Life

| [bapt. John Francis Whelan; fam. Johnnie Whelan; later Sean O’Faolain; var. Seán; err. Ó Faoláin, since he did not use the accents in his publishing surname; occ. Seán Proinsias Ó Faoláin]; b. 22 Feb. 1900, 16 Half Moon [Halfmoon] St., Cork, third son of Denis Whelan, an RIC policeman and Bridget (née Murphy), first living above Nicholas O’Connor’s public house opp. stage-door of the Cork Opera House on Half Moon St., and later at No. 5 further up the street, away from the river; ed. Lancasterian National School, and later Presentation Brothers, 1913-18; much influenced by a teacher, Br. E. J. Connolly; sees Lennox Robinson’s Patriots on the Cork Opera House Stage and realises that his native city might also be ‘full of unsuspected drama’; takes part of Sean O’Falvey Daniel Corkery’s Clan Falvey performed by Grianan Players, 1917; enters UCC on a scholarship, 1918 (English, French and Latin); learns Irish at Gaelic League; takes holidays in West Cork Gaeltacht; meets Eileen [Ellen] Gould (d.1988), with whom Julia [q.v.] and Stephen); elected Auditor of Philosophical Soc.; taught by William Stockley, Chair of English (whom he castigates unfairly in Vive Moi); grad. English Language and Literature, 2nd Class Hons., Sept. 1921; MA in Irish, 2nd. Class Hons, 1924; MA in English, (Pass), 1925; | |

| becomes salesman in Irish language book firm; enlists in Cork No. I Brigade of IRA, and performs non-combatant duties chiefly as bomb-maker; serves as IRA Director of Publicity [propaganda] in Cork and later Dublin, editing a Republican news sheet with Molly Childers and P. J. Little, and answering to Erskine Childers, 1922-23; ed. An Long; re-enters UUC, Jan. 1924; wins Peel Memorial Prize and Ó Longáin Memorial Prize for a play, An Dán, in 1922; completes MA degree in Irish, 1924, with thesis on Daibhidh [Daithí] Ua Bruadair, partly published in Earna (1925); teaches in Christian Brothers school in Ennis, Co. Clare; contribs. to Irish Statesman, 1925-29; completes HDip. Ed., UCC; contribs. articles on education and Irish language to articles to Irish Tribune; leaves Ireland ‘with a strong smell of moral decay’ in his nostrils, to hold Harkness Commonwealth Fellow, Harvard University, 1926-28; his “Fugue” (‘my first successful story’), published in Hound and Horn, 1927; reviews Joyce’s Anna Livia Plurabelle for Criterion, 1928; receives John Harvard Fellowship, studying under F. N. Robinson and George Lynam Kittredge, 1928-29; grad. AM [MA] in comparative philology, Harvard 1928; | |

| teaches Anglo-Irish Literature at Boston College; m. Eileen Gould, June 1928 in Boston; she was later to suffering stress maladies on account of his philandering (called hypochondria by O’Faolain); ed. Lyrics and Satires of Thomas Moore (1929); teaches at Strawberry Hill College, England, 1929-33; befriended by Edward Garnett, the Jonathan Cape reader; applies for chair of English at UCC and supported by Alfred O’Rahilly but beaten by Daniel Corkery, 1931 - ‘a foolish affair ... democracy gone dotty’ (Vive Moi); issues Midsummer Night Madness (1932), first story-collection, introduced by Garnett, and promptly banned in Ireland; birth of dg. Julia, 1932; elected to Irish Academy of Letters, later in 1932; returns to Ireland on Garnett’s advice (‘green fields’), 1933, and settles in Killiney at “Knockaderry” - so-named by O’Faolain in memory of a childhood holiday place; birth of son; contribs. to Motley, ed. Mary Manning; contribs. to Ireland Today, 1936-38; issues A Nest of Simple Folk (1934), a novel, and Constance Markievicz (1934), a biography; with others, founded Irish PEN in 1934 to combat censorship; | |

