Life

| b. 24 Nov. 1713, Clonmel; son of impoverished English ensign of a family from Elvington, nr. York; lived in various barracks in Ireland until the regiment was decommissioned; his father badly injured in a duel; his mother held school as a seamstress in Dublin; ed. Hipperholme, Halifax Grammar School, Yorkshire [aetat. 10]. proceeded to Cambridge on the Archb. Sterne Schol.; befriended Hall-Stevenson [‘Eugenius’, who appears both in Tristram Shandy and in Sentimental Journey], and read Locke; contracted tuberculosis [TB]. ord., 1738; living at Sutton-on-the-Forest; given prebendary of York, 1741, m. Elizabeth Lumley [cousin of Eliz. Montagu], but unhappy; appt. Justice of the Peace [JP]. received the living of Sutton-on-the-Forest and Stillington, Yorkshire; indulged his interest in women; wrote miscellaneous journalism; wrote The History of a Good Warm Watchcoat, 1759 [formerly entitled A Political Romance], published posthumously, being a satire on eccles. courts which was burnt by Church authorities; passed parish to care of curate; |

| first version of vols. 1&2 of Tristram Shandy turned down by Dodsley; rewritten ‘under greatest heaviness of heart’ due to mental breakdown of wife and death of parents; wife committed to private asylum, 1758; Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (York 1759; Dodsley 1760 [half issue for sale]), bringing overnight fame though Dr. Johnson was to say, ‘Nothing odd will do long. Tristram Shandy did not last’; flirtation with Catherine Fourmantel, singer [‘dear Jenny’]. moved to London; painted by Reynolds; invited to court; 2nd ed. of Vols. 1 & 2; acquired third living at St. Michael’s Church, Coxwold, Yorkshire and settled in the house he called “Shandy Hall” (North Yorkshire), from 1760 to his death; issued the Sermons of Mr Yorick (1760), sometime styled scandal-making; 4 vols. of Tristram in 1761; voice affected in 1762; went with wife and dg. for France, Toulouse & Montpelier until 1764; returned alone to England; published vols. 7 & 8; returned to France and 8 months tour of France and Italy, from late 1765; lived at Shandy Hall, Coxwold; |

| A Sentimental Journey through France and Italy (1768); Yorick’s Sermons, vols. 2&3 (1766) [The Sermons of Mr Yorick, 7 vols. (1760-69)]. fell in love with Elizabeth Draper, young wife of East India official, 1767; Letters from Yorick to Eliza (1773), reflecting a platonic passion, written on her enforced departure for India; d. of pleurisy; reputed to have neglected his mother’s needs when in she was Peter’s Prison for debts - hence Byron, ‘I am as bad as that dog Sterne, who preferred whining over “a dead ass to relieving a living mother”’ (Journal); his body was grave-robbed, recognised at a Cambridge lecture and afterwards re-interred; he is considered to have been influenced by Cervantes, Rabelais, Sir Thomas Browne Robert Burton and John Locke - and called the Essay Concerning Understanding by the last-named ‘a history-book ... of what passes in man’s own mind’; the “Journal to Eliza”, found in manuscript, is now regularly printed with Sentimental Journey; an edition of the Letters published posthumously by his dg. Lydia; |

| his Brahmine’s Journal - another pseud. - pub. in 1904; the Letters were edited by Lewis Perry Curtis in 1935; a scholarly edition of the Sentimental Journey was issued by Gardner Stout in 1967; The Florida Edition of his Works was edited 8 vols. by Melvyn New, et al., during 1978-2009; the film-maker Michael Winterbottom has made homage to Tristram Shandy (A Cock and Bull Story, 2006). RR CAB ODNB PI JMC NCBE OCEL DIB DIW ODQ FDA OCIL |

|

|||

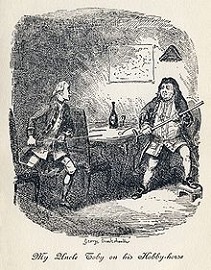

Left: “My Uncle Toby on his Hobby-horse” - George Cruikshank, ill. for Tristram Shandy. Right: Shandy Hall - photo by Eishiro Ito (2015). See further Cruuikshank illustrations scanned by Adam Cuerden at Wikipedia - online. |

[ top ]

