| 1581-1656 [freq. Usher. Archbishop of Armagh]; b. 4 Jan., Nicholas St., Dublin, son of Dublin lawyer and member of familay with many Catholic members incl. his uncle Richard Stanyhurst, a recusant; ed. school of two Scottish agents of James VI, seeking to establish a party in Ireland; entered TCD at it foundation, the charter having been secured by his uncle Henry Ussher [q.v.; archbishop of Armagh]; schol., 1594; grad. 1600; fellow, 1599-1605; lay preacher at Christ Church, Dublin; MA and ord. 1601; sent to England to buy books for TCD, 1602; Chancellor of St. Patrick’s, and rector of Finglas, 1605; professor of theol. controversies, 1607-21; rector of Assey, 1611-26; published Gravissimae Questionis de Christianarum Ecclesiarum [ …] Historica Explicatio (1613), a history of the Western Church extending the narraive in Jewel’s Apology for the Church of England from the third to the middle of the thirteenth century; DD, 1614; prepared Calvinist convocation articles of Church of Ireland with others, 1615; appt. Vice-Chancellor of TCD, 1617; appt. rector of Trim, 1620; |

|

||

| elev. to Bishop of Meath, 1621, when the Book of Kells was in his possession and care in his house in Drogheda, having previously been held by Richard Plunkett, last abbot of the monastery, and thereafter by his kinsman Gerald Plunkett in Dublin; issued Discourse of the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish and the British, first pub. as an appendix to Christopher Sibthorp’s A Friendly Advertisement to the Pretended Catholics of Ireland (Dublin 1622) and arguing for the continuity of the British and Irish Churches in opposition to Rome; later published in fuller edition of 1631 and primarily aimed at an Old English [Norman-descent] audience; studied in England, 1623-26, bringing the Book of Kells with him; appt. Archbishop of Armagh, 1625; obstructed progress on Bedell’s Bible and discountenanced idea of using Irish in the religious service, 1629; defeated efforts to make Irish doctrine conform exactly with English; incorporated DD, Oxon., 1626; defended penal laws, 1626-27; corresponded with Laud advertising the prestige of the Irish primacy in comparison with that of Canterbury as descending from St. Patrick, 1628-40; attacked Philip O’Sullivan Beare and was himself the object of an attack in the appendix of Decas Patritiana (1629) where he is called “Archicornigeromastix”; | |||

| issued Discourse on the Religion Antiently Professed [...] (1631) [as above]; issued Britannicarum ecclesiarum antiquitates (Dublin 1639) [var. Primordia] on a reading of the Patrician narratives in the Book of Armagh [but see note on Antoninus, infra]; accepted on instructions of Strafford the English 39 Articles but rejected the English canons of 1604 in favour of Irish canons, 1634; crushed pretensions of Archbishop Bulkeley of Dublin to Irish primacy in special hearing before Lord Lieutenant, 1634; pressed for equality of Irish primacy at Armagh with that at Canterbury as direct successor of St. Patrick, 1634; left Ireland 1640; counselled Charles I against the execution of Strafford; drafted a scheme of modified episcopacy acceptable to puritans, published without his permission, 1641; | |||

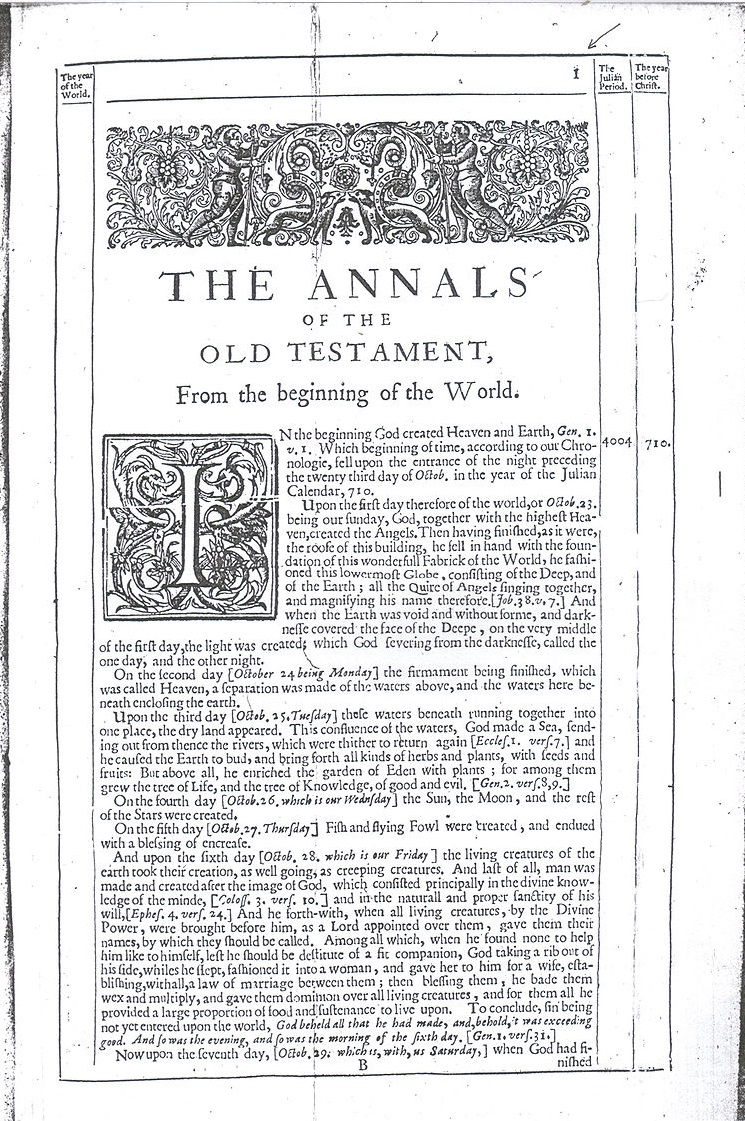

| held bishopric of Carlisle [in commendam], Feb. 1642-Autumn 1649; moved to Oxford, 1642; voted pension of Westminster, Sept. 1643, not being paid until in Dec. 1647; objected to Westminster Assembly of divines, 1643; took refuge in Wales, 1645; guest of Countess of Peterborough, at Reigate, Surrey, 1646; conferred with Charles I in Isle of Wight on abortive negotiations with Parliament on question of episcopacy; acted as preacher at Lincoln’s Inns, 1649; offered a pension by Richelieu, c.1649; issued Chronology or Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti, 2 vols. (1650-54), in which he calculated the age of the world, placing the creation at 23rd Oct. 4004 bc [Julian calendar 710] - a chronology long after accepted and printed by an unknown authority in the Authorised Version of the Bible; issued De Graeca LXX Interpretum Versione Syntagma (1655), his last work; d. 20 [err. 21 March DIB] at Lady Petersborough’s house, Reigate, Surrey; buried in state in Westminster, 17 April, with permission of Oliver Cromwell; | |||