| |

| issues a second novel, Bird Alone (1936), banned in Ireland; sends copy to James Joyce, who replies that he no longer reads novels and is unable to help; his play, She Had to Do Something (27 December 1937), based on wife of Prof. Stockley who establishes a ballet in Cork, is booed by first-night audience at the Abbey; issues A Purse of Coppers (1937), stories; introduced to Elizabeth Bowen (his “Irish Turgenev”) by Derek Verschoyle, (ed. Spectator), and commenced a love-affair at the Salzburg Festival, 1937, continuing till 1939 with trips to Bowenscourt; issues a revisionist life of Daniel O’Connell, King of the Beggars (1938), framing his signature argument that modern Ireland owes more to constitutional politics than to the physical-force movement; issues a study of De Valera (1939), for Penguin; issues Come Back to Erin (1940), a novel disparaging de Valera’s Ireland and the exilic illusions of ‘emigrants’; estabs. The Bell (1940), intended as a ‘blueprint’ for Irish society, acting as first editor; with Frank O’Connor, et al., contrib. to “Irish Issue” of Horizon; issues The Great O’Neill (1942), a revisionist look at the Elizabethan rebel which stands as ‘the record of an alternative culture’ (R. F. Foster, 1988); condemns Daniel Corkery as a false prophet in The Bell; issues ‘The Mart of Ideas’, in The Bell, 4 (June 1942) - on Irish censorship; | |

| [ top ] | |

| fnd.-mbr. Irish Civil Liberties, 1945; retires from editorship of The Bell, 1946, but contributes up to its cessation in 1954; consistently opposes power of Catholic hierarchy in Ireland, but reconverted to Catholicism in Italy, 1946; issues Teresa and Other Stories (1947); fnd. WAAMA (Writers, Actors, Artists and Musicians Assoc.); issues The Irish (1947), a ‘character study’ of his countrymen for Penguin, with prefatory remarks on the difficult of arriving at ‘any meanful synthesis’ of a history made of endurances rather than achievements [see note]; issues The Short Story (1948), based on critical essays and radio talks and characterising the form as quintessentially Irish - though overlooking the number of novels by Irish women authors such as Kate O’Brien, M. J. Farrell (Molly Keane) and Elizabeth Bowen; broadcast “Return to Cork”, 1948, offending local feelings; issues The Man Who Invented Sin (1948), stories; issues A Summer in Italy (1949); issues Newman’s Way (1952), a biography of Cardinal Newman; issues a further meditative travel work, South to Sicily (1953); writes The Promise of Barty O’Sullivan (1951), a Radio Éireann [RÉ] script for promotion of rural electrification; Cork Lord Mayor P. McGrath threatens resignation from chairmanship of Cork Festival committee if O’Faolain opens book exhibition, 1952; issues The Vanishing Hero, Studies in Novelists of the Twenties (1956), being lectures given at Christian Gauss Seminar in Criticism, Princeton University, 1953; | |

| appt. Director of Arts Council, 1957-59; issues The Finest Stories of Sean O’Faolain (1957); receives DLitt. [hon. causa], TCD, 4 July 1957; appt. Visiting Professor, Northwestern University, Illinois, 1958; awarded Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity, First Class, 1959; appt. Resident Fellow in Creative Writing, Princeton, 1959; Phi Beta Kappa Lecturer on several American campuses, 1961-62; issues I Remember! I Remember! (1961), stories; appt. writer-in-residence, Boston Coll., Spring of 1964 and 1965; issues Vive Moi! (1964), an autobiography embracing social and cultural analysis - but stripped of information about his many affairs which he later incorporated in the revised version edited by his daughter Eileen (1993); issues The Heat of the Sun (1966) and Stories and Tales (1966), story collections; appt. Resident at the Centre for Advanced Study, Wesleyan University, Connecticut, Spring 1966; refuses support for hon. degree of UCC, offered by Aloys Fleischmann on behalf of Alfred O’Rahilly, 1969, but later accepts it, being conferred with Micheal Mac Liammoir and Theo Moody, April 1978; issues The Talking Trees and Other Stories (1971); settles in Dun Laoghaire, 1972; publishes fiction very lucratively in Playboy in the 1970s; awarded hon. D.Litt., NUI; adjudicates Hennessy Awards with Kingsley Amis, 1973; issues Foreign Affairs (1975), stories; | |

