Life

| 1891-1917 [‘the Irish Keats’]; b. 19 Aug., Janevill[e], Slane, Co. Meath; eighth of nine children; when his father died young [1896], his mother Anne [née Lynch, 1853-26] went to work in fields; prevented from eviction only by a doctor who refused to permit the removel of his tubercular elder brother Patrick, who later died, and was buried at the expense of the Navan Co. Council; left school at 14; worked as a labourer and later in a copper mine at Beaupare; elected sec. of Slane branch of Meath Labour Union, 1912 [1913-14]; led labour action in short-lived mining industry in Slane, and was sacked as trouble-maker [1910]; fell in love with Ellie Vaughey, who married another and died in childbirth in 1915; headed Slane branch of Irish Volunteers, 1914, and travelled to Manchester to rally support; his first poems appeared in Drogheda Independent; on advice of local sculptor encountered in Conyngham Arms, he contacted Lord Dunsany, who responded to his personality and talent with an invitation to use the castle library and a small gratuity to enable him to write; issued Songs of the Fields (1915); voted against Redmond’s Woodenbridge declaration at three successive meetings of the Volunteers in Meath; met hostility in Slane and travelled to Dublin, where he enlisted in Dunsany’s regt., 5th Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers Inniskilling Fusiliers [10th (Irish) Division], at Richmond Barracks (Inchicore), believing that “the British Army stood between Ireland and an enemy common to our civilisation”; | |

|

|

| promoted to lance-corporal; stationed at Basingstoke; saw action at Sulva Bay (Gallipoli) where there were 50% casualties, and in Serbia, participating in the 90-mile forced-march retreat from Salonika; collapsed en route [in Serbia], losing all his manuscripts, and hospitalised in Cairo for four months; afterwards transported home to Manchester; denied request to leave army on medical grounds; composed his elegy for Thomas MacDonagh during home leave in Manchester, May 1916; visited Dublin and saw ruins in O’Connell Street; (‘if someone were to tell me now that the Germans were coming in over our back wall, I wouldn’t lift a finger to stop them. They could come!’); brought before court-martial and demoted for unauthorised absence; | |

|

|

| stationed for seven months at Ebrington Barracks (Londonderry/Derry) and served as batman to Dunsany in his residence, Government House on the Letterkenny Rd.; reinstated as corporal before posting to Belgium where he joined the regt. at Picquigny, north of Amiens, in Dec. 1916; drafted to B Company, 1st Battalion Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers [29th Division]; posted to Carnoy, then to Le Neuville nr. Corbie; conducted a correspondence with Katherine Tynan; billeted in Le Neuville, early March, 1917; reached 1st Arras, April 1917; moved to Proven nr. Ypres, 27 June; served in trenches; ‘blown to bits’ by a shell at Boezinge [Boesinghe, nr. Pilkem] while laying duck-boards in preparation for an attack on Ypres (Third Battle; also known as Paschendaele), 31 July; his death recorded by a chaplain, Fr Devas, who also wrote that he had heard Mass and made a confession shortly before; bur. at the crossroads where he died, and later reburied at Artillery Wood cemetery (Boezinge) nearby, at Plot II. Row B. Grave 5, with gravestone inscription: ‘16138 / F. E. Ledwidge Lance Corp. / Royal Inniskilling Fus. / 31st July 1917 Age 29’. | |

|

|

| Complete Poems were edited by Dunsany and published by Herbert Jenkins, 1919; a life by Alice Curtayne was published in 1972; the Selected Poems was edited by Dermot Bolger (1993), with a foreword by Seamus Heaney, counting Ledwidge among the ‘walking wounded’; a memorial to Ledwidge was unveiled in 1998 in the Island of Ireland Peace Park at Messines at the spot where he was killed - inscribed with words of his elegy for Thomas MacDonagh: ‘He shall not hear / The bittern cry / In the wild sky / Where he is lain’; another was unveiled at the National War Memorial [Lutychens] Gardens at Islandbridge, Dublin, in 2005 - a Ledwidge Commemorative Festival having been established there in 27 July 1997, being addressed by Dermot Bolger and others; there is an Ulster History Circle Blue Plaque to Ledwidge in the former Ebrington Barracks, Londonderry; his contributions to the Drogheda Independent were compiled as Legends and Stories of the Boyne Side (1914) but never circulated; a single recovered copy was published with some short stories and an autobiographical letter to Lewis N. Chase [Library of Congress, Washington DC, Chase Papers, Ac.9468, Box 7] by Riposte Books/Inchicore Ledwidge Society in the 1970s and later as Legends of the Boyne and Selected Prose, ed. Liam O’ Meara (Dec. 2006); Walking the Road (2007), a play on Ledwidge by Dermot Bolger was staged at the Civic Theatre, Tallaght (Dublin) and Ieper [Ypres] in 2007. ODNB DIB DIW DIH DIL OCEL KUN FDA G20 HAM OCIL DIB (Cam.) |

