Life

1964- [fam. “Ginger”; family name derived from Mag Ruairc, of Viking origin, poss. Norse Hrothrekr]; b. in Edgeworthstown [Mostrim], Co. Westmeath; first collection Shale (1994), issued by Gallery Press, was winner of the Brendan Behan Memorial Prize, 1994; joint-winner of Rooney Prize Special Award with Conor O’Callaghan, 1996 - and whom she married; her early poetry collections incl. Other People’s Houses (1999) and Flight (2002), winner of Sunday Tribune and Hennessy awards; introduced Gallery edition of Goldsmith’s Deserted Village (2003); issued Juniper Street (2006) and a translation of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, Lament for Art O’Leary (2008); Spindrift (2009) became the Poetry Society Recommendation [UK]; read poems on RTÉ in 2003 and has broadcast on BBC;

issued The Lament of Art O’Leary (2008), a translation of Caoineadh Airt Uí Laoghaire of Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill; served as editor of Poetry Ireland Review, Nos. 113-120 (up to Jan. 2017); elected to Aosdána, 2009; served on judging panel for New Zealand’s Sarah Broom Poetry Prize, 2015; recipient of Cullman Fellowship at the NY Public Library, 2018-19, and wrote Hereafter: The Telling Life of Ellen O’Hara (2022), a poetic account in sonnet-form of the experience of Irish domestic servants in 1890s New York; winner of the 2024 Michel Déon Award; publ. Infinity Pool (2025), short-listed for T. S. Eliot Prize; taught at Villanova University and Wake Forest University in the U.S and holds a post at the Centre for New Writing at the University of Manchester; Writer in Residence at St John’s College, Cambridge, 2022-26; recipient of the Irish Literary Hall of Fame Award, 2017; appt.to the Irish Chair of Poetry, Sept. 2025 and gave inaugural lecture, 26th Feb., 2026 at TCD.

[ top ]

Works| Collections |

|

| Selected/Collected |

|

| Prose |

|

| Translation |

|

| Reviews (sel.) |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Bibiographical details

Infinity Pool (Oldcastle [Co. Meath]: Gallery Press 2025), 63pp.. Contents: “Stansted to Knock, December 21st”; “With the moon in full spate such that”; “Infinity Pool”; “An Poll Gorm / The Blue Hole”; “Inner Space”; “Nocturne With Ink”; “Imagine the Atlantic as an Actor”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Mechanic”; “The Tell”; “Mise en Scène”; “Lint”; “Setting My Mother’s Hair as an Ars Poetica”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Journalist”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Chambermaid”; “The Low Road”; “Proposition”; “Still Life in Marble”; “Tipping Point”; “What the day offers, so the day demands”; “May the Tenth”; “Snapshot”; “Two Kinds of Ending”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Film-Maker”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Bartender”; “The Future of the Poem”; “In the Cemetery of Non-existent Cemeteries, Gdańsk”; “Hindsight”; “Short Poem About Self-consciousness”; “Introduction”; “Imagine the Atlantic as an Artist”; “Imagine the Atlantic as a Poet”; “The Copybook”; “Ending Without a Poem -- My Own Fourth Wall -- Reading Chinese Love Poems in a Borrowed English House -- Acknowledgements.

Contributions to poetry collections

Making for Planet Alice: New Women Poets, ed. Maura Dooley (Newcastle upon Tyne: Bloodaxe Books 1997), 173pp. [ports]. Contribs.: Moniza Alvi, Eleanor Brown, Siobhan Campbell, Tessa Rose Chester, Kate Clanchy, Julia Copus, Jane Duran, Gillian Ferguson, Janet Fisher, Linda France, Elizabeth Garrett, Lavinia Greenlaw, Vona Groarke, Sophie Hannah, Maggie Hannan, Tracey Herd, Jane Holland, Jackie Kay, Mimi Khalvati, Gwyneth Lewis, Sarah Maguire, Sinead Morrissey, Alice Oswald, Ruth Padel, Katherine Pierpoint, Deryn Rees-Jones, Anne Rouse, Eva Salzman, Ann Sansom, Susan Wicks.The Coast Road, by Ailbhe Ní Ghearbhuigh (Oldcastle: The Gallery Press 2016), 119pp. [Selected poems in Irish with English translations by Michael Coady, Peter Fallon, Tom French, Alan Gillis, Vona Groarke, John McAuliffe, Medbh McGuckian, Paul Muldoon, Michelle O’Sullivan, Justin Quinn, Billy Ramsell, Peter Sirr, David Wheatley.]

16, foreword by Barry Whelan, intro. by Declan Kiberd [An Post in assoc. with Poetry Ireland; commemorating the 1916 Rising] (Dublin: Stoney Road Press 2016), [68]pp., ill. [2 lvs. of col. pls.; poems and translations by Michael Canning; Harry Clifton, Eva Gore-Booth; Vona Groarke, Francis Ledwidge; Alice Maher; Paula Meehan; Paul Muldoon; Caoimhín Ó Conghaile; Brian O’Doherty; Patrick Pearse; Kathy Prendergast; traidisiúnta: Ró;isín Dubh ; traditional: John O’Dwyer of the Glen; Lady Jane Wilde ; W. B. Yeats - table of contents available at COPAC/Discovery Hub - online].