| Posthum: his library of 10,000 vols. was bought for £2,000 in 1658, and placed in TCD by Charles II at the Restoration, 1661; nephew of Richard Stanihurst [q.v.] - who wrote contra his anti-Catholic opinions - and son-in-law of Luke Challoner; Ussher was considered implacably opposed Catholicism in religion but seen to be kindly to Catholic friends; he believed that the influence of Rome was weak in Gaelic Ireland, and that early Irish Church was closer to Protestantism than to Roman Catholicism, and was so-quoted in Edmund Burke’s Tracts relative to the Laws Against Popery (1763) ; Charles Gavan Duffy proposed that his remains be brought back to Ireland, in Irish Statesman (4 Sept. 1926); there is a portrait of Ussher doubtfully attrib. to Sir Peter Lely; astronomists marked 25 Oct. 1996 as the day on which the world would end according to his forecast; his chaplain Richard Parr wrote "The Life of James Ussher", prefixed to the edition of Usher’s Letters (London 1686). RR CAB ODNB PI DIB DIW OCEL FDA OCIL | |||

[ top ]

Works| Chief writings |

|

| Collected works |

|

| Letters |

|

|

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Related texts incl. Richardi Stanihursti [Richard Stanihurst], Brevis praemunitio pro futura concertatione cum Jacob Usserio qui in sua historica explicatione conatur probare Pontificem Romanum ... verum & germanum esse Antichristum (Duaci [Douai]: ex typographia Baltazaris Belleri 1615), 39pp. |

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

An Answer to a Challenge made by a Iesvite in Ireland wherein the Iudgement of Antiquity in the points questioned is truly delivered, and the Noveltie of the now Romism doctrine plainly discovered, by Iames Ussher Archbishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland wherevnto Certain other treatises of the same author are adjoyned, the titles whereof in the [n]ext leafe are more particularly specified (London, printed for RI the Partners of the Irish Stocke. 1631), 583pp.. Appendix includes 1.] An Answer to a challenge made by a Iesuite in Ireland, first published in the yeare, 1624, and since revised and augmented. 2.] A sermon preached before the house of commons, 18th Feb. 1620. 3.] A brief declaration of the Universality of the Church of Christ, and the Unitie of the Catholic Faith professed therein, delivered in a sermon before the Kings majestie, the 20th of June 1624. 4.] A discourse of the religion anciently professed by the Irish and the British, first set forth in the yeare 1622 and now digested in some better forme, and further enlarged. 5.] A speech delivered in the Castle-Chamber at Dublin, the 22th November 1622 concerning the Oath of Supremacy [called rare by CAB]. Includes chronological list of authors cited from Nicodemus to Erasmus. Top of page titles in the last section include Of Prayer to Saints, Of Images, Of Free-will, &c.Jacobi Usserii Armachani Annales Veteris et Novi Testamenti: a prima mundi origine deducti usque ad extremum Templi et Reipublicæ Judaicæ excidium. Cum duobus indicibus quorum primus est historicus, secundus vero geographicus qui nunc primùm prodit in lucem / Cura & studio A. Lubin geogr. regii. Accedunt eiusdem I. Vsserii tractatus duo. I. Chronologia sacra Veteris Testamenti. II. Dissertatio de Macedonum et Asianorum anno solari (Lutetiæ Parisiorum: Sumptibus Lud. Billaine & Joannis Du Puis, MDCLXXIII [1673]), [102], 688, [4], 126 pages, 1 unnumbered leaf of plates, folio [36cm]. (See COPAC - online.)

Richard Parr, The Life of the Most Reverend Father in God, James Usher, late Lord Arch-Bishop of Armagh, primate and metropolitan of all Ireland: With a collection of three hundred letters, between the said Lord Primate and most of the eminentest persons for piety and learning in his time, both in England and beyond the seas. / Collected and published from original copies under their own hands, by Richard Parr, D.D. his lordships chaplain, at the time of his Death, with whom the care of all his papers were intrusted by his lordship [in caps]. (London: Printed for Nathanael Ranew, at the Kings-Arms in St. Pauls Church-Yard, 1686), [8], 103, [5], 33, [19], 92, 301-624pp., 28, [2] pages, 1 unnum. lf. of pls: port.; 32 cm (fol.) [See further details in COPAC - online; accessed 19.01.2024.]

Note: Richard Parr is the subject of an entry in Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica .. Irish Worthies, Vol. II (London & Dublin 1821) as attached.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

| [ top ] |

|

| [ top ] |

ON THE DEMPSTER CONTROVERSY - see Joep Leerssen, Mere Irish and Fíor Ghael, 2nd ed. (Cork UP 1996 [rep. edn.]), pp.263-77; Bernadette Cunningham & Raymond Gillespie, ‘“The Most Adaptable of Saints”: The Cult of St. Patrick in the Seventeenth Century’, in Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 49 (1995), pp.92-93; John McCaffrey, ‘“God bless Your Free Church of Ireland”: Wentworth, Laud, Bramhall and the Irish Convocation of 1634’, in J. F. Merritt, ed., The Political World of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford (Cambridge 1996), pp.187-208; Joep Leerssen, ‘Archbishop Ussher and the Gaelic Past’, in Studia Hibernica, Vols. 22-23 (1982-23), pp.50-58; William Monck Mason, The Catholic Religion of St. Patrick and St. Columbkill (Dublin 1822); Nelson McCausland, Patrick Apostle of Ulster: A Protestant View of St. Patrick (Belfast 1997). Also William O’Sullivan [q. title], Irish Historical Studies, XVI, No. 62 (Sept. 1968), pp.215-19.

