo cholera in Bram Stoker’s Under the Sunset’; David Floyd, “‘The sport of opposite forces”: Bram Stoker’s generational anxiety’; Valeria Cavalli, “‘See how the bog can preserve”: bogs, snakes and Irish stereotypes in The Snake’s Pass’; Darryl Jones, “The lair of the white worm; or, What became of Bram Stoker?’; Christopher Frayling, “Mr Stoker’s holiday’.

Studies of Gothic Literature by Jarlath Killeen Gothic Ireland

(2005)Gothic Literature 1825-1914

(2009)Emergence of Irish Gothic Fiction

(2013)Bram Stoker: Centenary Essays

(2013)

[ top ]

Commentary

See separate file [infra].

[ top ]

Quotations

See separate file [infra].

[ top ]

| See Stoker websites - as infra |

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washington: University of America 1904); gives ‘The Gombeen Man’, excerpted from The Snake’s Pass.

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919); ’a tale ... about the strange phenomenon of a moving bog in Mayo, with hidden treasure and prophetic dreams, attempted murder, love-sentiments, and no sectarian bias; chars., Andy Sullivan the carman, and a priest, Father Pether’. Bibl, incl. Under the Sunset (1882); The Shoulder of Shasta (1895); The Watter’s Mou (1895); Dracula (1897), translated into Irish by Sean Ó Cuirrin (Oifig Diolta Foillseacháin Rialtais, 1933), and dramatised by H. Dean and J. J. Balderston (Samuel French [1933]); Miss Betty (1898); Lady Athlyne (1908); Snowbound, the Record of a Theatrical Touring Party (1908); The Lair of the White Worm [1911]; Dracula’s Guest, and Other Weird Stories (1914).

John Sutherland, The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (Harlow: Longmans 1988); lists Dracula (London: Constable 1897), which Stoker claimed came from a nightmare though the more plausible source is Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872); paraphrase only. Main Entry, b. Dublin, son of minor civil servant, childhood illness; TCD 1864-68; pres. Phil.; and athlete; Inspector of Petty Sessions of Ireland, 1877-78; his first horror story, ‘The Chain of Destiny’ appeared in Shamrock 1875; affiliated to Whitman vogue; f. of Henry Irving; m. and resigned civil service, 1878; bus, mgr for Irving’s London Lyceum; served Irving 27 years; reminiscences, 1906; Under the Sunset (1881), ‘fairy tales’; Dracula dedicated to Hall Caine; cultivated Conan Doyle and Oscar Wilde, whose former intended Francis Balcombe he married; first novel, The Snake’s Pass (1890), adventure, mystery and lost treasure in the west of Ireland; Dracula (1897)six eds. in first year; Lyceum burns down, also 1897; romantic Miss Betty (1898); The Jewel of Seven Stars (1903), Egyptian reincarnation; The Lady of the Shroud (1909), vampire; The Lair of the White Worm (1911), allegorical and supernatural. His most anthologised story is “The Squaw” [1893], in which an Indian spirit pursues a man to his eventual death in a Nuremberg torture chamber. BL 12.

Robert Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1979); his mother, an influence, was a woman of great energy, breathless disposition, and reckless housekeeping; his father was a civil servant [var. solicitor: OCIL]; served as Irving’s indefatigable secretary and manager at the London Lyceum Theatre; married Oscar Wilde’s sweet-heart Florence Balcombe, who became frigid after childbirth; womaniser, died of syphilis. Non-fiction works incl. Famous Imposters (1910), propounding the theory that Queen Elizabeth was a man in disguise. Justly forgotten novel, The Snake’s Pass (1891) about Ireland.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects Dracula pp.889-98; W J McCormack, ed. ‘Irish Gothic and After, 1820-1945’, pp.842-46,’ Stoker rarely refers in his fiction to Ireland or its surviving folk traditions. True, his first novel, The Snake’s Pass (1891), is set in Co. Mayo, abounds in sentimental violent incident, and even summons up legends of the French revolutionary invasion; true also that Dracula was also eventually translated into Irish in 1933, perhaps to mark the accession to power of Eamon de Valera. Essentially Stoker aligns himself with the London exiles [..] as against the home-based revivalists, and the gross primitivism of his best-known fiction indicates a compensatory mechanism at work in this dichotomy of the metropolitan and the provincial, [831; also, 837, 838, 841, 842-46, 852];, 955; [Bram Stoker (sic err.) translated into Irish, 948, see infra], BIOG, In relation to his Irish origins one should note that The Snake’s Pass (1891) is ostensibly set in rural Ireland, and that Dracula was translated into Irish by Seán Ó Cuirrín (Oifig Diolta Foillseacháin Rialtais 1933); his br. Sir Thornley Stoker was sometime president of the Royal Coll. of Surgeons [and occurs as a shadowy character associated with a house full of antiques in George Moore’s Hail & Farewell; see FDA2 note at 948 only (Bram Stoker biog.)]. Criticism as supra. See also remark of W J McCormack: ‘Dracula was also eventually translated into Irish in 1933, perhaps to mark the accession to power of Eamon de Valera.’ Further: Writing in 1938 about the threat posed by Anglo-American popular culture to Irish identity, Michael Tierney could state that, ‘the difficulty in which we find ourselves is only made more apparent by the belief that the Gaelic cause is advanced when H. G. Wells, Bram Stoker, and the latest American song-numbers are translated into the Irish language’ (Tierney, ‘Politics and Culture, Daniel O’Connell and the Gaelic Past’, in Studies, Vol. 27 (1938), pp.358-59) [955]

