|

Hugh Quigley [Rev.]

Life

1818-1883; b. Dec. 1819, in Tulla, Clare; ed. at local hedge-school [taught by Master Walsh, nick-named Sean Cam/Shawn Kaum] and a classical school in Killaloe run by a certain Master Madden; worked with Ordnance Survey, Dublin; entered Maynooth Seminary on scholarship by examination, but refused the Oath of Allegiance to the Crown required at St. Patrick’s Seminary, Maynooth, and transferred to St. Mary’s [Seminary], Youghal; completed doctorate at La Sapienza Univ. in Rome [but see Clare People - infra]; ordained in Glasgow; ministered in Yorkshire and returned to Ireland where he tended to famine victims and participated in Young Ireland politics, 1847;

migrated to America on the invitation of Bishop Hughes (NY) in 1849; took legal action against anti-Catholic ‘nativism’ in schools in New York State; missionary to Chippewa Indians around Lake Superior; issued novels The Cross and the Shamrock (Boston 1853), a novel counselling Catholics on the keeping the faith in America; and [anon,] Prophet of the Ruined Abbey (Dublin 1863), as well as another set in Co. Clare in 1830s-40s and dealing with agrarian unrest and future revolution; encountered ecclesiastic opposition and served unofficially among Union soldiers in the Civil War; worked with Catholic miners and farmers settled in Erin Prairie;

| Note: a passage in The Cross and the Shamrock shows a priest bearing Quigley's name on board a ship to America which was stricken with fever: ‘Sad and impressive was the scene when the Rev. H. O’Q——, a young Irish priest on board, in the middle hold of the ship, where O’Clery had been removed by order of the captain, called on the six hundred surviving passengers to kneel while he was administering the rites of the church to the benefactor of them all. ...’ [See infra.] |

moved to Wisconsin, pastor in 1868, then Colorado before settling in San Francisco, 1878-81; working with miners at Eureka; published The Irish Race in California (1878), encouraging Irish migrants to settle in that state; suffered declining health and returned to Albany, NY; d. 30 April 1883, in Albany, with friends and bur. St. Mary’s, Troy; there is a biography by Johanna Schwartz. DIW IF SUTH RIA

[ There is an entry by Deirdre Bryan in Dictionary of Irish Biography (RIA) - online. ]

[ top ]

Works

| Novels |

- The Cross and the Shamrock; or, How to Defend the Faith. An Irish-American Catholic Tale of Real Life, descriptive of the temptations, sufferings, trials and triumphs of the children of St Patrick in the great republic of Washington. A book for the entertainment and special instruction of the atholic male and female servants of the United States (Boston, Patrick Donahoe [1853]) [see details].

- The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey, or, A Glance of the Future of Ireland: a narrative founded on the ancient ‘Prophecies of Culmkill’, and on other predictions and popular traditions (NY: E. Dunigan and Brother 1855), 293pp.; Do. [another edn.] (Dublin: Duffy 1863), vi, 247pp.[see details].

- Profit and Loss: A Story of the Life of the Genteel Irish-American, illustrative of Godless Education (NY: T O’Kane 1873), xi, 458pp. [serialised 1872].

|

| In translation |

- Le prophète du monastère ruiné; ou, L'avenir de l'Irlande, tr. de l'anglais avec l'autorisation des éditeurs par M. William O’Gorman [pseud.] (Paris: Putois-Cretté 1859) [trans. of The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey, ].

|

| Miscellaneous |

- The Irish Race in California and on the Pacific Coast: with an Introductory Historical Dissertation on the Principal Races of Mankind, and a Vocabulary of Ancient and Modern Irish Family Names (SF: A. Roman & Co. 1878); Do. [facs. edn.] (Whitefish, MT: Kessinger 2010), 576pp.

|

Bibliographical details

The Cross and the Shamrock; or, How to Defend the Faith. An Irish-American Catholic Tale of Real Life, descriptive of the temptations, sufferings, trials and triumphs of the children of St Patrick in the great republic of Washington. A book for the entertainment and special instruction of the atholic male and female servants of the United States (Boston, Patrick Donahoe [1853]); Do. [...[ by the author of The Cross and the Shamrock (Dublin: James Duffy & Sons [c.1890]), 255pp. [dated from pub. list bound in at end], and Do., as The Cross and Shamrock [... &c.] By a Missionary Priest [new edn.] (Dublin: James Duffy & Co. [c.1900]),

xvi, 240pp. Internet: The Boston edition of 1953 is available at Gutenberg Project [online] with a link from Liverpool U. [online].

THE

CROSS AND THE SHAMROCK,

OR,

HOW TO DEFEND THE FAITH.

AN

IRISH-AMERICAN CATHOLIC TALE

OF REAL LIFE,

DESCRIPTIVE OF THE

TEMPTATIONS, SUFFERINGS, TRIALS, AND TRIUMPHS

OF THE

CHILDREN OF ST. PATRICK

IN THE

GREAT REPUBLIC OF WASHINGTON.

A BOOK

FOR THE ENTERTAINMENT AND SPECIAL INSTRUCTIONS OF

THE CATHOLIC MALE AND FEMALE SERVANTS OF THE UNITED STATES.

WRITTEN BY

A MISSIONARY PRIEST.