Bibliographical details

R. Buick Knox, James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh (Cardiff: Wales UP 1967), includes bibliography: Hugh Jackson Lawlor, ‘Primate Ussher’s Library before 1641’, PRIA, 3rd ser. 6 (1900-02), pp.216-64; T. C. Barnard, ‘The Purchase of Archbishop Ussher’s Library in 1657’, Longroom, 2 (1970), pp.9-14; Seán O’Donnell, ‘Early Irish Scientists’, Eire-Ireland, Vol. 11, no.1 (1979); also New History of Ireland, III; Aubrey Gwynn, ‘Archbishop Ussher and Fr Brendan O’Connor’, in Father Luke Wadding, ed., Franciscan Fathers, Killiney (Dublin: Clonmore & Reynolds 1957), pp.263-75; ‘Why the World was Created in 4004 BC, Archbishop Ussher and Biblical Chronology’, in Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 67 (Spring 1985), pp.575-608. See also Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies (1821), Vol. II, pp.610-15; also James & Freeman Wills, The Irish Nation; see Irish Book Lover, Vol. 2.

[ top ]

Older commentators

Edmund Burke, Tracts relative to the Laws Against Popery (1763): ‘[...] However, before we pass from this point concerning possession, it will be a relaxation of the mind not wholly foreign to our purpose to take a short review of the extraordinary policy which has been held with regard to religion in that kingdom, from the time our ancestors took possession of it. The most able antiquaries are of opinion, and Archbishop Usher (whom I reckon amongst the first of them) has, I think, shown that a religion, not very remote from the present Protestant persuasion, was that of the Irish before the union of that kingdom to the Crown of England. If this was not directly the fact, this at least seems very probable, that Papal authority was much lower in Ireland than in other countries. This union was made under the [48] authority of an arbitrary grant of Pope Adrian, in order that the Church of Ireland should be reduced to the same servitude with those that were nearer to his See. It is not very wonderful that an ambitious monarch should make use of any pretence in his way to so considerable an object. What is extraordinary is, that for a very long time - even quite down to the Reformation - and in their most solemn acts, the kings of England founded their title wholly on this grant. They called for obedience from the people of Ireland, not on principles of subjection, but as vassals and mean lords between them and the Popes; and they omitted no measure of force or policy to establish that papal authority with all the distinguishing articles of religion connected with it, and to make it take deep root in the minds of the people.’ (Matthew Arnold, ed., Letters, Speeches and Tracts, on Irish Affairs, London: Macmillan 1881, and Do., as Irish Affairs, with a new introduction by Conor Cruise O’Brien [rep. of 1881 Edn.], London: Cresset Press 1988, pp.48-29.) [The 1881 edition is available at Internet Archive - online.]

George Saintsbury (English Literature, 1898), more a writer than a preacher, the most erudite of an erudite time, and one of the most voluminous authors of a time when most authors were voluminous ... escapes the blame not quite justly passed on Andrewes by never attempting flights or rhetoric at all ... did not wish his sermons to be published ... chronological works mainly in Latin ... in English wrote chiefly on Celtic Antiquities, especially ecclesiastical ... Protestant-Papist controversy, divine right (etc.) ... his style largely conditioned by his method of argument which consists ... in appeals to authority and citations from inexhaustible store of his vast reading ... always plain an clear ... [no] superfluity of ornament; b. Dublin 1581, nephew of Stanyhurst, the eccentric translator of Virgil, Prof. Divinity 1607; Bishop of Meath 1620, Archb. of Armagh, 1625; preacher at Lincoln Inn during the Rebellion; steadily a Royalist, not molested by Parliament; d. Reigate in 1656. (1922 ed., p. 384).

[ top ]

Modern critics

Prof. James O’Meara, Eriugena (Mercier 1969): ‘Bishop Ussher referred to him as Scotus Erigena in his Veterum epistolarum Hibernicarum sylloge (Dublin 1632) and to this tautology subsequent errors are chiefly due.’ (p. vii.)

Colin Renfrew, Before Civilization: The Radio Carbon Revolution and Prehistoric Europe (Penguin 1972): ‘The European solution to this yawning void in human understanding [of the chronology of pre-historic time] was, until the nineteenth century, just the same as that of most earlier culture: to rely on myth. The ancient Egyptians, the Maya, the Classical Greeks, all had their version of the beginning of things, and the Bible, likewise supplied a circumstantial account of the ‘first morning of the first day’. The long genealogies of the sons of Adam, given in the Book of Genesis, permitted - when taken literally in the fundamentalist way - a reckoning in terms of generations back from the time of Moses to the Creation. The seventeenth-century Archbishop Ussher set the date of the Creation at 4004 b.c., a later scholar fixing it with remarkable on October 23rd of that year, at nine o’clock in the morning. This convenient fixed point, printed in the margin of the Authorised Version of the Bible, gave scholars an inflexible boundary for early human activity., a starting point for prehistory and the world. / Nor was this belief restricted to the credulous or excessively devout. No less a thinker than Sir Isaac Newton [fig. here from Auth. Vers.; 22] accepted it implicitly, and in his detailed study of the whole question of dating. The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, took the ancient Egyptians severely to task, since they they had set the origins of their monarchy before 5000 b.c., and “anciently boasted of a very great Empire under their Kings […] reaching eastward to the Indies, and westward to the Atlantic Ocean; and out of vanity have made this monarchy some thousands of years older than the world”. 4 This criticism was meant literally: for an educated man in the seventeenth or even the eighteenth century, any suggestion that the human past extended back further than 6000 years was a vain and foolish speculation. (pp.22-23.)

W. B. Stanford, Ireland and the Classical Tradition (IAP 1976; 1984), James Ussher, [Luke] Chaloner’s younger contemporary [as Fellow at TCD] and a richer man, had a much larger classical collection, though his own chief interests were in ecclesiastical history. Note, TCD has MS catalogues of Chaloner’s and Ussher’s books, both part of the collection. Further: James Ussher’s Epistle concerning the Religion of the Ancient Irish (1622), among the first uses of Greek type by Dublin printers. Further: James Ussher, produced a treatise on history and geography of Asia in 1643; not primarily interested in what he called ‘heathen story’; only minor works in his large corpus of mainly ecclesiastical history. [144] Bibl.: Stanford’s notes refer uniquely to R. Buick Knox, James Ussher, Archb. of Armagh (Cardiff 1967).