| issues And Again (1979), a late novel in which Bob Younger lives his life backwards enjoying erotic adventures with is daughter, grand-dg., and great-gr.dg.; his Collected Stories were issued in two vols., 1980-82; suffered dementia following Eilean’s death, and was embroiled in a love-relation with a younger women; elected Saoi of Aosdána, 1989, agreeing to be nominated on second asking; d. 20 April 1991, in Dublin; bur. 4 May, Glasthule Church, memorial address delivered by Conor Cruise O’Brien accredits him with ‘Burkean magnanimity and generosity’ and links him with Hubert Butler and Owen Sheehy-Skeffington; his funeral being unattended by any representatives of Irish government while The Irish Times obituary comments: ‘If as a nation we have made any progress towards freeing ourselves spiritually, it was O Faoláin and a few like him who urged us on our way’ (22 April 1991); a memorial Mass was held two weeks later; estate at death valued at £301,915; there is an early oil portrait by Seán O’Sullivan, a late portrait of Edward Maguire and a head by Marjorie Fitzgibbon in the RDS; some of O’Faolain’s papers are in the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley; his letters to Professor Munira H. Mutran of São Paolo University (Brazil) were published in 2005. DIW DIH DIL KUN OCEL FDA OCIL | |

|

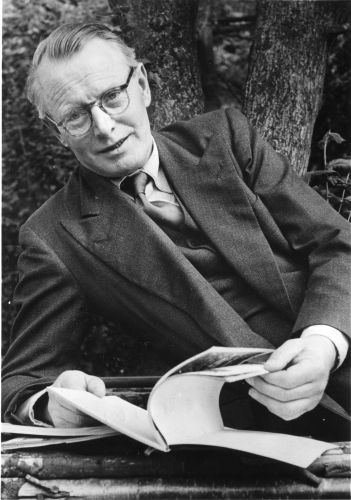

| Sean O’Faoláin |

| Works by O’Faoláin | Criticism on O’Faoláin |

| A comprehensive Primary and Secondary Bibliography of Sean O’Faoláin has been supplied by Marie Arndt [as infra]. Emendations to listings on the Works and Criticism pages of this dataset based of its contents are in progress. | |

Fiction

| Short stories collections |

|

For full listing of short-story titles in each collection, see “List of Works by Seán O’Faoláin”, supplied by Marie Arndt [as attached.] |

| Novels |

|

| [ top ] |

| Biography |

|

| Autobiography |

|

| Plays |

|

| Criticism |

|

| Travel |

|

| Correspondence |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

The Irish: A Character Study (West Drayton, Middlesex: Penguin 1947, [The Irish: A Character Study (West Drayton, Middlesex: Penguin 1947), 143pp. [with epigraph from Collingwood: ‘History proper is the history of thought. There are no mere events in history.’]; another edn. (NY: Devin-Adair 1948; rep. NY 1956, &c.), 180pp.; Do. [rev. edn.] (London: Pelican 1969), 173pp.; and Do., [rep. edn.] (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1980). [See extensive extracts, attached.]Consequences (Waltham St. Lawrence: Golden Cockerel Press 1932), [3] 66pp: ill., is a complete story in the manner of the old parlour game in nine chapters, each by a different author and contains ‘The man’ by John van Druten; ‘The woman’ by G. B. Stern; ‘Where they met’ by A. E.Coppard; ‘He said to her’, by Sean O’Faolain; ‘She said to him’ by Norah Hoult; ‘He gave her’ by Hamish Maclaren; ‘She gave him’ by Elizabeth Bowen; ‘The consequence’ by Ronald Fraser; ‘And the world said’ by Malachi Whitaker [Copy at Oxford]; O’Faolain, ‘Charles Dickens and W. M. Thackeray’ in Derek Verschoyle, ed., The English novelists: a survey of the novel by twenty contemporary novelists (London: Chatto & Windus 1936); Also published thesis in German, Ernst Haberlin, ‘Sean O’Faolain: die Erzahlungen (Zurich: Juris-Verlag, 1975). [COPAC/Oct. 1996]

