Life

| b. North London, to Irish parents, 27 June 1950 of parents from Laois and Sligo who returned to the family farm in Ireland; grew up in Hollyfort [nr. Gorey], Co. Wexford; he lived in Barcelona before returning to Dublin in the 1970s; attended Gorey Arts Festival, 1971; he underwent an amputation and spent numerous periods of hospitalisation and convalescence with constant pain; elected a member of Aosdána; his poetry collections incl. Those Distant Summers (1980), After Thunder (1985); a one-act play, Cardinal (1991), premiered Hamburg; |

| issued The Fabulists (1994), a novel about Tess and Margo, two young women on the dole queue in 1990s Dublin, published by Anthony Farrell of Lilliput Press; lissued The Water Star (2000) which follows five Londoners in aftermath of the blitz, with final sequence in Ireland, followed by The Fisher Child (Nov. 2001), a story of abuse and vengeance, completing the Bann River Trilogy; winner of the Listowel Novel of the Year Award, 1995; his poetry collections incl. Those Distant Summers (1980) and After Thunder (1985); Dialogue in Fading Light (2005), a second selection, was launched by Ronan Sheehan in the Oak Room of the Mansion House, Dublin (Aug. 2015); his children’s fiction incl. The Coupla (2015), a novel about twins whose mother walked into the sea; guest writer at ABEI Symposium of Irish Studies 2011 (São Paolo, Brazil); |

| lived in Arran St., Dublin 2 (a small terrace house with a red door); closely associated with Marion Kelly as soulmate and friend; d. 2018 following long and stoical illness; survived by siblings Peter and John and Karina; renowned for his gift of selfish friendship by many; he created “The Fabulist”, a webpage incorporating the ‘Dictionary of Contemporary Irish Writers’ - later enlarged as “Irish Writers Online”, being a comprehensive database of contemporary poets, dramatists and novelists; founded with Kelly and Ronan Sheehan The Funks of the Screw, modelling on the 18th c. club associated with J. P. Curran. FDA |

| Philip Casey was a committed website builder who created “Irish Writers Online”, a comprehensive database of contemporary poets, dramatists, and novelists - and created websites for others including one for disabled people. He also maintained an active personal blog on Irish literary topics [both defunct at 27.12.2022]. |

|

|

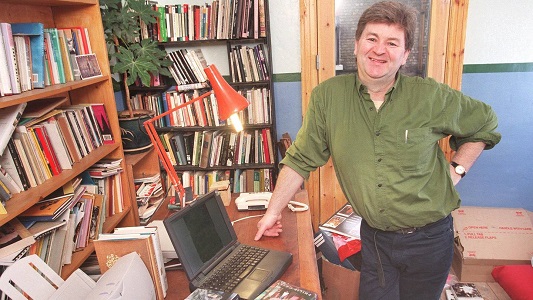

| Photo by Matt Kavanagh (Irish Times) | RTÉ |

[ top ]

Works| Poetry collections |

|

| Fiction, |

|

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

[ top ]

Criticism

Interview, Books Ireland (Oct. 1994) [self-admitted surrealist]; review of The Fabulists in Times Literary Supplement (18, Nov. 1994) [down-and-out-ers in Dublin, ‘spoofing’]. See also feature-article on on the publication of his Selected Poems in The Irish Times (27 Aug. 2015).

Colm Tóibín - Tribute in The Irish Times (5 Feb. 2018):

Later, he lived in Barcelona, making a small set of streets around Placa Lesseps into his own territory, his own village. I thought of him as a born poet, someone who loved how a poem could turn on the single image around which he gathered the poem’s tension. I was amazed, then, when I read his first novel The Fabulists, published in 1994. It is a great, vivid novel about Dublin, with a marvellous opening chapter, which plays the personal against the political in a time of change. /

He was an exemplary presence in our literary culture, warmly engaged as a reader and someone who loved painting as well as poetry. He was fully social when that was required and then ready to withdraw, be quiet, get on with his reading and his work and his living the life of the mind, exploring his own immense talent as a poet and novelist.’Available at The irish Times - online; accessed 28.12.2022.

Dermot Bolger

In any society certain gifted writers exist who are as essential and sometimes as unnoticed as plankton. Philip Casey was never an unnoticed presence in Irish writing, but – through his poetry and novels – was most certainly an essential presence. He was a writer’s writer, a man deeply respected by his peers and by shrewd connoisseurs of Irish fiction, but someone who – as the quiet man of Irish writing – perhaps never received the public acclaim that his work, most especially his rrilogy of novels, deserved. This made the novels and poems an even more unexpected pleasure for those who encountered them.