Joseph Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fíor Ghael (Amsterdam 1986), Ussher called Thomas Dempster in Greek ‘a thief of saints’. Further, ‘Philip O’Sullevan Beare, his Decas Patritiana (1629) in 10 books on St. Patrick, with an appendix attacking Bishop Ussher strongly ad hominem under the name as “Archicornigeromastix”’. Further, ‘Thomas Strange wrote in Mar 1696 to Luke Wadding from the Franciscan house in Dublin where Michael Clery spent time copying, reporting that Ussher had offered to help the Gaelic antiquarians to the extent of lending his library; and there is evidence that such bi-partisan contacts continued even after the 1641 Rebellion.’ See R. B. Knox, James Ussher, Archbishop of Armagh (Cardiff UP 1967). ‘Ussher contributed to the Annals by lending the Book of Lecan to Connell Mageoghegan who provided it, or a copy, to Micheál Ó Cleirigh.’ See also fFtns 293, 298: the wholesale condemnation of Ussher derives a misinterpretation by C. R. Elrington of an ambiguous phrase in one of his letters to Bedell, corrected by William O’Sullivan in Irish Hist. Stud. 16, 12 (Sept. 1968), 215-19. In a letter of 30 July 1628, Bedell asked Ussher to procure Nehemiah O’Donnellan’s translation of the Psalms into Irish; Bedell’s translator Murtagh King was probably protected by Ussher on his instance. [Joseph Leerssen, Mere Irish & Fíor Ghael (1986), p.328.] Also: Constantia Maxwell, Robert Ussher [a nephew of the prelate] is chiefly noted as having strengthened the national element in the College by promoting the study of Irish. [Leerssen, ibid., p.329). Bibl. R. Buick Knox, James Ussher archbishop of Armagh (Cardiff, Univ. of Wales Press 1967). [See Dempster Controversy - infra.]

Roy Foster, Modern Ireland (1988), among the students admitted at foundation of TCD; Professor of Divinity, 1607; Archb. of Armagh, 1625; obstructed Bedell’s Bible scheme; attempted to introduce Anglican articles to Irish Church, 1634; Bishop of Carlisle, 1642; retired under pressure to discuss state of Protestantism with Cromwell. Ussher set the date of creation at 4004 b.c. [the date 23 Oct. given on BBC Reith Lecture on ‘Time,’ Dec. 1991]

[ top ]

Robert E. Ward, et al., eds, Letters of Charles O’Conor of Belanagare (Cath. Univ. of America Press 1988), Ussher and Ware called into question the existence of writing in pre-Patrician Ireland, had done irreparable damage to Irish historiography and had lent credence to the prejudice that before the coming of Christianity the Irish were savages. (p.xxiv.); Ussher ... claimed that the Christianity of the early Irish was not in conformity to Rome because the Church was a national church not subject to the Pope, just as the Anglican Church is (p.152, n.3; attached to Pyle stern repudiation of the same idea as echoed in Ferdinando Warner).

Norman Vance, Irish Literature, A Social History (Basil Blackwell 1990), Chap. 2, Seventeenth-century Beginnings, Archbishop Ussher and the Earl of Roscommon, Protestant Episcopalian counterclaims to continuity with ancient Irish and British Church independent of Rome [was] one of Ussher’s major scholarly projects; Ussher refutes extravagant Presbyterian prophetic biblical exegesis, see Refutation of J. H. [as above]; but note that a writing of his own, apparently forecasting the 1641 Rebellion, was reprinted up to the time of its inclusion with Thomas Rhymer, The Whole Prophecies of Scotland, England, Ireland, France, and Denmark ... [and] Bishop Ussher’s Wonderful Prophecies of the Times (Edinburgh [1810]); section on ‘Archbishop Ussher’, 40-57; ‘great luminary of Irish church’ recently condemned as intellectual reactionary (by Trevor Roper, Hugh Trevor Roper, ‘James Ussher’, in Catholics, Anglicans and Puritans (London: Secker & Warburg 1985). Focuses on speech before the Lord Deputy, calling for strong army against possible Irish-Spanish alliance, and recruitment of loyal Irishmen; complains that the ‘English-Irish’ are ‘not truly distinguished fro[m] the meere Irish’ and are ‘no better thought of in their loyaltie than the meere Irish’; brought up in minimal conformism and Calvinism; strained relations with Laud; ); Ussher wrote Apostolical Institution of Episcopacy (1641), which provoked Milton’s Of Prelatical Episcopacy (1641), savagely attacking Ussher use of letters attributed to St Ignatius. Vance notes that Ussher’s his mother may have been Catholic, like her brother (Richard Stanihurst), a claim made in Commentarius Rinucinnianus (1658): ‘si non patre, certe matre Catholica’. Ussher was also related to Henry Fitzsimons, the Jesuit controversialist and Prof. of Philosophy at Douai, who was invited to take part in a debate with Ussher while imprisoned in Dublin Castle. A variant account exists giving Cardiff as the place he died.

Anthony Alcock, Understanding Ulster (Lurgan: Ulster Society [Northern Whig] 1994) - biographical notice: Ussher, ed. TCD tolerated Puritanism; convocation took place in Dublin 1615, Ussher responsible for drafting articles of Church; his mentor was John Foxe; thought first seven hundred years of Christian Church was relatively golden period followed by three centuries of growing worldliness and corruption; by eleventh century the Anti-Christ had been firmly established in Rome; Foxe and Ussher abominated Gregory VII; saw Reformation as reversal of Roman aberration and return to true path.

Alcock comments: ‘In so far as Ireland was concerned Ussher’s defence of the continuity and autonomy of the churches in the West was designed to show that the Church of Ireland was the only true successor to the Church of the Apostolic era, and not the Roman Catholic Church. That raised the question as to what attitude should be adopted to Roman Catholics. To what extent should they be tolerated? ... Ussher drafted 104 Articles, the contents of which did not seriously depart from the Thirty-Nine Articles adopted in England in 1562. They did, however, include articles drawn up by Archbishop Whitgate in 1585 who was trying to enable Calvinist divines to remain in the Anglican Church. These Calvinistic tendencies were particularly appealing to Scottish settlers in Ulster and as a result many Scottish ministers were appointed to the Irish Church.