[ top ]

| Selected Articles* |

|

*The foregoing list was contributed by Jason MacGeoghegan (MA Diss., UUC 1997). See also the full bibliography contributed by Marie Arndt [infra] which contains offprints listed in QUB Library Catalogue. Note also some inconsistencies in numeration of issues, supra.]. |

†Both cited in Gerry Smyth, Decolonisation and Criticism: The Construction of Irish Literature (London: Pluto Press 1998), References, p.247; also cites ‘John Millington Synge’ (1871-1909)’, in F. W. Bateson, ed., The Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, III (Cambridge UP [1967]), pp.1062-63. |

[ top ]

| A comprehensive Primary and Secondary Bibliography of Sean O’Faoláin has been supplied by Marie Arndt [as infra]. Emendations to listings on the Works and Criticism pages of this dataset based on its contents are in progress. | |

| Works by O’Faoláin | Criticism on O’Faoláin |

| Monographs | ||

|

||

| Articles, &c. | ||

|

||

| General studies | ||

|

||

|

||

| See also ... | ||

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Maurice Harmon, ed. Irish University Review: A Journal of Irish Studies, ‘Seán O’Faoláin Special Issue’, 6, 1 (Spring 1976), 139pp. CONTENTS: Maurice Harmon, Biographical Note [7]; Seán O’Faoláin, ‘A Portrait of the Artist as an Old Man’ [10]; Julian Moynahan, ‘God Smiles, the Priest Beams and the Novelist Groans’ [19]; Joseph Duffy, ‘A Broken World: The Finest Short Stories of Seán O’Faoláin [30]; Eilís Dillon, ‘Seán O’Faoláin and the Young Writer [37]; Vivian Mercier, ‘The Professionalism of Seán O’Faoláin’ [45]; Dermot Foley, ‘Monotonously Rings the Little Bell’ [54]; Eilean Ní Chuilleanain, ‘Dreaming in the Ksar es Souk Motel’ [63]; Hubert Butler, ‘The Bell: An Anglo-Irish View’ [66]; Donal McCartney, ‘Seán O’Faoláin: “A Nationalist Right Enough’ [73]; Hilary Jenkins, ‘Newman’s Way and O’Faoláin’s Way’ [87]; F. S. L. Lyons, ‘Seán O’Faoláin as Biographer’ [95]; Robie Macauley, ‘Seán O’Faoláin, Ireland’s Youngest Writer’ [110]. REVIEWS by Terence Brown, Michael P. Gallagher, Patrick Sheeran, Brian Cosgrove, Mairín Cassidy, Maurice Harmon, Art Cosgrove, Colin Owens, Jonathan Williams, Seamus Cashman, Colm McCarthy. [118] Books Received [138].

