Life

| 1825-1901 [“Seabhach Siulach” (the Wandering Hawk); anglice “Mr Shooks”]; b. 26 Jan., Lilac Cottage, Blackmill St., Kilkenny; [adopted] son of John Stephens, a clerk to an auctioneer and book-seller; ed. briefly at St Kieran’s College, Kilkenny; trained as an engineer and worked on the Limerick and North Waterford Railway (then a-building); participated in Young Ireland rising of 1848 as aide-de-camp to William Smith O’Brien; wounded and reported killed at Ballingarry [to throw off govt. pursuit]; escaped to Paris; lodged at the boarding-house styled by Balzac ‘la maison Vauquer’; met John O’Mahony and Michael Doheny; lived by teaching English; acted as a ‘participant observer’ in Paris Commune, and the end of Second Republic absorbing the influence of French anarchism; remaining on on in Paris when O’Mahony went to America, 1853; returned to Ireland disguised as beggar with TC Luby [q.v.], 1856; undertook 3,000 mile walk though Ireland; taught French to children of John Blake Dillon; on foot (An ‘Seabhac Siubhalach; the Wandering Hawk’, or ‘Mr. Shook’), 1856-57; |

| received instructions from Emmet Monument Assoc. in America to organise for a revolution in Ireland; sent Joseph Denieffe with a reply outlining his requirements, and received assurances through Denieffe on his return along with the sum of £80 to fund the organisation; fnd. the Irish Revolutionary Brotherhood [afterwards known as Republican] on 17 March [St. Patrick’s Day] 1858, holding the inaugural meeting in premises of Peter Langan, a lathe-maker and timber-merchant at 16 Lombard Street, with Kickham, Thomas Clarke Luby, Peter Langan, Denieffe and Garrett O’Shaughnessy; organised the society on anarchist ‘cell’ principles, himself acted as ‘head centre’; orig. and later members swear oath ‘to make Ireland an independent Democratic Republic’; recruited wider membership through Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, John Devoy, William Roantree, and Patrick “Pagan” O’Leary; travelled to America, arriving at New York, 13 Oct. 1858 - first staying at Metropole Hotel; his ‘American Diary’, begun three months after his arrival there and kept up from 7 January 1859 to 25 March 1860, is held in the Public Records Office of Northern Ireland [PRONI; see infra]; |

| delivered candle-lit oration at grave of Terence Bellew McManus, 1861; fnd. The Irish People, staffed by Luby, O’Donovan Rossa, John O’Leary, and Charles Kickham, 1863; first number issued 28 Nov. 1863, with O’Leary brought from London to act as editor; Stephens contrib. his article “Felon-setting” to the 3rd and last edition; the paper raided and leaders arrested, 15 Sept. 1865; eluded the police until Nov. 1865, living as Mr. Herbert, a keen horticulturalist, at Fairfield House, Sandymount; arrested there with Kickham and Edward Duffy on the night of 11 Nov. 1865; repudiated British law at his arraignment (‘Now I deliberately and conscientiously repudiate British law in Ireland: I defy and despise any punishment it can inflict on me. I have spoken’); his escape from Richmond Prison organised by John Devoy within a fortnight, using funds supplied by Ellen O’Leary through the mortgage of her property and abetted by Irish warders Byrne and John J. Breslin (a medical orderly), 24 Nov., being due for trial on 27 Nov. 1865; |

| visited in Ireland by Thomas J. Kelly, who is sceptical of his claim to have recruited 85,000 mbrs.; postponed rising, Dec. 1865; accompanied Kelly to New York, 1866; denounced as ‘rogue, imposter and traitor’ by American Fenians and deposed as Head Centre, being succeeded by Kelly; disastrous rising of 1867 proceeds in Ireland without him, under Kelly’s command; retired to Paris; received subscriptions; expelled by French authorities; moved to Switzerland; contrib. recollections to The Irishman (2 Feb. 1882 onwards) and ‘Notes on a 3,000 miles walk through Ireland’ to Weekly Freeman (6 Oct. 1883 onwards); permitted to return to Ireland through intervention of Charles Stewart Parnell, 1885; lived in seclusion on Booterstown Ave., Blackrock; briefly appeared at 1798 centenary; d. 29 March [var. 2 April] 1901. DIB DIH FDA OCIL |

|

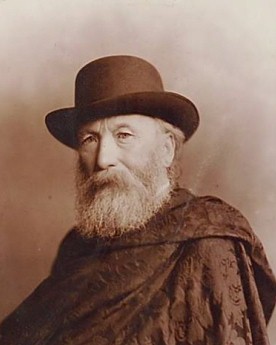

| James Stephens - Fenian ‘Head Centre’ |

Works

James Stephens, The Birth of the Fenian Movement: American Diary, Brooklyn 1859 [Classics of Irish History] (UCD Press 2009), 109pp. [vars. 144, 160pp]