[Alcock cont..:] Unfortunately the Church of England in the person of Archbishop Laud, wanted to introduce theological uniformity throughout the British Isles. He particularly dislike the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. Among the many duties undertaken by Thomas Wentworth when he went to govern Ireland in 1633 was to carry out Laudian reforms. He tried to get the now established Church of Ireland to abandon the 1615 Articles in favour of those accepted by the Church of England in 1614. He also sought to have the Scottish settlers in Ulster accept the Episcopal system of government which King Charles I was trying to impose on the Scottish Church, and which the Scottish Church was resisting. To this end Wentworth required all Scottish settlers to swear the so-called Black Oath ... many refused, many fled ...&c.’ (pp.11-12.)Muriel McCarthy & Caroline Sherwood-Smith, eds., Hibernia Resurgens: Catalogue of Marsh’s Library (1994), give details: archbishop of Armagh for 30 years; given state funeral by Cromwell in Westminster Abbey, though at the expense of his only dg. and her husband; concerned with eleven bishops in issuing joint-declaration against religious toleration, but rumoured to have turned Catholic on his death-bed (meaning, presumably, suspected of carrying antiquarian interest over into religious sympathy); at first turned down Provostship of TCD in 1610 as detracting from his time for scholarship; permitted Fr. Matthews and Thomas Strange OFM to use his library; exchanged information with Luke Wadding and David Rothe; long-standing belief that he was opposed to Bedell’s Bible arose from 19th c. misreading of his letters; one of the earliest to consider Irish a Indo-European language; corresponded with Lodewijk de Dieu of Leiden on relationship of Irish to Persian, writing of Irish, ‘Est quidem lingua haex et elegans cum primis, et opulenta’. Note that McCarthy record also, ‘the protectorate army bought the books and presented them to the college library with the result that they came to their intended home in the end’ [presum. err. for gift of Charles II].

John McCafferty, ‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, in Irish Studies Review, April 1998, pp.87-101. Was St Patrick, in essence, a Protestant? Versions of that question have been asked for over four centuries and there are some who still ask it. A good place to start examining this long fascination is on 14 October 1932, during the closing stages of a conference organised by the Church of Ireland to commemorate the 1,500th anniversary of the arrival of Patrick. In a sermon preached at the final service, the Archbishop of Dublin, John Gregg, offered a strident defence of his church and its mission: ‘The Church of Ireland is the most Irish thing there is in Ireland. It holds its apostolic ministry in unbroken descent from the Celtic bishops who succeeded Patrick’. The Church of Ireland, then, was the true Irish Church, descendant of the father of Irish Christianity. ‘Today [Gregg went on] the Church of Ireland turns neither to Windsor nor to Rome for the appointment of its bishops. It is an Irish self-governing organisation, as free from the intervention of Britain or the Vatican as the Celtic church was in the days of Columba’. The Church of Ireland had regained its primitive independence, governing its own affairs for the spiritual benefit of the Irish people - a people, Gregg had to admit, ‘the main body of [whom] refuse to be in communion with us’. Nevertheless, the people ‘should from time to time have plainly set before them the historical facts concerning the church which claims to be their own - those facts may set some of them thinking and asking pertinent questions. So, in 1932, the Archbishop of Dublin could assert that the Church of Ireland was the true heir of Patrick, that it enjoyed by right the independence and self-government of the early Irish Church and that if only people cared to acknowledge these historical facts they would see that true Catholicism was to be found not in Rome but with ‘the most Irish thing there is in Ireland’. [87] (Cont.)

[ top ]

John McCafferty (‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, 1998) - cont.: McCafferty locates Ussher as chief spokesman in Ireland for the Protestant right to ecclesiastical tenure on that soil, answering the Controversialists question, ‘Where was you Church before Henry Tudor’s lust imposed it on us? Is your Church not a foreign implant?’ (p.89) Gives account of the Protestant scheme of history acc. to which the Church degenerated from its foundation, climactically with the loosing into the world of the Anti-Christ in 1000 AD, documented in Ussher’s Gravissimae Questionis de Christianarum Ecclesiarum (1613). ‘The religion of the papists is superstitious and idolatrous; their faith and doctrine, erroneous and [89] heretical’ (The Protestation of the Archbishops and Bishops of Ireland against the Toleration of Popery Agreed Upon and Subscribed by Them at Dublin, the 26 of November 1626, London 1641). McCaffety regards the Discourse not just intended as a scholarly rebuttal of Catholic claims [but] an evangelical torch to dispel the Antichristian darkness of Rome. [90]. Quotes: ‘The religion professed by the ancient bishops, priests, monks, and other Christians in this land was for substance the very same with that which [now] by public authority is maintained therein’ [Whole Works, VI, p.238; here 90]. The Discourse was intended to rescue Catholics not to fuel fratricidal strife between Protestants. [91]; Because he tended to use evidence from Britain as ancillary to that from Ireland, Ussher could show that while there was cordial agreement between the Irish and British Churches, the tradition of the Church of Ireland still descended directly from Patrick. Thus his own Church of Ireland was autonomous, under its Primate, answering only to Charles I - but Charles as King of Ireland, not King of England. Elsewhere in the Discourse, Ussher was at great pains to prove that the kingdom of Ireland was no sixteenth-century fabrication of Henry VIII, but a thing attested from the much earlier times.’ (Discourse) The book intended to demonstrate that it was an act of profound patriotism to be a member of the Church of Ireland. Acknowledgement of the Pope’s power in matters spiritual was nothing less than an affront to the ancient dignity of the kingdom of Ireland. The whole of the Discourse is peppered with expressions such as ‘our ancestors’, ‘our Patrick’, ‘our Brendan’, ‘our ancient church’ - all calculated to inspire pride in the country and in its national church.’ (Discourse) [92]; Prayers for the dead dismissed as prayers for those ‘not doubted to be in heaven’ [93]. (Cont.)

John McCafferty (‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, 1998) - cont.: ‘The stumbling block presented by the twelfth century was considerable. On the one hand, it was a time when the church in Ireland could, through a series of synods, be said to have acknowledged the suzerainty of Rome and to have caused the dominion of Antichrist to spread across the land. On the other hand, Ussher knew that the current diocesan system had been erected by these same synods. Around the same time came conquest and the rule of Henry II, but along with these political events went the licence of the papal bull Laudabiliter. Ussher had the tough task of having to smash Laudabiliter, condemn the pope’s presumption in making such a grant, but not diminish in any way Henry II’s title to Ireland. He was forced to play up the submission of the Irish episcopacy to Henry as king and lord in 1171. The conjunction of assumption of power by the Roman Antichrist over Ireland with the arrival of the English king was a messy and unfortunate business, and with his providential scheme of church history, Ussher sought to divert attention from the potentially destructive clash of his political loyalties. He was wide open to the taunt that Antichrist and English rule came very close to one another, as well as to the more mundane charge that the title of the English king had been dependent on the papacy. The diversion came in the form of a blistering attack on O’Sullivan Beare (with whom Ussher had already crossed swords) and a trenchant (though uncharacteristically unsubstantiated) assertion that twelfth-century Ireland was ‘esteemed a kingdom, and the kings of England accounted no less kings thereof’. (Works, IV, 369) [95]. (See longer extracts in RICORSO Library > Criticism > Monographs - via index or as attached.)