BOSTON:

PATRICK DONAHOE,

3 FRANKLIN STREET.

1853 |

|

| See Dedication & Preface under Quotations - infra. |

The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey, or, A Glance of the Future of Ireland: a narrative founded on the ancient ‘Prophecies of Culmkill’, and on other predictions and popular traditions (NY: E. Dunigan and Brother 1855), 293pp.; Do. [another edn.] (Boston: P. Donaho[e] 1860), 293pp.; Do. [another edn.] (Dublin: Duffy [printed by Moore and Murphy] 1863), vi, [2], 247 [1]p. Note: COPAC cites Preface dated New York, Aug. 1855 and makes reference to a listing in NUC National Union Catalogue [NUC/USA] which cites an 1854 edition. [Ref. Brown, item 1440.] Copyright notice: Entered according to act of Congress in the year 1854, by JAMES B. KIRKER, In the Clerk's Office of tho District Court of the United States, for the Southern District of New York. [t.p. verso.]

Dedication: To His Imperial Majesty, Napoleon the Third, Who has been Elevated to the Throne o the Caesars by the Votes of Seven Millions of His Countrymen; Who has been Applauded by the Unanimous Voice of All Civilized Nations as the The Saviour of France; and Who had had Addressed to Him the Petitions and Anxious Entreaties of Ten Millions of Irishmen in Both Hemispheres, as the Expected Conqueror of England, True Liberator of Ireland, the Following Pages are Respectfully Inscribed,

BY HIS OBEDIENT SERVANT,

THE AUTHOR.

New York, November 20th, 1854.

| Index of works available at Internet Archive with inks supplied by Clare County Library |

The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey; or, A Glance of the Future of Ireland: a narrative founded on the ancient “Prophecies of Culmkill” and on other predictions and popular traditions among the Irish

by Hugh Quigley.

Published in 1855, E. Dunigan and Brother (New York)

Statement: By the author of “The cross and the shamrock” ..

Pagination: 293pp.

Subject: Irish in literature

Available at Internet Archive |

C

L

A

R

E

L

I

B |

| Copy held in University of California Libraries (sometime in San Diego). |

|

[ top ]

Quotations

| Dedication & Preface to The Cross and the Shamrock (Boston 1853) |

| Dedication |

To the faithful Irish-American Catholic citizens of the whole Union, and especially to the working portion of them, on account of their piety, their liberality, their patriotism, and their steady loyalty to the virtues symbolized by the “Cross and the Shamrock,"—on account of their attachment to the land of St. Patrick, and to the religion of her patriot princes and martyrs,—this work, written for their encouragement and instruction, is respectfully inscribed by |

Their humble servant,

And devoted friend and fellow-citizen,

|

The Author

|

| Preface |

‘There are moments when every citizen who feels that he can say something promotive of the welfare of his countrymen and of advantage to his country is authorized to give public utterance to his sentiments, how humble soever he may be.’—Letter of Archbishop Hughes on the Madiai, February, 1853.

‘There may be, in public opinion, an Inquisition a thousand times more galling to the soul than the gloomy prison or the weight of chains.’—National Democrat, March, 1853).

|

When we know this to be literally true, and find our poor, neglected, and uninstructed brethren in danger accordingly, how can any thing that can be said, written, or done, to alleviate their condition, or to remove prejudice from the public mind, be counted a work of supererogation?

2d. The corruption of the cheap trash literature, that is now ordinarily supplied for the amusement and instruction of the American people,—and that threatens to uproot and annihilate all the notions of virtue and morals that remain, in spite of sectarianism,—calls for some antidote, some remedy. In every rail car, omnibus, stage coach, steamboat, or canal packet, publications, containing the most poisonous principles and destructive errors, are presented to, and are purchased by, passengers of both sexes, whose minds, like the appetites of hungry animals, will take to eating the filthiest stuff, rather than want food for rumination. It is for the philanthropists of the present day, and for those who are paid for making such inquiries, to trace the connection between the roués of your cities, your Bloomer women, your spiritual rappers, and other countless extravagances of a diseased public mind, and between the abominable publications to which we allude.

3d. Our people are not generally great readers of the trashy newspapers of the day; and in this respect they show their good sense, or at least have happened on good luck: it is therefore our duty to supply them with cheap and amusing literature, to entertain them during the few hours they are disengaged from work. And what reading can afford the Irish Catholic greater pleasure than any work, however imperfect, having for its end the exaltation and defence of his glorious old faith, and the vindication of his native land—his beloved “Erin-go-bragh”? Impress on his susceptible mind the honor and advantage of defence and fidelity to the Cross and the Shamrock, and you give him two ideas that will come to his aid in most of his actions through life. We are ashamed here of the cross of Christ, when we see it continually dishonored and trampled on by heretics and modern pagans, in their scramble for money and pleasures. On the other hand, the poverty, humiliation, and rags of old Erin, of the kings, saints, and martyrs, scandalize us; and from these two false notions the degradation and apostasy of many Irishmen commence. Hence they no sooner land on the shores of America than they endeavor to clip the musical and rich brogue of fatherland, to make room for the bastard barbarisms and vulgar slang of Yankeedom. The remainder of the course of the apostate is easily traced, till, ashamed of creed and country, he ends by being ashamed of his Creator and Redeemer, and barters the inheritance of heaven for the miserable and short enjoyments of this earth.

A fourth, and a leading motive in the publication of this work, is to record the manly defences which the people among whom the author lives have made of the creed of their fathers, and to enable them to refute, in a simple, practical manner, for the edification of their opponents, the many objections proposed to them about the faith. By placing a copy of this work in the hands of every head of a family in the congregation in which he presides, the author thinks he will have done something towards the salvation of that parent and his house, by showing him how he may educate his children, and save them from those subtle snares laid to rob them and him of happiness here and hereafter; for, without true religion and virtue, there is neither enjoyment nor happiness even in this world.

