Life

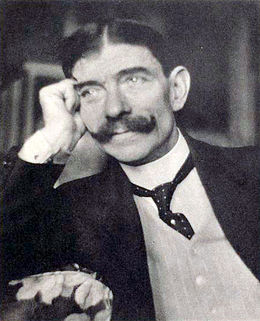

| 1855-1931 [James Thomas Frank Harris; b. 14 Feb. 1855 by his own account, recte 1856;] son of British naval officer; b. 14 Feb., prob. b. in Galway; ‘a Welsh Celt’, in his own account; living in Kerry at 2; mother died when he was 4; moved to Kingstown [Dun Laoghaire], and later in Galway and Belfast, with his brother Vernon; brielfy united with brs. and sisters in Carrifgerdus at 10; ed. Royal Grammar School, Armagh and an English grammar school; ran away to US at 14; worked as bootblack, hotel clerk, and cowpuncher; attended Kansas State Univ.; travelled continent; studied at Heidelberg; settled London; ed. Evening News, 1882-86; ed. Fortnightly Review 1886-94; m. Mary Edith Clayton, widow, 1887; eloped with Helen O’Hara, 1894; later married; ed. Saturday Review, 1894-98; published Shaw, Beerbohm, and Wells; his extrovert arrogance made him enemies; his later editorships were with less prestigious papers in England and America from 1910, incl. Hearth and Home, 1911-12, and Modern Society, 1913-14; he opposed Britain in World War I and was imprisoned for contempt of court, release in 1914, travelling to America where he associated with G. S. Viereck, a virulently pro-German propagandist, issuing England or Germany (NY 1915); |

| ed. Pearson’s Magazine, 1916-22; iss. issued Contemporary Portraits (1915-20), which incls. sketches of John Tyndall, James Larkin, H. L. Mencken & Ernest Haeckel; issued The Bomb (1908), a novel set in Chicago, with an intro. by J. Dos Passos; wrote a successful 4-act play, Mr. & Mrs. Daventry (1900; publ. 1956), from a scenario sold twice over by Wilde; adopted psycho-analytical approach in The Man Shakespeare (1909); issued lives of Wilde (1916) and Shaw (1931); also his tell-all autobiography My Life and Loves, 4. vols. (1922-27), the first volume appearing with plates of ‘pretty, naked girls’ - as he recalls in the preface to the second - epitomising his fight against Victorian prudery; a 5th vol. issued based on MS in Texas HRC was edited by J. F. Gallagher (NY 1963), who condemns a Paris 5th vol. as spurious; [err. 5 vols. 1923-27 DIB;] lived at Nice for some years before his death; d. 27 Aug., bur. Cem. Caucade, Nice; there is a biography by Kingsmill, one time employee (1932); Oscar Wilde reissued 1938, at behest of Harris’s widow, in an edition revised by with a ‘Preface’ by him defending Harris against the charges of Robert Harborough Sherard who attacked his biography as an ‘imposture’ although Shaw discovers the same thing that he objects to said in a biography of his own; the definitive edition was produced by J. F. Gallagher, using the manuscript of the fifth vol. and Harris’s annotated copies of My Life and Loves at the Humanities Research Centre, University of Texas. ODNB DIB DIW KUN OCEL SUTH G20 DUB OCIL |

Harris’s editorial posts: Evening News, 1882-86; Fortnightly Review, 1886-94; Saturday Review, 1894-98; Candid Friend, 1901-02; Vanity Fair, 1907-10; Hearth & Home, 1911-12; Modern Society, 1913-14; Pearson’s Magazine, 1916-22; View of Truth, 1927-28. (For full list of works by and on Harris, see Frederick Bateson, The New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, Vol. 5 (1966), pp.1053-55 - available at Google Books online; accessed 28.05.2011.] |

|

[ top ]