Contributions to critical collections

Chosen Lights: Poets on Poems by John Montague in Honour of his 80th Birthday (Oldcastle: Gallery Press 2009), 132pp. [with Justin Quinn, Alan Gillis, Gerald Dawe, Dermot Healy, Paul Muldoon, Gerald Smyth, Ciaran Carson, Seamus Heaney, Vona Groarke, David Wheatley, John McAuliffe, Medbh McGuckian, Eavan Boland, Peter Fallon, Seán Lysaght, Michael Longley, Ciaran Berry, Michael Coady, Peter Sirr, Conor O'Callaghan, Sara Berkeley, Bernard O’Donoghue, Rosita Boland, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Aidan Rooney, Dennis O'Driscoll, Tom French, Eamon Grennan, Derek Mahon, and Frank McGuinness.]Seamus Heaney in Context, ed. Geraldine Higgins (Cambridge UP 2021), xiv, 369pp. [with Patrick Crotty, John McAuliffe, Margaret Greaves, Sarah Bennett, Matthew Campbell, Ron Schuchard, Meg Harper, Stephen Regan, Catriona Clutterbuck, John Redmond, Vona Groarke, Bernard O'Donoghue, Brendan Corcoran, Simon B. Kress, Heather Clarke, Nathan Suhr-Sytsma, Marilynn Richtarik, Aidan O'Malley, Kieran Quinlan, Florence Impens, Jonathan Allison, Rosie Lavan, Richard Rankin Russell, Laura O'Connor, Kevin Whelan, Justin Quinn, Deepika Bahri, Nicholas [Allen?], Fintan O'Toole, Rand Brandes, Chris Morash.

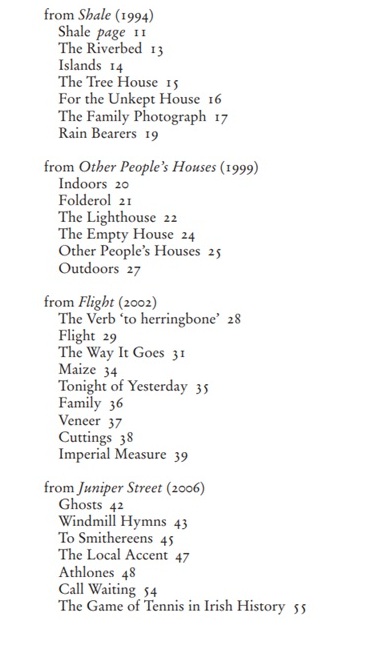

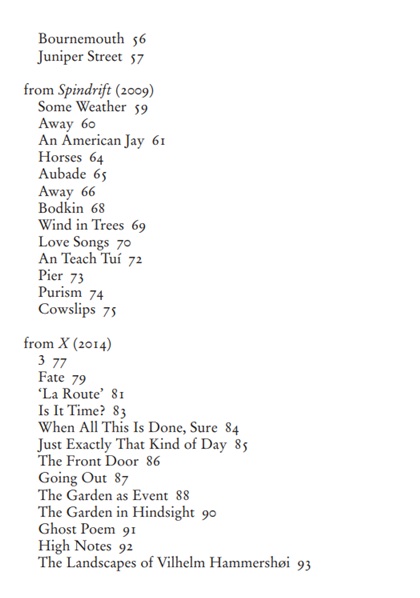

Selected Poems of Vona Groarke (Gallery Press 2016)

Table of Contents—Available at Gallery Press - Vona Groarke, Selected Poems - Preview [.pdf].

[ top ]

Criticism

|

|

[ top ]

Commentary

Rita Kelly, ‘The Sinew of Memory’, review of Other People’s Houses, in Books Ireland (March 2000), writes: ‘Critics have been struck by Groarke’s sensibility, the assurance and regulated qualities of her voice. [...] This is a kind of poetry which echoes back through the poetry we know well, the poetry which has left an impression upon the brain, as it were. It recalls Emily Dickinson more than Elizabeth Bishop. It has a new England daring directness about it. But perhaps these are qualities which belong to the Border-Midland region of Ireland? It is a poetry of inclusion too; there is a very strong sense of the other, the “you” or the joint experience. At its best it is daring, sensitive and gentle. //It is quite daring too to take the House theme and stretch it over a collection, something as familiar, comfortable, ordinary and universal. The notion of sheltering ourselves from an inclement planet with whatever household gods are dear to us; even if we don’t have a house we still aspire to one. And there is the sense too that our house belongs to her people. Groarke deals with the reality of modern, quasi-urban living as we replicate ourselves in the façades of our neighbours’. (p.64.)

