Constance Markievicz [Countess]

|

|

| Life | |

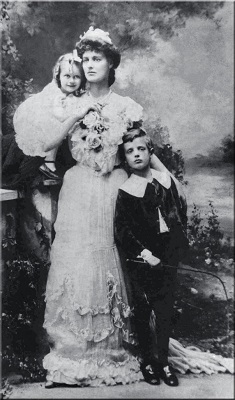

1868-1927 [née Constance Georgina Gore-Booth], b. 4 Feb. 7, Buckingham Gate, London, eldest daughter of Sir Henry Gore-Booth, of Lissadell, Co. Sligo, and Georgina Hill Gore-Booth, orig. from Tickhill Castle, Yorkshire, and dg. of Lord Scarborough; s. of Eva Gore-Booth; ed. at home in Lissadell [built 1832], and the Slade in London, and in Paris; met Casimir Dunin, Count de Markievicz of Staro Zyvotov, Poland, whom she married in 1900 after his wife’s death the previous year; their only child, Maeve Alys, b. 1901, at Lissadell; joined Gaelic League; appeared in George Russell’s Deirdre (1902); |

|

fnd. United Arts Club with Casimir and Ellen Duncan, 1907; espoused nationalism having read issues of Peasant and Sinn Féin in cottage at Ballally previously rented by Padraic Colum; member of Inghinidhe na hÉireann with Maud Gonne; fnd. Fianna Éireann, Republican youth-movement, in response to 800-strong rally of Boys Scouts, advertising a meeting for boys ‘willing to work for the independence of Ireland’, 1909; feminist campaigner; ran soup-kitchen in 1913 Lock-Out Strike; departure of Casimir for Ukraine; |

|

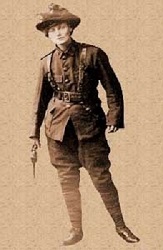

served at Royal College of Surgeons, Easter Rising 1916, as second-in-command to Michael Mallin; condemned to death for part in Easter Rising, as an officer in James Connolly’s Citizens Army, acting as deputy leader of unit holding College of Surgeons (where she is reputed to have shot a DMP-man at close range with her revolver “Peter the Great”); refused offer of transport from Capt. de Courcy Wheeler (‘No, I shall march at the head of my men ... I shall share their fate’); afterwards reprieved on account of her gender - acc. Gen. Maxwell &#q45;solely on account of her sex’ - and objected violently to the measure; imprisoned in Aylesbury Gaol and later Holloway (London) and Cork Jail; released under general amnesty, 1917; |

|

converted to Catholicism two weeks after release, influenced by the bearing of Michael Mallin before his execution; made Freeman of Sligo, Aug. 1917; elected MP for St Patrick’s division, Dublin, 1918, and thereby became the first woman MP elected to Westminster though she did not take her seat, being in Holloway Gaol at the time; joined Dáil Éireann (22 Jan. 1919); appt. first Minister of Labour in Dáil Éireann; supported the Republican side in the Civil War; toured America as Republicans fund-raiser; published 2 poems in Catholic Bulletin, 1921-22; visited Jim Larkin in Sing Sing Prison, 1922; |

|

defeated in general election, 1922; elected TD, Dublin Borough South, Aug. 1923; arrested as Republican, Nov. 1923; hunger strike; joined Fianna Fail in 1926, adopting constitutional politics; re-elected, 1927; d. from peritonitis in public ward of St Patrick Dun’s Hospital, 15 July, 1927, attended by Casimir; bur. Glasnevin, with reputed funeral procession of 300,000, and a eulogy by Eamon de Valera, while Kevin O’Higgins was being buried at the same hour; her Prison Letters were edited by Ester Roper (Prison Letters, 1934); a bibliography was prepared by P. S. O’Hegarty in 1934; there is a romantic portrait by her husband in the National Gallery of Ireland; Jeremy Corbyn announces Markievicz memorial at Islington, Sept. 2015. DIB DIH OCIL |

|

| [ top ] |

| Advise to lady insurgents .. |

| “Dress suitably in short skirts and strong boots, leave your jewels in the bank and buy a revolver.” |

| A pledge .. |

| “I am pledged to a free independent Republic .. a workers’ republic.” |

Works

Esther Roper, ed., Prison Letters of Countess Markievicz, preface by President De Valera [also poems and articles relating to Easter week by Eva Gore-Booth, and a biographical sketch by Esther Roper] (London: Longmans, Green 1934), rep. with an introduction by A. Sebestyn (London: Virago Press 1986); another edn. ed. Lindie Naughton (Dublin: IAP 2018), 277pp.

