Life

| 1879-1949 [Robert Wilson Lynd; occas. pseud. “Roibeárd Ua Floinn” or Ó Floinn]; descended from Charles Lynd, Presbyterian minister - and son and grandson of others - who settled at Rathmullen (though shipbound for Larne); b. 20 April, Brookhill Ave., Cliftonville Rd., Belfast, 2nd of seven children of Robert John Lynd, Presbyterian minister [at May St. Presbyterian Church] and Sarah (née Rentoul); ed. Royal Acad. Inst. (RBAI) and QUB, 1896-97; fnd. he Belfast Socialist Society and meets James Connolly; his mother dies running for a train, 1896; grad. in classics, 1899; appt. reporter in Northern Whig, 1899; afterwards worked as a reporter on Manchester Daily Dispatch, 1900, before moving to London; attended perfomance of Synge’s Riders to the Sea; |

| shares studio with Paul Henry - a friend from QUB - while doing freelance journalism in London, and later in Guildford, Surrey; contrib. articles to Today and Black and White; learns and teaches Irish for the Gaelic League, St. Andrew’s Hall (Oxford St.), teaching Roger Casement, 1902-03; attends Cloghaneely Summer College with Casement; there meets Dublin-born poet Sylvia Dryhurst, 1904; m. Dryhurst 21 April, 1909, with whom 2 dgs. (Sigle and Máire) [var. met at London Gaelic League]; contrib. to Hobson’s The Republic, 1906; issued The Orangemen and the Nation (1907); suffered death of his father, 17 Nov. 1907; asst. lit. ed. to Daily News (becoming News Chronicle in 1930), 1908, serving as lit. ed. 1912-47; settles at 14 Downshire Hill, Hampstead; issues Irish and English (1908); |

| becomes reader for Mills & Boon; dg. Sigle b. 28 Feb., 1910; dg. Máire b. 2 March, 1912; issued Rambles in Ireland (1912); lit ed., Daily News, 1913, columnist in the Nation from 1908 and later for New Stateman (ed. J. C. Squires), 1913-45; genial and witty essays signed “Y.Y.”; supporter of Gaelic League and - more covertly - Sinn Féin, writing under the pseud. ‘Riobard Ua Floinn’ in Uladh, 1905, and elsewhere; The Mantle of the Emperor (1906); parts with Casement over the latter’s IRB membership; rejected by army, 1914; encouraged Padraic Ó Conaire (see letter of 13 May 1915); |

| writes “If the Germans conquered England”(1915), printed in the Irish War News; organises the defence of Casement with Alice Stopford Green, 1916; retires to Sussex during Zeppelin raids; commences heavy drinking; wrote introduction to reprint of to James Connolly’s works (Labour in Ireland, Labour in Irish History, and The Reconquest of Ireland (1917); published collected vols. of his essays and other books such as Home Life in Ireland (1909), Ireland a Nation (1919), The Art of Letters (1920), and Dr. Johnson and his Company (1929); Lynd wrote the literary section in Saorstát Eireann: Irish Free State Official Handbook (1932), which was edited by Bulmer Hobson; |

| his essays for New Statesman and Nation were published progressively in thirty volumes; moved to 5, Keats Grove, London, where the Joyce’s were guests at the time of their wedding, 1931; visited by Denis Johnston, 1934; moves to Dorking, 1943; writes as ‘John o’ London’ in magazine of that name; struck by motorcycle, sustaining broken ribs; ‘YY’ column ends; part-time lit. ed. of New Chronicle; QUB D.Litt, 1946; retires 20 April; d. 6 Oct. 1949; bur. Belfast City Cemetery, when his funeral was attended by Seán McBride and Conor Cruise O’Brien - but no representatives of the Northern Ireland State; memorial service, May St., 10 Oct.; Sylvia d., 1952; there is a portrait by William Conor. ODNB DIW DIB DIL OCEL KUN APP DUB OCIL |

| [ top ] |

|

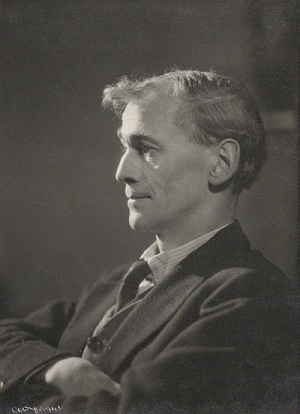

| Robert Lynd by Howard Coster (NPG, Lon.). |

[ top ]

Works

|

| Pamphlets |

|

|

| Selections |

|

Bibliographical details

Rambles in Ireland

by Lynd, Robert

Published: 1912, Mills & Boon (London)

Statement: by Robert Lynd. With five illustrations in colour by Jack B. Yeats and twenty-five from photographs.