David Wheatley, review notice of Flight (Gallery Press), 74pp., in Times Literary Supplement [5 July 2002]; notes epigraph from Oliver Goldsmith: ‘Sunk are thy bowers in shapeless ruin all’; cites poems, “The Verb ‘to Herringbone’”; “Choose one version”; “The Way it Goes” (‘Turn it. Let it go. See how it spins.’); “Shot Sillk”; “Worldl Music”; “Pop”; “Or to Come”; “The Bower”, et al. Remarks of “Imperial Measure” that Groarke lets us deduce the momentous nature of the Easter Rising of 1916 from its effects on the cellars of Dublin’s Four Courts [quoting:] ‘the spirits kept their heady confidence, for all the stockpiled bottles / had chimed with every hit, and the calculating scales above it all / had the measure of nothing, or nothing not of smoke, and then wildfire.’

Sinéad Morrissey, review of Vona Groarke, Other People’s Houses, and Conor O'Callaghan, Seatown (both Gallery Press), PN Press PN Review (Jan.-Feb. 2000) [available online]. When the new owner of Marilyn Monroe’s mansion began renovation, nothing was as it seemed: the loft insulation turned out to be a false cover for a twisted network of wires and bugging devices allegedly laid by the White House, the CIA and the Mafia. The ironic discovery that a private milieu had been the locus for illicit exposure is one which sits well with the theme of Vona Groarke’s second collection Other People’s Houses, as nearly all of the book’s numerous houses, like fairground “fun-houses”, shatter our expectations.

The pivotal poem is “Domestic Arrangements”, which is divided into fourteen sections with two tightly rhyming quatrains apiece. Each part describes a room in an upper-class house. The sections all work in the same way: the intended use or effect of each room is introduced in the first quatrain and then subverted in the second, either by physicality, or by sex, or by the ugliness of the economic exploitation upon which Great Houses were founded. Thus in the conservatory “future daughters of the house” may “languish and endure / the promise of orchids”, but in reality the glasshouse functions as a hideaway for covert sex: “The glass obscured by rubber plants / the heat at any hour / supply ideal conditions / to graft or to deflower.” The tightness of the form Groarke employs makes such inversion disturbingly inevitable: in each case there is nowhere to go but down.

“House-rules” is another Janus-faced poem structured around ...

[Page restricted to subscribers to Poetry Nation Review; aupported by the Arts Council of England.]

[ top ]

Quotations

“The Verb to Herringbone”, poem, contrib. to The Irish Times: ‘Something beginning with slightness and possibly/taken from there. As though unheard of, inauspicious,/the way a pheasant or a wood-pigeon/will find a point of no return, on a lorryless/side-road or on the lee side of an air./Something begun and verring off at once//as though to double back would be the point/of it and diminution be a slight recall:/something with an underscore,/though currently usure how to proceed/or to convince. Like the verb “to herringbone”/or the air displaced by flight.’ (Irish Times, April 2000; Weekend; q. date.)

|

|

[ top ]

“En Route”: ‘Even the Foxford rug is black and white / though matted with a wayward heat / that makes your fingers swarm under the cover / in a lapful of your sleek, unsworn intentions […]’. (In The Irish Times [Weekend], 26 Jan. 2002.)

“Archaeology”: ‘[...] Let’s skew it with a spray of last night’s dreams: / rain that tasted of copper; houses made of silver-foil; / a piglet in a Babygro, for fun. And then, at last, to tie the whole thing up, a woman on an unknown road, / waving a cloth so red it bleeds out on her hand, / the empty road, an inscrutable sky.’ (End; quoted in James J. McAuley, review of Windmill Hymns, in The Irish Times, Weekend (12 Feb. 2005).

| ‘Very musical chairs’, review of The Poet’s Chair: The First Nine Years of the Ireland Chair of Poetry, in in The Irish Times (8 March 2008) [paragraphs here condensed for screen]. | ||

|

||

| See full review at RICORSO > LIbrary > Criticism > Reviews - as attached. |

| [ back] | [ top ] |

Notes

Daniela Theinová, Limits and languages in contemporary Irish women’s poetry (Palgrave Macmillan 2020)- according to publisher’s summar, Theinova incls discussion of Groarke in her survey: ’Limits and Languages in Contemporary Irish Women’s Poetry examines the transactions between the two main languages of Irish literature, English and Irish, and their formative role in contemporary poetry by Irish women. Daniela Theinová explores the works of well-known poets such as Eavan Boland, Eiléan Ní Chuilleanáin, Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill, Biddy Jenkinson and Medbh McGuckian, combining for the first time a critical analysis of the language issue with a focus on the historical marginality of women in the Irish literary tradition. Acutely alert to the textures of individual poems even as she reads these against broader critical-theoretical horizons, Theinová engages directly with texts in both Irish and English. By highlighting these writers’ uneasy poetic and linguistic identity, and by introducing into this wider context some more recent poets—including Vona Groarke, Caitríona O’Reilly, Sinéad Morrissey, Ailbhe Darcy and Aifric Mac Aodha - this book proposes a fundamental critical reconsideration of major late-twentieth-century Irish women poets, and, by extension, the nation’s canon. (For chapter titles - see COPAC/Discovery Hub - online.)