| Life | ||||

| 1728: b. 10 Nov., Pallasmore [Pallas], Forgney, Co. Longford (or poss. Ardnagowan near Elphin); a forebear called John Goldsmith was rector of Bourishoull, Co., Mayo, in 1641 and narrowly escaped death in the rebellion [‘Popish massacre’]; Oliver was 2nd son [var., 3rd son among four: Poetical Works, 1804] of a poor Anglican clergyman, and Anne Jones, dg. of Oliver Jones, of Smith Hill House, who was head of diocesan school at Elphin; had a br. Charles, who later followed him to London; the family moved to Lissoy on his father receiving the living of Kilkenny West, nr. Ballymahon, Co. Westmeath, 1730; ed. Lissoy [autograph var. Lishoy], under Thomas Byrne, and diocesan school of Elphin, Co. Roscommon; also briefly at Athlone, and later at Edgeworthstown under Rev. Patrick Hughes; contracts smallpox; enters TCD as a sizar, 11 June, 1745 [var. 1744], his tutor being Theaker Wilder, a mathematician; | ||||

| attends plays at Royal Theatre and neglects studies; falls to bottom of his class in theology and law; suffers death of his father 1747, after which the house at Lissoy passed to Mr. Hudson, married to OG’s sister Catherine; his mother settles at Ballymahon, in straightened circumstances; his br. Henry became curate in his father’s former living, taught school, living at Pallas - establishing a happy family and a reputation for kindness; OG put under the charge of an uncle, Contarine; makes money by selling songs to Hicks for printing [vide Colm Ó Lochlainn, More Irish Street Ballads, 1965]; friendship with college friend Robert Bryanton, the scion of Ballymulvey House, led to frolics in neighbourhood of Ballymahon; | ||||

| wins college prize, and riots with the money by conducting a party with town women in his rooms; knocked down by his tutor, Wilder, and quits college; his re-entrance to college secured by his br. Henry, then already in orders; formally admonished in connection with the Black Dog riot, which left two townspeople dead and resulting the explusion of four students; grad. 27 BA Feb. 1749 [O.C. - vars. 1748; 1750, Swarbrick, ed.]; sets out walking to Cork with view to emigration, but turns back for Lissoy after three days, 1749; suffered a rift with his mother (‘I have a sneaking fondness for her still’); rejected for Holy Orders by Bishop of Elphin because of inappropriateness of his dress (red breeches), 1751; supplied with £50 by an uncle to study law in London (Inner Temple) but loses it on cards in Dublin; goes to Edinburgh to study medicine, again supported by his uncle, Sept. 1752-Feb. 1753; attends soirées of Duke of Hamilton and is regarded as ‘the facetious Irishman’; imprisoned Newcastle on suspicion of recruiting for French; | ||||

| 1755: OG travels to continent and remains at Leyden until 1755; wanders in France, Switzerland, and Italy, 1755-56 (‘remote, unfriended, melancholy, slow’); perhaps becomes MD at Louvain or Padua; visits Voltaire at Lausanne; returns to England, arriving at Dover, 1 Feb. 1756; reaches London destitute; sets up as physician in Southwark, and takes teaching work at Dr. Milner’s school at Peckham; there meets the publisher Ralph Griffiths and commences writing for the Monthly Review, 1757, producing more than 90 notices, including a review of Burke’s Philosophical inquiry ... into the sublime and beautiful; seeks employment as surgeon’s mate in the Royal Navy, and found not qualifed at examination, 21 Dec. 1758; OG parts with Griffiths after seven months, accusing him of ‘falsifying’ his writing, 1759; engaged by Smollett on British Magazine, 1759; issues first independent work, Memoirs of a Protestant, condemned to the Galleys of France, for his Religion, a translation; fails to qualify for med. post in India Company, 1758; issues Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning (April 1759), makes acquaintance with Bishop Thomas Percy of Reliques fame, who would later write Memoir of Goldsmith (1801); OG writes short life of Bishop Berkeley, replete with Irish anecdote (1759); contribs. to Critical Review et al.; contribs. article on Carolan to British Magazine (July 1760); | ||||

| 1760: encounters John Newbery and worked for him on the Public Ledger, his first piece appearing 12 Jan. 1760; OG occupies upper room in Newbury’s home, Canonbury House, Islington at times during 1760-69; 123 “Chinese Letters” published in the Public Ledger, 1760-62, later collected as Citizen of the World; or Letters from a Chinese Philosopher residing in London to his Friends in the East (1762) and containing the characters Beau Tibbs, Mrs Tibbs, and ‘the Man in Black’, a self-portrait [1761]; moves from Green Arbour Court to better rooms at Wine Office Court, Fleet St.; becomes acquainted with Garrick, Murphy, Smart, Bickerstaff, and a member of Johnson’s Club, 1760; entertains a party incl. Percy and Johnson, 31 May 1761; writes abridgement of Voltaire (1761); writes a Life of Beau Nash (1762); experiences illness and visits spas, 1763; first meets Boswell, who disparaged him in his Life of Johnson, 1763; issued History of England in a Series of Letters from a Nobleman to his Son (1764), anonymously published and attributed on style to Chesterfield, Lord Orrery, and Lord Lyttleton [var. Aug. 1771 CAB]; secures patronage of Lord Clare with his Traveller, or a Prospect of Society (Dec. 1764), the first work to appear under his own name, and compared by Johnson to work of Pope; receives £20 for the poem, which Newbery sold through numerous editions; moves from Wine Court to the Temple; reputedly wrote Goody Two Shoes; | ||||