Brandon Press Catalogue (1990) lists Dracula [1897]; The Snake’s Pass [1890]; Dracula’s Guest [1914]; and The Lair of the Worm [in which the new Independent Woman is not just a vamp but a vampire, see Brandon Cat. 1994/5]. The publisher’s blurb describes The Snake Pass as his first novel and only Irish one, a tale revolving round a villainous ‘gombeen-man’, in his own way as evil as Count Dracula [which] suggests that the novel may be significant as a reflection on the Irish politico-economic situation of the day.

[ top ]

| Some Stoker websites ... | |||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

[ top ]

Notes

Lair of the White Worm (1911): Adam Salton is contacted by his granduncle Richard Salton who seeks to purpose establish a relationship with the last member of his family. Adam, and travels to the other’s house in Mercia where he finds himself caught up in strange events involving Edgar, the heir to the Caswall estate, who has been mesmerising a local girl, while Arabella March, a lady in the vicinity, appears to aim at seducing Edgar and becoming Caswall for the furtherance of her dark intents. The destruction of the worm’s lair in its hidden cavern within the sea-cliff, along with its human priestess (Lady March), provides an the explosive climax for the novel. Mimi and her ‘stalwarth’ fiancé Adam go on honeymoon at the conclusion of the novel.

|

[ top ]

William Carleton: Carleton includes a reference to vampirism in The Black Prophet (1847) - as recounted by Pat Sheeran: ‘In the opening scene of the book Donnel’s daughter is shown sinking her teeth into her stepmother, yet another baleful figure, and the narrative likens the action to “[...] the fierce play of some beautiful vampire that was ravening for the blood of its awakened victim”’. (The Black Prophet, London 1899, p.7; see Sheeran, “The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty: A Study in Romantic Realism” [Ph.D. Diss.], UCG 1972, p.188.)

Archbishop Paul Cullen: ‘Nothing good can be effected for Ireland, until something shall have been done to prevent the ravages of an infidel and revolutionary [organisation] subsidised, and maintained to a great extent by foreign gold.’ (Quoted in Oliver Rafferty, S.J., ‘The Catholic Church and Fenianism, 1861-1870: Some Irish and American Perspectives’, in Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, Winter 1997/Spring 1998, pp.47-69; p.57.)

W. B. Yeats: ‘Yeats knew Stoker; he inscribed a copy of The Countess Kathleen to him in 1892 [Berg Coll., NYPL], read Dracula with Ezra Pound, and was only put off a proposed visit to Dracula’s original castle (though Yeats thought it was in Austria, not Transylvania) by the outbreak of a world war in 1914.’ (See R. F. Foster, ‘Protestant Magic: W. B. Yeats and the Spell of Irish History’ [rep.] in Jonathan Allison, ed., Yeats’s Political Identities, Michigan UP 1996, p.91.

Emily Lawless: Jin Liu, in ‘Emily Lawless: A Prose Writer’ (MA Diss., UUC 2003), discussing the title-character of Lawless’s novel Maelcho (1894), who is described as a “Child-man” (p.355) - thus anticipating the usage that Stoker applies to Count Dracula [see infra].

Thornley Stoker [Sir], br. of Bram Stoker was ‘on the look-out for a post in a Museum’, according to George Moore (Vale, 1914, p.123; quoted in Adrian Frazier, ‘Napoleon in a Dress: Robert O’Byrne: Hugh Lane’, in The Irish Review, No. 25 (Summer 2001), p.179 [n.2].

