Robert C. Kennedy, “On This Day”, in The New York Times (30 Sept. 2001)

[Note: See “On This Day”, in The New York Times (30 Sept. [2001]) - online; accessed 18.03.2017.]

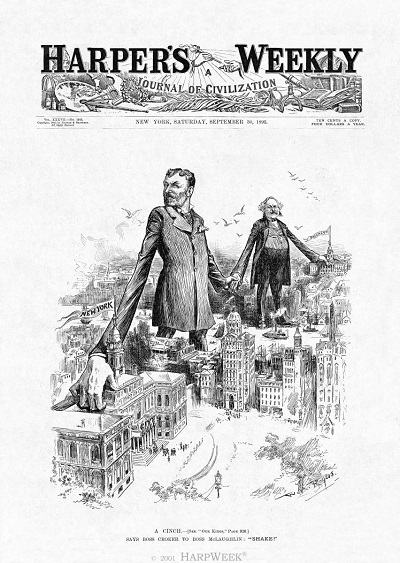

On 30 Sept. 1893, Harper’s Weekly featured a cartoon about

political bosses Richard Croker and Hugh McLaughlin.

“A Cinch - Says Boss Croker to Boss McLaughlin: ‘Shake!’ (Cartoon by William Allen Rogers)

Cartoonist W. A. Rogers portrays the alliance between the two giant bosses of New York City’s Democratic machines, Richard Croker (left), the “Master of Manhattan,” and Hugh McLaughlin (right) of Brooklyn, as a menace to good government in the metropolis. The corresponding commentary, “Our Kings,” by editor Carl Schurz, compares the men to the seventeenth-century Stuart kings who tried to rule England as absolute monarchs. He characterized the political machines as “a fixed system of despotic rule ... in each of these nominally democratic communities...”

Richard Croker was born in County Cork, Ireland, in 1843, and immigrated with his family to the United States three years later. They soon settled in New York City, where young Croker sporadically attended the common schools until becoming a machinist’s apprentice at the age of 13. A scrappy street fighter, Croker led the Fourth Avenue Tunnel Gang, through which he came to the attention of Alderman (and later sheriff) Jimmy O’Brien, who became his political mentor. After associating with the anti-Tweed Young Democracy, Croker broke with O’Brien in 1872, and was taken under the wing of Tammany Hall’s new “reform” boss, John Kelly.

Running on the Tammany Hall slate in 1874, Croker was elected coroner, but he allegedly shot and killed an opponent in an election day brawl. Charged with murder, the subsequent trial ended with a hung jury, and he was not retried. The incident became an integral part of Croker’s reputation, so that twenty years later Carl Schurz (in the aforementioned editorial) identified him as the political boss who “once distinguished himself by killing a man, which some old-fashioned people considered an objectionable feature of his career.”

On June 2, 1886, as the Tammany Hall executive committee was conferring on a new boss to replace Kelly, who had died the day before, Croker strode into Kelly’s office and took over the organization’s reins. For the next sixteen years, Croker would serve as Tammany Hall boss, more administratively effective than Kelly, and more politically ruthless than Tweed. During the late 1880s and early 1890s, Croker consolidated Tammany’s power by eliminating its rival Democratic machines, and ensured the mayoral election of Tammany lieutenants, Hugh Grant (1888, 1890) and Thomas Gilroy (1892). Croker worked toward his clearly stated goal of having all city posts from mayor to office porter filled by Tammany Hall members, who numbered 90,000 during his tenure.

In 1889, Mayor Grant appointed the Tammany boss to the lucrative office of city chamberlain, where he was responsible for all city deposits. He resigned the next year, though, and thereafter drew no salary from the city government or Tammany Hall. Only a few years earlier, Croker had been struggling financially, but now he was able to buy an expensive mansion on Fifth Avenue, invest large amounts in high-priced racehorses and real estate (in the United States, England, and Ireland), and was estimated to be worth several million dollars.

Unlike Tweed, Croker probably did not take his money directly from Tammany Hall graft, which was funneled into the machine’s coffers. Instead, shortly after becoming boss, he established a real estate partnership, which sold land to the municipal government; in addition, he earned handsome profits from city contracts awarded to numerous firms in which he had a financial interest. When an investigating commission asked Croker whether he was working as boss for his own “pocket,” he replied, “All the time, the same as you.”

The six years of almost unrestrained rapacity halted in 1894 when the Lexow Committee uncovered massive corruption in the police department. Tammany Hall’s enemies cooperated temporarily, causing the machine’s slate of candidates to lose in the fall election to a reform coalition. However, after spending the next three years in England, Croker returned to see his handpicked candidate, Robert Van Wyck, win the first mayoral election after the five boroughs had merged into the single municipality of New York City. In 1899-1900, more revelations of corruption in city government led to the ouster of Tammany officeholders in the 1901 election, and the end of Croker’s reign as Tammany boss. He resigned, and spent he remaining years wintering in Florida and living on an estate in Ireland, where he died in 1922.

Hugh McLaughlin was born to a poor, immigrant Irish family in Brooklyn, New York, about 1826 (year uncertain). He received little education in his youth, but labored, instead, as a rope-maker, dock worker, and fishmonger. In 1849, he began working for Brooklyn’s Democratic political boss, Henry C. Murphy, and in 1855 was given the patronage position of master (civilian) foreman at the Brooklyn naval yard. The job allowed McLaughlin to distribute patronage, which he used to build support for his successful quest to become the new boss of Brooklyn’s Democratic Party in 1862.

Like most political bosses, McLaughlin’s authority was not absolute, and he occasionally lost favor; yet, he consistently held power until 1903. Never interested in state or national politics, McLaughlin was able to sustain friendly relations with more powerful Democrats, such as Samuel J. Tilden, Grover Cleveland, Croker, and, especially, David B. Hill. The Brooklyn boss made a fortune in real estate, generously donating large sums to charity, and spent several months a year hunting and fishing in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. In 1903, the new Tammany Hall boss, Charles F. Murphy, orchestrated the forced retirement of McLaughlin, who died the next year.

| [ close ] | [ top ] |