Works| Fiction |

|

| Non-fiction |

|

| Plays |

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Oscar Wilde: His Life and Confessions (NY [priv.]: 1916); Do. [rep. edn.] (NY: 1918); and Do. (1920), incl. ‘My Memories of Oscar Wilde by George Bernard Shaw’ [rep. as appendix]; Do. (NY [Garden City]: Crown Publ. Co. 1930); Do. [rev. edn.], with introduction by Shaw [accounting for changes] (London: Constable 1938); Do. [as] Oscar Wilde (Michigan State UP 1959), and Do. [rep. of 1959 edn.] (Robinson Publ. Co. 1992); 384pp.; Do., [rep. edn.], with a preface by Merlin Wilde (London [q. pub.] 1997).My Life and Loves, 4 vols. (1922-27); J. F. Gallagher, ed. & intro., My Life and Loves, 5 vols. in 1 (NY: Grove Press; London: W H Allen 1964) 983pp. [2nd & 3rd impressions in Oct., Dec. 1964]. Note that Edn. of 1964 lists copyright Frank Harris 1925; Nellie Harris 1953; Arthur Leonard Ross, as exec. of the Frank Harris Estate, 1963, and acknowledges quotations from J. M. Keynes, The Economic Implications of Peace (1920) on pp.958-63. CONTENTS - VOL I: My Life and Loves [10]; Life in an English Grammar School 23]; School Days in England 35]; The Great New World [64]; Life in Chicago [76]; The Great Fire of Chicago [93]; Back on the Trail [98]; Student Life and Love [110]; Some Study, More Love [124]; At the Age of Eighteen [137]; Hard Times and New Loves [151]; New Experiences: Emerson, Walt Whitman, Bret Harte [165]; Law Work and Sophy [179]; Europe and the Carlyles [193]; Afterword to the Story of My Life [212]. VOL. II: Forward [217]; Skobelef [226]; How I Came to Know Shakespeare and German Student Customs [234]; German Student Life and Pleasure [241]; Athens and the English Language [262]; Love in Athens, and “The Sacred Band” [272]; Holidays and Irish Virtue! [283]; How I Met Froude and Won a Place in London and Gave up Writing Poetry!’ [294]; First Love; Hutton, Escott, and the Evening News [310]; Lord Folkestone and the Evening News; Sir Charles Dilke’s Story and His Wife’s; Earl Cairns and Miss Fortescue [319];; London Life and Humor; Burnand and Marx [334]; Laura, Young Tennyson, Carlo Pellegrini, Paderewski, Mrs. Lynn Linton [342]; The Prince; General Dickson; English Gluttony; Sir Robert Fowler and Finch Hatton; Ernest Beckett and Mallock; The Pink ‘Un and Free Speech [352]; Charles Reade; Mary Anderson; Irving; Chamberlain; Hyndman and Burns [368]; The New Speaker Peel; Lord Randolph Churchill; Col. Burnaby; Wolseley; Graham; Gordon; Joke on Alfred Austin [384]; Memories of John Ruskin [397]; Matthew Arnold; Parnell; Oscar Wilde; The Morning Mail; Bottomley [408]; The Ebb and Flow of Passion! [426]; Boulanger; Rochefort; The Colonial Conference; Jan Hofmeyr; Alfred Deakin; And Cecil Rhodes; The Cardinals Manning and Newman [433]; Memories of Guy de Maupassant [443]; Robert Browning’s Funeral; Cecil Rhodes and Barnato; A Financial Duel; Actress and Prince at Monte Carlo [459]; Lord Randolph Churchill [471]; A Passionate Experience in Paris: A French Mistress [492]; The Foretaste of Death from 1920 Onward [500 ]. VOL. III: Foreword [517]; Mental Self-Discipline [525]; Heine [536]; Marriage and Politics [546]; Laura in the Last Phases [554]; Bismarck and Burton [561]; The Evening News [572]; My Pleasures: Driving, Food and Drink, Music and Science [580]; Tennyson and Thomson [591]; Friends [601]; Grace [612]; Parnell and Gladstone [621]; The Fortnightly Review [632]; Prize-Fighting [645]; Queen Victoria and Prince Edward 655]; Prince Edward [671]. VOL. IV: How I Began to Write [683]; The Saturday Review [701]; The Jameson Raid - Rhodes and Chamberlain [712]; African Adventures and Health [731]; Dark Beauties [741]; Barnato, Beit, and Hooley [750]; The South African War: Milner and Chamberlain; Kitchener and Roberts [761]; San Remo [774]; The Girls’ Confessions [785]; Celebrities of the Nineties [793]; Jesus, the Christ [804]; The End of the Century [813]; Sex and Self-Restraint [822]; The Prosecution of My Life [834]. VOL. V: Foreword [847]; there follows numbered but untitled chapters [I 854]; [II 863]; [III 872]; [IV 882]; [V 889]; [VI 893]; Can Personal Immortality Be Proven? [897]; [III 903]; [IX 908]; [X 913]; [XI Maurice Maeterlinck, Wells, Frederic Howe, and Sir John Gorst [917]; [XII]; Ellen Terry and Sarah Bernhardt; Lord Grey, Rochefort and Rudyard Kipling; Marcelin Berthelot [922]; [XIII 929]; [XIV 935].