Pagination: 312pp.

Subject: Ireland — Description and travel.

Ireland — Social life and customs

Available at Internet ArchiveC

L

A

R

E

L

I

B[ Copy held in Univ. of California Libraries]

Ireland a Nation (London: Grant Richards MDCCCCXIX 1919), epigram Gen. Smuts; includes successive chapters on under the caption ‘Voices of the New Ireland’, devoted to Dora Sigerson Shorter, Patrick Pearse, Tom Kettle, J. R. Green, and “AE” [George Russell]. The whole takes the view that Irish culture and the Irish mind were repressed by British colonialism, and that only in the late nineteenth century does it begin to emerge again; quotes extensively from Thomas MacDonagh, in Literature in Ireland (1916).

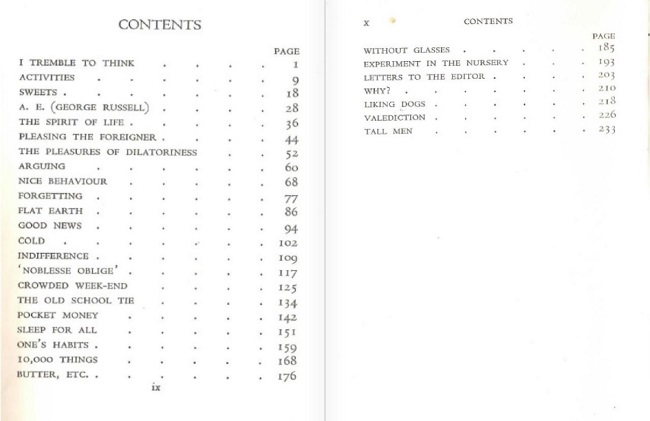

I Tremble to Think (1936) [ Available at Internet Archive - online ].

See .. “I Tremble to Think” - full text > as attached.

“A.E.” [George Russell]- full text > as attached.

[ top ]

Criticism| Articles & Notices |

|

| Bibliography |

|

See also Irish Book Lover, Vols., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 13 , for frequent references.

[ top ]

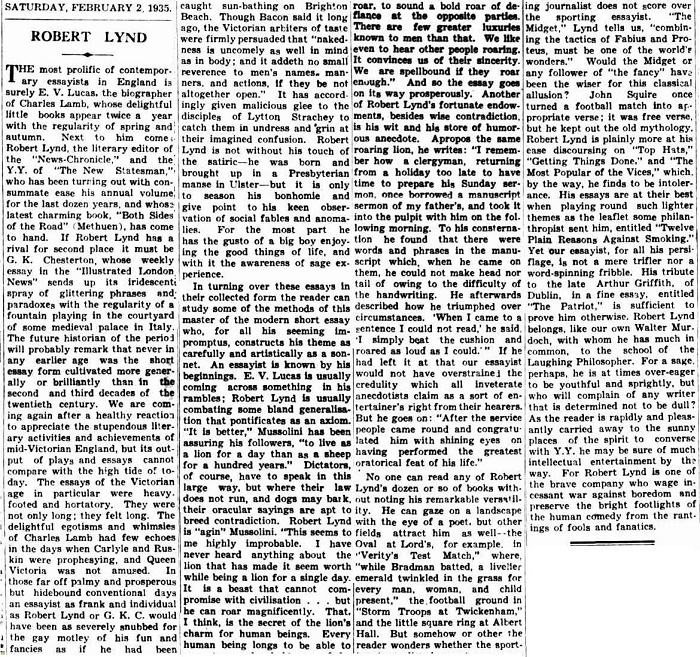

Commentary

Robert Greacen, Brief Encounters, Literary Dublin and Belfast in the 1940s (1991), ‘[... ]Robert Lynd, the gentle essayist and convert to Home Rule, whose father had been a minister at May St. Presbyterian Church. Lynd had found success in London. Rumour had it that he was a hard drinker who once said to a fellow boozer in a Fleet St. tavern, ‘do you realise that we are the kind of men our mothers warned us against?’ [10].