Works| Tristram Shandy (selected edns. ) |

|

Note - chronology of Tristram Shandy: Volumes I-II appeared in Dec. 1759; Volumes III-IV in January 1762; Volumes V-VI in December 1762, Volumes VII-VIII in 1765, and Volume IX in 1767. |

| Other works (selected edns.) |

|

| [ top ] |

| Collected Works |

|

| [ top ] |

Bibliographical details

The Florida Edition of the Works of Laurence Sterne - Vol. 1: The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman [text], ed. Melvyn New & Joan New; Vol. 2: The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman [cont.], ed. Melyvn New & Joan New; Vol. 3: The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, gentleman [Notes], ed. Melvyn New, Richard A. Davies & W. G. Day (1984), [4], 572pp.; Vol. 4: The Sermons of Laurence Sterne [Text], ed. Melvyn New; Vol. 5: The sermons of Laurence Sterne [Notes], ed. Melvyn New; Vol. 6: A sentimental journey through France and Italy and Continuation of the Bramine’s Journal [Text & Notes], ed. Melvyn New & W. G. Day; Vol. 7: The Letters, Pt. 1, 1739-64, ed. Melvyn New & Peter de Voogd; Vol. 8: The Letters, Pt. 2, 1765-68, ed. Melvyn New & Peter de Voogd (2009), lx, 803pp., ill. [All vols. 24 cm.]

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

| Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies, Vol.II [of 2] (London & Dublin 1821), pp.576-58 - incls. a short life, with remarks on the Sterne’s apparent plagiarism of Sir Robert Burton. |

|

| see full copy in RICORSO > Library > Criticism > History > Legacy - via index or as attached. |

Samuel Taylor Coleridge spoke of the Tristram Shandy’s character in these terms: ‘the essence of which is a craving for sympathy in exact proportion to the oddity and unsympathisability of what he proposes.’ (Quoted in Paddy Bullard, ‘Motley Emblem of His Worm: Michael Winterbottom’s homage to Tristram Shandy’, review of A Cock and Bull Story, in See Times Literary Supplement, 10 Feb. 2006, p.18 [infra].)

|

Specimens of the Table-talk of the late Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. H. N. Coleridge (1835): |

|

|

“A Course of Lectures”, in Specimens of the Table-talk of the late Samuel Taylor Coleridge, ed. H. N. Coleridge (1835, &c.) |

|

| Sterne |

|

| [...] |

|

|

|

Q.pp.; available at Gutenberg Project - online. |

W. M. Thackeray: ‘He is always looking on my face, watching the effect, uncertain whether I think him an imposter or not.’ (Quoted in David Nokes, review of The Florida Edition of the Works of Laurence Sterne, Vols. 7 & 8 [being the Letters], in Times Literary Supplement, 21 Aug. 2009.)

Arthur Clery, Irish Essays (1919), ‘To call Sterne an Irishman is the mere pedantry of birth registration.’ (in The Field Day Anthology, gen. ed. Seamus Deane (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 2, p.1006).