| 1765: an edition of his collected essays printed in 1765; enters dispute with a chemist over a prescription, being ejected from the house of a lady he had offered to help as a physician, 1765; Boswell reports that Johnson visited him in poverty and removes the manuscript of The Vicar of Wakefield for sale; known to have been purchased by Newbery with Collins and another, for £21 on 21 Oct. 1762, the copyright being sold to Francis Newbery, nephew of John, at a profit of £63; not published until 1766 (96th edn. 1889), probably in view of sale of The Traveller; Vicar of Wakefield quickly running to three editions during 1766, the fourth edn. starting at a loss; wrote a short English grammar for five guineas; wrote History of Rome (1769) [var. Roman History], for booksellers; death of Newbery, 1767; | ||||

| 1767: The Goodnatur’d Man was rejected by Garrick in favour of a comedy by Hugh Kelly, 1767, and then taken up by Colman the Elder to be performed at Covent Garden, 1768, with a gloomy prologue by Johnson who attended the rehearsals as an encouragement; ran for ten nights only; printed with a Preface attacking the fashion for sentimental drama or ‘genteel comedy’, supposedly by Goldsmith himself but probably by Arthur Murphy; used proceeds, c.£500, from play and publication, to move to newly-furnished chambers; occupied cottage on Edgeware Rd., returning in October; published History of Rome (May 1769); issued The Deserted Village (26 May 1770), running to a fifth edition by August; issued Life of Parnell (1770); travelled to Paris with the Horneck family (Mrs Horneck, Mary, and Catherine, 1770, Mary, whom he met at 14, being his ‘Jessamy Bride’ (later m. H. W. Bunbury); writes The Haunch of Venison, a poetical epistle to Lord Clare (publ. posthum 1776), in return for a gift of Lord Clare; agreed with Davies to write a Life of Bolingbroke (Dec. 1770); | ||||

| 1773: published anonymously “An Essay on the Theatre; or, A Comparison between the Laughing and Sentimental Comedy” in Westminster Gazette (Jan. 1773, pp.4-6), criticising the latter; increasingly plunged in death through expensive living; She Stoops to Conquer (Covent Garden, March 1773), a tale of ‘mistakes of the night’ concerning class confusions, and produced after interventions by Johnson; altercation with Thomas Evans and the editor of The London Packet, in which appeared ‘Tom Tickle’, an insulting letter mocking his tender feelings for ‘the lovely H-k’; | ||||

| 1774: publishes The Retaliation (1774), containing celebrated lines on Burke, Garrick, Cumberland, et al.; The History of Greece (1774); An History of the Earth and Animated Nature, 8 vols. (posthum. 1774), commissioned 1769, and paided for long before delivery, often ridiculed for its preposterous inventions; removed to country lodgings nr. Hyde to write and recoup his fortune; returned ill to London; embarked on “The Retaliation”, and is writing of Reynolds (‘by flattery unspoiled’) at the time when he suffers his final attack;d. 5.00 a.m., 4 April 1774, of strangury (congestion of bladder) and fever; reputed last words, ‘I am not at ease in my mind’; bur. Temple Church, monument at expense of The Club in Westminster Abbey, with Latin epitaph by Johnson (‘qui omnes fere scribendi genus tetigit, et nullum tetigit, quod non ornavit [there was almost no subject he did not write about, and he wrote on nothing without enhancing it]’ - who also remarked to Boswell, ‘Let not his frailties be remembered; he was a very great man’ (Prior, Life of Goldsmith); Samuel Johnson considered Goldsmith ‘a very great man’ and there are extensive references to him in Boswell’s Life of Dr. Johnson - often as a butt to contemporary literary men‘s humour; for Goethe he stood with Shakespeare and Sterne as leading influences; | ||||

Post-hum.: Miscellaneous Works of Goldsmith (1801), with Percy’s Memoir of Goldsmith; Dublin editions of poems and plays in 1777 and 1780; English edns. in 1831 and 1846; an edition of Vicar of Wakefield appeared in 1843 with ills. by William Mulready; the edition of Deserted Village by R. H. Newell (1811), contains the first account of the locality of the eponymous village, with engravings of same by Aitkin; remembered for his kindness to the common people among whom he lived; characterised as consummate booby in Boswell’s Life of Johnson; statue by J. H. Foley at College Green on front of TCD West Gate, 1864; James Prior wrote a life of Goldsmith (2 vols., 1836), to accompany an edition of the Works issued in (4 vols. 1836-37); others were written by Washington Irving (1844), John Foster (1848); Peter Cunningham’s edition of the Works (1854) was the first issue of Murray’s British Classics, and reissued with an introduction by Austin Dobson (1900); it fell to Sydney Owenson [later Lady Morgan], in The Wild Irish Girl (1806), to identify him as an Irish writer whose pen captured the scenes of his native country, a theme reiterated by John Montague and others; a modern edition of The Vicar of Wakefield was ill. by Hugh Thompson; Tom Murphy dramatised The Vicar of Wakefield [c.1975], and adapted She Stoops to Conquer to an Irish setting. RR CAB ODNB PI JMC ODQ DIB DIW DIL OCEL NCBE OCIL FDA |

||||

| [ top ] | ||||

[ Note: The bronze maquette by John Henry Foley was auctioned at Sotheby’s (London) for £23,000 in 2007. ] |