Cesare Lombroso (1836-1909) - founder of the Positivist Criminology; issued work L’Uomo Delinquente (1876) - trans. as Criminal Man; launched the idea of the ‘born criminal’ who was marked by ‘physical and psychological anomalies’ - including the hypothesis that ‘epilepsy frequently reproduced atavistic characteristics, including even those common to lower animals’. (See excerpts at Manybooks - online - where it is styled a ‘pseudo-scientific analysis of the nature of crime’.

Lombroso: ‘The idea first came to me in 1864, when, as an army doctor, I beguiled my ample leisure with a series of studies on the Italian soldier. From the very beginning I was struck by a characteristic that distinguished the honest soldier from his vicious The first idea came to me in 1864, when, as an army doctor, I beguiled my ample leisure with a series of studies on the Italian soldier. From the very beginning I was struck by a characteristic that distinguished the honest soldier from his vicious comrade: the extent to which the latter was tattooed and the indecency of the designs that covered his body. This idea, however, bore no fruit. [...].’ (See further extracts from Criminal Man according to the classification of Cesare Lombroso briefly summarised by his daughter Gina Lombroso Ferrero, with an introduction by Cesare Lombroso (NY: Putnams/Knickerbocker Press 1911) - as attached.)

Bibl. Criminal Man, According to the Classification of Cesare Lombroso, B Summarised by his Daughter Gina Lombroso Ferrero with an Introduction by Cesare Lombroso [The Knickerbocker Press] (NY & London: G. P. Putnam’s Sons 1911), 322pp. [Index, p.315ff.]

Further [Criminal Man, “Atavism and Punishment”, being Chap. II]: ‘Those who have read this far should now be persuaded that criminals resemble savages and the colored races. These three groups have many characteristics in common, including thinness of body hair, low degrees of strength and below-average weight, small cranial capacities, sloping foreheads and swollen sinuses ... These facts clearly prove that the most horrendous and inhuman crimes have a biological, atavistic origin in those animalistic instincts that, although smoothed over by education, the family, and fear of punishment, resurface instantly under given circumstances.’ (Duke Edn. 2006, p.91; quoted in Gary McKay; UG Diss. UUC 2012.)

Cesare Lombroso (1836-1909) - see remarks in Ann Saddlemyer, Becoming George: The Life of Mrs W. B. Yeats (OUP 2002): ‘Grief [at the death of her father] may well have led her to Cesare Lombroso’s recently translated apologia, After Death - what? Spiritual Phenomena and their Interpretation, which she had read in 1902. However, with her usual diligence she pursued the study of spiritualism far beyond the French psychiatrist’s somewhat naive and heavy-handed discussion of conversion to belief in the reality of thought transference and finally, through experiments with the medium Eusapia Paladino, phantasmic activity and reincarnation. (Ironically Lombroso, who held the chair of criminal anthropology at the University of Turin, began his career as a sceptical scientist concentrating on the study of cretins and criminals in an attempt to establish a theory of degeneracy; by examing their brain structure, he concluded too that women are natural criminals.)’ (p.43.)

Cf. Van Helsing: ‘The Count is a criminal and of criminal type. Nordau and Lombroso would so classify him, and qua criminal he is of imperfectly formed mind.’ (Dracula, p.406). [See also under James Joyce, infra.]

Max Nordau - see Marjorie Howes, Yeats’s Nations: Gender, Class, and Irishness (1996), Chap. I: “That sweet insinuating feminine voice [....; &c.]’: ‘[...] Sexual pathology and effeminacy were central to contemporary descriptions of decadence, as were the decadent’s similarities to the perceived depravities of the New Woman. Freud and Breuer notwithstanding, the Celt’s hysteria and decadence were also culturally linked to some late nineteenth-century theories of degeneration; as Daniel Pick has argued, such theories expressed fears about too much progress and civilization as well as too little [Faces of Degeneration: A European Disorder, c1848-1918, Cambridge UP 1989. Many of [Matthew] Arnold’s Celtic traits were also the same qualities that were to characterize Max Nordau’s 1895 portrait of the decadent artistic degenerate. Although Nordau [in Degeneration, London: William Heinemann 1913] acknowledged that degeneration afflicted both men and women, its symptoms, which resemled and often occurred in conjunction with those of hysteria, were particularly feminine. Arnold’s feminization of the Celt found further echoes in the work of Otto Weineger, whose “anti-feminine” and racist theories involved extensive comparison of Jews and women in his influential book Sex and Character (1903). Like Arnold, Weininger linked femininity to necessary and natural colonial status, insisting that the Jew, “like the woman, requires the rule of an exterior authority[”]. His formulation of femininity as racial inferiority lacks both Arnold’s sympathy with the inferior race, and his relative optimism about the causes and results of assimilation; the racial meaning of femininity had become less ambiguous, more decidedly damning. (p.24.) For further Irish literary associations with Nordau, see John Wilson Foster, ‘Against Nature? Science and Oscar Wilde’, in Between Shadows: Modern Irish Writing and Culture (Dublin: IAP 2009), under Wilde > Commentary [infra].

