Life

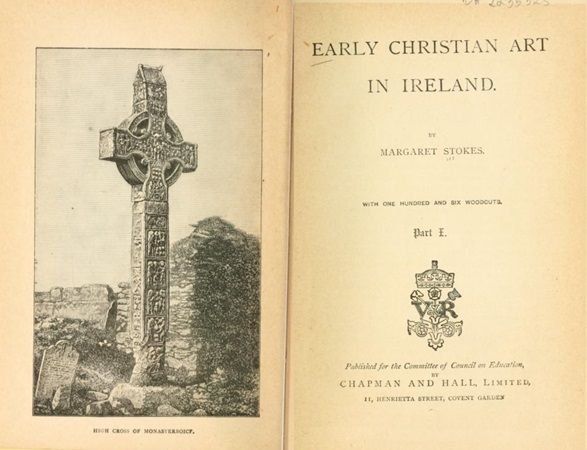

1832-1900 [Margaret M’Nair Stokes; freq. Miss Stokes]; Irish archaeologist; dg. William Stokes; The Cromlech on Howth (1861) is an illuminated edition of Ferguson’s poem; author of Early Christian Art In Ireland (London 1887; Dublin edn. 1911), with 106 of her own ills. incl. High Cross of Monasterboice as front.; ed. and illustrated Dunraven’s Notes on Irish Architecture, 1875-77; her High Crosses of Ireland (1898) was published unfinished at her death; MRIA and mbr. of Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland; papers held in TCD. CAB ODNB JMC

[ top ]

Works

Early Christian Art in Ireland [Committee of Council of Education; South Kensington Museum Art Handbooks] (London: Chapman & Hall 1887), xvi, 210pp., ill. [106 woodcuts based on pencil drawings by Stokes; bibl. refs. on pp.52, 116, 142, 198; index.] (COPAC & Internet Arch.); added ills. [‘drawings from nature’] to Ferguson’s Cromlech’s of Howth, rev. by George Petrie (London: Day & Son 1861); also drew ills. for Petrie’s Christian Inscriptions in the Irish Language, 2 vols. (Dublin UP [TCD] 1872-78). [See De Burca Cat. - online; accessed 20.02.2024]

Early Christian Art in Ireland (1887) - with High Cross of Monasterboice (front.).

|

Commentary

Oscar Wilde, review of Early Christian Art, in Pall Mall Gazette (17 Dec. 1887): ‘The want of a good series of popular handbooks on Irish art has long been felt, the works of Sir William Wilde, Petrie, and others being somewhat too elaborate for the ordinary student; so we are glad to notice the appearance, under the auspices of the Committee of the Council on Education, of Miss Margaret Stokes’s useful little volume on the early Christian art of her country. There is, of course, nothing particular original in Miss Stokes’s book, nor can she said to be an very attractive or pleasing writer, but it is unfair to look for original[ity] in primers, and the charm of the illustrations fully atones for the somewhat heavy and pedantic character of the style. [... &c.]. See Wilde About Wilde Newsletter, ed. Margaret McCaffrey, No.17 (16 Oct. 1994), pp.15-16.

| P. W. Joyce, A Short History of Ireland from the Earliest Times to 1608 (London: Longman 1893) - |

The Book of Kells, a vellum manuscript of the Four Gospels, probably written in the seventh century, is the most beautifully written Irish book in existence. Each verse begins with an ornamental capital; and upon these capitals, which are nearly all differently designed, the artist put forth his utmost efforts. Miss Stokes, who has examined the Book of Kells with great care, thus speaks of it: ' No effort hitherto made to transcribe any one page of this book has the perfection of execution and rich harmony of colour which belongs to this wonderful book. It is no exaggeration to say that, as with the microscopic works of nature, the stronger the magnifying power brought to bear upon it, the more is this perfection seen. No single false interlacement or uneven curve in the spirals, no faint trace of a trembling hand or wandering thought can be detected. This is the very passion of labour and devotion, and thus did the Irish scribe work to glorify his book.’ [n.] ' Early CIiristia?i Arehitecture in Ireland, p. 127. See p. 18 supra. |

| Note: Joyce later cites Stokes on the age of Celtic crosses: ‘Miss Stokes gives the dates of the stone crosses as extending over a period from the tenth to the thirteenth century inclusive.’ (Ibid., p.108; without ref.) |

George A. Little, ‘The provenance of the Church of St Michael de le Pole’, in Dublin Historical Record, 12, 1 (Feb. 1951), pp.2-13, contains adverse remarks on the antiquarianism of Miss Stokes regarding her grouping of St Kevin’s of Glendalough with towers bonded to churches in design, a view supported by her inclusion of a sketch by Bèranger in Early Christian Architecture in Ireland. in fact as P. J. O’Reilly has pointed out the ‘church’ was a schoolhouse added by a certain Jones in 1707; likewise in her edition of Dunraven’s Notes on Irish Architecture, she placed St Michael de la Pole’s among that group; Little considers that the conditions governing her term ‘joined’ in the list in the latter work are unsure (p.3); Little ascribes Bèranger’s drawing to about the year 1778 on the basis of evidence in his note appended to the undated sketch in the RIA collection, to the effect that he had mislaid it when he ought have published it, and that the church was directly afterwards demolished. [&c.]

