Life

| 1790-1856; b. 10 Oct., Thomastown Castle, Cashel [i.e., Thomastown], Co. Kilkenny; his f. was agent to Lord Llandaff; ed. St Kieran’s College; entered Maynooth, 1807, and left shortly after, having been disciplined for hosting a party in his room; studied in Dublin 1808-14, and ordained in diocesan orders; joined the Capuchins [friars], and was briefly worked in the mission in Kilkenny, then moving to Cork; he opened a free school for the poor in Cork and formed a society of young men to relieve poverty; fnd. a temperance crusade, commencing on 10 April 1838 at Blackmoor Lane, Cork, with the slogan, ‘Here Goes in the Name of God’; |

| settled after much reflection and prayer on the formula of the Total Abstinence Pledge; advanced through Limerick, Nenagh, Galway, and Dublin, winning hundreds of thousands to the movement; he next extended the crusade to centres of Irish population in Britain, 1844; a journey to America in 1849-51, commencing in New York, where he was greeted by Vice-President Fillmore, he took in 25 states and 300 cities; made an address to the House of Representatives [var. granted a seat within the bar of the Senate and on the floor of the House]; received by delegation and dined with President Taylor; |

| during the Famine he upbraided the ‘capitalists of the corn trade’ who exported corn through Cork but was critical of Young Ireland, and often considered deferential to the upper classes; he wrote to Pitt that his conciliatory policies in Ireland ‘will prove you the most fortunate Minister that ever presided over the destinies of this mighty Empire’; he received a civil list pension from Lord John Russell in 1847, and was criticised by Catholic hierarchy incl. - notably by Archb. John MacHale of Tuam; his proposed nomination for the Cork bishopric was supported by F. S. Mahony [“Father Prout”] but opposed by Bishop Delany and the Irish clergy, fearing his intolerance of drink; |

|

his later years were clouded by ill-health and financial difficulties; for some time he stayed in Madeira; d. 8 Dec. 1856, Cobh, following a stroke; bur at St. Joseph’s Cemetery, Cork [?with his brother Charles]; the bronze statue by J. H. Foley on St. Patrick’s Street [Bridge], Cork, unveiled 10 Oct. 1864, is styled “A Tribute from a Grateful People”; another in stone by Mary Redmond is located on O’Connell St., Dublin; there is a commemorative journal, The Father Mathew Record. CAB ODNB DIB DIH [RAF] OCIL |

|

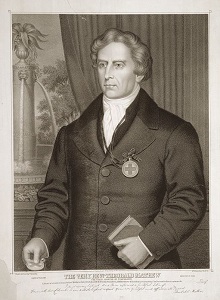

| Fr Theobald Mathew |

top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary| A. M. & S. C. Hall, Ireland, Its Scenery, Character [1841], as Hall’s Ireland: Mr & Mrs Hall’s Tour of 1840 [abridged 2-vol. edn.], ed. Michael Scott (London: Sphere Books 1984) |

| ‘On the 20th August, 1829, the Rev George Carr, a clergyman of the Established Church established the first Temperance Society [17] of Ireland in the town of New Ross. He had read some American newspapers which contained encouraging accounts of the progress the principle was making in the New World, and saw at once that there was no country where it was so much needed as Ireland. For several years however, little way was made, and the advocates of temperance were exposed to contempt and laughter. A coffee tent, which they erected at fairs, was an object of ridicule, and although they had not abandoned hope their efforts were comparatively fruitless, and even the most optimistic amongst them indulged in no idea of large success. Shortly afterwards a temperance society was formed in Cork, the example of New Ross having, by the way, been followed in many other towns. Among its leading members were the Rev. Nicholas Dunscombe, Mr. William Martin, a Quaker, and two tradesmen, Mr. Olden, a slater and Mr. Connell, a tailor. They conceived the idea of consigning the important task into the hands of the Rev. Mr. Mathew, then highly popular in the city and respected by all classes. He met these gentlemen, seriously pondered their plans and probabilities of succeeding, and ultimately - though not immediately - joined them, ‘hand and heart’. On the 10th April, 1838, the Cork Total Abstinence Society was formed. It is certain that Mr. Mathew never for a moment anticipated the wonderful results that were to follow its establishment, and was probably as much astonished as any person in the kingdom when he found not only thousands, but millions, entering into a compact with him to ‘abstain from the use of all intoxicating drinks’ - and keeping it! His Cork society was joined by members from the very distant parts - from the mountains of Kerry, from the wild sea-cliffs of Clare, from the banks of the Shannon, and from places still further off. He had travelled through nearly every district of Ireland, held meetings in nearly every town, and on the 10th October, 1840, his list of members contained upwards of two millions five hundred and thirty thousand names. [... &c.’, with extensive remarks on Irish drunkenness. [...] |