Christopher Ricks, ed., Tristram Shandy (Penguin, 1967), Introduction: Ricks cites Swift sentence in the first of the Drapier’s Letters: ‘Read this Paper with the utmost Attention, or get it read to you by others’, going on to speak of ‘the old story in the jest books, where a templar leaves a note in the key-hole, directing the finder, if he cannot read it, to carry it to the stationer at the gate, who will read it for him.’ (Quoted in John Ferriar, Illustrations of Sterne, 1798; 2nd edn. 1812). Ricks goes on to speak of ‘that comic illogicality [as being] expanded in a thousand ways’ and later notes that Samuel Beckett is an admirer of Sterne. Ricks speaks of Beckett as being influenced by Sterne and cites Beckett’s quoting with relish Augustine’s saying about the two thieves (‘Do not despair, one of the thieves was saved; do not presume, one of the thieves was damned’, continuing: ‘Admittedly those words speak of a world very different from Sterne’s and if Beckett were not an important heir of Sterne it would be altogether far-fetched to quote them’, and goes on to apply them to the condition of the novel as Sterne found, and amended it ‘at a moment in history when literature, particularly the novel, was becoming tempted to presume.’ ( Tristram Shandy, 1967, p.7.) Ricks goes on to consider Beckett’s use of the French Catholic theologians per se, remarking on his interest in the theology of pre-natal baptism that the tone of such parodies is affectionate. The locus classicus is where the eighteenth c. Sorbonne authorities determine in French, at great length, pp.84-86, that one can inject baptismal water into the uterus - in spite of Aquinas’s untested assurance that in maternis uteris ... baptizari pussunt nullo modo’ [83]. In reflecting his, Sterne’s footnote ends, ‘O Thomas, Ó Thomas!’ This is indeed affectionate chiding, but the concluding jibe is more acerbic, where Shandy sends compliments to the doctors and suggests that the multitudinous homunculi can conveniently be pre-baptised ‘par le moyen d’une petite canulle [“squirt”, i.e. syringe] applied to the father before conception, sans faire aucune tort au père. Note the sentence in Tristram Shandy: ‘The minutest philosophers, who by the by, have the most enlarged understandings (their souls being inversely to their enquiries) show us incontestably that the Homunculus is created by the same hand [and is] as much and truly our fellow-creature as my Lord Chancellor of England.’ [36]. Bibliography incls. Walter Bagehot, ‘Sterne and Thackeray’, 1864; Wayne C Booth, ‘the Self-Conscious narrator in Comic Fiction before Tristram Shandy, PMLA, Vol. LXVII, 1952; Wilbur L. Cross, The Life and Times of Laurence Sterne (Yale UP 1923, 3rd ed.); John Ferriar, Illustrations of Sterne (1798; 2nd ed. 1812); Henri Fluchère, Laurence Sterne, de l’homme a l’oeuvre (Bibl. des idées, Paris 1961); Do., trans. & abridged by Barbara Bray as Laurence Sterne, From Tristram to Yorick (OUP 1965); D. W. Jefferson, ‘Tristram Shandy and the Tradition of Learned Wit’, Essays in Criticism, Vol. 1 (1951); adapted as ‘Tristram Shandy and His Tradition’ in From Dryden to Johnson: Pelican Guide to English Literature, ed. Boris Ford, vol. IV (1957); Hugh Kenner, Flaubert, Joyce and Beckett: The Stoic Comedians (W. H. Allen 1964); A. D. McKillop, The Early Masters of English Fiction (Kansas UP 1956; London: Constable 1962); John Traugott, Tristram Shandy’s World (California UP 1955); Ian Watt, The Rise of the Novel (London: Chatto & Windus 1957; Harmondsworth: Penguin 1963).

Christopher Ricks, Beckett’s Dying Words (OUP 1993), ‘The Irish Bull’ [Chap. 4], pp.153-203: Ricks traces the Irish Bull in literature and shows how it functions less as an unconscious solecism than a conscious trial of meaning at the limits of conventional language. Bibl. cites Brian Earls, ‘in his hospitable monograph’[acc. Ricks] on ‘Bulls, Blunders and Bloothers’, in Béaloideas, The Journal of the Folklore of Ireland Society (1988, I); see also John Collins’ poem, Scriptsapologia (1805), p.95, ‘Irish Blunder’.

A. N. Jeffares, Anglo-Irish Literature (1982), b. Clonmel, his father’s regt. broken; Dublin; Exeter; Derrylossary, nr. Annamoe in Wicklow where he had the escape with a millrace while the mill was going [‘The story is incredible, but known for truth in all that part of Ireland - where hundred of the Common People flocked to see me.’]. Carrickfergus; school in England, &c. ‘What he had gained from growing up in Ireland was the common heritage of many Anglo-Irish writers; genteel poverty, rich relatives, and talk as the cheapest means of entertainment. Mock-seriousness, serious mockery, the strain runs from Swift to Shaw, from Sterne to Joyce, even gentle Goldsmith shared this capacity for self-mockery. and the English read is often surprised at the way so many of them failed to allude to their mothers, or to do so in respectful terms. Perhaps they felt that their mother had failed, in choosing as husbands those who in turn failed to provide ... thus handing on a virtual duty of ambition to their sons. ... particular Anglo-Irish problem, of how ambition was to overcome genteel-poverty, was perennial (Jeffares, pp.53-57). NOTE, the episode at Annamoe is also cited in James Plunkett, The Gems She Wore (1972).

David Lodge writes, Sterne is a comic novelist who uses humour as a stay against misfortune, or a stay against death, which is what he tells us he is doing in Tristram Shandy. He says [Lodge paraphrasis, with particular reference to the dedication to Pitt], ‘I want to laugh, I want to amuse myself and you because I’m going to die, and therefore this is my protection. The play of the mind is my protection against the dying of the body’ (‘Laughing Matter; The Comic English Novel’, talk given by David Lodge and Malcolm Bradbury, 1991 Brighton International Festival in Moderna Sprak, Vol. lxxxvi, no. 1, 1992, p.7.)