[ top ]

Criticism| Full-length studies |

|

| Various studies |

|

See also Margaret Ward, ‘“The Suffrage Above All Else!”: An Account of the Irish Suffrage Movement”, Irish Women’s Studies: A Reader, ed. Ailbhe Smyth (Dublin: Attic Press 1993), given under John Redmond [infra]; Joanne Mooney Eichacker, Irish Republican Women in America: Lecture Tours, 1916-1925 (Dublin: IAP 2003), 352pp. [incls. rems. on Constance Markievicz, et al.]; Dermot James, The Gore-Booths of Lissadell (Woodfield Press 2004), 400pp.; Gerard Moran, Sir Robert Gore Booth and His Landed Estate in County Sligo, 1814-1876 (Dublin: Four Courts Press 2006), 64pp.; and query Margaretta D’Arcy, Prison Voice of Con Markievicz [n.d.]. |

[ top ]

Commentary

W. B. Yeats, “Easter 1916”: ‘That woman’s days were spent / In ignorant good-will, / Her nights in argument / Until her voice grew shrill’ - lines drafted as: ‘... ignorant good will; / All that she got she spent, / Her charity had no bounds.’ (Quoted in Frank Tuohy, Yeats, 1976, p.163).

W. B. Yeats, “On a Political Prisoner” [‘... Recall the years before her mind / Became a bitter, an abstract thing’], and ‘In Memory of Eva Gore-Booth and Countess Markievicz’ [‘The light of evening, Lissadell, / Great windows, open to the south, / Two girls in silk kimonos, both / Beautiful, one a gazelle’; also, ‘The innocent and the beautiful / Have no enemy but time ... .’]

Sean O’Casey [as P. Ó Cathasaigh], The Story of the Irish Citizen Army (Maunsel 1919), “Seeing that Madame Markievicz was, through Cumann na nBan, attached to the Volunteers, and on intimate terms with many of the Volunteer leaders ... inimical to the first interests of Labour, it could not be expected that Madame could retain the confidence of the Council; and that she should now be asked to sever her connection with either the Volunteers or the Irish Citizen Army.” (O’Casey motion as Hon. Sec.) [45] A vote of confidence in Madame Markievicz, with ensuing apologies, passed seven to six. O’Casey refused to withdraw his comments, ‘he was sorry he could not do as Jim suggested, and that that his decision was definite and final.’ [46] O’Casey replaced as Secretary by J. Connolly, and afterwards Sean Shelly, Michael Mallon, W. Halpin, and M. Nolan included on Executive. [47]

[ top ]

Eva Gore-Booth [q.v.]| “To C. M. on Her Prison Birthday” | |

| February 1917 | |

| What has time to do with thee, Who host found the victor’s way To be rich in poverty, Without sunshine to be gay, To be free in a prison cell? Nay on that undreamed judgment day, When on the old world’s soap-heap flung, Powers and empires pass away, Radiant and unconquerable Thou shalt be young. |

|

| “Comrades” — To Con. | |

| The peaceful night that round me flows, Breaks through your iron prison doors, Free through the world your spirit goes, Forbidden hands are clasping yours. The wind is our confederate, The night has left her doors ajar, We meet beyond earth’s barred gate, Where all the world’s wild rebels are. |

|

|

|

[ top ]

Liam O’Flaherty (The Martyr, 1933), contains a composition portrait of Countess Markievicz and Maud Gonne: ‘It was no other than the famous Angela Fitzgibbon who stood before him. The daughter of a wealthy landowner called Colonel Fitzgibbon, she had created a scandal by taking part in the rebellion of 1916, being captured in a volunteer’s uniform with a smoking revolver in her hand, her tunic bloody from a wound in her side. Since then she had become an legendary figure in Irish political life. An outcast from her own class, she was regarded by the revolutionary mas of the [234] people as a living symbol of their insurrection. To them she was the fairy queen of whom the poets had sung, the Dark Rosaleen who was the spirit of the enslaved motherland, now walking the earth to urge on the risen warriors to victory. / Yet victory never seemed to follow in the tracks of this dark angel. Instead, she seemed to be the harbinger of death. Up and down the land she went, enslaving by her beauty whatever leaders she imagined for the moment to be pregnant with the nation’s destiny. And death came to whomesoever she influenced.’ (pp.62-63; quoted in Patrick Sheeran, The Novels of Liam O’Flaherty, Wolfhound 1976, pp.254-55; note that Sheeran directly quotes the lines of Yeats, ‘Two girls in kiminos ...’, normally associated with the Gore-Booths of Lissadell.