But are the principles sound, and the estimate he has formed of American character and the conduct and motives of the sectarian parsons correct? There may be, and undoubtedly there is, great variety in American character; and, so far, what may be true of the people of one state or county, may not at all be applicable to those of the rest; but as far as regards sectarianism and its slanders of the church, and the low character, intellectually and morally, of the parsons, ministers, dominies, and preachers, with few honorable exceptions, it may be said, in the words of the poet,—

‘They are all chips of the same block;’ and the description in the following pages of their attempts to proselytize, seduce, and corrupt, is not at all exaggerated, as thousands of candid American Protestants can testify. Perhaps the sectarian dominies do not see the sad consequences that are infallibly produced on the minds of their hearers, after they come to detect the frauds and falsehoods which the parsons inculcate on them when children; but they are in the cause, and morally responsible for that doubt, irreligion, and downright infidelity which are the well-known characteristics of the male and female youth of our great country, and which threaten such disastrous consequences to society.

Yes, dominies, you are responsible for all the extravagances of modern times, for the irreparable loss to virtue and society of the noble youth of your country. You hate the church of God because she is a witness against you. The priest, the nun, and the recluse are objects of your malice; for they are living examples of what you call impossible morals, and refuters of the code of low virtue you practise and preach. The faith of the Catholic laity, too, you endeavor to destroy, in order more securely to deceive your hearers, and to secure your children, your wives, and yourselves, that bread which you eat by the dissemination of error, contradiction, and contention, and which you are too lazy to “earn by the sweat of your brow.”

Finally. This work is submitted to the reader by one who will be well pleased if it affords the former any pleasure or amusement during one or two of such few hours of leisure as it took the latter to write it. Regarding style, method, and arrangement of the matter, the author has no apology to offer, except that the work has been written in great haste, and by one who, in five years, has not had a single entire day for recreation or unoccupied by severe missionary duty. Let not the critics forget this.

|

| Available at Gutenberg Project - online; accesssed 21.09.2023. |

| Chapter V: The O’Clerys |

The O’Clery family was an ancient and honored one in Ireland. Princes, chieftains, and warriors of the name were renowned before Charlemagne or Alfred ascended the throne, or before any of the petty princes of the heptarchy ruled over the barbarous Saxons. Like all the royal and noble houses of Europe, the O’Clerys, after ages of glory and prosperity, had their hour of decline and decay also. But it was a question whether the virtues of this renowned house were more brilliant or conspicuous in the zenith of its glory, or in its fallen or humbled state. The Irish church founded by Saint Patrick never wanted an O’Clery to adorn her sanctuary or to record her victories. The annals of the Four Masters will stand to the end of the world as a proud monument of the services rendered to the Irish church and to history by these illustrious annalists; and when the deeds of the most renowned knights and chieftains of this royal house shall have been obliterated by the merciless chisel of time, the authors of the Four Masters’ Annals will become only brighter among the shining stars that adorn the literary firmament of old Ireland.

The martyrology of the Irish church can attest the virtues of constancy and patriotism with which the O’Clerys bore their share of the wrongs of Erin and of her faithful sons. Whether or not the subjects of our narrative, the poor emigrant orphans, had any of this royal and noble blood flowing in their veins, is a thing that we cannot genealogically vouch. But that they were not degenerate sons of Erin, or faithless to their allegiance to the glorious old church of their fathers, we trust this history will amply demonstrate. At all events, the uncle of our hero, Paul O’Clery, held a very high station in the Irish hierarchy. Having, with eclat, finished his ecclesiastical and literary primary studies in the colleges of his native land, he subsequently repaired to Rome, where he won with distinction the title of “doctor in divinity and canon law,” and carried the first premium from many French, German, and even Italian competitors. Hence, soon after his return from abroad, on account of his learning, as well as his tried virtues, he was appointed the vicar general of the diocese of Kil——, a promotion which, far from exciting the envy, gained the unanimous approval, of the diocesan clergy. During the horrors of the general landlord persecution of the Irish Catholics, (for it is nothing else than a persecution of Catholics,) the O’Clerys found their name on the roll of the proscribed, and got notice to quit the homestead of their fathers. The principal cause for this proscription by the landlord was, that Dr. O’Clery, in the newspapers, exposed the system of cruel and barbarous extermination which took place on the extensive estates of Lord Mandemon—a gentleman who said he thought it far more honorable, as well as profitable, to have his princely estates in Munster tenanted by fat cattle than by Irish Papists. His lordship had also the mortification to learn that all the meat, money, and clothing he had employed for the last five years could not make one single sincere convert to his rich “law establishment.” When the “praties” were dear, and the crops failed, there were a few, to be sure, who would profess themselves ready to “ate the mate” on Friday; but as soon as plenty returned, the “new lights” went out, or returned to ask pardon of God, the priest, and the people; and Lord Mandemon and his soup were pitched to the “seventy-nine devils.” This failure, this result, so often before seen and felt, and so certain to follow, was, in his zeal for proselytism, attributed by his lordship to Dr. O’Clery’s zeal and learning. For, whenever or wherever he went among the peasantry to preach to them in their own sweet and loved dialect, the “jumpers, the new lights, and the soupers” disappeared like the locusts from Egypt when exorcised by the magic rod of Moses. Hence the hatred with which the O’Clerys were persecuted. Hence, also, the oath of Lord Mandemon, that he would never return to his home in England till every Papist on his estates was rooted out. This oath was kept by his lordship, probably the only true one he ever swore; for in less than a fortnight he fell a victim to the cholera, and expired on board the Princess Royal steamboat on her return to Liverpool.