The Cork Review, ed. Sean Dunne, ‘Seán O Faoláin Special Number’, ed. (Cork: Triskel Arts Centre 1991). CONTENTS: Seán O Faoláin, ‘Interview with Brian Kennedy’, pp.4-6; Eilís Dillon, ‘Corkman and Writer’, pp.14-16; Eavan Boland, ‘That the Science of Cartography is Limited’ [poem]; Greg Delanty, ‘Letter from America’, pp.26-28, also ‘Aisling’ [poem], p.68; Maeve Saunders; Danny McCarthy; Robert O’Donoghue; Aloys Fleischmann, ‘Seán O Faoláin, A Personal Memoir’), pp.92-94; Conor Cruise O’Brien, ‘Memorial Address’ [delivered Glasthule Church, May 4]; Evelyn Conlon; Bryan MacMahon; Gerald Dawe; Gregory O’Donoghue; Brian P. Kennedy, ‘Interview with O Faoláin’; Leon O’Broin, ‘Just Like Yesterday’, [memoir of O Faoláin’s meeting with Frank Duff]; Dermot Keogh, ‘Democracy Gone Dotty’ [in the English chair at UCC]; W. J. McCormack, ‘O’Faoláin, Yeats and Burke’, pp.91; Dermot Healy; G. Y. Goldberg [Mayor of Cork]; John McGahern, ‘Why We’re Here’ [story]; Theo Dorgan; Julia O’Faoláin, ‘O’Faoláin at Eighty’ and ‘Post Mortem’, pp.7-13; the former printed in Fathers and Daughters, ed. Ursula Owen, Virago 1983]; Benedict Kiely, ‘Among the Masters’, pp.87-89; Thomas McCarthy, ‘Good Novembers’ [poem], p.52, also ‘Seán O Faoláin at the Diner Table’, p.57 [memoir of a meeting]; Val Mulkerns; Richard Murphy; Patrick Cotter; Maurice Harmon, ‘The Chair at UCC’; John Montague, ‘The Siege of Mullingar’, p.52 [poem], also ‘A Literary Gentleman’,pp.53-54; Jim Kemmy, ‘A Correspondence’; Gerry Murphy; Roz Cowman; Desmond Hogan, ‘Sean O Faoláin: A Journey’, [recalls first time out of Ireland, in Paris 1968]; J. J. Lee; Aonghus Collins; Seán MacMahon; Robert Greacen, ‘Sean O’Faoláin and The Bell’; Ronan Sheehan, ‘Reading O Faoláin’, pp.85-86; Kieran Burke; James Plunkett; C. J. F. McCarthy; Sean Dunne, ‘The Gougane Notebook’, p.97 [poem]; Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, ‘Dreaming in the Ksar Es Souk Motel: Poem, for Sean O Faoláin’, p.51; Fergus O’Ferrall, ‘Christian Sensibility and Intelligence: The Witness of Seán O Faoláin’, pp.79-84; quoting extensively from Vive Moi, A Summer in Italy, and Newman’s Way, with ftns.]. Includes ‘Prendergast’, a story in Irish by Sean O’Faoláin reprinted from Éarna, 2, 5 (June 1924); Cork Review, pp.20-21; and ‘The Woman Who Married Clark Gable’, another story, pp.70-72; also contains Mary Lavin, ‘The New Gardener’, pp.60-62 [the story that O’Faoláin liked best]. For Selection, see infra.

Munira H. Mutran, “A Personagem nos Comes de Sean O’Faolain.” PhD Thesis. 1977. Advisor: Paulo Vizioli. Starting from O’Faolain’s statement that his main literary merits are to be found in the short fiction, the study of seventy six of his stories reveals that their main focus of interest is character. If character is so significant in O’Faolain’s stories, two questions arise: how is it revealed, and how is it related to the other narrative elements? The first part of the study deals with the basic techniques in character building such as physical descriptions, behaviour, discourse, and point of view. The second part examines character in relation to its surroundings, time, and theme. Although not immune to the influence of historical time in his first collections, O’Faolain, while still concerned with the social context, shows in his other works an increasing interest in the individual in a moment of self-awareness, or of discovery of the mysteries of life. His typical and recurring creation is a lonely, sad/ funny middle-aged or old man (or woman) tormented by memories and by the impossibility to re-live the past, presented in an ironic or satirical tone. (See in Irish Studies in Brazil [Pesquisa e Crítica, 1], ed. Munira H. Mutran & Laura P. Z. Izarra (Associação Editorial Humanitas 2005) - MA Dissertations and PhD Theses of USP 1980-2005, p.297.

Marie Arndt, review of Sean O’Faolain’s Letters to Brazil, ed. Munira H. Mutran (2005), in ibid., p.315-38: ‘I do believe that the relationship Munira Mutran established with O’Faolain made her overlook the ambivalence in the man. This is evident as she claims that, “On Ireland, and the world, and about the Irish... he [O’Faolain] is, as always, earnestly objective”. This statement is missing the point of why O’Faolain’s writing is so interesting to investigate; he was never objective, but very often ambivalent about his fellow countrymen and his native county, and the grass was almost always greener on the other side of the fence, that is, out of Ireland. But when he was away from home - always the inspiration in his writing - he missed it badly. His relationship to Ireland was “An Inside Outside Complex”, to echo the tide of one of his short stories, never feeling comfortable inside, but not wanting to be left on the outside.’;

[ top ]

Commentary

See separate file [infra].