His acclaimed debut, The Fabulists, remains a remarkably evocative picture of 1990s Dublin with its story of love on the dole and its two superbly drawn protagonists: Tess, who has descended into despair since her separation, and Margo, who on the surface has little to offer Tess but the warmth of his vivid imagination. They conjure tales that draw them close together in a bittersweet examination of extramarital love and the realities of survival in a dowdy Dublin with no signs that a Celtic Tiger would transform it.

Other streets are definitely being transformed in Philip Casey’s second novel, The Water Star: the ruined streets of postwar London where Casey was born. Eighty per cent of Irish children born between 1931 and 1941 needed to emigrate. Casey’s parents were unexceptional in needing to leave Ireland in the late 1940s but were exceptional in being among the rare few emigrants able to return home to the remote Wexford farm where Casey grew up. His early memories of London’s bombed streets remained sufficiently vivid for The Water Star to work as a brilliant evocation of London in all its diversity, prejudice, redemption, wounds and rebirth. It captures the British and German experience of the aftermath of war, and the experience of the migrant Irish seeking rebuilding work there, who were initially overwhelmed by the scale of the city itself, never mind the devastation. In this ambitious book the torched buildings of Hamburg in RAF raids become as real as the improvised mountain slopes of Wexford that its main protagonists leave behind in their quest for economic survival.

But perhaps the most ambitious book is The Fisher Child. A blend of historical and contemporary drama with a cinematic edge, it ranges in time and location from present-day Italy, London and Wexford to the bloody 1798 Rebellion in Wexford and the slave plantations of Montserrat.

I was thrilled to see him enjoy recognition as a novelist but for me over the past 40 years he was first and foremost a very special poet. I was proud to publish three of his collections with Raven Arts Press, being fascinated to watch each book develop. Over that time I had my life enriched by the gift of his friendship. This week I feel I have lost someone with whom I had a truly unique friendship, but such was Philip’s gift for friendship that I know dozens if not hundreds of people today have exactly the same feeling. This was his great gift, to make all of our friendships with him feel unique by allowing us to walk away with our souls warmed by his generosity and wit, his fierce intelligence and integrity and by allowing us to share in his uniqueness so that we all walked away feeling taller and more special simply for having being allowed to spend special time with him.Available at The irish Times - online; accessed 28.12.2022

(See other tributes by Sebastian Barry, Paula Meehan, Theo Dorgan, Thomas Lynch, Katie Donovan, Rosie Schaap, Michael O’Loughlin, Eilean Ní Chuilleanáin, Anthony Farrell [Lilliput Press], Mary O’Donnell, Joseph O’Connor, Christine Murray, Eamonn Wall, Emer Martin, Gerard Smyth, Kevin Connolly, Maureen Kennelly, Pat Boran, Chris Clear, Anthony Glavin, Enda Wyley, Eoin O’Brien, Emma Cullinan [See online.]

[ top ]

Commentary

Paul Magrs, reviewing of The Fisher Child (Picador), recounts the plot: Dan’s wife Kate becomes pregnant on a visit to Florence, and bears a black child, Meg, which Dan rejects and sinks into a depression; his own father, living a new-age life in Co. Wexford, reveals that an ancestor Hugh as involved in the 1798 rebellion and fled to Montserrat where he became a small landowner and had three children with a black slave Ama, one a white boy and two others black girls, a family doomed to tragedy since she favours the boy; Dan achieve compassionate reconciliation and learns through a ‘rush of hurt; to appreciate the troubles of others. Magrs calls it a ‘wise, tender novel’ about the ‘muddled connections and continuities of [the characters’] lives.’ (Times Literary Supplement, 16 Nov., p.24.)

[ top ]

References

Katie Donovan, A. N. Jeffares & Brendan Kennelly, eds., Ireland’s Women (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1994), selects prose.

[ top ]

Quotations

1916 & All That: ‘It [visiting Kilmainham] was very moving, but I have long come to regard 1916 as an act of monumental foolishness, however undeniably heroic and noble. I believe their putative military descendants to be even more foolish. Ostensibly struggling to unite the island, they have before their eyes the evidence of what lies before them should they succeed. [/.../] I am proud to be Irish but that pride derives from a cultural source. I believe that Pearse and Connolly gave their lives for a political freedom which is of little benefit to the mass of the Irish people, its workings confined to meaningless arguments about non-issues and the clash of a few dominant personalities. Economic freedom has been tenuous and largely mythical. [... / ...] despite the pious rhetoric, the Easter Rebellion remains a pathetic waste of life.’ (Letters from the New Island, 16 on 16: Irish Writers on the Easter Rising, Raven Arts Press 1988, 47pp., Contribution [author name/no title], pp.28-29; p.29.)