Maurice Headlam, Irish Reminiscences (1947): I suppose that most of the members were of more or less strong Nationalist sympathies, such as Yeats, and indeed many others. But those sympathies were not obtruded as a rule: but I have recollections of the famous (or infamous) Countess Markievicz striding up and down the room describing how “Jim” meaning the Labour leader, Larkin - of the great Dublin strike was defeating the employers. She was a Gore-Booth of a landlord family in Sligo, who went to Paris as an art student and married a Polish Count whom she brought to Dublin - a heavy uninteresting man who also had been an art student. She afterwards became a Sinn Féin leader (as well as the first woman to be elected to Parliament as a member for an Irish, or, I believe, any other constituency, though she never took her seat); and she was reported to have shot a policeman in the back with revolver from a window in Stephen’s Green during the Rebellion. She was, I believe, tried and condemned to death, but reprieved. When I knew her she had lost the looks Yeats as a young man had so much admired, and was a haggard witchlike creature.’ (p.48).

[ top ]

Cheryl Herr, For the Land They Loved, Syracuse UP 1991), comments, ‘Constance Gore Booth, Countess Markiewicz who not only acted at the Abbey but also joined the Irish Citizen Army, supported the labour movement, epitomised one style of Irish feminism, and took part in the Easter Rising.’ (p.57).

C. L. Innes, ‘“A Voice in Directing the Affairs of Ireland”, L’Irlande libre, The Shan Van Vocht, and Bean na h-Eireann’, in Paul Hyland and Neil Sammells, eds., Irish Writing, Subversion and Exile (Macmillan 1991), pp.146-58, Bean na hEireann was founded at a meeting called by Helena Moloney, at which were present Con Markievicz, Ella Young, and Sydney Gifford, standing for ‘The Freedom of Our Nation and the complete removal of all disabilities of our sex’; an article signed ‘Maca’ [pseud. Countess Markievicz] calls for ‘Free Women and a Free Nation’, arguing that ‘no one should place sex before nationality or nationality before sex’; ‘We will teach our men to look upon us as fellow-Irelanders and fellow-workers, willing to strive as they have striven, to die as they have died, of whose usefulness there can be no question, and on whose right to citizenship no doubt can be thrown’. Also, Countess Markievicz wrote in her gardening column in Bean na hEireann: ‘A good nationalist should look upon slugs in a garden much in the same way as she looks upon the English in Ireland, and only regret that she cannot crush the Nation’s enemies as she can the garden’s, with one treat of her dainty foot.’ (Cited in C. L. Innes, Women and Nation in Irish Literature, Wheatsheaf 1993, quoting from E. Ní Eireamhoin, Two Great Irishwomen (Dublin: Fallon 1971); also in Innes, ‘“A Voice [... &c.]”’, in Hyland & Sammells (1991), p.157.)

Emma Donoghue, Hood (Penguin 1997), incls. a reference to Markievicz when the main character Pen [Penelope] is walking across St. Stephen’s Green in the 1990s: ‘I nodded to Con Markievicz as I passed; her bronze head was almost hidden in holly and purple leaves. I had always loved the story of her setting her citizen army to dig trenches here in 1916 without thinking how easily they would be gunned down from the windows of the hotels that overlooked the Green. Or no, maybe I was underestimating her. Maybe she knew what would happen, but wanted to keep her men busy, like the games I made up for my Immac [i.e., Immaculate School] girls on sleepy afternoons.’ (p.184.)

Kevin Myers, Watching the Door: A Memoir 1971-1978 (Dublin: Lilliput Press 2006): ‘The vilest murders in the past [i.e., before the Northern Irish Troubles] had been blessed with a retrospective absolution. Countess Markievicz, the revolutionary - her name came from the unfortunate Polish husband, who soon fled her neurotic badness for the serenity of war on the eastern front - murdered an unarmed and helpless police officer, a working-class Irishman named Constable Lahiffe, in St Stephen’s Green during the Easter Rising in Dublin in 1916. There is now a statue to her there - but as for poor Lahiffe, he is simply forgotten.’ (p.63.)