James Joyce - Ulysses: One of the crimes alleged against Leopold Bloom in the “Circe” episode of Ulysses is that he made a pass at a lady outside the house - presumably medical rooms - of Sir Thornley Stoker, the brother of Bram Stoker (not mentioned in the text). Mrs Yelverton Barry says in evidence: ‘Yes, I believe it is the same objectionable person. Because he closed my carriage door outside sir Thornley Stoker’s one sleety day during [591] the cold snap of February ninetythree when even the grid of the wastepipe and ballstop in my bath cistern were frozen.’ (Ulysses, Bodley Head Edn., 1965 &c., pp.591-92.)

Bad blood? The name of Dracula may derive from the Irish words droch fhola, meaning bad blood, according to Dr Mulvey-Roberts, senior lecturer at the University of the West of England, Bristol. (See Jamie Smyth, ‘Academic digs into Dracula’s Irish roots’, in The Irish Times, 5 Aug. 2004, reporting on the Bram Stoker Summer School.)

[ top ]

Liver salts? Stoker attributed the inspiration for his grim tale in Dracula to nightmare brought on by an injudicious supper of dressed crab that he had eaten. (See Patricia Craig, review of Paul Murray, From the Shadow of Dracula, in The Irish Times, 14 Aug. 2004, Weekend.)

Home-rule: Stoker styled himself a ‘philosophical Home-Ruler’ (Personal Reminiscences, 1906, Vol. 1, pp.26-31 [p.29]; Vol. 2, pp.343-44) - presumably meaning one who accepted Home Rule as more necessary than ideal.

Grand Old Man: Stoker sent a presentation copy of The Snake’s Pass (1890) to W. E. H. Gladstone, the Liberal premier, and was congratulated by him for making the case of ‘oppression by a “gombeen” man’.

Stage version: a stage-version of Dracula was produced by H. Dean and J. L. Balderston (NY Samuel French [1933]).

Film version (1): First of various film versions was the adaptations of the novel in F. W. Murnau’s silent-film Nosferatu (1922; var. 1921). A restored edition with colour tints was screened in Dublin IFC in 1997. Todd Browning made an early talkie-version as Dracula (1931). More than 200 films have been made on Stoker’s vampire theme. Christopher Lee’s impersonation in Dracula (1958) remains the classic version. Note that the title character in a film on the theme set chiefly in Louisiana and starring Brad Pitt (c.1990) describes the novel as ‘the vulgar fictions of a demented Irishman’.

|

| [See Dracula on Film -as attached.] |

[ top ]

Cross-roads (1): Oliver St. John Gogarty writes in I Follow St. Patrick (Rich & Cowan 1938): ‘God save all and sundry from their biographers, particularly to-day, when they wait till a man is dead and cannot defend himself, and then run a stake through his body at the cross roads in the form of a “Life” with all the envy and hostility of friends.’ (p.187.)

Cross roads (2): At the political ousting of Charles Haughey from government, Conor Cruise O’Brien wrote in the Observer: ‘If I saw Mr. Haughey buried at midnight at a crossroads, with a stake driven through his heart – politically speaking – I should continue to wear a clove of garlic round my neck, just in case.’ (Observer, 10 Oct. 1982.)

A. T. Q. Stewart, Edward Carson (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1981), comments that Stoker was son of a Dublin clerk who had won his way [to] the university and was renowned for his prowess as an athlete of ability. [6]

Famine fungus: ‘One man, a Church of Ireland Minister, the Reverend M. J. Berkley, correctly diagnosed the mould on the plants as a “vampire fungus”. Forty years later it was identified as Phytophthora infestans.’ (See Thomas Keneally, The Great Shame: A Story of the Irish in the Old World and the New, London: Chatto & Windus 1998, p.107.)

Murtagh Griffin was the middle-man (land-agent) who drew from Aogán O’Rahilly the malefaction of his most Rabelaisian verses: ‘For ever, O rude stone, bind down with zeal / The wandering rake by whom the country has been woefully despoiled ...]’, quoted in Benedict Kiely, ‘Land Without Stars; Aodhagan O’Rahilly’, in A Raid into Dark Corners and Other Essays (Cork UP 1999), pp.8-30, p.14.