|

| [ top ] |

|

|

|

|

|

|||

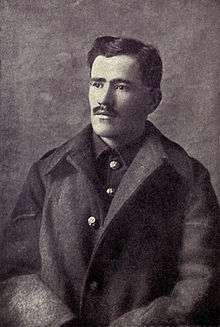

| Memorials of Francis Ledwidge (incl. Janeville Cottage, plaque on Slane Bridge, and ports.) | |||

Works

Works, Songs of Peace (London: Herbert Jenkins 1917), intro. Lord Dunsany [Plunkett]; Songs of the Fields [ed. Lord Dunsany] (London: Herbert Jenkins 1918); The Complete Poems of Francis Ledwidge, with an Introduction by Lord Dunsany (London: Jenkins 1919; rep. 1955).

| Coll. & Selected Editions |

|

Songs of Peace, by Francis Ledwidge, with an introduction by Lord Dunsany (Herbert Jenkins Ltd [1917]), Intro., 5-8pp., Poems 15-110pp., incl. sections, ‘At Home’; ‘In Barracks’; ‘In Camp’; ‘At Sea’; ‘In Serbia’; ‘In Greece’; ‘In Hospital in Egypt’; ‘In Barracks’ [“Thomas McDonagh” and some 10 others].

Miscellaneous, John McQuaid, Songs of Francis Ledwidge (Scottish Music Centre [q.d.]), 16pp.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ There is a life by Donal Lowery in Dictionary of Irish Literature [new edn.] (Cambridge UP 2010) - see copy as attached. ]

[ top ]

Commentary| Some Elegies ... |

|

Grace Conkling, “Francis Ledwidge”: ‘Nevermore singing / Will you go now, / Wearing wild moonlight / On your brow. / The moon’s white mood / In your silver mind / Is all forgotten. / Words of wind / From off the hedgerow / After rain, / You do not hear them; / They are vain. / There is a linnet / Craves a song, / And you returning / Before long. / Now who will tell her, / Who can say / On what great errand / You are away? / You whose kindred / Were hills of Meath, / Who sang the lane-rose / From her sheath, / What voice will cry them / The grief at dawn / Or say to the blackbird / You are gone?’ (In Jessie B. Rittenhouse, The Second Book of Modern Verse, Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. 1922; rep. in Bartleby [online].) Norreys Jephson O’Conor, “In Memoriam: Francis Ledwidge”: ‘Soldier and singer of Erin, / What may I fashion for thee? / What garland of words or of flowers? / Singer of sunlight and showers, / The wind on the lea; // Of clouds, and the houses of Erin, / Wee cabins, white on the plain, / And bright with the colours of even, / Beauty of earth and of heaven falls / Outspread beyond Slane! // Slane, where the Easter of Patrick / Flamed on the night of the Gael, / Guard both the honor and story / Of him who has died for the glory / That crowns Innisfail. // Soldier of right and of freedom, / I offer thee song and hot tears. / With Brian, and Red Hugh O’Donnell, / The chiefs of Tyrone and Tryconnell, / Live on through the years!’ (W. S. Braithwaite, ed., Anthology of Massachusetts Poets, 1922; in Bartleby online]. Dermot Bolger, “On the 80th Annivesary of the Death of Francis Ledwidge” (Sunday Independent, 27 July 1997): ‘Dream child of the owl’s light, / Of the heron’s flight and the blackbird’s song, / Hearing voices in woodland places / Where your spirit now paces all night long. [...] I cannot think of you rotten / In a line of forgotten graves tonight [...] When, turning the pages, I see you / Running through dew-drenched fields of corn [… &c.]’ |