Vincent Sherry, Joyce’s Ulysses (Cambridge UP 1994): ‘In The Life and Opinioins of Tristram Shandy Laurence Sterne concocts the most preposterous example of the story ever waiting to happen. An autobiography that purports to tell the tale of its author’s life ab ovo, its first volume ends twenty-three years before his birth, its seventh and last five years before. The prankishness of the compulsive digression combines its humour with a searching critique of the very material culture that creats the expectations Sterne is confounding through his inveterate detours and backtracking: namely, the culture of books, the medium of print, which imposes its linear and sequential mode as a paradigm of progressive reasoning, of consecutive happenings. One thing after another, the apparently militant continuum of print presents a fallacy or paradox that [45] Stern penetrates and dramatises with comic genius. His insights anticipate the premises of some post-structuralist linguistics, in particular the Derridean concept of deferral or différance. Here the serial arrangemet of language on the page projects meaning as a destination every awaited but constantly withheld, and this interval space locates the primary place for the actions of reading and writing. Thus the digression, veering off the single tract that rpint projects as its one axis of happening, captures the true experience of literature, of written letters, of books like Sterne’s. [Quotes “Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine ...”], &c., as infra.] The image of the bridegroom stepping forth to the consummation provides the ultimate prospect of fulfillment, but here appetite is satisfied through deferral, the via negativa of print. [...]’ (pp.45-46.)

Paddy Bullard, ‘Motley Emblem of His Worm: Michael Winterbottom’s homage to Tristram Shandy’, review of A Cock and Bull Story, in Times Literary Supplement (10 Feb. 2006), p.18: ‘Tristram Shandy is self-reflexive in two ways. It worries about its medium (its physical and formal bookishness), and it worries about the effectiveness of its many curious moves on the reader. Self-consciousness over the novel’s physical form shows up most obviously in Sterne’s flights from conventional typography. These include famously a page of solid black ink that marks the death of Yorick, an inserted sheet of bookbinder’s marbling (“motley emblem of my work”), a squiggly line to trace the flourish of Toby’s stick, and a blank bpage on which every reader can draw their own Widow Wadman. Sterne’s proposal is that they celebrate the diversity of imaginative response among his readers, and (with tongue in cheek) the “many opinions, transactions and truths which still lie mystically hid” under his tale. / One might add that tye make a happy point about the distances between life and art, and a rather grave one about the way that words tend to fail us. They anticipate the terminal literary impasse that Shandyism is supposed to defer. I have found that everyone who knows Tristram Shandy and who has yet to see A Cock and Bull Story is curious about how they are handled by Winterbottom. [...] If the director of A Cock and Bull Story is reluctant to reflect on his medium, he is still more bashful about his rhetorical designs on the audience. One source of humour in Tristram Shandy is the bumptiousness (“these heavenly emanations of wit and judgment”) with which Sterne discusses the felicity of his pen: “It governs me, - I govern not if”. He is always boasting about how unsuited the rashness of his writing is to the narrowness of the emotional mark at which he aims. The precision of Sterne’s attention to the incidental angle of Trim’s posture as he reads out Yorick’s sermon, or to the timing with which Trim drops his hat while announcing the death of Bobby, gives these sentimental strategies a comical, oratorical turn. But Sterne’s dearest wish is to have his fellow “fiddlers and painters” judge both his and their own work “by their eyes and ears, - admirable! - trusting to the passions excited in an air sung, or a story painted to the heart, - instead of measuring them by a quadrant”. This self-consciousness about emotional effect is connected with Sterne’s anxiety over posterity. Readers have always thought Tristram Shandy too odd to last, and Sterne’s. prayer that his book would swim safely down the gutter of time makes a grim choice between disposal and dispersal. [...] At the end of the film, Winterbottom transforms Sterne’s morbid obsession with literary fertility into a dream celebration of childbirth and parenthood. In so far as a Cock and Bull Story is self-reflexive, it allows no room for reflection on what its cinematic merits should be. Perhaps that is Winterbottom’s point, but a true Shandean should hope not.’

Peter Bradshaw, review of A Cock and Bull Story, in Guardian Weekly (27 Jan. 2006), p.21: ‘[...] an almost delirious atmosphere [...] making us breathe two different sorts of heady fume: postmodernism and celebrity’; ‘[...] the risk of studenty archness is high, and it is tricky to handle the comedy inherent in the fact that all this non-action and thwarted narrative is often quite boring [...] cheeky and flippant, the movie chimes nicvely with a book that, as Coogan puts it, was postmodern before there was anything to be postmodern about. [...] The film might just date more quickly than the book [...]’. see further under “Notes”, infra.]