Works

Individual editions, Citizen of the World (1760-61); The Traveller (1764); The Deserted Village (1770); The Vicar of Wakefield (1766); The Good Natur’d Man (1768); An Essay on the Theatre; or, A Comparison between the Laughing and Sentimental Comedy (1773) [anon., Westminster Gazette, Jan. 1773]; She Stoops to Conquer (1774); History of the Earth and Animated Nature, 8 vols. [see also infra]; The Haunch of Venison, a poetical epistle to Lord Clare (London: G. Kearsly & J. Ridley 1776), 4o. Also, Lives of Dr Parnell and Lord Bolingbroke, with The Bee (Belfast 1818), vi, 243pp.

| RICORSO Library, “Irish Classics” - full-text editions | |

| “The Deserted Village” (1770) | The Vicar of Wakefield (1776) |

Collected Editions: The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B., 4 vols. (London: J. Johnson, C. & J. Robinson 1801); R. S. Crane, ed., New Essays by Oliver Goldsmith (Chicago UP 1927); Katherine [Canby] Balderston, ed., The Collected Letters of Oliver Goldsmith (Cambridge UP 1928); Arthur Friedman, The Collected Works of Oliver Goldsmith, 5 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon P. 1966); John Lucas, ed., Oliver Goldsmith, Selected Writings (Belfast: Blackstaff Press 1990); Alan Rudrum & Peter Dixon, eds., Selected poems of Samuel Johnson and Oliver Goldsmith [Arnold’s English Texts] (London: Edward Arnold 1965), 146pp.

Bibliography, Temple Scott, Oliver Goldsmith Biographically and Bibliographically Considered (NY 1928); Katherine Canby Balderston, A Census of the Manuscripts of Oliver Goldsmith (NY 1926).

“Miscellaneous Works” (var. edns.), The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Containing all his essays and poems (London: W. Griffin 1775), iv, [9-]200pp., 8o; another edn. (London: W. Griffin 1778), vi, 225pp., 12o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin 1780; 1782; 1784; 1786), vi, 225pp., 8o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin 1786), 238pp., 12o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin; Gainsbro’: H. Mozley 1789), 238pp.,. 12o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Consisting of his essays, poems, plays [ &c.], 2 vols. (Edinburgh, Perth: R. Morison & Sons 1791), 12o; The miscellaneous works, 4 vols. (Edinburgh: Geo. Mudie 1792), 12o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith; now first uniformly collected, 7 vols. (Perth: R. Morison & Son; Edinburgh: A. Guthrie 1792) plates, port. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Containing all his essays and poems; with an account of the life and writings of the author. A new and correct edition (London: J. Deighton 1793), xli, 288pp., 12o; another edn. (Glasgow: J. & M. Robertson, et al. 1795), another edn. (Boston [Mass.]: Thomas & Andrews, 1795), 237pp. 12o; [Samuel Rose, ed.,] The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. A new edition, To which is prefixed, some account of his life and writings [by Thomas Percy, Bishop of Dromore], 4 vols. (London: J. Johnson, et al. 1801; 1806), pls., port. 8o. . 4 vol.: plates; port. 8o; another edn. (London: W. Otridge & Son, 1812); another edn. (Glasgow: R. Chapman 1816); another edn. (London: F. C. & J. Rivington, et al. 1820); another edn., 6 vols. (London: Samuel Richards 1823), plates; port. 12o; Washington Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings. A new edition. 4 vols. (Paris: A. & W. Galignani; Jules Didot 1825), plate, port., 8o; Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings, stereotyped from the Paris edition (Philadelphia: J. Crissy; Desilver, Thomas & Co. 1836), 527pp., plate; port. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings, 4 vols. (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, &c. 1837), plate; port., 8o; James Prior, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Including a variety of pieces now first collected (London: John Murray 1837), 8o; Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. To which is prefixed some account of his life and writings [extracted from the edition of 1823]; another edn. (Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson 1840), xxii, 458pp., plate, port., 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. With a brief memoir of the author [ &c.] (London: Andrew Moffat; Glasgow: D. A. Borrenstein 1841), xii, 308pp.; illus. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. To which is prefixed some account of his life and writings. A new edition, [etc.] (Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson 1843) xxii, 458pp., plate, port., 8o; James Prior, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, including a variety of pieces now first collected, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866), ill. plates.; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith. With biographical introduction by Professor Masson [The Globe edition] (London & NY: Macmillan & Co. 1869 [1868]; 1871), lx, 695pp., 18cm.

[ top ]

Dublin reprint editions

Poetry

- The Citizen of the World, 2 vols. (Dublin: George and Alex. Ewing 1762); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: J. Williams, 1769); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: the United Company of Booksellers, 1775).