[ top ]

Quotations

Suffrage soc.: ‘I would ask every nationalist woman to pause before she joined a suffrage society or franchise league that did not include in their programme the freedom of their nation. A free Ireland with no sex disabilities in her constitution should be the motto of all nationalist women.’ (In Margaret Ward, ed., In Their Own Voice: Women and Irish Nationalism, Attic Press 1995, q.p.; quoted in Marie Duffy, UU Diss., UUC 2007.

3 movements (The Irish Citizen [q.d.]): ‘[T]hree great movements were going on in Ireland in those years, the national movement, the women’s movement, and the industrial one.’ (Quoted in Margaret MacCurtain, ‘Women, the Vote and Revolution’, in MacCurtain & Donnacha O Corrain, eds., Women in Irish Society: The Historical Dimension, Conn: Greenwood Press 1979, pp.52, 53; both quoted in Carol Shloss, ‘Molly’s Resistance to the Union: Marriage and Colonialism in Dublin, 1904’, in Molly Blooms: A Polylogue on “Penelope” and Cultural Studies, ed. Richard Pearce, Wisconsin UP 1994, p.117 [note 2].)

Full rights: ‘Fix your minds on the ideal of Ireland free, with her women enjoying the full rights of citizenship in their own nation.’ (Quoted in MacCurtain, op. cit. 1979, p.53; cited in Carol Shloss, op. cit. 1994, idem.)

[ top ]

References

Henry Boylan, A Dictionary of Irish Biography [rev. edn.] (Gill & Macmillan 1988), ‘In 1906 she rented a cottage in Ballally in the Dublin Mts. and came across back numbers of The Peasant and Sinn Féin, left by the previous tenant, Padraic Colum [thus] her interest in her country’s struggle for freedom was first aroused.’ Note that the anecdote of her discovering copies of Ryan’s Irish Peasant and Griffith’s Sinn Féin in Colum’s vacated Irish cottage is narrated more substantially in Leon Ó Bróin, Protestant Nationalists (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1985), where the Colony started by the Markievicz’s and Hobson at Belcamp House in North Dublin is also related (p.37).

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, ftn., pp.815-16, in reference to Yeats’s poem: ‘The gazelle is Eva ... poet, later trade union organiser in Britain’.

Cathach Books, Cat. No. 12, lists a copy of Maurice Maeterlinck, Aglavaine and Selysette, a play in five acts (1891), signed by C. Gore-Booth, with ded. in French on frontleaf.

[ top ]

Notes

The Memory of the Dead, a play by Countess Markievicz for the the Irish Repertory Co., concerns a rebel leader who is saved by a patriot girl. In real life Helena Molony, who played the girl, prayed over Sean Connolly, who played the hero, as he lay dying, the first casualty of the 1916 Rising.

Huckster’s loins?: A contemporary caricature of Countess Markievicz represents her as ‘Madame Przemysl’ denoting trade in Polish [information supplied by Simon Milligan, UUC.]

Aristo-cat?: Marcus Wheeler (Belfast) writes to The Irish Times (25 July 2002) in response to an earlier letter from Sir Jocelyn [var. Josslyn] Gore-Booth about the titled status of his great-aunt Constance following her marriage in 1900 to the Polish painter and playwright Kazimierz [Casimir] Markiewicz: ‘He rightly casts doubt on Markiewicz’s claim to have been a Count. Authoritative Polish sources state that the Markiewicz family belonged to the szlachta or gentry and that - perhaps by virtue of this - Kazimierz certainly used the title of “Count”, but without right. In fact, it appears, this title was not native to Poland; and Poles could have acquired it legitimately only as citizens of the Russian or Austro-Hungarian Empires or as recipients of an honour conferred by the Holy See.’

Lissadell Hse.: See The Gore-Booths of Lissadell (Woodfield Press 2004) - reviewed by Maurice Harmon in Books Ireland, May 2005, p.120 - and note under Eva Gore-Booth, supra.

Gun-play: A photograph of Con Markievicz standing in a field, purportedly at the age of 90 and aiming a revolver in company with Miss Barton (the sis. of Robert Barton), who is watching the demonstration, was offered for sale by Niall Dolan at Rochestown Park Hotel, Cork, in 2011 for an expected €600-800. (See Irish Times, 22 Jan. 2011.)