[ top ]

Criticism| [ The entry in Dictionary of Irish Biography is by Marta Ramon (RIA 2009) - online. |

| Biographies |

|

| Fenianism (Select Reading) |

|

See also short account of Stephens’s escape from Richmond Gaol in M. J. MacManus, Adventures of an Irish Bookman, ed. Francis MacManus (Dublin: Talbot Press 1952), pp.24-28; Malcolm Brown, ‘Mr. Shook’, in The Politics of Irish Literature from Thomas Davis to W. B. Yeats (London: George Allen 1972) [Chap. 10], pp.151-63, and John O’Donovan, ‘The Irish Judiciary in the 18th- and 19th-Centuries’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4 (Winter 1971), pp.17-22, pp.17-18 [extract] |

See also Thomas Keneally, The Great Shame: A Story of the Irihs in the Old World and the New (Chatto & Windus 1998) - as per index: joins W. S. O’Brien in 1848 rising; at Ballingarry; wounded; meets Mitchel in USA; condemns O’Brien’s political aloofness; MacManus’s funeral; Us support for; James Kenealy meets; walking reconnaissance in Ireland; marriage; military preparations and training; in USA; Meehan’s loss of legal documents; instructs Kenealy; rescued from Richmond Prison; Fenians in the British Army; escapes in France; denounces Fenian raid on Canada; Mitchel’s resignation from Fenians; in Paris; Sexton requests amnesty for. |

See also Copy of the report of the inspectors general of prisons in Ireland to His Excellency the Lord Lieutenant with regard to the escape of James Stephens, British Parl., Accounts and Papers (1866), 147, LVIII: [36pp.; handwritten, plan, map; held at NL Scotland; Strathclyde UL, York ULibs.] |

[ top ]

Commentary

Isaac Butt: Butt wrote in ‘Land Tenure in Ireland: Plea for the Celtic Race’ (Dec. 1866), ‘The name of James Stephens is now familiar in every district of the great continent of North America - in every hamlet in the United Kingdom. It is known in every country in Europe. A few years ago he was an obscure individual - without wealth, or station, or distinction. If he is now formidable - surely he is so, even to British power - it is to be traced to nothing but this, that alone, unaided, without friends, or influence, or money, he dared to rely on the disaffection of Irishmen, wherever they were to be found, and with dauntless energy and an unwearying perseverance, set himself to appeal to it. If that disaffection had not existed in a character and with a fanaticism of which we can only form a faint idea from indications such as this, he would have only been beating the air.’ (The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing, gen. ed. Seamus Deane, 1991, Vol. 2 p.226). The passage continues with an estimate of the current strength of the ‘conspiracy’, which Butt puts at 5,000-10,000 men. (Ibid., p.227.)

See also George Sigerson, Modern Ireland (1868) on John O’Mahoney and James Stephens,

in ‘The Vitality of Fenianism’ [Chap.], quoted under O’Mahoney - as supra.

[Arthur Griffith,] Note on Stephens in Jail Journal, by John Mitchel [1854] (M. H. Gill 1913): ‘;Stephens was a railway engineer at the time of the outbreak in 1848, during which he acted as Smith O’Brien’s aide-de-camp. He received a bulletwound at Ballingarry, and was supposed to have been killed — obituary notices being published of him in the Kilkenny papers. He permitted the belief of his death to prevail as a cloak for a daring scheme to capture the British Prime Minister, and hold him as a hostage. The scheme miscarried, and Stephens reached France in disguise, where, with O’Mahony, he formed the design of the Fenian movement, and returning to Ireland travelled all through it survejdng the ground for the conspiracy. Dissensions arose in the Fenian movement after the end of the American Civil War, which Stephens calmed by promising insurrection in 1865 — at the time he was counting on England being embroiled in war over the Danish question. England, however, declined to go to war on behalf of Denmark, which had been led to believe she would do so, and Stephens postponed, the insurrection. His authority after this, dwindled ; and the Government struck a decisive blow at Fenianism by the arrest of its leaders in 1865. Stephens escaped, but his failure to redeem his promise to unfurl the banner of armed revolt in Ireland in 1866 caused his deposition and his formal denunciation as a traitor — which he certainly was not. He realised the impossibility of a successful insurrection in Ireland whilst England was not engaged in a war with one of the Great Powers, but he had built so far on such a war that he made extravagant promises which his followers believed, and which, when he was unable to redeem them, caused a large section to think he had deliberately played them false. After his fall Stephens removed to Paris where he lived in penury for many years. A few years before his death he returned to Ireland, and died at Blackrock, Co. Dublin.’ (p.449; available at Internet Archive - online.)