| Seamus Heaney, ‘In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge’ - Killed in France 31 July 1917 |

|

| —from Field Work (1979); see full poem - as attached. |

Lord Dunsany, My Ireland (Jarrold 1937), Chap. V [on Ledwidge]: ‘I made a collection of his poems and took them to the firm of publishers who sponsors them to this day.’ Further: ‘He [Jarrold] advertised Francis Ledwidge very widely as a scavenger poet [...] I owe it to his memory to say he never was a scavenger.’ (p.57); also speaks of Ledwidge’s being caught up in the patriotic fervour of enlistment.

Lord Dunsany, Preface to Mary Lavin, Tales from Bective Bridge (London: Michael Joseph 1945), pp.5-8: ‘When Ledwidge first brought his work to me I gave him a very little advice, when he immediately profited by, as people do not usually profit by advice. The best thing I did for him was to lend him a copy of Keats; and the great speed with which he seemed to absorb it, and slightly to flavour his work with it, gave me some insight into his enormous powers, which were unhappily never developed. But my first impression Mary Lavin sent me some of her work, an impression that I have never altered, was that I had no advice whatever to give her about literature; so I have only helped her with her punctuation, which was bad, and with her hyphens about which she shares the complete ignorance that in the fourth decade of the twentieth century appears to afflict nearly everybody who writes. Only in these trivial matters do I feel that I know anything more about writing than Mary Lavin.’

John Hewitt, review of Alice Curtayne, Complete Poems of Ledwidge (1974), in Hibernia (24, April 1975), makes reference to ‘that fine biography’ by Alice Curtayne of two years previous’.

Keith Jeffrey, ‘Irish Culture and the Great War’, in Bullán (Autumn 1994): Sean Dowling’s play A Bird in the Net provoked a lively reaction by suggesting a homosexual relationship between characters who were taken to represent Francis Ledwidge and Lord Dunsany. (Jeffrey, p.93.)

[ top ]

Seamus Heaney, “In Memoriam Francis Ledwidge”, a poem (Irish Times, May 1980) - as attached; note that Terence Brown cites this poet in a review of Paul Bew, Ideoogy and the Irish Question (OUP 1995), in Irish Literary Supplement (Spring 1996, p.9): ‘You were not keyed or pitched like these true-blue ones / Though all of you consort now underground’. See also Seamus Heaney, essay on Francis Ledwidge, The Irish Times (21, Nov. 1992), where Heaney remarks on Alice Curtayne’s excellent biography, which shows him neither as a poet of woodlands wild nor the ‘dupe of a socially superior and politically insidious West British toff.’ Heaney notes the change after Redmond’s Wooden Bridge speech of 20 Sept. 1914 and sees those who went with Redmond as break-aways as opposed to those who ‘stuck to a more separatist reading of the Volunteers’ pledge to “secure and maintain the rights and loyalties common to the whole people of Ireland”.’ Further, ‘Redmond called them “to drill and make themselves efficient for the work ... not only in Ireland itself, but wherever the firing line extends in defence of rights of freedom and religion in this war.”’ Notes that Ledwidge would not be associated with a motion congratulating Redmond at Navan Rural Council, 10 Oct. 1914; he joined the army in the same month, some say on the rebound from a marriage rejection, others that he was persuaded by Dunsany; quotes Ledwidge, ‘I joined the British Army because she stood between Ireland and an enemy of [recte common to our] civilisation and I would not have her say that she defended us while we did nothing [at home] but pass resolutions.’ Heaney remarks that this is ‘surely one of the rare occasions when the British army is given the female gender’. Ledwidge fought at Gallipoli, the Balkans, and Ypres, where he was killed by a bursting shell, 31 July 1917. Wrote his elegy to Thomas MacDonagh; drank more than usual; reported late for duty; did not desert; of the elegy, Heaney comments, ‘it is a poem in which his displaced hankering for the place beyond confusion and his own peculiar melancholy voice find a subject which exercises them entirely, no doubt because he was to a large extent lamenting himself.’