Lissadell, home of the Gore-Booth family, overlooking the sea between Sligo townand Raghley head, near Drumcliff ...

|

Orig. built between 1750 and 1760, Lissadell underwent radical changes during tenure of Sir Robert Gore-Booth, who was chairman of local grand jury in the early 19th century. Sir Robert demolished the old house, rebuilding it on higher ground 700 metres back from the sea with a new network of roads and avenues and an access tunnel for servants and tradesmen approaching and leaving the the house [known as a “ha-ha”]. He also added 555 acres to the demesne, bringing the whole estate to 32,000, and evicted 120 families in the process, purportedly paying their passage to Canada. [A crowd ship is said to have sunk in Sligo Bay with loss of life in the process - see infra] Sir Jocelyn Gore-Booth, the sixth baronet, sold 28,000 acres to the Land Commission in 1904 and continued to employ up to 200 persons on the remaining estate, running enterprises there which included a munitions factory during World War I. In 2003, Lissadell was purchased by Eddie Walsh and Constance Cassidy, a married couple of practising barristers who paid £4 million for it and subsequently spent €9.5m on its restoration. In so doing they locked gates to block rights of way across their land. There then followed a legal battle with Sligo County Council, spurred on by local action committee at the end of which High Court Judge Bryan MacMahon found that there had indeed been a ‘dedication’ of rights of way in the public favour. In an ensuing appeal case lasting 57 days in court, Supreme Court judges Niall Fennelly, Liam McKechnie, and John MacMenamin overturned the earlier judgement on the grounds that insufficient time had lapsed to assert such a dedication. In an article on the case, Vincent Browne objected that both judgements placed reliance on English jurisprudence rather than the irish constitution’s insistence on the rights of private property and their restraint in the light of common good, noting that the case turned on the period during which ‘available evidence’ could be established for the presumption of a dedication. (See Browne, ‘Lissadell ruling reflects reliance on English law’, in The Irish Times, [Wed.] 20 Nov. 2013, p.16.) |

Follow-up: The Irish Times reports that members of the Sligo county council are furious that the council is now facing a legal bill estimated at between €5 million and €7 million and seeking sight of the legal advice on which the action was taken by the Council - which denies that they started it, though faced with a brief statement from the owners of the house asserting that the Council forced knowingly forced them into litigation spurred on by a minority local action group contrary to wider opinion and the best interests of both the owners and the wider Sligo community. (See ‘Lissadell owners say council report is a “whitewash”’ in The Irish Times, 28.04.2014 - online.)

[ top ]

A Constance Markievicz Gallery

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bernadette Devlin - On 17 April 1969 Devlin, aged 21, became the youngest woman ever elected to the House of Commons. In her maiden speech, she said: ‘I stand here ... in the same tradition as the first woman ever to be elected to this Parliament, Constance Markievicz.’ (See This Day in Irish History - Facebook [17.04.2019].)

| Pomona/Pomano |

See the hostile account of Sir Robert Gore-Booth of Lissadell and the Pomano shipwreck in which many forced emigrants drowned on Sligo Heritage website - online; accessed 04.09.2021. In it, the voayage of the ship and its unregistered name - given as Pomona - are asserted against the evidence of its non-existence on the shipping records and contemporary reports. |

See also Kevin Myers’s account of the imaginary nature of the Pomona story in his Irishman’s Diary (The Irish Times, 31 Jan. 2005) and letters by Joe McGowan and Dermot James on the question in ensuing days. James - the author of the book on the Gore-Booths which Myers cited - writes to the Editor: |

|

| Dermot James, Clonskeagh, Dublin 14; in The Irish Times - online; accessed 04.09.2021. |

| Note also that the Canadian Archive of Emigration contains letters “put in by Sir Robert Gore-Booth” which includes communications from the captains of ships employed by him to carry tenants to Canada with accounts of the superior conditions of the vessel Aeolus to those employed by other, and also about the attempt to find employment for the arrivees and and the reluctance of some to cooperate in the search. Among the 18 letters, some express thanks to Sir Robert for his part in the emigration and others speak of the ease met with in finding employment in their new home. (See Canadian Immigrant Letters > Sir Robert Gore Booth (1946-49) > in British Parliamentary Papers, Emigration, v.5, 122-132, in Canadian National Archinves - online; accessed 04.09.2021.) |

[ top ]