| For longer extract, see RICORSO Library, infra. |

W. P. Ryan, The Irish Literary Revival (London 1894; rep. Lemma Publishing Corp. NY 1970), writes: ‘Realising this inborn love of the Celt for knowledge and lore of so many kinds, it is no wonder that there should be to-day a band of Irishmen whose first purpose is to convince their brethern that devotion to those scholastic and literary ideals is the surest sign of their being true to themselves; that Ireland has need of men who would be apostles of study and culture, as essentially Father Mathew was an apostle of temperance.’ (pp.5-6.)

Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar: A Study of ... William Carleton (1947; Talbot Press 1972): ‘On the twenty-seventh day of July, 1846, had seen the “doomed plant bloom in all the luxuriance of an abundant harvest.” Returning from Dublin to Cork on the third day of August he saw with sorrow one wide waste of putrefying vegetation. “A blast more destructive than the simoon of the desert has passed over the land, and the hopes of the poor potato-cultivators are totally blighted, and the food of a whole nation has perished.”’ (pp.131-32.) Also quotes his response to the cataclysm: ‘Divine Providence in its inscrutable ways has again poured out upon us the vial of its wrath.’ (Ibid., p.131.)

Cf. - ‘These poor creatures, the country poor, are now homeless and without lodgings; no one will take them in; they sleep out at night. The citizens are determined to get rid of them. They take up stray beggars and vagrants and confine them at night in the market place, and the next morning send them out in a cart five miles from the town and there they are left and a great part of them perish for they have no home to go to.’ (1847; quoted on the “Travel Through the Ireland Story” website of Wesley Johnston [online; accessed 31.10.2011].

‘[...] Father Matthew wrote to Trevelyan: “In many places the wretched people were seated on the fences of their decaying gardens, wringing their hands and wailing bitterly the destruction that had left them foodless.”’ (Quoted in The History Place - Irish Potato Famine - online; accessed 31.10.2011.)

Colm Kerrigan, Father Mathew and the Irish Temperance Movement 1838-1849 (Cork UP 1992), McHale though him a faker and called him a ‘vagabond friar’, and no bishop in Ulster wanted him around their place; Mathew refused to identify his movement as Catholic; he took the path of charismatic preaching instead of founding an organisation; one of his biographers , Sister Mary Francis Clare, the ‘Nun of Kenmare’ had no doubt that miracles at his grave were a token of his sanctity; shortly before his death, Fr Mathew said, ‘we hve turned the tide of public opinion; it was once a glory for men to boast of what they drank; we have turned that false glory into shame’ [Kerrigan, p. 184]; most significant in rural areas, not towns. The present work takes up questions raised by H. F. Kearney, Fr. Mathew, Apostle of Modernisation (1979), and Elizabeth Malcolm, Ireland Sober, Ireland Free, Drink and Temperance in 19th c. Ireland (Dublin 1986), and according to this reviewer (James Flynn, Holy Cross Coll., Mass.), he does not advance the question much. Father mathew did not want to co-operate with O’Connell, ‘Political discussion and religious controversy should be avoided in teetotal societies’. Kerrigan quotes a Mr. Hackett who greeted him at a Cork meeting with the flattering verses, ‘And when monarchs and deeds of past ages / are from memory’s tablets effaced / Illumined on history’s pages / Shall the bright name of Mathew be traced.’ Also refers to German traveller Kohl who witnessed the event and wrote: ‘I fancied that Father Mathew ... should have disclaimed the gross flatteries which the orator uttered in his presence.’