- The Traveller, or a Prospect of Society (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1767); Do., another edn. (Dublin: George Faulkner, 1770). The Deserted Village (Dublin: J. Exshaw, H. Saunders, B. Grierson, J. Potts, W. Sleater, D. Chamberlaine, J. Hoey, Jnr, J. Williams, C. Ingham, J. Porter, and R. Moncrieffe, 1770); Do., another edn. 2nd edn. (Dublin: H. Saunders, B. Grierson, J. Potts, W. Sleater, D. Chamberlaine, J. Hoey, Jnr., J. Williams, C. Ingham, J. Porter, and R. Moncrieffe, 1770); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Messrs. Price, Sleater, W. Watson, Whitestone, Chamberlaine, S. Watson, Burrowes, Potts, Williams, Hoey, Wilkinson, Sheppard, Colles, Wilson, Moncrieffe, Walker, Jenkin, Exshaw, Burnet, Hillary, Wogan, Mills, White, Higly, and Beatty, 1784)

- Poems (Belfast: printed by James Magee 1775); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Charles Downes, for Thomas Reilly, 1801).

- The Haunch of Venison (Dublin: W. Whitestone, W. Watson, W. Sleater, J. Potts, J. Hoey, W. Colles, W. Wilson, R. Moncrieffe, G. Burnet, C. Jenkin, T. Walker, W. Hallhead, W. Spotswood, M. Mills,J. Exshaw, J. Beatty, and C. Talbot, 1776).

- The Deserted Village: A Poem, by Dr Goldsmith [2nd. edn.] (Dublin: printed for J. Exshaw, H. Saunders, B. Grierson, J. Potts, W. Sleater, D. Chamberlaine, J. Hoey, jun. J. Williams, C. Ingham, J. Porter, and R. Moncrieffe MDCCLXX. [1770]), ix, [1], 28pp. [being Todd"s "L" edition cited in ‘The Private Issues of The Deserted Village’, in Studies in Bibliography, 6 (1955), pp.25-44; Eng. Short Title Cat. T145771].

Drama (here mainly Dublin editions)

- The Good Natur’d Man [A Comedy, As performed at the Theatre-Royal in Covent-Garden] (Dublin: J. A. Husband, for J. Hoey, Snr., P. and W. Wilson, J. Exshaw, H. Saunders, W. Sleater, J. Williams, D. Chamberlaine, J. Potts, J. Mitchell, J. Sheppard, and W. Colles, 1768), 70pp. 12o, Do., another edn. (Dublin: J. Hoey, sen., et al., 1770); Do. (Dublin: Messrs. Price, Sleater, W. Watson, Whitestone, Chamberlaine, S. Watson, Burrowes, Potts, Williams, Hoey, Wilkinson, Sheppard, Colles, Wilson, Moncrieffe, Walker, Jenkin, Exshaw, Burnet, Hillary, Wogan, Mills, White, Higly, and Beatty, 1784).

- She Stoops to Conquer: or, The Mistakes of a Night. A Comedy. As it is acted at the Theatre-Royal in Covent-Garden. (Lonon: F. Newbery, in St. Paul's Church-Yard, M DCC LXXIII. [1773]), 106pp. [epilogue by Craddock printed after p.106]; Do. (Dublin: Messrs. Exshaw, Saunders, Sleater, Potts, Chamberlaine, Williams, Wilson, Hoey, Jnr, Husband, Lynch, Vallance, Colles, Walker, Moncrieffe, Jenkin, Flin, and Hillary, 1773); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Exshaw, et al. [excluding Colles], 1773); Do. (Belfast: printed by James Magee 1773); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Bartholomew Corcoran, 1774); Do., (Dublin: Messrs. Price, Sleater, W. Watson, Whitestone, Chamberlaine, S. Watson, Burrowes, Potts, Williams, Hoey, Wilkinson, Sheppard, Colles, Wilson, Moncrieffe, Walker, Jenkin, Exshaw, Burnet, Hillary, Wogan, Mills, White, Higly, and Beatty, 1784); Do., (Dublin: Messrs. Price, et al., 1785); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Graisberry and Campbell, for William Jones, 1792).

Fiction

- The Vicar of Wakefield, 2 vols. (Dublin: W. and W. Smith, A. Leathley, J. Hoey, Snr., P. Wilson, J. Exshaw, E. Watts, H. Saunders, J. Hoey, Jnr., J. Potts, and J. Williams, 1766); Do., another edn. 2nd edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: W. and W. Smith, et al., 1766); Do., another edn. 2 vols. Corke: printed by Eugene Swiney, 1766); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: W. and W. Smith, et al., 1767); Do., another edn. (Dublin: the United Company of Booksellers, 1791); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: printed byJ. Stockdale, forJ. Moore, 1793); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: T. Henshall, [1794]); Do. [trans.]. Le curé de Wakefield (Dublin: G. Gilbert, 1797).

Prose

- Essays. 2nd edn. (Dublin: J. Williams, 1767); Do., another edn. 3rd edn. (Dublin: James Williams, 1772); Do., another edn. 3 vols. (Dublin: J. Stockdale for J. Moore, 1793).

- An History of the Earth and Animated Nature, 8 vols. (Dublin: J. Williams, 1776); Do., another edn. 8 vols. (Dublin: J. Williams, 1777); Do., another edn. 8 vols. (Dublin: J. Williams, 1782-83).