[ top ]

Quotations| Digressions, incontestably, are the sunshine; - they are the life, the soul of reading; - take them out of this book for instance, - you might as well take the book along with them; - one cold eternal winter would reign in every page of it; restore them to the writer; - he steps forth like a bridegroom, - bids All hail; brings in variety, and forbids appetite to fail.’ (Tristram Shandy, ed. Graham Petrie, Harmondsworth: Penguin 1986, p.95; quoted in The Electronic Labyrinth, Virginia Univ. Electronic Text Centre [online]. |

| ‘ ‘tis a venereal case, cried my two scientific friends - ‘tis impossible, however, to be that, replied I - for I have had no commerce whatever with the sex, not even with my wife, added I, these fifteen years ... We will not reason about it, said the physician, but you must undergo a course of mercury.’ (Letter to Earl of Shelburne, recounting medical examination of the wound in his groin which Sterne later introduced as an episode in Bramine’s Journal; quoted in David Nokes, review of The Florida Edition of the Works, Vols. 7 & 8, in Times Literary Supplement, 21 Aug. 2009.) |

| ‘The truest respect which you can pay to the reader’s understanding, is to halve this matter amicably, and leave him something to imagine, in his turn, as well as yourself. For my part, I am eternally paying him compliments of this kind, and do all that lies in my power to keep his imagination as busy as my own.’ (Tristram Shandy, Vol. II, Chap. 2; quoted in Brigid Brophy, review of Colin MacCabe, James Joyce and the Revolution of the Word, in London Review of Books, 21 Feb. 1980, pp.8-9 - available online.) |

| ‘Gravity, a mysterious carriage of the body to conceal the defects of the mind.’ - Sterne; quoted in Ezra Pound, The ABC of Reading (1934; Faber Edn. 1991, p.13.) |

[ top ]

| Tristram Shandy (Reading notes: BS) |

|

| Note: 17 allusions to handkerchief detected by Google Books in Tristram Shandy - e.g., |

|

|

| —Google - search term <handkerchief> - online; accessed 03.06.2023. |

[ top ]

Time & Fiction (Tristram Shandy): ‘I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelve-month; and having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume - and no further than to my first days of life - ‘tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out; so that instead of advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what I have been doing at it - on the contrary, I am just thrown so many back - was every day of my life to be as busy as this - And why not? - and the transactions and opinions of it to take up as much description - And for what reason should they be cut short - as at this rate I should just live 364 times faster than I write - It must follow, an’ please your worships, that the more I write, the more I shall have to write - and consequently, the more your worships read, the more your worships will have to read. / Will this be good for your worships’ eyes? / It will do well for mine; and, was it not that my OPINIONS will be the death of me, I perceive I shall lead a fine life of it out of this self-same life of mine; or, in other words, shall lead a couple of fine lives together.’ [Vol. IV, chap. 13; p.286].

Walter Shandy: ‘I am convinced, Yorick, continued my father, half-reading and half-discoursing, that there is a North-west passage to the intellectual world; and that the soul of man has shorter ways of going to work, in furnishing itself with knowledge and instruction, than we generally take with ... the whole entirely depends, added my father, in a low voice, upon the auxiliary verbs, Mr Yorick.’ [394]. A man’s body and his mind, with the utmost reverence to both I speak it, are exactly like a jerkin, and a jerkin’s lining; rumple the one - you rumple the other.’ [174]. ‘The gift of ratiocination and making syllogisms - I mean in man - for in superior classes of beings, such as angles and spirits, - ‘tis all done, may by please your worships, as they tell me, by INTUITION; - and beings inferior, as your worships all know, - syllogise by their noses [242]. ‘That of all the several ways of beginning a book which are now in practice throughout the world, I am confident my own way of doing it is the best - I’m sure it is the most religious - for I begin with writing the first sentence - and trusting to Almighty God for the second’ [516]. ‘what has this book done more than the Legation of Moses, or the Tale of a Tub, that it may not swim down the gutter of Time along with them?’ [582]. ‘[Mrs Shandy never refused] her assent and consent to any proposition my father laid before her, merely because she did not understand it, or had no ideas to the primal word or term of art upon which the tenet or proposition rolled. She contented herself with doing all that her godfathers and godmothers promised for her - but no more; and so would go on using a hard word twenty years together - and replying, to it too, without giving herself any trouble to enquire about it.’ [[582]. Mr Shandy, consoling uncle Toby in the matter of Widow Wadman, ‘That provision should be made for continuing the race of so great, so exalted and godlike a Being as man - I am far from denying ... that it should be done by means of a passion which bends down the faculties and turns all the wisdom, contemplations, and operations of the soul backwards - a passion, my dear [addressing his wife], which couples and equals wise men with fools, and made us come out of our caverns and hiding places more like satyrs and fourfooted beasts than men./I know it will be said ... that in itself, and simply taken - like hunger, or thirst, or sleep - ‘tis an affair neither good or bad - or shameful or otherwise. Why then did the delicacy of Diogenes and Plato so recalcitrate against it? and wherefore, when we go about to make and plant a man, do we put out the candle? and for what reason is it, For what reason is it, the parts thereof - the congredients - the preparations - the instruments, and whatever serves thereto, are so held as to be conveyed to a cleanly mind by no language, translation, or periphrasis whatever?’ [613-14.]