Note further: Heaney refers to the neglect of regard for the heroism of the men who went to the war, and the increasingly disinclination to pay due regard to the courage of the men who fought in 1916; speaks of ‘the combination of vulnerability and adequacy ... in facing life’ in Ledwidge, and concludes that this poet had a talent neither very original nor very strong, ‘His status as a combatant is finally not as important as his membership of the walking wounded, wherever they are to be found at any given moment.’ (The Irish Times, 21 Nov. 1992.) See also Seamus Heaney, [article on Ledwidge], Fortnightly Review (Dec. 1995).

[ top ]

P. J. Kavanagh (‘Bywords’, Irish Literary Supplement, 27 Sept., 1996; p.16), notes: ‘His widowed mother did casual work in the fieled to feed her family of eight, at a time when the contemporary Bidhof of Kerry described such workers as “the worst-houses, the worst-paid and the worst-fed class of their kind in any civilised country in the word.” For some reason, we always want to discover a “peasant” poet, as though we wish to believe that a landscape of the mind can spring directly from the landscape of birth, without the intervention of art. Perhaps Ledwidge and Clare are the only ones. ... he was helped by Dunsany - “Peer Finds Poet” says the newspaper clipping on the walls of his cottage.’

Robert Greacen, reviewing Liam O’Meara, ed., Complete Poems of Francis Ledwidge, 1997, om in Books Ireland ( Feb. 1998), notes that Ledwidge wrote his poem on Thomas MacDonagh - as infra - while at Ebrington Barracks in Manchester, May 1916; sent first draft to Lilly Fogarty; then proceeded to the better known version, writing on Army issue paper, sending a copy next to Donagh MacDonagh, son of the executed poet. (p.20.)

Gerald Dawe, ‘Francis Ledwidge: A Man of His Time’, in The Irish Times (31 July 2004), p.11: ‘To understand Ledweide is to understand the complex reality of this country. His life tells the fascinating stroy of the tensions of a traditional Irish rural past, characterised by all the cultural resources of a deep-seated respect for learning and argument. This cultural richness was set against the real economic hardship which which went with such a life, and the lack of opportunities outside of agricultural work. / There is a dignity and forbearance about Ledwidge that impressed both those with whom he had dealings as a writer - including Lord Dunsany, Katherine Tynan and others - as well as the neighbours and fellow workers of his youth and young manhood, who were beguiled by his storytelling and his very special, dramatising self-awareness. / Like the young Charles Donnelly, who died in Spain in 1937, Ledwidge’s political and trade union commitments place him. as one of the voices of an emerging Ireland. He was part of that modernising, progressive force in the early decades of the last century, even while most of his poems looked back to an Irish idyll of romantic longing, replicating Gaelic rhythms and mythology as his friend, Thomas MacDonagh, had recommended. / Ledwidge embodies, in Searmis Heaney’s phrase, the “conflicting elements in the Irish inheritance”. This is what makes him such an important figure in our current debates about cultural identity. The Great War represented the shock of the new, as much as the horror of the human carnage. Had Ledwidge survived it, his own poetry may well have adjusted to the radically changed inner world of his personal life. First World War veteran Thoma Mac Greevy comes to mind. [...]’

|

[...] Ledwidge here seems to take a back seat, like an accompanist: his poem’s singer and chief mourner is the allegorical spéirbhean (sky-woman), in her incarnation as the sean bhean bhocht (the poor old woman). Internal rhyme suggests that Ledwidge is consciously echoing Gaelic versification techniques. The imagery, like the allegory, is deeply traditional. The blackbird sings throughout Irish poetry, north and south, from medieval times to the present. Its symbolism is infinitely malleable: the trope is used by Protestant and Catholic poets alike, and mostly without narrowly political intent. Here, though, the blackbirds represent the Nationalist activists, in particular Ledwidge’s friend, Thomas MacDonagh. They have been destroyed by the fowler, England, and their loss is lamented by Ireland in her lowliest guise. Is Ledwidge also regretting the fact that they were led by their sense of injustice from poetry and scholarship towards violence? That interpretation seems perfectly feasible. [...] |

| Available online; accessed 17.08.2015. |

[ top ]