- An History of England in a Series of Letters from a Nobleman to his Son, 2 vols. (Dublin: J. Exshaw and H. Bradley, 1765); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: J. Exshaw and H. Bradley, 1767); Do., another edn. 4th edn., 2 vols. (Dublin: J., Exshaw and W. Colles, 1784).

- The History of England, from the Earliest Times to the Death of George II, 4 vols. (Dublin: A. Leathley, J. Exshaw, W. Wilson, H. Saunders, W. Sleater, D. Chamberlaine, J. Hoey, Jnr., J. Potts, J. Williams, J. Mitchell, J. A. Husband, W. Colles, T. Walker, R. Moncrieffe, and D. Hay, 1771); Do., another edn. 4th edn., 4 vols. (Dublin: W. Sleater, H. Chamberlaine, J. Potts, W. Colles, R. Moncrieffe, T. Walker, W. Wilson, J. Exshaw, and L. White, 1789); Do., another edn. 5th edn. 4 vols. (Dublin: William Porter, for W. Gilbert, P. Wogan, J. Exshaw, W. Porter, W. McKenzie, J. Moore, W. Jones, and J. Rice, 1796); Do., another edn. [as] An Abridgement of the History of England, from the Invasion of Julius Caesar, to the Death of George II. 5th edn. (Dublin: James Williams, 1779).

- The Roman History, 2 vols. (Dublin: S. Powel, J. Exshaw, H. Saunders, B. Grierson, W. Sleater, D. Chamberlaine, J. Potts, J. Hoey, Jnr., J. Williams, and C. Ingham, 1769); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: S. Powel, et al., 1771); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: P. Wogan, J. Exshaw, W. Sleater, J. Rice, and R. White, 1792); Do., another edn. 2 vols. Cork: printed by J. Connor, 1800); Do. [another edn.], The Roman History, abridged for schools (Dublin: P. Wogan, 1798).

- The Grecian History, 2 vols. (Dublin: printed forJames Williams, 1774); Do., another edn. 2 vols. (Dublin: P. Wogan, 1801). [From Richard Cargill Cole, Irish Booksellers and English Writers, 1740-1800 (London: Mansell Pub.; NJ: Atlantic Heights 1986), Appendix 4 [pp.245-47].

Collections

- Poems and Plays (Dublin: Messrs. Price, Sleater, W. Watson, Whitestone, Chamberlaine, S. Watson, Burrowes, Potts, Williams, Hoey, Wilkinson, Sheppard, W. Colles, W. Wilson, Moncrieffe, Walker, Jenkin, Hallhead, Exshaw, Spotswood, Burnet, P. Wilson, Armitage, E. Cross, Hillary, Wogan, Mills, White, T. Watson, Talbot, Higly, and Beatty, 1777); Do., another edn. (Dublin: Wm. Wilson, 1777); Do., another edn. new corrected edition (Dublin: Messrs. Price, et al., 1785).

- The Beauties of Goldsmith (Dublin: J. Rea, for Messrs. S. Price, Walker, Exshaw, Beatty, Wilson, Wogan, Burton, Byrne, and Cash, 1783).

- The Poetical Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with a sketch of the author’s life: including original anecdotes, communicated by The Rev. John Evans (London: Thomas Hurst [et al.]; printed by Albion Press 1804), xlvi, 100pp., ill. [front. and engravings - available at Internet Archive - online.]

- The Plays of Oliver Goldsmith, together with The vicar of Wakefield, ed., with glossarial index and notes, by C. E. Doble, M.A., asst. by George Ostler (London & NY: H. Frowde 1909), viii, 520pp.

|

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

Modern Editions, William Henry Hudson, intro. & annot., Vicar of Wakefield [Heath’s English Classics] (Boston: D.C. Heath & Co. [1920]), xxxv, [1], 264, [2]pp, pls., port.; R. S. Crane, ed., New Essays by Oliver Goldsmith (Chicago UP 1927); Katherine Balderston, ed., The Collected etters of Oliver Goldsmith (Cambridge UP 1928); Arthur Friedman, ed., The Collected Works of Oliver Goldsmith, 5 vols. (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1966); The Deserted Village by [OG] with a note on the author and a summary of his life by Desmond Egan (Curragh: Goldsmith Press 1978), 44pp.; Tom Davis, ed., She Stoops to Conquer [New Mermaid Ser.] (London: A & C. Black 1996) [8th edn.]; The Deserted Village, ill. Blaise Drummond (Oldcastle: Gallery Press [2002]), 58pp.

[ top ]

|

|

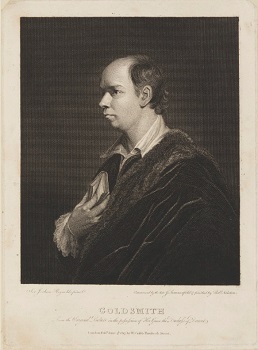

| Summerfield (after Reynolds) | Foley’s Goldsmith (TCD) |

|

See also James Boswell, Life of Johnson [1791], G. B. Hill; revised L. C. Powell, 6 vols. (OUP 1939-50); Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies (1821), Vol. II, p.181-97; J. J. Kelly, The Early Haunts of Oliver Goldsmith (q.d.), and C. A. Moore, Backgrounds of English Literature 1700-1776 (Minnesota UP 1953); |

See The New Cambridge Bibliography of English ..., Volume 2: 1660-1800, by George Watson (Cambridge UP 1971) - Essays and Pamphleteers, Goldsmith, pp.1191-1210ff. [Google Books online; accessed 08.03.2011]. |

[ top ]

See separate file [infra].