[ top ]

Elizabethanne Boran, ‘Reading Theology with the community of Believers: James Ussher’s “Directions”’, in Bernadette Cunningham and Máire Kennedy, eds., The Experience of Reading: Irish Historical Perspectives (Dublin: Rare Books Group [… &c.] 1999), pp.39-59: quotes J. Richard Parr, The Life of the Most Reverend Father in God, James Ussher, late Arch-Bishop of Armagh, Primate and Metropolitan of all Ireland (London 1686): ‘To avoid giving the persons intended to be wrought upon, an alarm before-hand, thatn their faults, or errors were designed to be attacked; for then the person concerned, look upon the preacher as an enemy, and set themselves upon their guard. On such occasions he rather recommended the choosing of a text, that stood only upon the borders of the difficult subject; and if it might be, seemed more to favour it; that so the obnoxious hearers, may be rather surprised, and underminded, than stormed, and fought with: And so the preacher, as St Paul expressed it, being crafty, may take them with guile.’ (Parr, p.16; here p.89.)

Patrick O’Sullivan [Diaspora List, Bradford, 23 July 1998], writes that the old canard that Ussher was hostile to the Irish language as, regarding it as barbaric and uncultured, has been rebutted by William O’Sullivan, Irish Historical Studies, XVI, No. 62 (Sept. 1968), pp.215-19, and Joep Leerssen, Studia Hibernica, XXII-XXIII (1982-3), pp.50-58; see Alan Ford, reviewing Parry, The Trophies of Time: English Antiquarians of the 17th century (1995), in Irish Historical Studies, Vol. XXXI, No. 121 (May 1998)].

[ top ]

Quotations

Discourse of the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish and British (1631), ‘Onely this I will say, that as it is most likely, that S. Patrick had a speciall regard unto the Church of Rome, from whence he was sent for the conversion of this Island, so if I my self had lived in his dayes, for the resolution of a doubtful question I should as willingly have listened to the judgement of the Church of Rome, as to the determination of anie Church in the whole world; so reverend an estimation have I of the integritie of that Church, as it stood in those good dayes. But that S. Patrick was of opinion, that the Church of Rome was sure ever afterward to continue in that good state, and that there was a perpetuall priviledge annexed unto that See, that it should never erre in judgement, or that the Popes sentences were always to be held as infallible Oracles; that I will never beleeve, sure I am, that my countrey men after him were of a farre other beleefe; who were so far from submitting themselves in this sort to whatsoever should proceed from the See of Rome, that they oftentimes stood out against it, when they had cause so to do […]’ [q. source; but note that the above is glossed without quotation in McCafferty, op. cit., as meaning that while ‘Patrick had special regard for Rome … which was entirely justified in those days before corruption, he acknowleged no dependence on the See, nor did he believe that Rome had any special privilege attached to it’; see John McCafferty, ‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, in Irish Studies Review, April 1998, p.95].

The Scoti: ‘[I]n those elder times [...] was common to the inhabitants fo the greater and the lesser Scotland [...] that is to say, of Ireland, and of the famous colony deduced from thence into Albania’; further, ‘The religion [...] received by both was the self same; and differed little or nothing from that which was maintained by their neighbours the Britons.’ (Quoted in John McCafferty, ‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, Irish Studies Review, April 1998, pp.91-92.)

Proto-Protestant Ireland: ‘The religon professed by the ancient bishops, priests, monks and other Christians in this land was for substance the very same with that which now by publike authoritie is maintained herein.’ (Quoted by Fintan O’Toole reviewing Marcus Tanner, Ireland’s Holy Wars: The Struggle for a Nation’s Soul 1500-2000, Yale UP 2001, in The New Republic, 16 & 26 Aug. 2002, pp.45.)

Onora na hEireann: Remarking that Ireland was counted as one of the four antique kingdoms of Europe at the Council of Constance, Ussher writes: ‘And this I have here inserted all the more willingly, because it makes something for the honour of my country, to which, I confess, I am very much devoted.’ (Whole Works, IV, pp.369-70; McCaffrey, op. cit., 1998, p.99.)

Ussher’s Chronology: cited as source of his dating of the age and creation of the world: Annales veteris testamenti, a prima mundi origine deducti: una cum rerum Asiaticarum et Aegyptiacarum chronico, a temporis historici principio usque ad Maccabaicorum initia producto [Annals of the Old Testament, deduced from the first origins of the world, the chronicle of Asiatic and Egyptian matters together produced from the beginning of historical time up to the beginnings of Maccabees] (London 1650). See Wikipedia’s Ussher entry - online; accessed 26.05.2021.]

[ top ]

Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.II [of 2] (London & Dublin 1821), pp.610-15 |

A LEARNED antiquary and illustrious prelate, distinguished by Dr. Johnson as the great luminary of the Irish church, was born in Dublin on January 4th, 1580. He was descended from an ancient and respectable family, which had settled in Ireland in the reign of Henry II. On which occasion it followed a common custom of the times in exchanging its English name of Nevil, for that of the office with which it was invested. His infancy is rendered somewhat singular by the circumstance of his having been instructed in reading by two aunts who had been blind from their cradle, but who, from the retentiveness of their memory, were able to repeat with accuracy nearly the whole of the Bible. James I, then only king of Scotland, had deputed two young Scotsmen, of respectable families, to Ireland, for the purpose of keeping up a correspondence there to secure his peaceable succession on the death of Elizabeth. To hide their real business, they opened a school in Dublin, to which young Usher was sent at the age of [610] tight years; and after profiting much under so excellent a tuition, he was admitted into the college of Dublin in 1393, the very year in which it was finished. He was one of the three first students who were admitted, and his name still stands in the first line of the roll. Here he contracted-a great fondness for history, and at the early age of fourteen, commenced a series of extracts from all the historical writers he could procure; by persevering in which, we are informed, that he was little more than fifteen when he had drawn up an exact chronology of the Bible, as far as the Book of Kings, little differing from his "Annales,” which have since been published. He shortly after applied himself with much diligence to the study of controversy, and engaged, when in his nineteenth year, in a public disputation with the learned Jesuit Fitzsimons, the result of which is variously reported, but appears from a letter of Usher’s, inserted in his “Life by Dr. Parr,” to have been in his favour, Fitzsimons having declined to continue it. In 1600, he was admitted master of arts, and appointed proctor and catechetical lecturer of the university; and in the succeeding year, in consideration of his extraordinary acquirements; he was ordained deacon and priest; though under canonical age, by his uncle, Henry Ussher; then archbishop of Armagh. He was shortly after appointed afternoon preacher at Christchurch, Dublin; where he canvassed the different controversial points at issue between the Catholics and Protestants, constantly opposing a toleration which was then solicited by the former. On one ooccasion, referring to a prophecy of Ezekiel, be observed, “from this year, I reckon forty years; and then those whom you now embrace shall be your ruin, and you shall bear their iniquity.” This was afterwards, at the Rebellion in 1641, converted into a prophecy, and there was even a treatise published, “De Predictionibus Usserii." [...] |