Quotations

See separate file [infra].

References

Desmond Clarke, Ireland in Fiction: A Guide to Irish Novels, Tales, Romances and Folklore [Pt. 2] (Cork: Royal Carbery 1985), lists Midsummer Night Madness and Other Stories (London: Jonathan Cape 1932), 284pp. [stories on aspects of Anglo-Irish and Civil Wars]; A Nest of Simple Folk (London: Jonathan Cape 1933), 296pp. [family life 1854-1916, and career of Leo Foxe-Donnell scion of two families of different social standing, a libertine and a rebel, imprisoned for fifteen years in Dartmoor and Portland Prisons, and later Maryborough Gaol [Portlaoise], as a Fenian, a close study of peasant life]; Bird Alone (London: Jonathan Cape 1935), 304pp. [the tragedy of Cornelius Crone, who ‘set his mouth against God’, and his grandson Corney, in love with Elsie Sherlock, who dies tragically; set in the Parnell crisis of 1890s]; The Born Genius (Detroit: Schuman 1936), short story rep. [in] seq.; A Purse of Coppers, stories (Cape 1937), 286pp.; Come Back to Erin (London: Jonathan Cape 1940), 350pp. [Frankie Hannafay, on the run, smuggled to New York, tries in vain to interest American-Irish in his plots, immoral character, returns to Ireland]; Teresa and Other Stories (London: Jonathan Cape 1947), 160pp. [a old nun’s pilgrimage to Lisieux, gently satirical]; The Man Who Invented Sin (NY: Devin-Adair 1949), 160pp., being the America edn. of St Teresa &c; The Stories of Seán O’Faoláin (London: Rupert Hart Davies 1958), 385pp. [27 stories, 20 appearing for the first time in English publication, reviewed as follows, ‘he writes with tongue in cheek of [Ireland’s] listlessness and apathy towards the arts, her fleshy priests and the shortcomings of her predominantly Roman Catholic religion, the latter beautifully expressed and redeemed in his final story.’]

| Who’s Who: O’Faoláin’s autograph entry in Who’s Who gives his hobby as ‘daydreaming’. |