Robert Greacen, reviewing Patricia Craig, ed., Rattle of the North, in Books Ireland (Oct. 1992), à propos Northern Harvest (1944): ‘I managed to get an introduction out of Robert Lynd, then a notable man-of-letters and essayist in London. / Lynd wrote, “No such collection as this of Northern Irish literature could have been made when I was a boy in Belfast ... the omens for the future are good ...”.’

Dan Finlay, ‘The Man Who Bridged the Northern Gap’, in Books Ireland (April 2001), calls for a re-appreciation of Beflast Writer Robert Lynd’; quotes from the essay of the name, ‘As a rule, a man who trembles to think is a man who has scarcely paused to think.’ (pp.97-98.)

[ top ]

| Essays from I Tremble to Think (1936) |

| “I Tremble to Think” [title-essay] - as attached. |

| “A.E.” [George Russell] - full text > as attached. |

Saorstát Eireann: Irish Free State Official Handbook, ed. Bulmer Hobson (1932), contains “The Ethics of Sinn Fein” by Roibeárd Ua Floinn [Robert Lynd], with sects.: “Our Moral Obligations”, “The Necessity for Individual Actions” [‘Every Irishman who does not speak Irish is against his will a representative of English domination in Ireland’, 361], “The Policy of Mé Fein” [‘each should put into practice ... the Irish nation in miniature’, 361], “Inter-dependence of State and Individual”; “Good Example” [‘best method of propagating SF policy’], “Our Models” [Emmet, Davis], “The difference Between the Average nationalist and the Average Unionist” [meetings equally noisy], “All Depends Upon Determination” [‘no honest Irishman is the enemy of Ireland’], ‘“Brute Force versus Moral Persuasion”, “Self Sacrifice” [quotes St. Paul, ‘if he had not charity ...’], “The Selfish Policy”, “The Remedy is in Our Own Hands” [‘when every nationalist makes his or her character strong and self-reliant and beautiful, English domination will die for sheer lack of sustenance ... The only way to become a patriotic Irishman is to do your best to become a perfect man’, 368 END]. Note: ‘The Ethics of Sinn Fein’ [supra] is cited as a separate title [pamph.] (Dublin ?1919), in D. George Boyce, Nationalism in Ireland (Routledge 1982), p.333.

[ top ]

“A Pre-Boswell Group” [chap.], in Essays on Life and Literature (London: Dent 1951), p.107ff: “[Beauclerk] contended that every wise man who intended to shoot himself should take two pistols in order to make sure of achieving his object. Beauclerk’s droll humour unfortunately led him to produce a false argument in support of his contention. “Mr. [-]”, he declared, “who loved buttered muffins, but durst not eat them because they disagreed with his stomach, resolved to shoot himself; and then he ate three buttered muffins for breakfast, before shooting himself, knowing that he should not be troubled with indigestion: he had charged two pistols; one was found lying charged upon the table by him, after he had shot himself with the other. ” Johnson triumphantly pointed out that this showed the sufficiency of one pistol. But Beauclerk, maintaining that this was only because one pistol for the nonce had been effective, added sharply: “This is what you don’t know, and I do. ” Johnson seems to have brooded for a few minutes over this piece of rudeness, for after some time he burst out: “Mr. Beauclerk, how come you to talk so petulantly to me as “This is what you don”t know, but I know”?” “Because,” said Beauclerk, like an offended child, “ you began by being uncivil (which you always are).” Johnson again allowed the conversation to go on for some time before returning to the fray, but, during a discussion that arose on the violence of the Rev. Mr. Hackman’s temper, he observed pointedly: “It was his business to command his temper, as my friend, Mr. Beauclerk, should have done some time ago.” “I should learn of you, sir, ” retorted Beauclerk. “Sir,” said Dr. Johnson, “you”ll have given me opportunity enough of learning, when I have been in your company. No man loves to be treated with contempt.”