Frank Harris (My Life and Loves, 1922-27) - an account of his schoolboy reactions to Stephens: ‘I was thunderstruck and this amazement has always illuminated for me the abyss of Protestant bigotry, but I wouldn’t break with Howard, who was two years older than I and who taught me many things. One day I remember he showed me posted on the court house a notice offering £5,000 reward to anyone who would tell the where-abouts of James Stephens, the Fenian head-centre. “he’s travelling all over Ireland”, Howard whispered. “Everyone knows him”, adding with gusto, “but no one would give the head-centre a way to the dirty English.” I remember thrilling to the mystery and chivalry of the story. From that moment, head-centre was a sacred symbol to me as Howard.”’ (Life and Loves; 1964 Edn., p.18.)

[ top ]

Thomas F. Mahoney, in his review of Desmond Ryan, The Fenian Chief (1967) remarks that ‘A century after the zenith of the Fenian movement he principally launched, James Stephens is a relatively obscure figure.’ (p.140 in Mahoney, untitled review, Éire-Ireland, 4, 2, Summer 1969, pp.140-42.)

John O’Donovan, ‘The Irish Judiciary in the 18th- and 19th-Centuries’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4 (Winter 1971), pp.17-22; notes that James Stephens having evaded capture by police in 1848, went to Paris and went later to the U.S. as a professional agitator. (p.17) Notes that Robert Emmet was tracked and arrested by a fellow Dubliner who was an enthusiast for the Gaelic language and whose collection of Irish antiquities now rests in the National Museum. (p.18) Notes that Emmet’s barrister betrayed Emmet’s defence to the government prosecutor, as he had secrets of the United Irishmen.

Rolf & Magda Loeber, A Guide to Irish Fiction, 1650-1900 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006): ‘In Ireland, the development of the national tale with its emphasis on injustices inflicted upon the Catholic population, the adoption of the idea of Catholic Emancipation by Daniel O’Connell, and his translation of this idea into a mass movement, all somewhat fit [the] semination model [associated with Miroslav Hroch as applied to the Irish context by Joep Leerssen]. However, in the thicket of conflict, Irish revolutionaries had different ideas about the relationship between literature and social and political change. Some of them believed that that the real battle for nationhood was to be fought not on the cultural front, but was to be waged with land reform and Home Rule as the key pawns. For instance, James Stephens stated that a free Ireland would not be achieved by “amiable and enlightened young men … pushing about in drawing room society … creating an Irish national literature, schools of Irish art, and things of the sort”. He likened these idealists in 1863 to “dilettante patriots, perhaps the greatest fools of all ”. (Quoted in D. G. Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland, London 1982, p.177.) Michael Davitt’s Land League movement which operated from 1879 onward, also had little room for the literary ideals articulated by Thomas Davis in the 1840s and, instead, advanced the idea that control of land was essential for the Irish nation.’ (Also cites Seamus Deane, Short History of Irish Literature, London: Hutchinson 1986, p.76.)

[ top ]

Encyclopaedia Britannica (1949 Edn.), under ‘Fenians’, notes that the Fenian Brotherhood was est. by John O’Mahony, c.1858; oath allegiance to Irish republic ‘now virtually established’, swearing to take up arms and yield implicit obedience to leadership to officers; modelled on that of French Jacobins at the Revolution; ramifications in Canada, Australia, S. America, esp. US, and Irish population centres in Great Britain; not much hold on tenant-farmers or agricultural labourers in Ireland, and condemned by Catholic clergy; convention held by O’Mahony, Chicago, Nov. 1862; Stephens fnd. Irish People in Dublin, 1863; Government well served as usual by informers; Irish People suppressed, [15 Sept. 1865]; prominent Fenians sentenced; Stephens, through connivance of a prison warder, escaped to France; Habeas Corpus Act suspended [17 Feb. 1886]; considerable numbers arrested; Canada Raid under John O’Neill, 800 men crossing Niagara river; captured Fort Erie; large number of deserters; routed at Ridgeway by Canadian volunteers; surrendered to US Michigan, 3 June; second raid, 1870; betrayed by Henri Le Caron, ‘Inspector General of the Irish Republican Army’; unsuccessful insurrection in south and west Ireland, and Lancashire, 1867; Thomas J. Kelly and Capt. Deasy, prisoners, liberated by Fenians after trial in Manchester; death of police Sergeant Brett; Condon, Allen, Larkin, Maguire, and O’Brien arrested; Condon reprieved as American; Maguire pardoned, the others hanged; ‘Manchester Martyrs’; Clerkenwell explosion in order to liberate Richard Burke, kills 12 and maims 120; Michael Barrett apprehended and executed; Michael Davitt sentence to 15 years for part in Fenian Conspiracy; movement becomes practically obsolete, though Irish Republican Brotherhood and other organisations both in Ireland and abroad carried on the same tradition. (Note: dates in square brackets added from RIA Dictionary of Irish Biography, RIA 2009 - online.)