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2; selects “Midsummer Night Madness”. REMS & REFS: O’Faoláin held that it was Connolly who introduced the idea of the continuous Irish nation, but mistaken [ed. Luke Gibbons, 953]; vengeful flames in big house fiction [Augustine Martin, ed.; 1022]; The Hounds of Banba sets the tone for Corkery’s Cork disciples, O’Faoláin and O’Connor, as well as O’Flaherty [Martin, ed.; 1023]; looking back on the war of Independence with mixed emotions [Martin, ed., 1024]; Catholic clergy, focus of satire in the Bell and other lit. mags. [Martin, ed.; 1026]; [cf. Liam O’Flaherty’s ‘Mountainy Tavern’ and O’Faoláin’s ‘Guests of the Nation’ [Martin, ed.; 1144]. FDA3 selects The Bell, editorial (June 1943), “The Stuffed-Shirts” [FDA3 101-07; see Quotations, supra]; from A Purse of Coppers, ‘A Broken World’ [107-12]; Vive Moi!; ‘The Gaelic Cult’ [569-73, ‘… the Gaelic Nation as a political theory has no pedigree … all the poor devils could think of was the return of the Stuarts, and, presumably, some kind of Anglo-Irish monarchy to patronise poetry’, 570-71], an essay explicitly directed against Corkery, and excoriating the Revival movement as a form of jobbery. Further REFS & REMS, the Bell produced a body of biting, pungent, commonsensical, clearly argued realistic analyses … the censorship of books particularly drew [his] wrath, the Gaelic revival was excoriated as mere jobbery, the romantic image of Irish peasant … denounced as a denial of social reality in rural Ireland … [his] primary theme that Ireland was not a great, restored nation but a country at the beginning of its creative history, and at the end of its revolutionary history [&c. ed. Terence Brown], 91-92, 93] [glancing allusion in Beckett, ‘Recent Irish Poetry’ (1944), 247]; the writer’s struggle to ‘universalise the data I had experienced in my body locally’, as Seán O’Faoláin puts it in Vive Moi! [ed. Seamus Deane], 382; Frank O’Connor, An Only Child, ‘Corkery’s greatest friend was Seán O’Faoláin, who was three years older than I and all the things I should have wished to be - handsome, brilliant, and above all, industrious. For Corkery, who loved application, kept rubbing it in that I didn’t work as O’Faoláin did [narrates an encounter where Corkery makes him jealous speaking admiringly of O’Faoláin, “There goes a literary man”], 473-74; [O’Faoláin’s central position in the challenge to Catholic triumphalism in Ireland; note that he exempted Seán Lemass for his strictures; O’Faoláin sees demise of Gaelic Ireland as having less to do with colonialism than its own incapacity for adaptation, [ed. Luke Gibbons] 561-568, passim; [ed. J. W. Foster; note O’Faoláin’s pronouncement on Irish realism, ‘The whole social picture is upside down and we do not know where we are or what is real or unreal’; the Irish writer must turn inward ‘for there alone in his own dark cave of self can he hope to find certainty or reality’, 937-43; [biog. Julia O’Faoláin, 1134]; [Gabriel Fallon compared with, ed. Declan Kiberd, 1310]; [ibid., 1312]; John Montague, in “The Siege ofMullingar”: ‘Puritan Ireland’s dead and gone, / A myth of O’Connor and O’Faoláin’, 1353-54. BIOG, 127 [see supra]. See also Luke Gibbon’s remarks: ‘O’Faolain argued that the demise of the ‘Hidden Ireland” had less to do with colonial oppression than with its own incapacity, as an anachronistic social order, to face up to the advent of democracy and modernisation.’ (FDA 3; p.562). FDA omits reference to Come Back to Erin (NY: Viking 1940). Note, editorial essays in The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing(1991), Vol. 3, making significant allusion to Seán O’Faoláin incl. Terence Brown, ‘The Counter Revival: Provincialism and Censorship 1930-65’ [FDA Vol. 3], pp.89-93; Luke Gibbons, ‘Challenging the Canon: Revisionism and Cultural Criticism’ [ibid.], pp.561-67, and Gibbons, Constructing the Canon: Versions of National Identity’ [ibid.] q.pp.

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama (1987) lists RTÉ films of Lovers of the Lake, adapt. by Alun Owen and dir. by Tony Barry in Love Stories of Ireland ser. (1984); film of the story (in Coll. Stories, Vol. 3), The Woman Who Loved Clark Gable, with Bob Hoskins and Brenda Fricker [q.d.]

Catalogues: Hibernia Catalogue (No. 19) lists ‘Irish Poetry since the War’, in London Mercury (1935); ‘South Riding’, in London Mercury (1936); Belfast Public Library holds 15 titles up to 1958.

[ top ]

| Sense of place?: O’Faolain calls Cork ‘a sewer’ in A Purse of Coppers. |

“Lovers of the Lake” concerns Bobby and his mistress Jenny. At a crisis in their relationship, she goes to Lough Derg, and he follows. She does not find the solution to the conflict of conscience and desire, but he - an atheist - is strangely moved. There is also a sense of harmony established between male rational secularism and female impulsive piety. And finally, there is an interrogation of conventional selfhood, ‘[I]nside ourselves we have no room without a secret door; no solid self that has not a ghost inside it trying to escape.’ (Selected Stories, London 1978, p.46; cited n Peter Barr, ‘Litanies of Doubt - The Literature of Lough Derg: William Carleton, Patrick Kavanagh, Denis Devlin, and Seamus Heaney’, MA thesis, UUC 1994.) Note that the story is said to be based on the legend of ‘Curithir and Liadain’ acc. to Benedict Kiely (‘An Image of the Irish Writer’, in Raid into Dark Corners, 1999, p.147.)