See separate file [infra].

[ top ]

|

Dictionary of National Biography, cites Goldsmith under Sir William Petty [Lord Landowne and 2nd Earl Shelburne] (1737-1805), known as “Malagrida” by his enemies for his lack of sincerity, to whom Goldsmith addressed the unfortunate remark, ‘Do you know that I never could conceive the reason why they call you Malagrida, for Malagrida was [very] very good sort of man’. DNB also lists Robert Hasell Newell (1778-1852), amateur artist and author, ed. Cambridge, who illustrated the Goldsmith edn. of 1811-20.

Charles A. Read, The Cabinet of Irish Literature [1876-78]; There is a very circumstantial biographical notice in Cabinet of Irish Literature, ed. Charles Read (1876; Vol. 1), citing inter al. Prior’s biography which ‘did little to remove the impression of the author of The Traveller as a kind of inspired idiot’; also cites an edn. of The Vicar of Wakefield of 1843 with 32 ills. by William Mulready; edition of Poetical Works, ed. Rev. R. H. Newell [see DNB supra], in which the locality of The Deserted Village is traced, and ills. by seven engraving on the spot by Mr Aitkin (1811); also Prior’s edn. of the Works (1836), throwing the ‘legion’ editions before it ‘into the shade’; Cunningham Murray’s edn. of 1854 forms basis of Murray’s British Classics; lives by Washington Irving and Foster (viz, Life and Adventures).

Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (1904), Vol., IV, quotes inter alia: ‘What we say of a thing which is just come in fashion,/And that which we do with the dead,/Is the name of the honestest man in creation;/What more of a man can be said?’ (Goldsmith, in a verse-charade on his employer John Newbury; cited in evidence that he was not exploited (p.1299).

D. J. O’Donoghue, The Poets of Ireland: A Biographical Dictionary, (Dublin: Hodges Figgis & Co 1912); ‘Said to have been born at Pallas, near Ballymahon, Co. Longford, but more probably born in Co. Roscommon; ed. village schools, Elphin, Athlone, and Edgeworthstown; TCD; Edinburgh; Leyden.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1: selects from The Traveller, or a Prospect of Society (London 1764) [433-35]; The Deserted Village [447-53]; She Stoops to Conquer; or, Mistakes of a Night (London 1773) [570-603]; Miscellaneous Writings [658-81]: An Enquiry into the Present State of Polite Learning in Europe (Lon 1759) [ 660-62]; The Bee (Lon 1759) [662-64]; A Description of the Manner and Customs of the Native Irish. In a Letter from An English Gentleman [evid. of Goldsmith authorship, see Friedman, ed., Works, III, p.24] [664-67]; The History of Carolan, the Last Irish Bard [667-68]; A Comparative View of Races and Nations [668-71]; The Citizen of the World; or, Letters from a Chinese Philsopher, Residing in London, to his Friends in the East (London 1762) [671-79]; A General History of the World [674-79]; An Essay on the Theatre [679-81]; The Vicar of Wakefield (Salisbury 1766); 746-51]; REMS at xxi, xxiii; 503 [exploitation of own personality, as in Good-natur’d Man, characteristic of Anglo-Irish playwrights]; 504-505 [playing with national characters, Tony Lumpkin, in answer to question, ‘Are they Londoners’, says, ‘I believe they may. They look woundily like Frenchmen’]; 506 [Goldsmith’s essay on theatre makes clear his objections to weeping comedy; constrained by normal tastes, tempering Goldsmith’s love of farcical or low scenes]; 546 [gathered with Murphy and Sheridan as opposed to sentimental comedy]; 566 [Kelly did not go for amusing mistakes, like Goldsmith]; 647 [O’Keeffe creates little farce in Tony Lumpkin in Town by sidestepping the stage-Irishman in depicting Lumpkin’s lively boorishness]; 654 [She Stoops to Conquer, Dublin 1st ed. 1773]; BIOG & COMM, [492 see supra]; 656 [as supra; ‘Oliver Goldsmith, Miscellaneous. Writings’, ed. essay, pp.658-61 [see infra]; 681 [add. bibl., as above]; 686 [Goldsmith as model for Anglo-Irish novelists]; 856 [the idea of citizenship was universal; man could become, in Goldsmith’s famous (if not original) phrase, a citizen of the world; eds., Deane, Carpenter, McCormack]; 962 [on Carolan]; 1000 [Thomas Campbell known to Goldsmith]; 1010 [Campbell wrote part of the memoir of Goldsmith in Percy’s work (1801)]; 1208n [Latin version of Johnson’s epitaph, cited by Isaac Butt, in Past and Present State of Literature in Ireland (1837), as supra].

Arthur Quiller Couch, ed., Oxford Book of English Verse, 1250-1918 (new ed. 1929), item 559; Justin McCarthy, ed., Irish Literature (1904), gives copious extracts incl. ‘The Haunch of Venison’.