Roy Foster, Modern Ireland (London: Penguin 1988); civil engineer; joined Young Ireland, aide-de-camp to Smith O’Brien, 1848; fled to Paris; toured Ireland, 1856-57; convinced of feasibility of revolution; founded IRB, 1858; visited US to promote funds; blamed O’Mahoney for delay of revolution, 1861; On the Future of Ireland (1862); fnd. the Irish People, 1863; revisited US, 1864; stimulated funds by promising rising in 1865; fixed on anniversary of Emmet’s execution, 20 Sept.; offices of Irish People raided, 15 Sept. 1865; escape to Paris; rapturous greeting in NY on announcing plan to promote another rising; denounced for taking no action, 1867; returned to Paris; retired to Ireland, 1885, living at Blackrock in comfortable obscurity till death.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, selects ‘A Letter of Much Import, Written by James Stephens, in the Year 1861’, being Chap. XXII of Rossa’s Recollections 1838-1898 (1898); in the letter Stephen’s excoriates the theory of ‘a crisis’ summed up in the phrase ‘England’s difficulty is Ireland’s opportunity’, which he calls ‘a bane - a scourge - a disease - a devil’s scourge ... blind, base, and deplorable motto ... May it be accursed, it, its aiders and abettors. Owing to it the work that should never have stood still, has been taken up in feverish fits and starts, and always out of time, to fall into collapse when the ‘opportunity predestined to escape them’; the signature is ‘J. Kelly’ [263-61]; REFS & REMS, 207 [John Mitchel quarrelled with]; 209 [Mitchel and Lalor under leadership of Stephens organise to break connection with England by force, ed. S. Deane], 211 [Stephens, much criticised for deferral of revolution, at least recognised the scale of organisation necessary if farce-rebellions ... were to be avoided, Deane]; 226n [biog. note to Isaac Butt, as supra]; 227n [Stephens’s escape from Richmond prison organised by Devoy]; 243 [George Sigerson, as supra]; 250n [refers use of ‘England’s difficulty ... &c.’, in Kickham’s Knockagow to Stephen’s comment on same phrase, p.263 infra]; 252 [note to John O’Leary, Recollections of Fenians and Fenianism, establishing links between 1848 and the IRB movement]; 256 [O’Leary, Recollections, chap.VII, ‘... If Fenianism had been then, things might have been far different now; but the idea still lay more or less dormant in the brain of James Stephens, to wake up to activity, however, very soon after’]; 263 [‘Letter of Much Import ...’, as supra]; 266 [John Devoy, Recollections of an Irish Rebel, on ‘Burial of Terence Bellew McManus, ‘Stephens and Denieffe were the only Fenian leaders then in Dublin ... But some new men like the Sullivans of the Nation though it was their prerogative to take charge of all nationalist demonstrations, so when a committee was formed, there was a contest for control of it’], 268-74 [his escape from Richmond Prison in 1865]; 269-75 [Devoy, Recollections, Chap. XIII, on ‘The Rescue of Stephens’, ‘Stephens’ defiant speech when arraigned before the magistrate to be committed for trial led the public to believe that he had strong resources at his back. A week later most people felt that on the day of his arraignment he knew all about the arrangements for the rescue from prison, which afterwards took place on Nov. 24 1865, and that this knowledge justified his attitude of defiance ... Stephens at that time knew nothing of the possibility of escape ...’; a fully circumstantial account follows]; 300 [The Constitution of the IRB copied by Hobson, includes Art. 3 in which the organisation commits itself to awaiting the ‘decision of the Irish Nation as expressed by a majority of the Irish people as to the fit hour of inaugurating a war and England and shall, pending such an emergency, lend its support to every movement calculated to advance the cause of Irish independence, consistently with the preservation of its own integrity’]; 680 [Seumus Shields, in The Shadow of a Gunman, Act. 1: ‘... an’ when the Church refused to have anything to do with James Stephens, I tarred a prayer for the repose of his soul on the steps of the Pro-Cathedral’.]

COPAC lists Trials of the Fenian prisoners at Toronto who were captured at Fort Erie, C.W., in June, 1866, reported by George R. Gregg & E. P. Roden [CIHM/ICMH Microfiche series, 23495] ([Toronto] 1867), 3 microfiches [being the trials of Robert Blosse Lynch, John M’Mahon and David F. Lumsden are reported in full, the others briefly.]

ODNB: [Old] Dictionary of National Biography contains no entry for Stephens.

| Wikipedia: ‘1867 Rising’ (excerpt) |

|

|

| [...] |

| —Wikipedia - online; accessed 09.04.2024. |

[ top ]

Notes

Cabman’s shelter: There is an incidental reference to Stephens’s in the “Eumeus” episode of James Joyce’s Ulysses where Bloom and Stephen encounter the putative man ‘got away James Stephens’.

[ top ]