Note: Gallagher’s Preface [footnotes] to My Life and Loves [5 vols. in 1] (London: W. H. Allen, 1964) lists works by Harris: Elder Conkin and Other Stories (London 1894); The Man Shakespeare, His Tragic Life Story (London 1909); Shakespeare and His Loves (London 1910); The Women of Shakespeare (London 1911); Unpath’d Waters (London 1913); Great Days (London 1914); The Yellow Ticket and Other Stories (London 1914); England or Germany (NY 1915); Contemporary Portraits (London 1915); Youth in Love (NY 1916); Contemporary Portraits, 2nd ser. (NY 1919); Contemporary Portraits, 3rd ser. (NY 1920); Contemporary Portraits, 4th ser. (NY 1923); Undream’d of Shores (NY 1924); Latest Contemporary Portraits (NY 1927); My Reminiscences as a Cowboy (NY 1930); Confessional (NY 1930); Pantopia (NY 1930); Bernard Shaw (NY 1931). Plays include Mr and Mrs Daventry (1899-1900); Joan la Romée (NY & London 1926).

[ top ]

Criticism

|

Note: A listing of works on Harris in Frederick Bateson, New Cambridge Bibliography of English Literature, Vol. 5 (Cambridge 1966), p.1055 - incls. memoirs by H. L. Mencken, Hugh Kingsmill [pseud.], J. M[iddleton] Murry, A. A. Baumann, and O. Cargill; F. Carrell, The Adventures of John Johns (1897) [fictional account of Harris at the Fortnightly Review]; O. Burdett, ‘Writing of Harris’, in Critical Essays (1925); G. Smith & M. C., ed., Lies and Libels of Frank Harris (1929); S. Roth, The Private Life of Harris (1931); F. J. X. Scully, in Rogue’s Gallery (1943); A. Woollcott, ‘The Last of Harris’, in Portable Woollcott (1946); A. Harris Mordell, & Haldeman-Julius, The Record of a Series of Quarrels, Without Equal in the Annals of American Literature (Kansas [1950]; Louis Marlow [pseud.]; J. M. Ross, A Visit to the Villa Edouard Sept, in London Magazine, 2 (1957); V. Brome, The Five Faces of Harris, in Saturday Book, 19 (1959); S. Stokes, Portraits of Frank Harris in Exile, in Listener (5 Dec. 1957). |

|

[ top ]

Commentary

John O’Donovan, Shaw and the Charlatan Genius (Dolmen 1965): ‘[T]he Frank Harris biography, which Shaw half-jokingly, but whole-earnestly used call his ‘autobiography by Frank Harris’, occurs the very curious passage, ‘all through, from his very early childhood, he had lived a fictitious life through the exercise of incessant imagination [...] it was a secret life, its avowal would have made him ridiculous. It had one oddity. The fictitious Shaw was not a man of family. He had no relations. He was not only a bastard, like Donois or Falconbridge, who at least knew who their parents were; he was also a foundling.’ Where can the author of the book have got so intimate a confession except from Shaw himself? And if Shaw did not write the actual words, he passed them without contradiction.’

Stan Gèbler Davies, James Joyce: A Portrait of the Artist (London: David Poynter 1975), writes of visitors to Sylvia Beach’s shop after the publication of Joyce’s Ulysses: ‘Frank Harris appeared in a horse-drawn cariage, especially hired for the occasion to impress Miss Beach, and offered her My Life and Loves, that immensely long and mendacious account of bogus conquests and non-existent friendships with the great. It went much further than Joyce, he assured her. Miss Beach sent him on to Kahane, but could not resist a little joke. When Harris, running once to catch a train, asked for an “exciting” book she gave him Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women. [...] “The Beast” [Crowley], too, turned up with the offer of his memoirs.’ (p.244.)