Quotations

“June”: ‘ Broom out the floor now, lay the fender by, / And plant this bee-sucked bough of woodbine there, / And let the window down. The butterfly / Floats in upon the sunbeam, and the fair / Tanned face of June, the nomad gipsy, laughs / Above her widespread wares, the while she tells / The farmers’ fortunes in the fields, and quaffs / The water from the spider-peopled wells. // The hedges are all drowned in green grass seas, / And bobbing poppies flare like Elmo’s light, / While siren-like the pollen-stainéd bees / Drone in the clover depths. And up the height / The cuckoo’s voice is hoarse and broke with joy. / And on the lowland crops the crows make raid, / Nor fear the clappers of the farmer’s boy, / Who sleeps, like drunken Noah, in the shade. // And loop this red rose in that hazel ring / That snares your little ear, for June is short / And we must joy in it and dance and sing, / And from her bounty draw her rosy worth. / Ay! soon the swallows will be flying south, / The wind wheel north to gather in the snow, / Even the roses spilt on youth’s red mouth / Will soon blow down the road all roses go.’

“My Mother”: ‘God made my mother on an April day, / From sorrow and the mist along the sea, / Lost birds’ and wanderers’ songs and ocean spray, / And the moon loved her wandering jealously. // Beside the ocean’s din she combed her hair, / Singing the nocturne of the passing ships, / Before her earthly lover found her there / And kissed away the music from her lips. // She came unto the hills and saw the change / That brings the swallow and the geese in turns. / But there was not a grief she deeméd strange, / For there is that in her which always mourns. // Kind heart she has for all on hill or wave / Whose hopes grew wings like ants to fly away. / I bless the God Who such a mother gave / This poor bird-hearted singer of a day.’

“Spring and Autumn”: ‘Green ripples singing down the corn, / With blossoms dumb the path I tread, / And in the music of the morn / One with wild roses on her head. // Now the green ripples turn to gold / And all the paths are loud with rain, / I with desire am growing old / And full of winter pain.’

“A Little Boy in the Morning”: ‘ He will not come, and still I wait. / He whistles at another gate / Where angels listen. Ah I know / He will not come, yet if I go / How shall I know he did not pass / barefooted in the flowery grass? // The moon leans on one silver horn / Above the silhouettes of morn, / And from their nest-sills finches whistle / Or stooping pluck the downy thistle. / How is the morn so gay and fair / Without his whistling in its air? / The world is calling, I must go. / How shall I know he did not pass / Barefooted in the shining grass?’

“Soliloquy”: ‘When I was young I had a care / Lest I should cheat me of my share / Of that which makes it sweet to strive / For life, and dying still survive, / A name in sunshine written higher / Than lark or poet dare aspire. // But I grew weary doing well. / Besides, ‘twas sweeter in that hell, / Down with the loud banditti people / Who robbed the orchards, climbed the steeple / For jackdaws’ eyes and made the cock / Crow ere ‘twas daylight on the clock. / I was so very bad the neighbours / Spoke of me at their daily labours. // And now I’m drinking wine in France, / The helpless child of circumstance./ To-morrow will be loud with war, / How will I be accounted for? // It is too late now to retrieve / A fallen dream, too late to grieve / A name unmade, but not too late / To thank the gods for what is great; / A keen-edged sword, a soldier’s heart, / Is greater than a poet’s art. / And greater than a poet’s fame / A little grave that has no name.’ [Note: the lines are reproduced on the Ledwidge Memorial at Messines together with a Dutch translation and lines from “Lament for Thomas McDonagh”.]

“To One Dead” [Ellie Vaughey]: ‘A Blackbird singing / On a moss-upholstered stone, / Bluebells swinging, Shadows wildly blown, / A song in the wood, / A ship on the sea. / The song was for you / And the ship was for me. // A blackbird singing / I hear in my troubled mind, / Bluebells swinging / I see in a distant wind. / But sorrow and silence / Are the wood’s threnody, / The silence for you / And the sorrow for me.’ (Inscribed on a stone at Cottage of Francis Ledwidge, Slane.)

“Call to Ireland”: ‘We have fought so much for the nation / In the tents we helped to divide; / Shall the cause of our common fathers / On our earthstones lie denied? / For the price of a field we have wrangled / While the weather rusted the plow, / ’ twas yours and ‘twas mine and ‘tis ours yet / And it’s time to be fencing it now.’