Arthur O’Clery, father to the subject of our tale, sold out a second farm he held near Limerick, turned all his effects into money, bade adieu to his beloved brother, Dr. O’Clery, who was averse to his emigration, and, in the autumn, set sail from Liverpool for New York, in the ship Hottinguer. He had all his family with him: they were comfortably provided with all necessaries, and, besides, had one thousand pounds, in hard cash, to start with in the new world. They were not long out at sea, when, owing to the crowd on board, the lack of proper arrangements, and room, or ventillation, as well as on account of the cruelly of the inhuman captain, ship fever and cholera broke out on board.

The number of bodies consigned to the ocean from that unlucky vessel was from five to ten daily, and among the victims of the plague was Arthur O’Clery. He was the only one of the cabin passengers who was attacked by the epidemic, which, in the ardor of his charity, he contracted while attending on, and ministering to, the wants of the poor steerage passengers.

Sad and impressive was the scene when the Rev. H. O’Q——, a young Irish priest on board, in the middle hold of the ship, where O’Clery had been removed by order of the captain, called on the six hundred surviving passengers to kneel while he was administering the rites of the church to the benefactor of them all. Never was a call on the piety and faith of any number of men more cheerfully obeyed. Instantaneously that mixed, nondescript crowd—Irish, English, Scotch, Welsh, Dutch—Catholic, Protestant, infidel—fell on their knees, and, if they did not pray, they paid that outward homage to Religion which sometimes the most indifferent and irreligious cannot resist paying her. Infidelity is a great coward, as well as a false guide. In her hour of ease and satiety, she pretends to scorn the threats and judgments of the Most High, and, like Satan in his pandemonium, to make war on Heaven; but no sooner does the roaring of the thunderbolt shake the earth, or the vast abyss open its devouring throat to swallow her unhappy victims, than she hides her head in the caves of the earth, or, flying to some secure place, abandons her votaries to the forlorn hope of trusting to the weakness of their own minds for resources to extricate themselves from the evils that threaten them. It was so on board the ill-fated Hottinguer. Those who, under the influence of the security offered by the prosperous sailing of the few first days, were bold, independent, and defiant of danger, no sooner did they see their comrades thrown overboard, after a few hours’ sickness, than their hearts failed within them, their tone of defiance was turned into despair, their mockery of religion ceased, and that priest of God, whom they ridiculed, insulted, and despised for the first few days, was now respected, confided in, and regarded by them with sentiments bordering on religious homage.

Fervently did that priest, who thanked God that he was on hand, pray, not that God would restore him to his wife and children,—for all hope of recovery was now gone,—but that, in accordance with the anxious desire of the dying man, he should have the privilege of burial in a Christian, consecrated tomb.

“Pray, father,” said he, “that, if it be God’s holy will, I may be buried in a consecrated soil. It seems to me a sort of profanation, that the cruel fishes and those monsters of the deep, which we see leaping around the vessel, should devour my flesh, united with, and I hope sanctified now by, the flesh and blood of my Lord.”

The priest did pray, and the people joined in that impulsive prayer of faith, and that prayer was heard; for, though O’Clery breathed his last on board, and, by the captain’s orders, the sailors—poor fellows!—were standing around his berth, prepared, as soon as the last breath left him, to throw him overboard, yet he lingered for three days after; and they reached quarantine before that pure soul quitted its tenement of clay and winged its flight to heaven. The wife and her children had the body conveyed to shore and interred in the Catholic cemetery of New York, where a neat marble monument could be seen with these words inscribed:—

“Pray for the soul of Arthur O’Clery, whose body lies underneath. Requiescat in pace. Amen.”

It was thus that the O’Clerys were deprived of their good and virtuous father, and the widow of her husband; but this, as already has been partly seen, was but the beginning of their woes; for, after their arrival in New York, an individual, who, during the voyage, ingratiated himself with the family by his attention around the sick man’s bed, joined them at their lodgings. But in a few days they found him gone one morning, after their return from mass at Barclay Street Church, and with him the canvas bag, containing the thousand pounds in gold and Bank of England notes left by them in a trunk. Thus were six persons, strangers and destitute in a great city, reduced from competency to poverty at “one fell swoop” by the villany of a pretended friend and associate.

“O Lord, pity me! One misfortune never comes alone,” groaned the now poor and afflicted widow O’Clery, when she was informed by little Bridget that the “trunk was broke open,” and all the things ransacked “through and fro.”

She soon saw that all she had was gone, and concluded that Cunningham, as he was absent from breakfast contrary to his wont, must be the thief. The police got immediate notice; advertisements were issued, and rewards offered, and in a day or two after Cunningham was arrested; but as none of the money was found on his person, and as there was no direct evidence of his guilt, the magistrate discharged him. The articles of dress in her well-supplied wardrobe were detained, in payment of her board bill, by the hotel keeper where she lodged in New York; and with the few shillings that remained in her purse, she, with her children, took passage on one of the Hudson River boats, hoping to make out certain acquaintances of her husband, whom she heard were settled in the vicinity of T——. The rest has been already told—namely, how she took sick and died after great sufferings; how her children were left destitute, and next to naked; how they were now reduced to the rank of paupers, and secured within the precincts of the county house.