Shandean Pessimism: Sterne makes Mr Shandy cite classical pessimism, ‘The Thracians wept when a child was born’ - (‘and we were very near to it’, quoth my uncle Toby) - ‘and feasted and made merry when a man went out of the world; and with reason ..’ [351]. ‘How finely we argue upon mistaken facts!’ [316]

Citations: Sterne as Irish tradition by Donn Byrne, and claimed as Irish in CABINET. Justin McCarthy. Irish Literature (1904), gives extracts from Tristram Shandy, and ‘Bon Mots’. Oxford Dictionary Quotations has 43 Sterne items.

Celibacy defended [Trims flourish of his stick] said more for celibacy [than] a thousand of my father’s most subtle syllogisms.’ [Mrs Shandy during the conception of Tristram:] ‘Pray, my dear, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?’ [Tristram as narrator:] ‘Here are two roads, a dirty one and a clean one, - which shall we take?’

What a Misfortune: ‘It is a terrible misfortune for this same book of mine, but more so for the Republic of letters; - so that my own is quite swallowed up in the consideration of it, - that this self-same vile pruriency for fresh adventures in all things, has got so strongly into our habits and humours - and so wholly intent are we upon satisfying the impatience of our concupiscence that way, - that nothing but the gross and more carnal parts of the composition will go down; - the subtle hints and sly communications of science fly off, like spirits upwards; - the more heavy moral escapes downwards; and both the one and the other are as much lost to the world, as if they were still left in the bottom of the ink-horn.’ (The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, 1759-67; ed. Graham Petrie, Penguin 1967, p.84.)

[ top ]

References

Dictionary of National Biography: after some years wandering sent to school in Halifax; left penniless; sent to Cambridge by cousin, Richard; sizar, etc. matriculated 1735; MA 1740; curate of Buckden; vicar of Sutton, 1738; first used epithet ‘sentimental’ in letter, 1740; obtained Stillington adjoining Sutton by wife’s influence, 1743; chaplain to 4th earl of Aboyne; interested in local private enclosure acts, 1756, 66; troubled by mother’s demands for money, and said to have let starve; interested in music; participates in Hall-Stevenson’s ‘Demoniacks’ orgies; satirised York lawyer as Trim in sketch (A Political Romance addressed to - Esq. of York [rare], first publ 1769); unfaithful to wife, who became insane; flirtation with Madame Fourmantelle; Tristram denounced in York on account of recognisable characters incl. Dr. John Burton; Warburton unavailing effort to restrain his obscenity; pamphlets against him, 1760-61; called house at Coxwold Shandy Hall; preached at Foundling Hosp. London, 1761; vols. v and vi of Tristram issued for him by Becket, and ded. to Lord Spencer; entertained by Fox at St Germain; left wife and dg. at Montauban by their wish; preached at English embassy in Paris, seeing much of Wilkes; painted by Gainsborough at Bath, 1765; met Smollett in Naples (‘Smellfungus’); book ix of Tristram ded. Chatham; Voltaire among subscribers to Sermons, vols. iii and iv; met Mrs Eliza Draper [q.v.] at house of Sir William James in London, Dec. 1766; kept journal, The Bramine’s Journal, after her departure (MS BML), Apr. to Aug. 1767; body sold to Dr Collignon, skeleton preserved at Cambridge; no will, died insolvent; wife and dg. salvaged by collections made by Hall-Stevenson and Mrs Draper; publication of letters to Mrs Draper threatened by widow; letters published by dg., Madame Medalle, and authorised by Mrs Draper, 1775; The Letters from Eliza to Yorick (1775) and Letters supposed to have been written by Yorick and Eliza (1779), are both forgeries; other forgeries incl. John Carr’s 3rd vol. of Tristram Shandy (1760); J. Hall-Stevenson’s continuation of Sentimental Journey (1769) [but note Margaret Drabble, ed., Oxford Companion of English Literature (OUP: 1985), by ‘Eugenius’, long incorrectly assumed to be Hall-Stevenson, see Note infra]. Richard Griffith’s Posthumous Works of a late Celebrated Genius (1770; included in first collected ed.); his works include many literary thefts, notably the scheme which resembles John Dunstan’s A Voyage round the World ... the rare adventure of Don Kainophilus (?1720); orig. style; first collective ed. of Tristram Shandy (1767), last (1779); Sermons reissued collectively, first 1775, last 1787; Sentimental Journey, with plates (1792); first collective ed. of works (without letters (Dublin 1779); best early ed. (with letters and Hogarth plates), 1780; another edited by Dr. J. O. Browne, with newly recovered correspondence, 1783.