“A Pre-Boswell Group” (1951): ‘It is a scene of childish tantrums such as we find recurring again and again in the story of the relations between Johnson and his friends. Apart from the story of the buttered muffins there is neither wit nor wisdom exhibited on either side. Boswell, however, saw that if he was to make Johnson real, he must allow him to behave as naturally in his biography as he had behaved in life, and that petty scenes are as likely to reveal the variety of a man’s nature as great ones. It is because Boswell did not shrink from exhibiting his characters in their silliness as well as in their greatness that Johnson is the most real figure in English biography. We catch Johnson as we catch Pepys, when he is off his guard, and seem to know him better almost than we know ourselves. / And his readiness to make up a quarrel is made as clear in the scene as his readiness to take and give offence. An apology from Beauclerk brought immediate peace and was followed by a late [sitting]; and Boswell records that Johnson and he “dined at Beauclerk’s on the Saturday se’nnight following.” / There were few of Johnson’s friendships that were not diversified in this fashion with an occasional squabble. Even Bishop Percy and Sir Joshua Reynolds became actors in what Parliamentary reporters call “scenes.” Johnson and his friends played the game of conversation as vigorously as if it had been Rugby football. Johnson, besides, was an outspoken and penetrating critic of those he loved best, both to their faces and behind their backs. He would accept friendship on no other terms. His affection never blinded him to his friends” faults, nor, on the other hand, did his moral judgment blind him to their virtues and social graces. He might disapprove on moral grounds of Beauclerk’s marriage to the divorced wife of another man, and say to Boswell, who defended it: “My dear sir, never accustom your mind to mingle virtue and vice. The woman’s a whore, and there’s an end on ‘t.” But none the less he could dine with Beauclerk and Lady Di as cheerfully as he could dine with Whigs, whom he considered scarcely less immoral. He was content to live his own life and to let other people live theirs, provided they had the great virtue of sociability. He was not a man who could resist the spell of Beauclerk’s humour, so easy in its flow and so apparently undesigned. “No man,” he declared enthusiastically of Beauclerk, I ever was so free, when he was going to say a good thing, from a look that expressed that it was coming; or, when he said it, from a look that expressed that it had come.” Johnson felt that he himself laboured when he said a good thing and that, in at least one grace of conversation, Beauclerk excelled him. [For further at this point, see under Arthur Murphy, infra.]

“A Pre-Boswell Group” (1951): ‘Some people, as they read the life of Johnson, may find themselves wondering at times whether he had ever any real friends at all-whether, when all is said, his eminent characteristic was, not a genius for friendship, but a genius for acquaintanceship. Certainly, it is difficult to believe that he ever loved any of his friends as Lamb loved Coleridge. Many of his friends are rather like boon companions, with conversation taking the place of wine as the bond of union. At the same time, if a boon companionship becomes permanent, it is unreasonable to deny it the name of friendship. Johnson himself was, in his appreciative moods, so exuberant in praise of his acquaintances that we probably think of them as having been more intimate friends than they really were. What, for example, could be more exuberant than his tribute to Dr. Burney: “My heart goes out to meet him. I much question if there is in the world such another man as Dr. Burney?” Yet in spite of this tribute, amiable a figure though Dr. Burney is, and vivaciously though his family lives in Fanny Burney’s diary, it is difficult to imagine any great intimacy between him and Johnson. When we first meet him, it is as an unknown admirer in the days of the Rambler, who wrote to express his admiration of the author and to inquire how he could order six copies of the forthcoming Dictionary for himself and his friends. Johnson, though indolent, was polite, and the letter in which he replied to Burney led to the addition of yet another satellite to the shining planet that we know as Dr. Johnson. Two years later, when the Dictionary had appeared, and Burney had duly commended it, we find Johnson writing gratefully: “Your praise was very welcome, not only because I believe it was sincere, but because praise has been very scarce. Yours is the only letter of goodwill I have received.” On this foundation of mutual gratitude, Burney was a welcome guest when, a year afterwards, he called at Gough Square.’ (p.109.) [I am indebted to Joan Boyd for sight of this text: BS.]

‘Who Began It?: The Truth about the Murders in Ireland’ by Robert Lynd [being pamph.] issued by the Peace in Ireland Council [1919]: ‘Mr Lloyd George always suggests in his speeches on Ireland that the series of murders now being committed by the Armed Forces of the Crown are in the nature of reprisals. [...] “Reprisals” is only a euphemism for murder; and responsibility for the murders on both sides rests primarily with the immoral violence of a Government which met the demand of a small nation for self-government, not with the fourteen points, but with violence.’ (See longer extract.)