[ top ]

References

Charles Read, ed., A Cabinet of Irish Literature (3 vols., 1876-78), gives bio-details, b. Thomastown, Co. Kilkenny; ed. by Lady Elizabeth, Earl’s dg., Kilkenny Coll., and Maynooth; ord. 1814; nursed sick during cholera epidemic in Cork, 1832, and saved a man about to be buried; joined a Unitarian and a Quaker who had already founded a Temperance Society, signing the oath 10 April 1838 with the words, ‘Here goes in the name of God.’. 156,000 soon enrolled, with 150,000 in Limerick, Dec. 1839; Dublin; visited Ulster against advice in 1841; Glasgow, 1842; tour of England, where 600,000 pledged, 1843; in charge of Cork south depot during Famine, 1845; New York, 1849, entertained by President; returned Ireland 1851, and after several attacks of apoplexy died Queenstown. T. F. Meagher’s address at his grave in Cork Cemetery, ‘In the centre of the beautiful graveyard he had himself thrown open to the poor of every church [i.e. denomination] undert the great stone cross, this glorious good man – all that is mortal of him – sleeps. Beside that cross – clinging to it in the agony of a breaking heart – kneels the nation whose cup of poison he changed into one of living waters – whose head he lifted up and crowned with lilies when she had become a reproach among the nations. As silent as the cities of Tyre and Edom shall Ireland have become, when, in the shadow of that cross, without the city of St. Finbar, the Irish heart forgets the noblest, gentlest spirit that ever soothed it.’ The statue in Cork is by Foley.

Dictionary of National Biography, gives details: ord. 1841 [err.]; preaching in London described by Mrs. Carlyle, 1843; worked energetically during Irish famine; visited America, 1849; returned, 1851.

[ top ]

Quotations

Drinking in Maynooth: ‘The prejudice that pervades Maynooth in favour of strong drink is a mystery to me, and I do not know how to account for the delusion except by attributing it to the machinations of Satan.’ (review of Colm Kerrigan, Father Mathew, 1992; Q. source.)

The Great Hunger (1947-49): ‘Divine Providence in its inscrutable ways has poured upon Ireland the vials of wrath.’ (Fr Mathew; quoted in Desmond Ryan, The Phoenix Flame, p.21; see Patrick Rafroidi, Irish Literature in English, The Romantic Period, 1789-1850, Vol 1, 1980; also quoted in Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar, 1947, 1972, p.131.)

[ top ]

Notes

J. C. O’Callaghan: The Green Book, or Gleanings from the Writing-desk of A Literary Agitator (1841) refers to ‘the exertions of the Rev. Mr. Matthew [sic], whose success, in such a noble cause, may be regarded by Irishmen as the strongest test, as the surest precursor, that still “greater things shall they do”. (p.xiii).

William Carleton dedicated Art Maguire to Mathew as ‘the providential instrument of producing among his countrymen the most wonderful and salutary chanve that has ever been recorded in the moral history of man.’ (See Benedict Kiely, Poor Scholar, 1947; 1972, p.116.)

W. M. Thackeray: ‘There is nothing remarkable in Mr. Mathew’s manner, except that it is exceedingly simple, hearty, and manly, and that he does not wear the downcast, demure look which, I know not why, certainly characterises the chief part of the gentlemen of his profession. ... He is almost the only man, too, that I have met in Ireland, who, in speaking of public matters, did not talk as a partisan.’ (Irish Sketchbook, 1842; Blackstaff, 1985, p.68.)

Govt. revenue from spirits duty fell from £1.4 to 0.8 million in a few years, as half the population became pledged teetotallers; introduced to House of Representatives, USA; offered bishopric by Vatican; final years spent in Cobh. There is a painting of the ‘Apostle of Temperance receiving a Repentant Pledge-Breaker’ by Joseph Haverty, a Galway artist (1794-1864) in the National Portrait Collection. And note also, poem on Fr Matthew [sic] by RR Madden, in Memoirs (ed. 1891), ‘her priests and her people again be her crown’.

Portrait: The monument in Cork is by Foley, while there are two figures of Theobald Mathew by John Hogan (1840) and an oil portrait by Alex. Chisholm; see also Joseph Haverty, “Theobald Mathew Receives Repentant Pledge-Breaker” (1844).

The Great Maria: J. F. Maguire, Father Mathew [1862] is cited in Michael Hurst, Maria Edgeworth and the Public Scene (Macmillan 1969), p.112, ftn.

Cork wit: ‘The smell on Patrick’s Bridge is wicked; / How does Father Mathew stick it?’ (anon.)

[ top ]