“Of all the things which we brought from home with us, we have nothing of value now left, Bridget,” said Paul, “but this silver crucifix, which belonged to my grandfather. Glory be to God. Let us be glad that this has been left,” said he, kissing it with religious affection. “This is all we have now left. Let us defend it.”

|

| Available at Gutenberg Project - online; accesssed 21.09.2023. |

[ top ]

| The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey; or, A Glance of the Future of Ireland (1855) |

| Preface |

The object of the following story is, in the first place, to save from oblivion and decay the legends and popular traditions on which it is principally founded, and which are here, as the author believes, for the first time, committed to print. Many an “Exile of Erin” will derive pleasure from reading, by the stove-side, during the long winter nights, and in the midst of his family, a Yew, even, of those tales, which, though in. the awkwardness of a foreign tongue, and but indifferently told at that, he cannot but recognize as some of those which he often listened to, at home, in the chimney-corner, by a fire of blazing turf!

The second, but not secondary aim of the author of this work is, to keep alive and kindle in the bosoms of the Irish Catholic people of this republic genuine sentiments of patriotism and religion, both of which are threatened with danger, on the one hand, from the treachery of a few bad Irishmen themselves, and on the other, from the arrogant assurance of a few fickle-minded spirits, who would persuade the Irish race of this great continent, to forget their country, their origin, their descent, their history, their traditions and bygone glories, which are nicknamed “Irishism,” and as the inevitable consequence, though this may not be intended, to forget their Religion! Has it come to this, that a few individuals, not numerous nor respectable enough to be accounted a school of philosophy, have had the infatuation, if not audacity, to call on us, the best Catholics in America, or the world, to obliterate all the venerable monuments of the pedigree of saints and kings from which we have sprung, and to amalgamate with the parvenu [7] nondescript breeds of the New World? Forget the land of our birth and our “Irishism,” indeed ! No, but, like the Jews, sitting by the banks of the Hudson, the St. Lawrence, and the Ohio, and all the other rivers from Oregon to Maine, and from the Gulf of Mexico to Hudson's Bay, let the Irish sing the songs of their Sion, and hand down to their latest posterity the reminiscences of Holy Ireland ! Attachment to the land of our nativity, so far from proving injurious to our religion or the progress of our faith, as is asserted, will have the contrary effect ; the experience of the Clergy in the Union going to show, that the man who denies his country, or is ashamed of its language, habits and traditions, is the first also to deny his God and his religion; while the most unfailing, if not the strongest tie that binds the heart of the Irish Celt to the Cross of Calvary, is made out of the green stems and leaves of “Erin's Immortal Shamrock!"

Nothing so much contributed to keep alive the faith, in the hearts of the exile people of God, as

[8] their frequent recollection of “Fatherland,” and the chanting of its sacred melodies ; and did not the Almighty himself wish to be called the God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, in order that the two sacred fires of patriotism and religion should blend and burn together on the same altar of the heart?

Some of these very men, who affect to be shocked at the “Irishism” of the Catholics, have, if we mistake not, given lectures to show how the Irish Catholics were a missionary race, chosen by God to be his agents in the regeneration of the modern world, and are they Jonas-like to shrink from the Heaven-appointed mission, and exchange the glorious ignominies of the cross and the mocked robe of the missionary, for the flesh-pots and “rich meats” of Babylon's table? If they should, and bending to the prejudices of a corrupt, godless people, they get discouraged at the high task proposed to them, an abyss of ignominious oblivion deeper than the ocean, and more noisome than the whale's stomach, will await them and [9] their descendants here and hereafter. Are the Irish Catholics, then, a missionary people, whose destiny it is to propagate the faith, and carry the knowledge of the cross and the science of salvation through the length and breadth of this vast country? If such be their high vocation, they ousrht not to blend with, but rather remain separate from, the people which they are ordained to regenerate or reform! But, if they become absorbed in the amalgam of races which form the population of these United States, and as a consequence adopt their prejudices and vices, their usefulness as missionaries is at an end, and instead of converting others they become themselves perverted.

This work is published, lastly, because the author would contribute his quota to the growing Catholic literature of the country ; and he feels it to be a work, not of supererogation but of charity, to supply, as far as in him lies, and though it were but in a single instance, an antidote against the literary poison, which, in the shape of tales [10] and stories, is daily thrust into the hands of our youth of both sexes.

To the critics the author has only to say, that he trusts he has avoided in the following story the numerous faults in its plot and machinery pointed out to him in their review of a former publication of his, for which favors he has labored under a deep debt of gratitude to them, and which he is prevented from personally acknowledging, only by his determination to continue still anonymous.

|

| pp.[5]-10; available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 23.04.2024. |

| |

| CONTENTS |

I-

II.

III.

IV.

V.

VI.

VII.

VIII.

IX.

X.

XI.

XII.

XIII.

XIV.

XV.

XVI.

XVII.

XVIII.

XIX.

XX.

XXI.

XXII.

XXIII.

XXIV.