‘Comforts of Youth’, in “Finishing Lines”, The Irish Times Magazine (14 Sept. 2002): ‘[...] The curlew in the bog and the gasmask in the [London] bombsite have followed me through life as emotional contradictions. It is like declaring something to be true, then immediately seeing that its opposite is also true. This is probably why I have trouble believing that three plus two is five, but can quite easily grasp that an electron can be in two places at once. That space and time are relative concepts sits quite easily with me. Yet the gasmask and the curlew have a peculiarly unvarying character. They are things as themselves, in a particular, fixed time. Even though a bird is hardly stationary, the curlew’s cry always seemed to come from the same part of the bog. Though I must have heard it many times, it is as if I only heard it once, perhaps because its two lonely notes etch themselves into the brain, like a nervous metronome. The gasmask, on the other hand, despite the fact that it had a history, that its owner had perhaps died horribly, seems now to have been more lifeless than any mask or any corpse.

Not so the third image which has followed me around since my youth like an umpire of the game between the curlew and the mask: Croghan mountain, the same mountain over which the rain inexorably crossed like a blind animal that knew where it was going. The word Croghan comes from the Irish cruachán, meaning stack, or small mountain, and there are many so named in Ireland. Like most mountains, it looks different depending on where you view it from, but from where I stood, near Hollyfort, it had the classic shape of a peak. In winter it was reminiscent of the mask: cold - indifferent it seemed, even to the curlew; as if by contrast on a fine summer’s day when it was exquisite to watch, it somehow cared for you, which is to say you could love it then. / On a fine day in summer it was fascinating, as it shimmered, apparently blue, and seemed to breathe. In a lovely poem, James Liddy called it the Blue Mountain. I think I must have projected my inchoate sense of the spiritual onto it, and it has been refining and offering it back to me ever since. / No doubt there lurks in some psychoanalysis or poetics handbook a name for these enchantments that one carries to the grave. Im convinced that everyone has at least one to which they return in times of reflection, or crisis, and it is always there, in the background, waiting to release its power if only its carrier will allow it. It is where empathy begins. If a term for such solaces exists, 1 dodt want to know it. In a way, I shouldn’t even be mentioning them here. They should be sacred and therefore secret. But ifs too late. They permeate everything I have ever written, and perhaps they always will.’ (p.66; end.)

| “An Indian Dreams of the River” (for Terry and Kevin) |

|

| —The Irish Times (27 Aug. 2015) in a feature-article on the publication of his Selected Poems. |

| “Machine Buried” |

|

| —From After Thunder (1985); quoted by Pat Boran in a tribute to Casey by Irish writers (The Irish Times, 5 Feb. 2018) - online; accessed 27.12.2022. |

[ top ]

Notes

The Fabulists (1994), set in Dublin, concerns Tess and Mungo, lonely people who begin sporadic affair after chance encounter on Ha’Penny Bridge having both been through ‘marriage, children, death of love’; exchange fantasies; rediscover capacity to feel; Mungo has previously lived in Barcelona; Tess receives postcards from Berlin; opens with Tess joining the Parade of Innocence to highlight the case of the Birmingham Six as it crosses O’Connell St. Bridge, where she first sees Mungo; ends with the couple waving to President Robinson as she leaves Dublin Castle following her inauguration; skill in handling of elements of fact and fantasy. (See review by Liam Harte, in Irish Studies Review, Winter 1994/5, p.49.)

The Fisher Child (2001) - author’s plot-summary: ‘Like [a] Renaissance painting [...] The Fisher Child is in three parts. In the first, Kate is happily married to Dan, both of them second-generation Irish and comfortable in their middle-class north London lives. They have two children, a boy and a girl, with another one on the way. But when Meg is born, Dan cannot accept her as his child, and retreats to Ireland in bewilderment. In Wexford, his family are partaking in the the bi-centenary commemoration of the 1798 Rebellion, and he learns about his ancestor Hugh Byrne, a rebel who was forced to flee Ireland, presumably to America. Dan will never know what the reader discovers in part two - that Hugh had not settled in America but in the Caribbean island of Montserrat, where he fell in love with Ama, a black slave whose genes have lain hidden in Dan’s family for two centuries.’ (Posted on Facebook, 20.01.2015 - at the Kindle launch of the novel.)

The Coupla (2015): Will Kate and Danny find their mother? A magical twist on the shape-shifting wonders of Irish myths and sea legends. Kate and Dan are twins. When they were three, their mother Ana walked into the sea. Cormac, their dad, and Mrs Janey who looked after them while he was away, both tried their best to comfort them, but they still missed her. [See Amazon.]

Irish wrongs: Casey wrote a manuscript entitled The Book of Rights: The Story of Irish Slavery & Servitude which was rejected by many publishers. (See Eoin O’Brien, tribute to Philip Casey, in The Irish Times, 5 Feb. 2018 - as supra.) His humanitarian side and sense of injustice for subject peoples is also noticed by Emer Martin in the tribute.

[ top ]