Autograph letters: Catalogue of valuable printed books, autograph letters [of Walt Whitman] including the library of the late Bram Stoker, Esq. ... &c. (London: Dryden Press [for] Sotheby, Wilkinson & Hodge 1913).

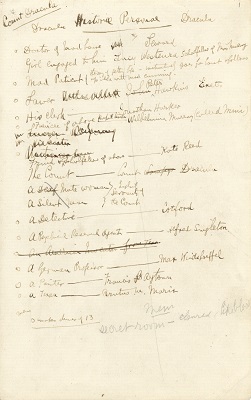

Notebooks: The original notes of Dracula (8 March 1890-17 March 1896, collected and mounted by Stoker’s literary executor before sale on behalf of Florence (Balcolme) Stoker at Sotheby’s, 7 July 1913; bought by a Mr Drake as item 182 [out of 317]; subsequently purchased from a Philadelphia dealer by the Rosenbach Museum and Library in Philadelphia on 25 Feb. 1970. (See Barbara Belford, Bram Stoker, 1996, p.261, ftn.) The collection includes a 9-page diary plotting the events of Dracula - as follows:

|

|||

| —Available at Swanriverpress blog - online [accessed 04.10.2017]. | |||

|

|||

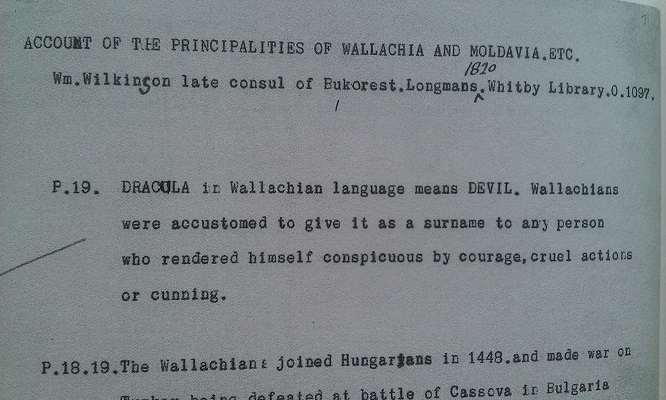

| See further - with illustrations and counter-remarks on the origins of the name “Dracula” and the date of its inclusion in the novel - as attached. | |||

[ top ]

Charlotte Stoker: the writer’s mother Charlotte was buried Mount Jerome Cemetery, 19 March 1901, in the grave of her son, Sir Wm Thornley Stoker. [Information supplied by Douglas Appleyard, 08-10-2012.]

Lucy Westenra: The unusual surname of Westenra pertains to a British officer in Sir Richard Musgrave’s account of the 1798 Rebellion in Memoirs of the Different Rebellions in Ireland (1801) - though no connection seems likely other than the token it supplies that the name was known to the Anglo-Irish community of the period:

‘Affifted by lieutenant-colonel Weftenra, and major Marley, they immediately advanced into the town, which was full of rebels, who were plundering and burning it; and who would have completely demolifhed [395] it, but that a few loyal fubjects, by keeping up a conftant fire from their houfes, retarded and checked their deftructive progrefs.’ (pp.394-95; available online.)

The Essay (BBC3): On 16 April 2012 Catherine Wynne gave a talk on Stoker for “The Essay” (BBC3) - the first of five contributions to the 15-min slot. - to be followed by Colm Tóibín in the second talk on the following day. The other speakers were Christopher Frayling, Roger Luckhurst, and Jarlath Killeen. (Go online; accessed 04.10.2017.)

Urn burial?: Stoker was cremated at Golders Green and his ashes placed in an urn in the East Columbarium there; his wife Florence’s ashes were scattered on her instructions in the Garden of Rest in front of the Ernest George Columbarium; Abraham Stoker, Snr., was bur. in the English Cemetery, Naples; See Ray Bateson, The End: An Illustrated Guide to the Graves of Irish Writers, Kilcock: Meath: Irish Graves Assoc. 2004).

Google Doodle: Google celebrated Stoker’s 165th birthday on 8 Nov. 2012 with a “doodle” citing Tag words listed were: Spider, Bat, Sage, Phonograph, Vampire, Moon, Birthday, Garlic, Castle. (See also Ben Bryant, “Bram Stoker celebrated by Google”, in The Telegraph (8 Nov. 2012) - online.

[ top ]