Query: ODNB calls Archb. Sterne his grandfather (d.1683); DIB reports that he was sent to Cambridge by a cousin. See also Richard Ryan, Biographia Hibernica: Irish Worthies (1821), Vol. II, pp.576-78.

Charles A. Read, The Cabinet of Irish Literature (London, Glasgow, Dublin, Belfast & Edinburgh: Blackie & Son [1876-78]); selects passages from Tristram Shandy and Sentimental Journey, the same as later in Irish Literature (1904) [infra], his mother joined her husband at Clonmel shortly after his posting, and Laurence was born there soon after; his own narrative has the ‘household decamp with bag and baggage for Dublin’ when the Regt. is reformed; sent to school 1722 [sic]. noted as a genius by his teacher; sent to Cambridge by cousin; went to York, to Dr Jacques Sterne, after, and found a living, Sutton [sic brevis]. quarrelled with the doctor because he would not ‘write paragraphs’ in the newspaper for him, a party man, ‘which I was not’; at Stillington ‘books, painting, fiddling, and shooting were my amusements’; house in York, 1760; curacy of Coxwold, 1760; letters to his beloved daughter [Dictionary of National Biography shows that several other children were stillborn.] d. 18 March, Bond St. WORKS, The Case of Elijah and the Widow of Zarepphath Considered, sermon (1747); The Abuses of Conscience, sermon (1750); Tristram Shandy, i, ii (1959); iii, iv (1761); v, vi (1795) [err.]. vii, viii (1765); ix (1767); Sermons, i, ii (1760); iii, iv, v, vi (1766) [?ERR]. A Sentimental Journey (1768). Leigh Hunt, ‘If I were requested to name the book of all others which combined wit and humour under their highest appearance of levity with the profoundest wisdom, it would be Tristram Shandy; Horace Walpole, ‘At present nothing is talked of, nothing admired, but what I call help calling a very insipid and tedious performance. It is a kind of novel called The Life &c.’ Hazlitt, [In his father and Uncle Toby] ‘he has managed to oppose with equal felicity and originality purse intellect and pure good nature’; further, ‘the story of Le Fevre is perhaps the finest in the English language’; ‘of [Toby’s] bowling green, his sieges, his amours, who would think anything amiss?’. Speaks of Widow Wadman and her determined siege of Toby. Garrick’s epitaph, ‘Shall pride a heap of sculptured marble raise, / Some worthless, unmourn’d, titled fool to praise; / And shall we not by one poor grave-stone learn / Where genius, wit, and humour sleep with Sterne?’

Justin McCarthy, gen. ed., Irish Literature (Washington: University of America 1904); selects the same passages from Tristram Shandy as in Cabinet [supra], viz., ‘Widow Wadman’s Eye’, and ‘Alas, poor Yorick!’. The same biographical narrative is repeated, but an add. bibliographical item is added in citing Complete Works, with life (Stothard and Thurston 1808). Three bon mots include Garrick answering Sterne’s view that husbands who mistreat wives should be burnt down, ‘If you thing so, I hope your house is insured’; another by Sterne about serving books as people do lords, ‘learn their titles and brag of their acquaintance’, and a third aimed against an anti-clerical speaker.