| See full copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > History > Legacy - via index or as attached |

Charles Read, ed., A Cabinet of Irish Literature (3 vols., 1876-78), selects ‘Of Meditation’, from A Method for Meditation (London 1656); ‘How Adam and Eve Broke all the Commandments at Once’, from The Body of Divinity, 5th ed. (1658); and ‘On the Oath of Supremacy’, from rare work Clavi Trabales, or Nailes fastened by so[me] great Masters of Assemblyes, with a pref. by the Lord-bishop of Lincoln, a speech delivered in the Castle Chamber at Dublin, 22 Nov. 1622, at the censuring of some officers who refused to take the oath of supremacy. By the Primate Usher, then Bishop of Meath’; Read calls this the only time he raised his ben against the cavaliers; but in it he instances the argument that the form of the oath requires ‘a full resolution of conscience’, and goes on to ‘clear this point and remove all needless scruples out of men’s minds’, invoking the Pauline injunction to obey sovereignty, and the civil duty to provide for the moral welfare of citizens]. CAB calls Ussher Irish of long-continued descent; from a Nevil, the train of King John, office of Usher; first ed. two blind aunts, intellectual and religious; then ed. by Scotsman, in disguise, actually Jacobites; collected materials of Annals of the Old and New Testament; controversy with Jesuit Henry Fitz-Symonds, prisoner in Dublin Castle; responded to the latter’s taunts of youth; MA 1600; proctor and lecturer, ord. by his uncle, Archbishop of Armagh; sermon prophecy, ‘for this year I reckon forty years; and then those whom you now embrace shall be your ruin, and you shall bear their iniquity’ (viz., Rebellion); proceeded to London with Dr Luke Challoner to buy books for TCD, 1603; BD, 1607; Chancellor of St. Patrick’s; Camden (1551-1623), visiting, concludes his description of Ireland in Britannia, ‘Most of which I acknowledge to owe to the diligence and labour of James Usher [sic], chancellor of the church of St. Patrick, who in various learning and judgement far exceeds his years’; professor of Divinity at 26; visited London in 1609, and became acquainted with Selden, Sir Robt. Cotton, Lydiat, Dr Davenant; afterwards stayed by rule three moths each three years; elected provost of TCD, 1610, but refused; 1612, DD; De Ecclesiarum Christianarum Successione et Statu (1613); printed with Antiquities of the British Churches (1687 ed.); m. dg. of Luke Challoner; made Bishop of Meath by James I, London 1619; appointed by James to collect material for eccles. history of England, Ireland, and Scotland; appt. Archb. of Armagh, [being the] 21st, six days before death of James I (27 March); received £400 out of treasury of Charles I; employed British merchant at Aleppo to buy oriental writings incl. Samaritan Pentateuch, and copy of OT in Syriac, now in Bodleian; [details of his English career follow]; his library seize [sic] for refusal to present himself at the Assembly of Divines, 1643, to remodel the Church; Dr. Featly obtained it for his own use; published On the Lawfulness of Levying War against the King; Historical Disquisitions touching Lesser Asia, and The Epistles of Saint Ignatius; retired to Cardiff Castle, commanded by Sir T. Tyrrel, who had married his dg.; moved to castle of St. Donats, invited by Dowager Lady Stradling; his manuscripts broken into by thieves and flung about; rescued by county gentlemen; moved to London to house of Lady Peterborough, 1646; preacher of Lincoln’s Inn, 1646; called for advice by King at Carisbrooke Castle; watched execution from roof of Peterborough House; Annals of the Old Testament (1650-54); pleaded cause of English clergy before Cromwell, 1654 and 1655; taken ill and died, 20 Mar.; Cromwell ordered his interment at Westminster Abbey, 17 April; his library sought by Kings of Denmark and Mazarin; Cromwell had it purchased by army and stored in Dublin Castle; other works, Solar Calculations of the Syrians; On the Apostles’ Creed and other Ancient Confessions of Faith; De Graeca Septuaginta; Ecclesiastical Antiquities of the British Church, of which Gibbon ‘all that learning can extract from the rubbish of the dark ages is copiously stated in Archbishop Usher’; Jebb calls him ‘the most profoundly learned offspring of the Reformation’; and Johnson, ‘Usher is the great luminary of the Irish church; and a greater no church can boast of’. [... &c.]

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 1 selects A Discourse of the Religion Anciently Professed by the Irish and the British [251-52]; BIOG, 271 [this notice taken directly from DIB], bishop of Meath, 1621; although a Royalist, he advised Charles I against the execution of Strafford bishop of Carlisle, and later resided in Oxford and then in Wales; WORKS & CRIT [see supra]; 237 [counted with Ware, Wadding and Colgan as ‘scientific’ historians of the age]; 1291 [patristic scholar who devoted much of his energies to the cause of a distinctive Irish reformed church]. FDA2 the idea of the Celt … was received wisdom of the Church of Ireland [tracing itself from St. Patrick] since the days of Archbishop Ussher [Terence Brown, ed.], 519; Aodh de Blacam (Studies 1934), ‘In the seventeenth century, the University [TCD], like Ussher himself, was not unfriendly to Irish historical studies’; ftn. Ussher attempted to prevent use of Irish in Church of Ireland by, among other things, obstructing Bedell’s Irish translation of the Bible, an avid student of early Irish history [Luke Gibbon, ed.], 1016 [but see infra, Leerssen].