“In France”: ‘The silence of maternal hills / Is round me in my evening dreams; / And round me music-making rills / And mingling waves of pastoral streams. // Whatever way I turn I find / The path is old unto me still. / The hills of home are in my mind, / And there I wander as I will.’

Note: this stanza is reprinted in Thomas O’Grady, ‘A long way to Tipperary ... or to Slane”, The Boston Irish Reporter, 25, 2 (Feb. 2014), where he writes: “In France” typifies how Ledwidge’s poems emphasize the bucolic and the romantic, keeping at literary arm’s length the horrific realities of battlefields and trench warfare’ (p.13). See Irishmatters blogspot - online. [O’Grady had maintained his Irish studies blogspot for 25 years at the date of publication.]

“Lament for Thomas McDonagh”: ‘He shall not hear the bittern cry / In the wild sky where he is lain / Nor voices of the sweeter birds / Above the wailing of the rain. // Nor shall he know when loud March blows / Thro’ slanting snows her fanfare shrill / Blowing to flame the golden cup / Of many an upset daffodil. // And when the dark cow leaves the moor / And pastures poor with greedy weeds / Perhaps he’ll hear her low at morn /Lifting her horn in pleasant meads.’ (See remarks by Robert Greacen, as supra.)

| “Lament for the Poets of 1916” | ||

I heard the Poor Old Woman say: “No more from lovely distances “With bended flowers the angels mark |

“And when the first surprise of flight “But in the lovely hush of eve, |

|

| (Printable copy - as attached.) | ||

[ top ]

“O’Connell Street” (on Dublin 1916) [unpublished poem]: ‘A Noble failure is not vain / But hath a victory of its own / A bright delectance from the slain / Is down the generations thrown. / / And, more than Beauty understands / Has made her lovelier here, it seems; / I see white ships that crowd her strands, / For mine are all the dead men’s dreams.’

See letter from Manus O’Riordan in The Irish Times (28 Nov. 2002) —

Madam, - Two years after the murderous Battle of the Somme it was still a front being fought over. It was there that a first cousin of my maternal grandfather, John Sheehy of Clonakilty, was killed on February 15th, 1918. There was indeed much heartbreak and sorrow among his family, not least because he had died as British cannon-fodder.

I am reminded of such family history on reading Suzanne Lynch’s account of the Anthem for Doomed Youth exhibition (November 25th). She rightly pays tribute to the beauty and poignancy of Francis Ledwidge’s verse, but she misconstrues his oft-quoted statement about “an enemy common to our civilisation” as a famous defence of his decision to join the British Army.

In an autobiographical letter to Lewis Chase just eight weeks before his death on July 31st, 1917, Ledwidge used these words to describe the sentiments that had originally motivated him to enlist back in October 1914. But such an anti-German outlook no longer motivated him. Home on leave in May 1916 in the wake of the executions of Easter Rising leaders, including Pearse and McDonagh, whom he described as “two of my best friends, shot by England”, Ledwidge told his brother Joe that “if I heard the Germans were coming in over our back wall, I wouldn’t go out now to stop them. They could come!”

In his unpublished poem O’Connell Street Ledwidge protested that the Easter Rising should not be dismissed as a “noble failure” made in vain, but that it “hath a victory its own” to be “down the generations thrown”. This conviction continued to inspire him to the very end. In the aforementioned letter to Lewis Chase he expressed his hope that “a new Ireland will arise from her ashes in Dublin, like the Phoenix, with one purpose, one aim, and one ambition. I tell you this in order that you may know what it is to me to be called a British soldier while my own country has no place among the nations but the place of Cinderella”.

That indeed was the true depth of the tragedy of Ledwidge’s own death. - Yours, etc.,

Manus O’Riordan,

Finglas Road,

Glasnevin,

Dublin 11.[Available online; accessed 17.08.2015.]