John Jordan: ‘The biography of Bernard Shaw by Frank Harris contains an admirable letter by the former [...] “I understand everything and everyone and I am nothing a[n] no one’. From this nothingness (so comparable to that of God before creating the word, so comparable to that primordial divinity which another Irishman, Johannes Scottus Eriugena, called Nihil) Bernard Shaw enduced almost innumberable persons or dramatis personae, the most ephemeral of these is, I suspect, that of GBS who represented him in public and who lavished in the newspaper columns so many facile witticisms [...] The work of Shaw [...] leaves one with a flavour of liberation, the flavour of the stoic doctrines and the flavour of the sagas.”’ (On Shaw, Wilde, Synge and Yeats, in Richard Kearney, ed., The Irish Mind, 1985, p.212f.)

Merlin Holland, ‘Not unkind and not untrue’, in Times Literary Supplement (24 Oct. 1997), p.17 [full page re-evaluation of his ‘technicolour’ life of Wilde]; his life of Wilde dismissed as ‘fabrications’ by Lord Alfred Douglas and Robert Sherard, whom Wilde met in Paris in 1883, and who became his most voluminous and spaniel-like biographer; Harris answered with Oscar Wilde Twice Defended (1934) and Bernard Shaw, Frank Harris, and Oscar Wilde (1937); notes that Harris, not Hesketh Pearson, as noted in Ellmann, is the original source of the exchange between Wilde and Whistler ending with Whistler’s retort, ‘you will, Oscar, you will’; Harris’s The Life and Confessions of Oscar Wilde published privately, in two editions, in New York but not in London; in 1925, Alfred Douglas visited Harris in Nice, refused to allow it be appear in London without substantial changes, which were incorporated in New Preface to intended to correct Harris’s so-called misstatements, though Douglas is know to have fabricated the new details at a rate of ‘one truth for twenty lies’ (acc. Vyvyan); Douglas published this as a separate work for its value as a retraction of the former accusations; Harris’s widow sought to publish it in 1936, appealed to Shaw, who wrote a long introduction and removed or rewrote with Douglas’s connivance all the offending material; Shaw sent the corrected version to Constable with a note, ‘Here at last is this accursed job done. I think it is lawyer proof now. Far from libelling Douglas it gives him his first coat of whitewash’, and writing similarly at the end of his Introduction: ‘Here is his book, with a few emendations which are now needed to prevent its misleading readers to whom the subject is new.’

For Commentaries on The Bomb (1908) - see attached.

[ top ]

Quotations

Shakespeare (1): ‘It is the life-work of the artist to show himself to us, and the completeness with which he reveals his own individuality is perhaps the best measure of his genius’ (Frank Harris, The Man Shakespeare and His Tragic Life Story, NY: M. Kennerley 1909, p.4.) Further, ‘A great dramatist may not paint himself for us at any time in his career with all his faults and vices; but when he goes deepest into human nature, we may be sure that self knowledge is his guide; as Hamlet said, “To know a man well, were to know himself (oneself)”’ (Ibid., p.7; both cited in Andrew Holland, The Book of Himself: The Shakespeare Theory in Ulysses and its Significance in the Life of James Joyce’ [UU MA Diss., 2000].)

Shakespeare (2): ‘In the foreword to The Man Shakespeare, I tried to show how Puritanism that had gone out of our morals had gone into the language, enfeebing English thought and impoverishing English seep./ At long ast I am going back to the old English tradition. I am determined to tell the truth about my pilgrimage through this world, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, anout myself and others, and I shall try at least to be as kindly to others as to myself.’ (p.2). ‘I had come to a sort of impasse in my work; I saw the whole assumption that Shakespeare had been a boy lover, drawn from the sonnets, was [775] probably false, but since Hallam it was held by every one in England, and every one, too, in Germany, so prone are men always to believe the wrost, especially of their betters - the great leaders of humanity.’ Life and Loves, p.775-76.)

Oscar Wilde (Harris reports Wilde’s reputed remarks to him): ‘When I married, my wife was a beautiful girl, white and slim as a lily, with dancing eyes and gap, rippling laughter like music. In a year or so the flowerlike grace had all vanished; she became heavy, shapeless, deformed. She dragged herself about the house in uncouth misery with drawn blotched face and hideous body, sick at heart because of our love. It was dreadful. I tried to be kind to her; forced myself to touch and kiss her; but she was sick always, and - oh! I cannot recall it, it is all loathsome [...] I used to wash my mouth and open the window to cleanse my lips with fresh air.’ (Oscar Wilde, Life and Confession, priv. 1916, pp.337-38; quoted in Fionnula Henderson, “Oscar Wilde and Aestheticism: A Study of the Social Comedies”, UG Disseration on Wilde, UUC [2001].)