John McCafferty, ‘St Patrick for the Church of Ireland: James Ussher’s Discourse’, in Irish Studies Review, April 1998, pp.87-101, incls. bibliography: Ute Lotz Heumann, ‘The Protestant Interpretation of History in Ireland: The Case of James Ussher’, in B. Gordon, ed ., Protestant History and Identity in Sixteenth Century Europe, Vol. II: The Later Reformation (Aldershot 1996), pp.107-20; Alan Ford, The Protestant Reformation in Ireland, 1590-1641 (Frankfurt 1987); Declan Gaffney, ‘The Practice of Religious Controversy in Dublin 1600-1641, in W. J. Shiels and Diana Ward, eds ., The Churches, Ireland and the Irish (London 1989), pp.145-58; Bernadette Cunningham, ‘The Culture and Ideology of the Irish Franciscans at Louvain 1607-1650, in Ciaran Brady, ed., Ideology and the Historians (Dublin 1991), pp.11-30; C. R. Elrington & J. H. Todd, eds., The Whole Works of … James Ussher, 17 vols. (Dublin 1847-64); Alan Ford, ‘The Church of Ireland 1588-1641: A Puritan Church?’, in A. Ford, J. I. McGuire, & K. Milne, eds., As by law Established (Dublin 1995) [q.pp.]; for discussion of Dempster controversy, see Joep Leerssen, Mere Irish and Fíor Ghael, 2nd ed. (Cork UP 1996 [rep. edn.]), pp.263-77; Bernadette Cunningham & Raymond Gillespie, ‘“The most adaptable of saints”: The Cult of St. Patrick in the Seventeenth Century’, in Archivium Hibernicum, Vol. 49 (1995), pp.92-93; McCaffrey, ‘“God bless your free Church of Ireland”: Wentworth, Laud, Bramhall and the Irish Convocation of 1634’, in J. F. Merritt, ed., The Political World of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford (Cambridge 1996), pp.187-208; Joep Leerssen, ‘Archbishop Ussher and the Gaelic Past’, in Studia Hibernica, Vols. 22-23 (1982-23), pp.50-58; William Monck Mason, The Catholic Religion of St. Patrick and St. Columbkill (Dublin 1822); Nelson McCausland, Patrick Apostle of Ulster: A Protestant View of St. Patrick (Belfast 1997).

Hyland Books (Cat. 224) lists A Body of Divinity, or the Summe and Substance of Christian Religion [1st edn.] (1648), port.

Univ. of Ulster (Morris Collection) holds Nicholas Bernard, The Life and Death of the Most Reverend and Learned Father of Our Church Dr. James Usher, Late Arch-Bishop of Armagh, and Primate of All Ireland, published in a sermon at his funeral at the Abbey of Westminster, April 17, 1656, Printed by E. Tyler (1656) [12], 119, [6] p.; also Charles Richard Elrington, Life of the Most Rev. James Ussher, DD, Lord Archb. of Armagh, and Primate of All Ireland, with an account of his writings (Hodges and Figgis 1848) [var. Hodges & Smith 1847].

Library of Herbert Bell (Belfast) holds An Answer To Challenge (London 1631); A Brief Declaration London 1631); A Sermon Preached Before The House of Commons (London 1631); A Speech Delivered in the Castle Chamber at Dublin (London 1631); A Discourse of The Religion of The Irish v. British (London 1638).

[ top ]

Notes

Dr. Johnson: Ussher was called ‘the greatest luminary of the Irish Church’ by Dr. Johnson, and described on the continent as ‘catholicorum doctissimus’, while Bishop Jebb called him ‘the most profoundly learned offspring of the Reformation’ (Quoted Rev. Alexander Leeper, DD, Canon of St Patrick’s, Historical Handbook of St Patrick’s Cathedral (1891, p.47.)

The Chronology: Disraeli’s Coningsby contains an allusion to his famous chronology, as does the the film, Inherit the Wind.

Sylvester O’Halloran wrote of Ussher: ‘[O]ur great primate Usher [Ussher] who, though not of Irish descent, yet thought the glory of his country worth contending for, and adverting harshly to “the Caledonian plagiary”.’ (Letter to the Dublin Magazine, signed ‘Miso-Dolos’, Jan 1763 p.21-22; headed ‘The poems of Ossine, the son of Fionne Mac Comhal, reclaimed’; quoted in Joep Leerssen, Mere Irish and Fíor Ghael, 1986, p.401.)

Catholic convert? Various sources (incl. Cleeve & Brady, Dictionary of Irish Writers) suggest that he was intensely hostile to Bishop Laud and died a Roman Catholic. (See also Norman Vance in Commentary, supra.)

George A. Little (Dublin Before the Vikings, 1957) remarks that Archbishop Us[s]her in his Primordia, explains ‘baile’ [town] as oppidum (p.861); further, Ussher’s Epist. Hist. Syll., N. 8, contains Livinius’ poetical epistle to Abbot Florbert (q.p.)

St. Antoninus: Ussher is said to have used St. Antoninus’s Historiorum Chronicarum (1480) as a basis of his life of Patrick in 1639 (Thomas Kobdebo, ed., Treasures of Maynooth Library; see further under Fitzgeralds.)

John Colgan: lacking direct access to texts on St. Patrick in compiling his Triadas Thaumaturga (1647), Colgan cited those fragments of Tirechan and Murchu which he had found quoted in Ussher’s Britannicarum Ecclesiarum Antiquitates of 1639 [De Burca 44; 1997, p.10.]

TCD Library: Ussher amassed 10,000 books, assigned to TCD Lib. through intervention of Charles II. His collection inclues manuscripts and texts by Bainbridge, Roger Fry, Galileo. Also Irish, Greek, and Arabic, and mss of the Waldenses, a religious party resistant to Rome. Ussher collated the Book of Kells with the Book of Durrow in 1621, registering that the Book of Kells had then four more leaves than now.

Codex Armachanus: his marginal notes are visible on the late 14th century Latin MS Vitae Sanctorum Hibernicorum, otherwise the Codex Armachanus, now in Marsh’s Library (MS 122 fols.)

Portrait: There is a portrait of Ussher doubtfully attrib. to Sir Peter Lely, oil; see Anne Crookshank, ed., Irish Portraits Exhibition (Ulster Museum 1965).

[ top ]