The Bell: A Magazine for Creative Fiction (1940), and so subtitled throughout its first run, ceasing in April 1948; named after the Russian emigré magazine Kolokoli [i.e., ‘Bell’], with financial support from Joseph McGrath; first issue, ‘A Survey of Irish Life’, with contribs. from Elizabeth Bowen, Flann O’Brien, Jack B. Yeats, Lennox Robinson; dedicated in first editorial to ‘Life before any Abstraction’; resumed by Peadar O’Donnell in Nov. 1950.

Sales pitch: Mary Kenny remarks that The Bell sold 3,000 copies a month while the Irish Messenger of the Sacred Heart sold 300,000, and that Sean O’Faolain came to the support of the Allies in the war - a policy opposed by the other journal. (See Peter Somerville-Large, ed., Irish Voices: An Informal History 1916-1966, Pimlico 2000, as reviewed in Times Literary Supplement, 8 Sept. 2000.)

Quo vadis? OFaolain decided with Eileen that they ‘could only live in Europe, and in Ireland’, while travelling in New Mexico where the landscape, though spectacularly beautiful, struck them as devoid of meaning (Vive Moi); MA in English at Harvard, 1929; much influenced by Henry James’s essay of the life of Nathaniel Hawthorne and the problems of the writer in a young society lacking ‘the complex social machinery [necessary] to set a writer in motion’, the ‘complexity of manners and types’, and the ‘accumulation of history and custom’ (Vive Moi, 241f).

Daniel O’Connell: O’Faoláin believed him to ‘practical, utilitarian, unsentimental’, and thus ‘a far more appropriate model for twentieth century Ireland, than any figure drawn from the sagas or the mists of Celtic antiquity’. Further, ‘Benthamite, English-speaking and philosophical about the loss of Gaelic [he was] a figure to inspire a new Ireland.’ (Quoted in Terence Brown, in Ireland, A Social and Cultural History 1922-1985, London 1987, pp.156-57.)

Ex cathedra: O’Faolain applied for the Chair of English at Cork University, and was surprised to be beaten by his former mentor Daniel Corkery, who had no primary degree. In latter life he was depressed by fears that he had wasted his life; his women included Eileen O’Faolain, Elizabeth Bowen; Honor Tracy; and Alene Erlanger, the New York hostess; in old age he made a fool of himself with younger women. Note that the Anglo-Irish character in his story ‘Midsummer Night Madness’ who loses all except his love for a gipsy is called Henn [cf. T. R. Henn].

Gerald Dawe: Dawe cites an article by O’Faolain at the time of the Long Kesh Hunger Strike (The London Review of Books, Oct. 1981), in which O’Faolain reflects that the hunger-strikers were part of an Irish belief in sacrifice, and that sacrifice is seen not as a denial of political possibility, but as its consummation in The Hero. (Dawe, ‘Living in Our Time’, in Linen Hall Review, Summer 1990, p.42.

Sean & Honor: Candid Extract from the supplement to Vive Moi (1993) dealing with O’Faolain’s sexual relationship with Honor Tracy appeared in Sunday Independent, 12 Nov. 1993, under the banner ‘Honor and Glory’, pp.1, 6.

Ulick O’Connor recalls that O’Faolain expressed a strong dislike for the works of Beckett and Flann O’Brien and makes a list of one-poem-poets incl. Maurice Craig with his ballad of Belfast. (Kevin Kiely, review of O’Connor, Diaries 1970-1981: A Cavalier Irishman, in Books Ireland, Nov. 2002, p.281.)

Colin Graham writes of The Irish: Even Sean O’Faolain’s attempt, in The Irish, to undo histories which are ‘nationalist, patriotic, political, sentimental’, describes its method as telling ‘the story of the development of a national civilisation’; and ends with a wry, but essentially unadulterated, utopian vision: ‘How beautiful, as Chekhov would say of his Russia, life in Ireland will be in two hundred years time.’ (pp.9 & 169; in Graham, Deconstructing Ireland: Identity, Theory and Culture, Edinburgh UP 2001, p2.)

[ top ]