‘He will not come, and still I wait. / He whistles at another gate / Where angels listen. Ah, I know / He will not come, yet if I go / How shall I know he did not pass / Barefooted in the flowery grass. // The moon leans on one silver horn / Above the silhouettes of morn, / And from their nest-sills finches whistle / Or stooping pluck the downy thistle / How is the morn so gay and fair / Without his whistling in its air? // The world is calling, I must go. / How shall I know he did not pass / Barefooted in the shining grass?’ (Quoted in Jennifer Johnston, This is Not a Novel, Review [Hodder Headline]: 2002, p.100; see infra.)

| War-time letter to Katherine Tynan-Hinkson |

|

| Tynan, The Years of the Shadow (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company 1919), p.289; quoted in Norreys Jephson O’Conor, Changing Ireland: Literary Backgrounds of the Irish Free State, 1889-1922 (Harvard UP 1924) [Chap. IX: Some Irish Poets of the Allied Cause in the World War"], p.145. |

[ top ]

References

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day Co. 1991), Vol. 2, selects “June” from Songs of the Fields; “A Twilight in Middle March”, “Lament for Thomas MacDonagh, from from Songs of Peace; “The Shadow People, “The Herons”; and “At Lisnaskea”, “Derry”, “The Sad Queen”, and “A Dream” from Songs of Peace. bibl. [774] notes that Curtayne’s edn. contains poems not included by Dunsany. See A. N. Jeffares, Anglo-Literature (1980), p. 185.

Chadwyck-Healey English Poetry Full-Text Database CD-ROM [Release One], holds two poems entitled “In Memoriam: Francis Ledwidge”, the earlier one by Norreys Jephson Connor and the later by Seamus Heaney.

Belfast Central Public Library holds Songs of Peace (1917); Songs of the Fields (1918); Complete Poems (1944, 1955).

Websites: see “The Cottage of Francis Ledwidge”, Slane [online]. Toronto Poetry Database (gen. ed. Ian Lancashire) holds four poems of Ledwidge: “Behind the Closed Eye”, “June”; “Soliloquy; “Spring and Autumn” [link]. See also entry at “First World War” website [link].

[ top ]

Notes

Slane Bridge: the first stanza of his elegy for Thomas MacDonagh was carved on memorial plaque to be set in parapet of Slane Bridge, but is now affixed to Ledwidge’s Cottage (‘He shall not hear the bittern cry / In the cold grave where he is lain ...’)

Dermot Bolger, ed., Francis Ledwidge: Selected Poems (Dublin: New Island Books 1993): purports to clarify his reputation smudged by the over-inclusiveness of Curtayne’s earlier edn., viz., Complete Poems (1974).

Jennifer Johnston: The grandmother of the heroine and narrator in Johnston’s This is Not a Novel (2002), sets Ledwidge songs to piano-music and has attached a copy of verses from Ledwidge’s poem in memoriam Thomas MacDonagh (‘He shall not hear the bittern cry ... ’) to a notice of her son Harry’s death at Suvla Bay [Gallipoli] in the World War I. Amongst these are: ‘He will not come, and still I wait [...&c.]’ (p.100, as supra - and, oddly, given da capo at pp.212-13.)

See also her references to ‘work on the third Ledwidge song’ (ibid., p.148), and note that the poem whose ‘bumpy rhythm’ begins to come to the same character later is also by Ledwidge: ‘A blackbird singing / On a moss-upholstered stone ... A blackbird singing I hear in my troubled mind ... sorrow and silence / Are the wood’s threnody, / The silence for you / And the sorrow for me’, p.130, and see p.177, where this is confirmed.) The whole novel is dedicated on the final page: ‘In memory of Francis Ledwidge, killed in France 31 July 1917’.

Philip Orr, Field of Bones: The Gallipoli Campaign (Dublin: Lilliput Press 2005), gives account of the Dardenelles arising from the author’s visit to a friend in Westmeath where housing for ex-soldiers was somewhat derisively called “The Dardenelles” first aroused his interest. He relates that the 10th Division, which drew in 32 per 10,000 men in the South of Ireland, was supplemented by several hundred troops from Yorkshire and Wales; landed at Suvla Bay, early Aug. 1916; suffered three thousand casualties; in 1921, 120 officers and 1,200 men were awaiting psychiatric treatment at Leopardstown Hospital, a higher proportion than elsewhere in the British Isles. (Books Ireland, Sept. 2005, p.174 [interview with author].)

[ top ]