G. B. Shaw: Frank Harris on Bernard Shaw (1931): begins with a series of letters from Shaw, which Harris construes as melting resistance. Shaw’s remarks are acerbic, ‘A man cannot take a libel action against himself’; ‘I can imagine nothing more ghastly than a literary shepard’s pie with Harris and Shaw horribly messed up together’ [15]; Shaw was ‘a charming talker with enough brogue to make women appraise him with an eye to capture.’ [31] On Shaw, ‘[He] handled English with the Irish advantage of catching it in its Augustan phase, then a century out of date in England’ (p.43). “Ireland in the ’Sixties” [chap.] is a Shavian celebration of the paradox of Irish character, but also a paeon to the spirit of the late nineteenth century Irish contribution to the English world in the form of soldiers, writers, and statesmen, including Moore, Wilde, Redmond, Boucicault, Casement, Roberts and Kitchener, T P O’Connor, Carson, [Francis] Fahy, Fanny Parnell; Harris expressly claims to have been born in Ireland. Note GBS, in his postscript to the ‘unauthorised biography’: “I never discussed sex with Frank Harris, because his intolerant Irish-American prudery - the last quality he ever suspected in himself - made complete and dispassionate discussion impossible. He never could understand why I insisted that his autobiographical Life and Loves, which he believed to be the last word in out-spoken self-revelation, told us nothing about him that was distinctively Frank Harrisian, and showed, in one amusingly significant passage, that there is a Joseph Conrad in every Casanova.” (G. B. Shaw, 1931, p.396.)

[ top ]

My Life and Loves (1922): - ‘The religion that directed or was supposed to direct our conduct for nineteen centuries has been finally discarded. Event the divine spirit of Jesus was thrown aside by Nietszche as one throws the hatchet after the helve, or to use the better German simile, the child was thrown out with the bathwater. The silly sex-morality of Paul has brought discredit upon the whole Gospel. Paul was impotent, boasted indeed that he had no sexual desires, wished that all men were even as he in that respect, just as the fox in the fable who had lost his tail wished that all other foxes should be mutilated in order to attain his perfection.’ [My Life &c., 1964 Edn.; p.6.] Further, ‘We are beginning to reject Puritanism and its unspeakable, brainless pruderies; but Catholicism is just as bad. Go to the Vatican Gallery and the great Church of St. Peter in Rome and you will see the fairest figures of ancient art clothed in painted tin, as if the most essential organs of the body were disgusting and had to be concealed. / I say the body is beautiful and must be lifted and dignified by our reverence: I love the body more than any Pagan of them all and I love the soul and her aspirations as well; for me the body and the soul are alike beautiful, all dedicate [sic] to Love and her worship. / I have no divided allegiance and what I preach today amid the scorn and hatred of men will be universally accepted tomorrow; for, in my vision, too, a thousand years are as one day. /We must unite the soul of Paganism, the love of beauty and art and literature with the soul of Christianity and its human loving-kindness in a new synthesis which shall include all the sweet and gentle and noble impulses in us.’ (John F. Gallagher, ed., Life & Loves, 1964, Vol. 1, p.7.) [See further under Gladstone, q.v.]

My Life and Loves (1922) - cont.: ‘No doubt my small stature helped the effect and the Irish love of rhetoric did the rest; but everyone praised me and thshowing off made me very vain …. I was soon lost in this new workd, though I played at school with the oother boys, in the evening I never opened a lesson-book. Instead, I devoured [Charles] Lever and Mayne Reid, Marryat, and Fenmore Cooper with unspeakable delight. / I had one or two fights at school with boys of my own age … The Irish are supposed to love fighting better than eating; but my school days assure me, however, that they are not nearly so combative, or perhaps, I should say, so brutal, as the English. / … I still remember the feeling of horror his confession called up in me: “A Roman Catholic! Could anyone as nice as Howard be a Catholic?’ (p.17; note that Lever and Mayne are listed as ‘English writers of adventure novels’, in ftn.).