XXV

XXVI

XXVII

XXVIII |

An Exile’s Return to his Native Land

A Rural Scene

Fraternal Affection

The Escape

“The Enchanted” Warrior”

The Counsels of the Great

The Expedition against the Rebels

The Captive

The Fate of the Fugitive

The Ambuscade

Dangerous Curiosity

Paudeen O’Rafferty’s Story

Going from the Smoke into The Fire

A Sample of English Justice

A Wild Scene of Nature

“The Laveragh Lynchagh” or, Long-haired Prince

The Hermit’s Novitiate

The Rapparees

The Captain renounces the Life of a Rapparee

and returns to France

Mao an ’Uller, or, the Eagle’s Son

A Child of Nature’s Sports and Pastimes

The Haunted Abbey

The Disclosure

The Departure of Brefni

Strange and Mysterious Incidents

The Treasure Seekers

The Renewal of Old Acquaintance

The Hermit Commemorates the Festival of St. Stephen, Protomartyr |

13

23

41

55

68

77

90

103

114

123

134

142

151

161

171

180

191

190

212

221

231

238

248

254

260

267

277

288 |

|

| |

| Chap. I: AN EXILE’S RETURN TO HIS NATIVE LAND. |

On a Sunday morning, in the month of May, in the reign of the third George, a year or two before the close of the war of American Independence, there appeared a stranger among the worshippers at the humble Catholic Chapel of Dungarvan, in the county of Waterford, Ireland. At what hour he entered this house of God on this delightful morning, or whether he took refuge within its peaceful precincts during the gloom of the previous night, cannot be now satisfactorily ascertained; but, certain it is, that the first living object which old widow Power, who lived near the chapel gate, saw on her going into the chapel, was a gentleman prostrate in prayer before the altar — and during the past forty years, the widow [14] never once failed to have her fifteen decades of the Rosany for the repose of her husband’s soul, said long before sunrise! The first impression of the pious widow Nora was, that it must be one of the clergy who was praying before the sanctuary at such an early hour, and with a due sense of the impropriety of distracting the fervent suppliant, she knelt down in the very porch of the church, and commenced counting her beads. But, when the glimmering twilight of dawn melted into the broad, morning glory of sunrise, it was evident that the stranger was not a clergyman. He was dressed in a suit of superfine blue-black broadcloth, consisting of a long-skirted dress or body coat, embroidered long vest reaching almost to the thighs, with deep lapelled pockets, and loose pantaloons strapped beneath a well turned and polished boot. A stock or tie of dark green velvet, fitting close to the neck, with a beaver hat, somewhat of a conical shape in the crown, and light buff buckskin gloves, completed his costume. His physical appearance was of rather a remarkable mould. He was about five feet eleven in height, of flush and sanguine complexion, firmly built, and apparently of great strength. His face was large and full. His mustachios on the upper lip, the only beard he wore, of a sandy hue, but thick and gracefully shaped. His forehead ample, rather than high, and surmounted by a crop of curling, dark chestnut hair. His eyes were not large, but extremely sharp [15] and penetrating; his nose rather prominent and slightly aquiline. His mouth seemed made more for giving utterance to quick, stern decrees, than for the graceful charms of persuasive eloquence. In a word, his beautifully arched eyebrows, his oval chin, and all the other prominent points of his figure, were in perfect keeping with the pleasing regularity of his features, and he could not fail, in any discerning society, to be complimented on being an “elegant gentleman,” or a “fine man,” according as the phraseology of different classes may term it.

The appearance of this stranger, remarkable though he was, kneeling at the rails of the sanctuary, did not create much curiosity among the worshippers at this humble temple of God, taught as they were to regard it as sinful to gaze or be distracted in the church, and wholly intent in offering their sincere homage to the Redeemer, whose real and personal, but mysterious presence, occupied their souls and rendered them, while sheltered under the same roof with their Creator, insensible to all created things! In the eye of true believers, all men, emperors, kings, princes, appear truly insignificant inthe presence of the Lord of Glory; and whilst Jesus Christ, the true Moses, is face to face with God “on the Holy Mount where his infinite love has detained him to make intercession for his people, they ought to lie prostrate at its foot in contrite prayer, to merit the [16] favor, or escape the wrath of the offended Jehovah! This was the custom of Christians of the time to which our pages refer, and it is the rule, and not the exception, to this day in Ireland, where, it must be confessed, many innovations of modern churches have not yet made much progress, and where the fashionable custom of “watching,” instead of praying, fasting and sacrifice, has not yet gained the ascendant as with the respectable and enlightened professors of “modern” Christianity, in their carpeted and well-cushioned meeting-houses. . Although our stranger was unobserved or unheeded by the humble occupants of the damp clay floor of St. Declan’s Church, he did not escape the observation of the two venerable clergymen who officiated at the three services of that Sunday. Having partaken of the most Holy Sacrament at the first Mass, he continued still unmoved in the same place during the second service, his mind apparently absorbed in his devotions. The third service at noon had now commenced; and at the Communion, when the senior pastor of the church, a man of venerable age and saintly appearance, begged of that large congregation, in a voice trembling with emotion, that they would offer up their prayers for the temporal and eternal welfare of his friend, Rev. Dr. O’Donnell, who was under sentence — unjust sentence — of death, in a neighboring county, the strong frame of the stranger was observed to tremble, the color left his manly cheek, [17] and he had to lean back to the wall for support, A thrill of horror, at this announcement, pervaded the congregation, for the Reverend victim of British persecution was well known to them all. He had served them for a time as curate, or vicaire, and his benevolent acts were familiar as household words at every fireside in the large parochial district of Dungarvan. Loud sobs and tears now burst from the large assemblage within and around the church. Even the aged pastor himself was carried away by the contagion of the common grief, and was obliged to go back to the vestry to recover his selfpossession. Now would be the time, thought the stranger, to raise this large body of men into action, and conduct them to the rescue of the convicted priest, or marshal them in array against the enemy of their country. Here was a chance that, in his plans for the freedom of the beloved land of his nativity, he often wished for. The influence of the officiating priest, he thought, would be of no avail to repress the manly passions that glowed within the bosoms of that great crowd. The blood rushed back to his face, he instinctively placed his hand on his hip, as if to grasp the sword that usually rested there, for he belonged to a regiment of French Chasseurs; when the angelic face of Father O’Healy now appeared returning from the vestry, and the chant of the “Dominus Vobiscum,” responded to by the choir, fell on his subdued ear. The piercing eye of the venerable [18] pastor now encountered that of this enthusiastic young man, who felt as if his very soul was read in that glance. His elevated feelings were brought down to the cool temperature of reason, passion was repressed, grief softened, and peace and resignation became established paramount in a breast in which religion had not lost her sway, though the dwelling of the loftiest patriotic feelings!