[ top ]

R. F. Foster: ‘Robert Lynd, at school in Belfast, received the advice: “Escape, fly while there is time!”’ (Paddy and Mr Punch: Connections in Irish and English History (London: Allen Lane [Penguin] 1993) [q.p.; see extracts - as attached.]

|

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

|

[ top ]

Margaret Drabble, ed., Oxford Companion to English Literature (OUP 1985), characterises Lynd as a ‘light essayist devoted to Ireland’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 3, makes reference to early commentary on the critical writings of Thomas MacDonagh, Robert Lynd, Ireland A Nation (Grant Richards 1919), pp.164-70 [563n].

Brian Walker et al., eds, Faces of Ireland (Appletree 1992), selects On factory conditions in Ulster, an extract from Home Life in Ireland (Lon 1904), pp.229-30.

Libraries

University of Ulster Central Library, Home Life in Ireland (1909); Ireland a Nation (1919), reflecting strong nationalist sympathies; The Blue Lion (1923); Dr. Johnson and Company (1927), and 31 others (not listed). BML CAT incl. Rambles in Ireland, ill. Jack B. Yeats (1912); Dr. Johnson and Company (1927; Penguin ed. 1946); numerous introductions to selections and anthologies of English poetry, incl. life and letters of Keats; an introduction to James Connolly’s Labour in Irish History (1917 ed.); Ireland a Nation (Grant Richards 1919) [246pp.]; If the Germans Conquered England (Dublin & London: Maunsel 1917), p.xiii, 158; and Why Irish should be taught, a reply to Why Should We Teach Irish in the Municipal Technical Institute, by A. B. Wilson (1907), 8vo.Belfast Central Public Library holds 15 titles including Dr. Johnston and His Company; Home Life in Ireland; Modern Poetry (1939); I Tremble to Think.

Belfast Linenhall Library holds Home Life in Ireland (1908); Irish and English Painters and Impressionists (1908); also Rambles in Ireland (illustrated Jack B. Yeats, n.d.) [cf. Rambles in Eirinn, by William Bulfin].

Library of Herbert Bell (Belfast) holds Rambles in Ireland (London 1912); The Green Man (London 1930); The Pleasure of Innocence (London 1921); The Peal of Bells (London 1925); Solomon in All His Glory (London 1922); Life’s Little Oddities (London 1941); The Cockle Shell (London 1936); The Money Box (London 1925); Things one Hears (London 1947); I Tremble to Think (London 1936); YY (London 1933); Irish & English (London 1908); Dr Johnson and Company (London N.D.) [2 copies]; The Blue Lion (London 1925); Home Life in Ireland (London 1909)

[ top ]

Notes

Pseud.? Lynd is possibly the ‘L’ of prefatory note to Thomas Kettle, The Ways of War (1917), and possibly ghost-author of Memoir by Mary Kettle. The Memoir repeats the view expressed by John Dillon about the executions of 1916. Cf., ‘Mr Lynd, whom I have quoted so frequently because he understood my husband as it is given to few to understand another, calls the last lines of his “Reason in Rhyme” his testament to England as his call to Europeanism is his testament to Ireland [See “Bond from the toil ... &c., in Kettle, q.v.]

Un-listed.: Roibeard Ua Floinn is not among the otherwise exhaustive list of Gaelic pseudonyms listed by Richard Hayes in Clár Litreachta.

P. S. O’Hegarty’s Irish Nation is ded. to Lynd and Hobson.

Daniel Corkery instances criticism of Synge by three Northern writers, Robert Lynd, Forrest Reid, and St John Ervine, as ‘the artillery of the Black North’ (Sygne and Anglo-Irish Literature, 1931, p.vii) and later as ‘the Belfast sentimentalists’ (ibid. p.94). See Patrick Walsh (MA Thesis on Corkery, UUC 1993) [cp.85.]

Namesake: Cf. Robert S[taughton]. Lynd, Knowledge for What?: The Place of Social Science in American Culture (1945), by the author of Middletown and Middletown in Transition. Lynd’s papers are held in the American Library of Congress; see also John S. Gilkeson, Anthropologists and the Rediscovery of America, 1886-1965 (Cambridge UP 2010).

Query: Papers of Robert Lynd are held at James Joyce Foundation [Centre], Dublin?

[ top ]