Joep Leerssen, Remembrance and Imagination [...] (Cork UP/FDA 1996) notes that Margaret Stokes’s Early Christian Architecture in Ireland (1878) was the work which ‘most of all [...] has settled the question as to the origin and dating of the Round Towers’ - i.e., concurring with George Petrie as placing them in monastic Ireland rather than the pagan period associated with Phoenician and ‘fire-tower/phallic’ theories.

[ top ]

Quotations

Early Christian Art in Ireland (1887): ‘The subject of the following chapters is what has been often mis-named Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, or Runic Art, whereas the style is Irish. The term Celtic belongs to the arts of bronze and gold and enamel practised in Britain before the Roman occupation, and in Ireland before the introduction of Christianity in the fifth century. It also embraces the great stone forts that line the western coasts of the country, such as Dun Aengus and Dun Conor, as well as the chambered tombs of New Grange. The late Celtic style in Great Britain, the bronzes of which are marked by distinct characteristics in decoration, prevailed from about two hundred years before the birth of Christ to the time of the Roman occupation. It lingered to a much later date in Ireland. Early Celtic goes back much farther into a prehistoric region in which we cannot trace similar peculiarities of decorative design. The early Christian Art of Ireland may well be termed Scotic as well as Irish, just as the first missionaries from Ireland to the Continent were termed Scots, Ireland having borne the name of Scotia for many centuries before it was transferred to North Britain ; and foreign chroniclers of the ninth century speak of “Hibernia, island of the Scots,” when referring to events in Ireland regarding which corresponding entries are found in the annals of that country. [...]

The peculiarity of Irish Art may be said to be the union of such primitive rhythmical designs as are common to barbarous nations, with a style which accords with the highest laws of the arts of design, the exhibition of a fine architectural feeling in the distribution of parts, and such delicate and perfect execution, whatever the material in which the art was treated, as must command respect for the conscientious artist by whom the work was carried out.’ (Early Christian Art, 1887; Pref. pp.[vii], viii.)

‘The Tara brooch and the Ardagh chalice offer the most perfect examples of the use of this peculiar spiral that have been found in the metal-work of Irish Christian Art; and we are strongly reminded of the decoration of Irish manuscripts from the “Book of Kells,” circa 690, when we study them. That these two relics are contemporaneous one with another there can be little doubt. They show not only perfectly similar developments of this spiral design, but many other points of agreement besides. The same filigree wire-work ; the same Trichinopoli chain-work ; the same circles of amber and translucent glass ; the same enamels, both “cloisonn[é]s ” and “champlevés.”’ ( See Figs. 25, 26. Op. cit., p.75 - available online; accessed 20.02.2024..)

[ top ]

References

Irish Literature, ed. Justin McCarthy (Washington: University of America 1904); 1832-1900; dg. Dr. William Stokes; Early Christian Architecture in Ireland; ed. Christian Inscriptions in the Irish Language; illuminated ed. of Samuel Ferguson’s The Cromlech on Howth; contrib., drawings to Earl of Dunraven’s Notes on Irish Archaeology; unfinished book on High Crosses of Ireland; JMC selects ‘The Northmen in Ireland’ form Early Christian Architecture, from Early Christian Ireland, ‘When the group of humble dwellings which formed the monasteries and schools of Ireland is seen at the foot of the lofty tower whose masonry rarely seems to correspond in date with the buildings that surround it, and which does not, as elsewhere, seem a component and accessory part of the whole pile that formed the feudal abbey, we cannot but feel that some new condition in the history of the Irish Church must have arisen to account for the apparition of these bold and lofty structures. ... In the beginning of the ninth century a new state of things was ushered in, and a change took place in the hitherto unmolested condition of the Church. Ireland became the battlefield of the first struggle between paganism and Christianity in Western Europe; and the result of the effort then made in defence of her faith is marked in the ecclesiastical architecture of the country by the apparently simultaneous erection of a number of lofty towers, rising in strength of “defence and faithfulness of watch” before the doorways of those churches most liable to be attacked. For seven centuries Christianity had steadily advanced in Western Europe. At first silent and unseen, we feel how wondrously it grew, until, in the reign of Charlemagne, it became an instrument in the hands of one whose mission was to strengthen his borders against the heathen, and to establish a Christian monarchy. [In the ensuing paragraphs, she attributes the impetus of the Viking invasion to the pressure exerted by the Carolingian order in Northern Europe following the invasion of Saxony in 772 AD]; gives extract on ‘Northmen in Ireland’ from Early Christian Architecture.

Library of Herbert Bell, Belfast, holds Early Christian Art in Ireland (London 1887), another edn. (Dublin 1911); Three Months in The Forest of France (London 1895).

Hyland Books (Cat. 219; [1995]) lists Art Readings for 1880 (Alexandra College Literary Soc.), Nos. 1-5 [23 up to 34pp. each]; also Readings on Archaeology and Art (1883), 71pp., full leather.

Belfast Public Library holds Early Christian Art in Ireland (1887).

University of Ulster Library, Morris Collection, holds Six Months in the Apennines ... in search of the vestiges of Irish saints in France (1892) 313p; Three Months in the Forests of France ... in search of the vestiges of Irish saints in France (1895) 291p.

Notes

Portrait, Margaret Stokes by Walter Osborne, chalk NGI; see Anne Crookshank, Irish Portraits Exhibition, Ulster Mus. (1965)

[ top ]