After the last gospel, the aged priest, putting off the chasuble, turned around to the congregation, and, in a voice of mingled authority and sweetness, exhorted the large multitude in and around the chapel (the windows of which were raised during the service) to patience and resignation under the sad afflictions which Heaven permitted this unhappy land to be visited with, for some good end. He gently chided them for these manifestations of sorrow for any temporal affliction so unseemly in the house of God. “Your tears will do no good, my good people. Be calm. Weep not for a martyr, for it will only detract from his glory. But, pray that the will of God may be done. He, and He only, can send a Deliverer.” He begged of the people not to expose themselves to punishment and imprisonment, by discussing the subject of the approaching execution in meetings or assemblages, whether in houses or out of doors. Represented it as nothing but madness to attempt any thing like a resistance of the law, however unjust, or to think of rescuing his Reverend friend while he was guarded [19] by several thousand British troops. At this part of the exhortation, there was an evident feeling of disapprobation manifested among the greater portion of the people, especially those at the windows of the chapel, who were principally from the neighboring parishes, and who now began to exclaim, “That will never do.” “If Father O’Donnell is to be hanged like a dog, we must be all shot, or have the life of his murderers.” “Now or never,” cried one. “No more peace preaching,” exclaimed another. “Death to Orange tyrants,” cried a third.

These murmurs becoming louder and more violent, the parish priest, seeing no present chance of allaying the excited feelings of the people, beckoned to the choir to play an afterpiece, and putting on his chasuble, and taking the chalice off the altar, he returned to the vestry.

The large assemblage slowly dispersed, and, moving off in parties of from five to fifty, discussed various plans and organizations for the rescue of Father O’Donnell; but, fur want of a leader their plans were inefficient and impracticable, mere unmeaning speeches!

After having finished his thanksgiving, and after the evacuation of the church and churchyard by the people, the Rev. Dr. O’Healy sent one of the young lads, who assisted at the altar as acolyte, to recmest the stranger, whom we may as well now as afterwards call by his [20] name, Mr. Charles O’Donnell, to speak a word with him in the vestry. It was then, after a few words of explanation, that the priest could account for the weakness manifested during the service, by one who was no pther than brother to the parish priest of Cloughmore, under sentence of death. “How happy I am to see you, my dear child,” said the kind-hearted old gentleman. “Alas, that your visit to your spiritual father (for it was I baptized you) should be occasioned by such a melancholy and heart-rending event as the murder, for it is nothing less, of my best living friend, your dear brother.”

“Well, it must be borne up against with fortitude, if it cannot be averted,” answered O’Donnell.

“Averted! there is not the slightest hope of that. The Government wanted a victim, to strike a salutary terror, as they call it, into the minds of the people, and they fixed on my friend, as the most respectable, as well as the most influential priest, in all Ireland. You heard of the paltry charge on which he was convicted.”

“Yes; for marrying a Protestant gentleman to a Catholic heiress, was it not? “

“That was the sole accusation; but I really think your being in the service of the French monarch caused them to be more inexorable in his regard. Bless you, there were many petitions forwarded to the Lord Lieutenant, and several noblemen interested themselves on [21] his behalf, but all to no purpose. The whole affair, between you and me, was plotted at head-quarters.”

“I shall be able to see him at any rate, I hope.”

“On my word, I doubt it. And, to speak my mind openly, my dear friend, I am greatly afraid if they find out who you are, you won’t soon return back to France , to your regiment. How in the world did you come here at all? If those mustachios on your lip are noticed by any of the British garrison in this town, I am afraid you are a gone man.”

“As to fear, Reverend Father, I have none. And as to telling how I came into your loyal borough of Dungarvan, my oath of allegiance to my superiors forbids me to disclose the secret of my conveyance hither, till after the accomplishment’ of the object I have in view, with God’s assistance.”

They now reached the humble presbytery of the venerable pastor and of both his younger assistants, where a substantial lunch was ready, to which they sat down, after a long fast, both by the priest and his visitor. During the conversation of the evening, nothing struck the aged pastor so much as the imperturbable gravity, and apparently unfeeling coolness of his new acquaintance. He spoke not a word for hours, nor did he join in the discourses of the pastor and his vicars, save in answer to their questions. In fact, his mind appeared absent, or rather, was so intent on the chief [22] thought that engrossed it, that the ordinary remarks of his educated companions, as having no reference to the subject that engaged his attention, seemed to find no access to his intellect. This unusual reserve was at once perceived by the Rev. gentlemen whose guest he was, and they had too much experience and knowledge of human nature not to suspect that this sudden and mysterious visit, after an absence of many years, of Charles O’Donnell, portended something more serious than a visit of condolence to his beloved brother on the eve of his death. The two senior clergymen now retired for the night, leaving the parlor to the Captain and Rev. John Murphy, between whom, because they were formerly school-fellows, a very confidential and protracted conversation was carried on, from the two temporary cot and sofa beds in which they preferred to rest for the night. That most exact time-keeper of nature, the cock, had now proclaimed the hour of midnight, and the conference of the former school-mates was terminated by the stealthy visitation of lazy sleep.

|

[...]

|

| Available at Internet Archive - online; accessed 23.04.2024. |

References

Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction (Dublin: Maunsel 1919), lists Rev. Hugh Quigley, ‘A Missionary Priest,’ worked among Chippewa Indians and miners in California (1818-1883) with titles: The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey, or, A Glance at the Future of Ireland (1863); Profit and Loss, or, Life of A Genteel Irish American (1873), inculcates Catholic piety.