[ top ]

Margaret Drabble, ed., Oxford Companion of English Literature (OUP 1985) [OCEL]. note that the entry on Sterne equates ‘Eugenius’ with Hall-Stevenson, implying [‘probably model for’] that he is a character. Similarly under Sentimental Journey, OCEL refers to a continuation of the journal by ‘Eugenius’, long incorrectly assumed to be Sterne’s old friend Hall-Stevenson [as in ODNB, supra]. Concise ODNB (1992) repeats the identification of Hall-Stevenson and Eugenius on the same paraphrastic principle. Under Stevenson-Hall, it is said that he was fr. of Sterne at Jesus Coll., assumed wife’s surname, inherit Skelton Castle (‘Crazy Castle’), Yorkshire, formed cub of Demoniacks, and entertained Sterne there; Eugenius in Sterne’s works; imitated Tristram, and wrote a continuation of A Sentimental Journey (1769); verse pamphlets, and Crazy Tales (1762, rep. priv. 1894); works collected 1795. OCEL lists him under Hall, orig. of Eugenius in Tristram and Sentimental; squire of Skelton Castle, nr. Saltburn-by-the-Sea, Yorkshire; ‘the Demoniacs’ [sic]. wrote Fables for Grown Gentleman (1761); Crazy Tales (1762), and some indecent verse satires to his notion of French fabliaux; not author of A Sentimental Journey Continued (1796); his works edited carefully but anonymously in 1795.

A. N. Jeffares & Peter Van de Kamp, eds., Irish Literature: The Eighteenth Century - An Annotated Anthology (Dublin/Oregon: Irish Academic Press 2006) selects extracts from Tristram Shandy [198] and A Sentimental journey Through France and Italy [202]. Cites Also Journal to Eliza (1904), not found in COPAC.

Belfast Public Library holds Tristram Shandy and Sentimental Journey, mod. eds.; also The Sermons of Mr. Yorick (1766); Works, 8 vols. (1794).

Eric Stevens Books (1992) lists The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, 3 vols. (T. Caddell 1794) [£12].

[ top ]

Notes

Irish writer? excepting notably A. N. Jeffares Anglo-Irish Literature (Macmillan 1982), Irish literary histories generally do not mention Sterne (viz., Deane, A Short History of Irish Literature, 1986), though dictionaries of biography do (viz., Harry Boylan, Dictionary of Irish Biography, 1988.)

Portraits by Reynolds, and a copy of one of these by Robert West (see Anne Stewart, National Portrait Collection, 1968). [See also Gainsborough, infra.] Lord Byron damaged his reputation by calling him a miserly and undutiful son; Thackeray wrote of ‘foul satyr’s eyes’ staring out of his prose; Leavis called Tristram Shandy nasty and trifling. See also, Laurence Sterne as ‘Tristram Shandy bowing to death’ by Thomas Peach, oil, held at Jesus Coll., Cambridge.

Sarsfield Connection: Sterne tells in Tristram Shandy that Uncle Toby and Corporal Trim were at the Siege of Limerick in ‘a marshy country ... surrounded by the Shannon’ [392]. it is thus curious that Toby got his wound at Landen [612] - where Patrick Sarsfield died fighting in the Irish Brigade on the other side.

Source of Shandy?: John Arbuthnot, Queen Anne’s physician and the friend of Jonathan Swift, wrote a history of the youth and education of Martin Scriblerus which, according to Carl Van Doren, Laurence Sterne ‘later pilfered from [...] for his history of Tristram Shandy’. (See Van Doren, intro., Portable Swift, 1948; Penguin Edn. 1977, p.24.)

Yorick/Yerrick: Note that one Richard Yerrick was bishop of London in 1769, when he ordained Samuel Parr, Burke’s sometime correspondent.

A Cock and Bull Story (2006): the film-maker Michael Winterbottom has made homage to Tristram Shandy, with Steve Coogan and Rob Brydon playing themselves playing Shandy and Uncle Toby while Jeremy Northam and James Fleet play the director and producer; Gillian Anderson plays herself helicoptered in to play Widow Wadman, while Kelly Macdonald is Coogan’s partner, and Naomie Harris plays the on-set runner Jennie, with whom he flirts dangerously. (Peter Bradshaw, review, in Guardian Weekly, 27 Jan. 2006, p.21; see supra.)

[ top ]