Further: ‘I was thunderstruck and this amazement has always iluminated for me the abyss of Protestant bigotry, but I wouldn’t break with Howard, who was two years older than I and who taught me many things. One day I remember he showed me posted on the court house a notice offering £5,000 reward to anyone who would tell the where-abouts of James Stephens, the Fenian head-centre. “he’s travelling all over Ireland”, Howard whispered. “Everyone knows him”, adding with gusto, “but no one would give the head-centre a way to the dirty English.” I remember thrilling to the mystery and chivalry of the story. From that moment, head-centre was a sacred symbol to me as Howard.”’ (p.18); goes on to narrate the older boy Strangeway’s ejaculation and his tale of getting into bed with a children’s nurse and having sex with her: ‘Nothing in my life up to that moment was comparable in joy to that story of sedual pleasure as described, and acted for us, by Strangeways.’

My Life and Loves (1922) - cont.: Harris describes himself as a Welsh Celt [Life &c., p.236]; ‘Irish Virtue’ (Chap.): ‘How is it that the Irish come to have this insane belief in th necessity and virtue of chastity? It is their unquestioned religious belief that gives it them, yet in the mountains of Bavaria and in parts of the Abruzzi, the peasants are just as religious, and there, too, chastity is highly esteemed, but nothing to be compared to its power in Ireland. I’ve often wondered why?’ [Life, p.292.] ‘I found it difficult, not to say impossible, to get any sex-knowledge from Laura. Like most girls with any Irish strain in them, she disliked talking of the matter at all.’ [ibid., p.350.] ‘In my experience, incest is infinitely commoner among the Germanic peoples than it is among the Latins or Slavs. It is curious that in spite of the poverty and the fact that in some homes large families have to live in one room, incest is almost unknown among the Celts. But then I am of the opinion that the Irish and the Scotch and even the Welsh Celts are far more moral in the highest sense of the word than their English neighbours.’ [Ibid., p.833.]

[ top ]

References

John Sutherland, The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (Longmans 1988; rep. 1989), does not cite a birthplace; gives name as James Thomas Harris, born son of Welsh seaman, ran away to USA at 14, and drifted; Kansas State Univ., 1872; genius for journalism; London, 1883; ed. Fortnightly Review by 1886; m. Park Lane widow, and embarked on career as socialist; eloped with Helen O’Hara, 1894, and later married. Elder Conklin and Other Stories (1894), includes vivid account of rough life in Kansas’, and gunslinging stories; bought Saturday Review, 1894, and sold in 1898; failed at luxury hotels on the Riviera; prison spell in later life; My Life (1922-26), fascinating, scandalous and unreliable; Montes The Matador (1900), second vol. of fiction, incl. an authentic tale of the corrida, and the story of a young MP’s infatuation with a Russian nihilist. BL 4.

Berg Collection of New York Public Library holds works of Harris incl. The Bomb (NY: Kennerley 1909), [signed presentation copy], et al., all ex. collection of F. R. Little.

[ top ]

Notes

Oscar Wilde dedicated An Ideal Husband to Harris: ‘to Frank Harris, a slight tribute to his power and distinction as an artist, his chivalry and nobility as a friend’]. But note that Harris described Sir William Wilde as a ‘pithecoid person of extraordinary sensuality and cowardice’. (Oscar Wilde (Constable 1964); cited in Victoria Glendenning, ‘Speranza’ (Times Literary Supplement, 16 May 1980; see Lady Wilde, infra). Note Juan Luis Borges use of Shaw’s correspondence with Harris, rep. in Harris’s Shaw (see Shaw, infra.)

J. F. Gallagher, My Life and Loves (London: W H Allen 1964): Journals edited by Harris in England and America after 1910 were Hearth and Home, 1911-12; Modern Society, 1913-14; Pearson’s, 1916-22; View of Truth, 1927-28.G. B. Shaw was dramatic critic on Saturday Review, under the editorship of Harris in 1895; Harris aimed at socialist premiership; made Saturday Review most brilliant weekly of its time; ruined reputation with later journalistic ventures; lives of Wilde (1916), Shaw (1931), and My Life (1925-30) ‘reveals delusions of greatness’ [ODNB]; his Oscar Wilde condemned for supposed unfairness to Lord Alfred Douglas, while attacks also from defenders like Ross and Robert Sherard.

[ top ]