Shell Guide (1967), b. Pallas, a little to the east of Ballymahon, 10 Nov. 1728; his father got the living of Kilkenny West in 1730, and moved to Lissoy, or ‘Sweet Auburn’, 5 miles south-west of Ballymahon in Westmeath, where the ruins of his house are still to be seen; ed. in village by Thomas Byrne, schoolmaster, who spent some years in Peninsular Wars; afterwards went to Athlone to prepare for university, passing later to Mostrim. Connected places, Ardagh, Elphin, Forgney, and Kilkenny West.

British Library (1957 Cat.) lists under MISCELLANEOUS WORKS: The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Containing all his essays and poems (London: W. Griffin 1775), iv, [9-]200pp., 8o; another edn. (London: W. Griffin 1778), vi, 225pp., 12o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin 1780; 1782; 1784; 1786), vi, 225pp., 8o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin 1786), 238pp., 12o; another edn. (London: W. Osborne & T. Griffin; Gainsbro’: H. Mozley 1789), 238pp.,. 12o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Consisting of his essays, poems, plays [&c.], 2 vols. (Edinburgh, Perth: R. Morison & Sons 1791), 12o; The miscellaneous works, 4 vols. (Edinburgh: Geo. Mudie 1792), 12o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith; now first uniformly collected, 7 vols. (Perth: R. Morison & Son; Edinburgh: A. Guthrie 1792) plates, port. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Containing all his essays and poems; with an account of the life and writings of the author. A new and correct edition (London: J. Deighton 1793), xli, 288pp., 12o; another edn. (Glasgow: J. & M. Robertson, et al. 1795), another edn. (Boston [Mass.]: Thomas & Andrews, 1795), 237pp. 12o; [Samuel Rose, ed.,] The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. A new edition, To which is prefixed, some account of his life and writings [by Thomas Percy, Bishop of Dromore], 4 vols. (London: J. Johnson, et al. 1801; 1806), pls., port. 8o. . 4 vol.: plates; port. 8o; another edn. (London: W. Otridge & Son, 1812); another edn. (Glasgow: R. Chapman 1816); another edn. (London: F. C. & J. Rivington, et al. 1820); another edn., 6 vols. (London: Samuel Richards 1823), plates; port. 12o; Washington Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings. A new edition. 4 vols. (Paris: A. & W. Galignani; Jules Didot 1825), plate, port., 8o; Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings, stereotyped from the Paris edition (Philadelphia: J. Crissy; Desilver, Thomas & Co. 1836), 527pp., plate; port. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, with an account of his life and writings, 4 vols. (Paris: Baudry’s European Library, &c. 1837), plate; port., 8o; James Prior, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. Including a variety of pieces now first collected (London: John Murray 1837), 8o; Irving, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. To which is prefixed some account of his life and writings [extracted from the edition of 1823]; another edn. (Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson 1840), xxii, 458pp., plate, port., 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. With a brief memoir of the author [&c.] (London: Andrew Moffat; Glasgow: D. A. Borrenstein 1841), xii, 308pp.; illus. 8o; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, M.B. To which is prefixed some account of his life and writings. A new edition, [etc.] (Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson 1843) xxii, 458pp., plate, port., 8o; James Prior, ed., The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith, including a variety of pieces now first collected, 4 vols. (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott & Co. 1866), ill. plates.; The Miscellaneous Works of Oliver Goldsmith. With biographical introduction by Professor Masson [The Globe edition] (London & NY: Macmillan & Co. 1869 [1868]; 1871), lx, 695pp., 18cm.

Booksellers

Eric Stevens Books (Cat. 166) lists The Vicar of Wakefield (1766), rep. (1843), being 1st edn. with William Mulready ills.; another edn. (1855); another, intro. George Saintsbury (1926), with 25 col. ills. by Rowlandson ; also Le Vicaire de Wakefield, trad. par B.-H Gausseron, Paris, Quantin ca.1890, Royal 8vo, 297pp, ill. Poincon, hand-coloureds. Note: 1855 edition with Muready is available at Internet Archive - online.

Emerald Isle Books (Cat. 1995) lists The Vicar of Wakefield (1843), 1st edn. with Mulready ills.; others edns. 1855; another edn. with intro. by George Saintsbury and Rowlandson col. ills, 1926. Also lists The Vicar of Wakefield (London: C. Ware 1777), 2 vols in 1 £75].

Hyland Books (Cat. 235) lists Lives of Dr. Parnell and Lord Bolingbroke, with “The Bee” (Belfast 1818), vi, 243pp., 6°.

Berg Collection (NYPL), holds edn. of The Haunch of Venison (London: Kearsly 1776), book pl. of Austin Dobson; also with ‘The Tears of Genius; occasiond by the death of Dr. Goldsmith, by Courtney Melmoth [pseud.]’ (London: for T. Becket 1774).

Libraries

Marsh’s Library holds The Monthly Review, Vol. XVI (London: for R. Griffiths 1757), 8o.

TCD Long Room (Spring 1978) cites The Haunch of Venison, a poetical epistle to Lord Clare (London: G. Kearsly & J. Ridley 1776), 4o.