John Sutherland, The Longman Companion to Victorian Fiction (Harlow: Longmans 1988); Rev.H[ugh], ‘A Missionary Priest’, 1818-83; b. Co. Clare, ed. Rome and ord. there; worked in American higher education system, resigned to live among Chippewa Indians and California miners; d. Troy, New York; novels include The Cross and the Shamrock, ‘An Irish-American Tale’ (1853); The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey (1863), 18th c. romance; Profit and Loss, or the Life of A Genteel Irish American (1873).

Clare People (Clare Library) styles him a ‘legendary figure in American history’; son of namesake; b. Dec. 1819, in Tulla, Co. Clare; ed. by headgeschool teacher called Master Walsh and nick-named Sean Cam [DIB Shawm Kaum]; also under Madden in Killaloe; worked with Ordnance Survey, Dublin; notes difference in further accounts of his education:

‘One is that he went to Rome where he studied for the priesthood and graduated with first class honours and received the Gold medal from Sapienza University. Another version is that he studied at St. Mary’s Seminary in Youghal, County Cork and on graduation was ordained in Glasgow.’

Clare People further mentions his early involvement in plans for the 1848 Young Ireland Rising and his disappointment at poor organisation; he held the opinion that ‘stealing was not a sin when it was necessary to feed starving children’; clash with authorities; left Ireland and received a doctorate in theology in Rome in late 1847; invited to the New York diocese by Bishop Hughes; initiated construction of Catholic churches; won lawsuit concerning use of Bible in public schools; engaged in construction Catholic churches; worked with Chippewa Indians near Lake Superior and afterwards with the miners of California. Bibl., The Cross and the Shamrock (1853 in Boston), The Prophet of the Ruined Abbey, written a year later in 1854 (published 1863 in Dublin), Profit and Loss (1873 in New York) and The Irish Race in California and on the Pacific Coast (publ. 1878 in San Francisco); d. Troy, NY, 30th April 1883; bur. St. Mary’s Cemetery, Troy. Thanks expressed to Johana [sic] R. Schwartz, Calif. [Available online; accessed 22.09.2023.]

Note - Hugh Quigley (1819-83) is somewhere called the ‘Rector of the Univ. of St. Mary’ in Chicago. [poss. in Stephen Brown, Ireland in Fiction, 1919]. There does exist a University of St. Mary of the Lake - being the home of Mundelein Seminary, the major seminary and school of theology for the Archdiocese of Chicago and the largest Catholic seminary in the USA - but there are no allusions to it in other biographical notices.

[ top ]

Notes

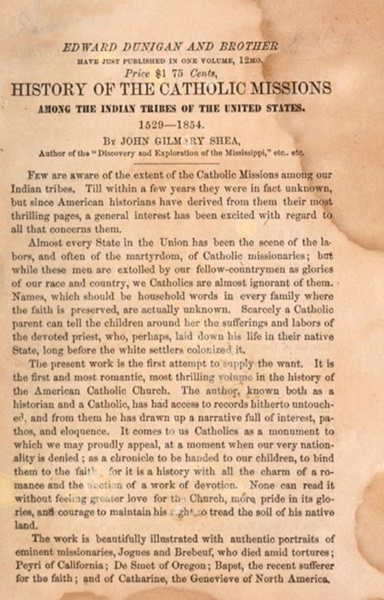

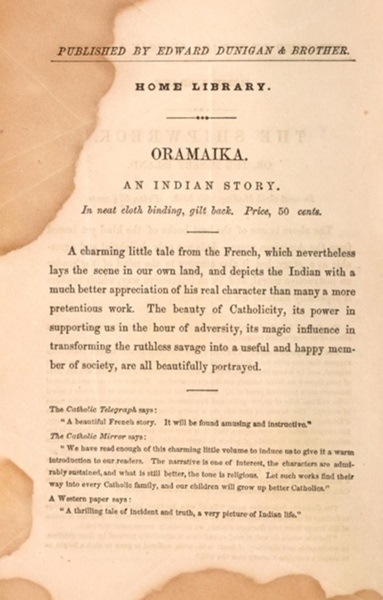

Dunigan & Bro: Front matter to The Prophet incls. advertising for Edward Dunigan and Brother (publishers):

Namesake (1): Hugh Quigley [1895- ]. author of Housing and Slum Clearance (Methuen 1924); ed., Lanarkshire in Prose and Verse: An Anthology [The County anthologies, 2] (London: E. Mathews & Marrot 1929), xviii, 148pp., map; The Highlands of Scotland (Batsford 1949), and other works incl. Passchendaele and the Somme: A Diary of 1917 (Naval and Military Press 2017).

Namesake (2): Hugh Quigley, born 1849 Perth, Lanark, Ontario, Canada died 1935 East Grand Forks, Polk, Minnesota; son of Anne Frances (Quigley) Butler and Thomas Hugh Quigley; m. Philomene Ducharme [Wikitree - online].

[ top ]

|