Life

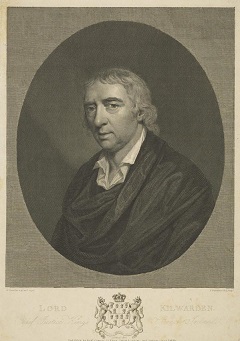

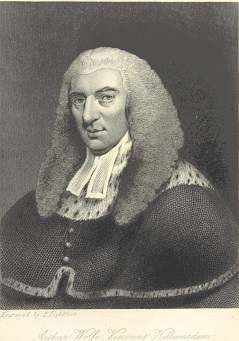

1739-1803 [sometimes Woulfe]; b. Forenaughts, Co. Kildare; 1st Viscount Kilwarden, Lord Chief Justice of Ireland; ed. TCD; bar, 1766; KC, 1778; MP for Coleraine, 1783; Sol.-Gen., 1787; MP Jamestown, 1790; unsuccessful Crown Attorney in the trial of William Drennan, 1792; removed from office by Fitzwilliam, 1795; MP Dublin, 1798; Chief Justice and Baron Kilwarden of Newlands, 1798; supported the Union; created viscount, 1800; dragged from carriage by mob, and most prominent victim of the Emmet Rising, 1803;

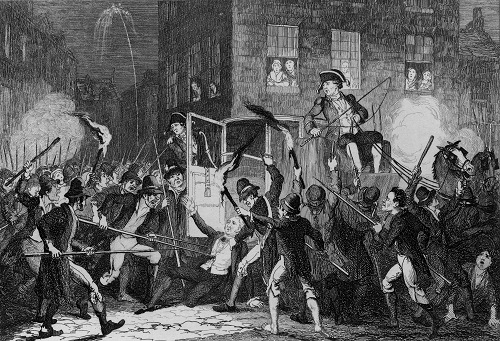

his death is the subject of a celebrated engraving by George Cruikshank in [W. H. Maxwell, The Irish Rebellion, 1845], characterising the Irish rebels as a bestial mob; there is also a footnote account of Kilwarden’s death in C. R. Maturin’s Melmoth the Wanderer (1820; Chap. XII); Wolfe lived in Newlands House, Newlands Cross, Dublin - subsequently occupied by George Ponsonby (Lord Chief Justice 1806-07), later the seat of the White Quaker’s, later used a golf-club and finally demolished in 1981. ODNB DIB DUB FDA2

|

|

|

| The Murder of Lord Kilwarden in 1803 (George Cruikshank, in Maxwell, 1845) | ||

|

||||||||||||||||

John O’Donovan, ‘The Irish Judiciary in the 18th- and 19th-Centuries’, in Éire-Ireland, 6, 4 (Winter 1971), pp.17-22, ‘Goodnatured boobies like Robert Day and Arthur Wolfe Viscount Kilwarden (who it has been hinted was the illegitimate father of Wolfe Tone) enjoyed a certain popularity and public esteem. Kilwarden’s measure as Chief Justice of the King’s Bench may be taken from his handling of a case of alleged rape in the archbishop’s summer palace at Tallaght. He has his own summer residence a couple of miles down the road from the palace and he spent an extraordinary amount of time during the case chatting up the plaintiff about fields and cottages in the neighbourhood, just like any village gossip. It was left to his venerable [21] puisne, who was sitting with him, to ask the plaintiff relevant questions about the how and when, and in particular about why she had stayed in a room with the rapist for a few days without making any attempt to draw the attention of the people who were passing by the door. When the puisne had satisfied himself on these points Kilwarden led the plaintiff back to the chat about the fields and the cottages.’ (p.22).

| Kinsella, “1803” - After the engraving by George Cruickshank |

|

|

Conor Cruise O’Brien, The Great Melody (1992), Fitzwilliam arrives in Dublin, 4 Jan. 1795, and takes on the Junto of senior officials who dominated the viceregalty of his predecessor Lord Westmoreland; he removes from office John Beresford, First Commissioner of the Revenue, and Arthur Wolfe, Attorney General. [c.p.522]. [ top ]

Kevin Whelan, ‘Origins of the Orange Order’, Bullán: An Irish Studies Journal, 2, 2 (Spring/Summer 1996), notes that W. Richardson, one of the principles of the yeoman movement, sent Kilwarden a letter dated 2 May 1803, dealing with the polarisation of parties in Northern Ireland into Orange and Papists by 1797. (pp.25-26.)

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography cites one Lyde Browne (d.1803; whose f. is also listed); entered army, 1777; lieutenant-col., 1800; shot by Emmet’s mob in Dublin, 1803.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, incl. comments by W. J. McCormack, ed., ‘Irish Gothic and After’ [sect.], in which Maturin’s account of the death of Wolfe [Lord Kilwarden] in the rising of 1803, taken from a footnote of Melmoth the Wanderer, is given, thus: ‘In the year 1803, when Emmett’s [sic] insurrection broke out in Dublin - (the fact from which this account is drawn was related to me by an eye witness) - Lord Kilwarden, in passing through Thomas Street, was dragged from his carriage, and murdered in the most horrid manner. Pike after pike was thrust through his body, till at last he was nailed to a door, and called out to his murderers to “put him out of his pain”. At this moment, a shoemaker, who lodged in the garret of an opposite house, was drawn to the window by the horrible cries he heard. He stood at the window, gasping with horror, his wife attempting vainly to drag him away. He saw the last blow struck - he heard the last groan uttered, as the sufferer cried, “put me out of pain”, while sixty pikes were thrusting at him. The man stood at his window as if nailed to it; and when dragged from it, became - an idiot for life.’ (Bibl., Douglas Grau, ed., Melmoth the Wanderer: A Tale, London: OUP 1968, p.257n.; FDA2, p.835.

[ top ]

Notes

Kilwarden in court: Edward Hay recounts, in his History of the Insurrection of County Wexford, 1798 (1803), that Kilwarden released a child called Master Letts - a relative of Bagnal Harvey - who was held prisoner in Wexford as an insurgent and afterwards transferred by habeas corpus to his court in Dublin: ‘In January 1799. a writ of habeas corpus was obtained, and master Lett was brought by the sub-sheriff of the county of Wexford, from Wexford gaol to the court of king’s-bench, in Dublin, and on enquiry for the prisoner he was held up on a man’s arm, to the utter astonishment of Lord Kilwarden, and thus was prejudice scouted out of the court by his liberation. This, I believe, unexampled case, took place in the presence of a [f]ull attendance of the gentlemen of the bar, who had crowded to see such a phenomenon, as from the child’s appearance it was thought he wanted the superintendance of a nurse more than a gaoler.’ (p.xxi; see further under Hay, q.v.)

Portraits: Arthur Wolfe is included in an engraving of House of Commons of 1790, now preserved in Bank of Ireland (College Green) [No. 47 in key] but his monument is undoubtedly the scene of the assassination by the mob as rendered by George Cruikshank in a plate illustrating W. H. Maxwell’s The Irish Rebellion (1845).

[ top ]