Belfast Public Library holds 20 titles incl. Lives of Dr. Parnell and Lord Bolingbroke, with The Bee; var. Histories; Prospect of Society (1902); Works and Poems; and biographies by Stephen Gwynn (1935); T. P. C. Kirkpatrick (n.d.); W. Freeman (1951). MORRIS holds Dalziel’s Illustrated Goldsmith and a sketch of the life ... by H. M. Ducklen (Ward & Lock, 1865); Letters of a Citizen of the World, the Traveller, The Deserted Village (c.1930); The Vicar of Wakefield (c.1935).

[ top ]

Notes

Patrick Delany: for a possible source of the plot of The Good-Natured Man, see remarks of Patrick Delany: “The Duty of Paying Debts”: ‘A good-natured villain will surfeit a sot and gorge a glutton, nay, will glut his horses and his hounds with that food for which the vendors are one day to starve to death in a dungeon; a good-natured monster will be gay in the spoils of widows and orphans. / Good-nature separated from virtue is absolutely the worst quality and character in life; at least, if this be good-nature, to feed a dog, and to murder a man. And therefore, if you have any pretence to good-nature, pay your debts and in so doing clothe those poor families that are no in rags for your finery ...’.]

Lady Morgan worked as a governess for a Mrs Margaret Featherstone, wife of James Featherstone, High Sherriff of Westmeath, at their home Bracklin Castle; Mrs Featherstone’s mother was a former beauty of the court of Lord Chesterfield in Dublin, Lady Steele of Dominick St. According to Mary Campbell, ‘Oliver Goldsmith, her father’s cousin, also came from this part of Ireland, and describes the landscape in “The Deserted Village”. Here he also set his most famous play, for it was a real life Squire Featherstone upon whom he based the theatrical Squire Hardcastle, in She Stoops to Conquer.’

William Carleton cites a line from Deserted Village (‘I dragged at each remove a lengthening chain’, in the Introduction to the 1843 edn. of Traits and Stories (p.xiv), descriptive of his setting out alone as a ‘poor scholar’ for Munster.

Sir John Gilbert, History of Dublin (1865), Vol. I: ‘A practical joke played by Kelly upon Oliver Goldsmith, who induced him from his representation to take the house of Sir Ralph Fetherstone at Ardagh for an inn, is believe to have suggested the plot of She Stoops to Conquer.’ (p.87). Note, the Oxford Companion to English Literature (ed. Drabble) notes that the mistaking of a private residence for inn was testified by Goldsmith’s sister Mrs Hodson.

W. B. Yeats placed Goldsmith in company with Burke, Berkeley, and Grattan, all in his conception Whigs though they did not know it: ‘Oliver Goldsmith sang what he had seen,/Roads full of beggars, cattle in the fields,/But never saw the trefoil stained with blood,/The avenging leaf those fields raised up against it.’ (“The Seven Sages”, 1932). Note that The Royal Theatre, Stockholm, played She Stoops to Conquer with Yeats’s Cathleen ni Houlihan, at the time when the poet received his Nobel Prize, Dec. 1923.

James Joyce: Goldsmith’s “Retaliation” was taught at Belvedere to James Joyce, giving rise to a pastiche-poem on a schoolmate, G. O’Donnell; Joyce also praised Goldsmith for his personal qualities (‘unassuming’), as retaled in Padraic Colum’s memoir in Ulick O’Connor, ed., The Joyce that We Knew (Cork: Mercier 1967), p.81f.

Newbery’s profit: A History of England in a Series of Letters from a Nobleman to his Son (1764) was a popular success in its two pocket-size volumes, issued by Newbury [vars. Newbury; Newberry].

The Gaiety Theatre (Dublin) opened its doors for the first time in Nov 1871 with a performance of Goldsmith’s comedy She Stoops to Conquer.

Ill Fares the Land: The book of that title by Tony Judt (NY: Penguin 2010) is an indictment of corporate greed in America, resulting in a revisitation of - in Galbraith’s phrase - private wealth and public squalor. Judt writes: ‘Something is profoundly wrong with the way we live today. For thirty years we have made a virtue out of the pursuit of material self-interest: indeed, this very pursuit now constitutes whatever remains of our sense of collective purpose. We know what things cost but have no idea what they are worth. We no longer ask of a judicial ruling or a legislative act: is it good? Is it fair? Is it just? Is it right? Will it help bring about a better society or a better world? Those used to be the political questions, even if they invited no easy answers. We must learn once again to pose them. [...]’ (Extract in New York Times, 17 March 2010- online.) Reviewer Josef Joffe calls Judt’s book an example of the ‘classic fallacy of the liberal-left intelligentsia [...] the “Doctor State Syndrome”’ (review of same in NYT, 2 May 2010 [online: both accessed 11.09.2010].

Portraits: statue in bronze by J. H. Foley, 1861 [var 1864 CAB], at College Green (TCD); also, portrait in oil by Reynolds, of which there is a copy in Nat. Gallery of Ireland. (See Anne Crookshank, ed., Irish Portrait Exhibition [Catalogue] (Ulster Mus. 1965). See also an engraving after Wheatley, 1791, of a moment from Act V, sc. 3 of She Stoops to Conquer (rep. in Brian de Breffny, Ireland: A Cultural Encyclopaedia, London: Thames & Hudson, p.238.)

[ top ]