Life

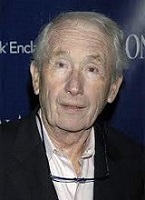

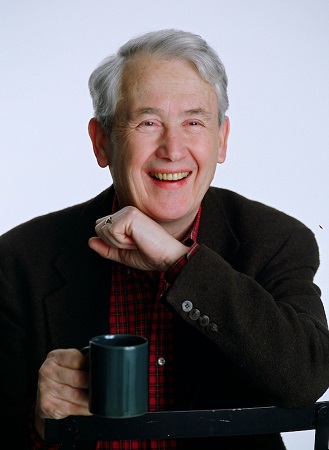

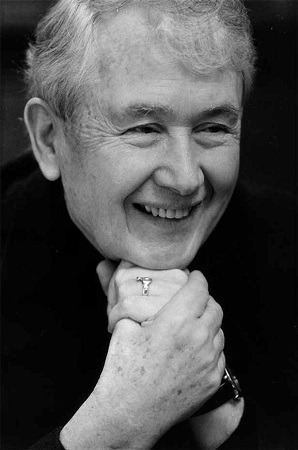

| (1930-2009); b. 19 Aug., in Brooklyn (NY), son of Malachi McCourt, a convicted IRA-man from Toome, Co. Antrim, and Angela [née] Sheehan; when an infant-dg. Margaret died, his father returned to drink and his mother fell into deep depression; family returned to Limerick, settling at Barrack Hill, 1934; raised with siblings Malachy, Michael and Alphonsus [Alfie] by their mother in various slum accommodations including Rodin’s Lane, featured in Angela’s Ashes, after the departure of alcoholic father to work at Coventry war-time England; came close to death with typhoid fever, and spent three months in hospital, 1940 [aetat. 10]; profited by its well-stocked library; effectively supported the family through odd-jobs on his release [aetat 11]; left school at 13 [var. 14]; |

| emigrated to America at 19; various early jobs beginning with hotel work at Biltmore Hotel; telegram boy; drafted into Army during Korean War and stationed in Germany, scheduled to dog-training; worked at docks on his return; noticed by a priest and grad. from at NY University on the GI Bill, 1957; became a school-teacher in New York, initially teaching unruly kids at McKee Vocational High School, Staten Island (‘I ate that sandwich’), and afterwards at Styvesant High School for 18 years, teaching 27 years in all; a life-long member of the American Federation of Teachers; also taught at Technical College of the NY City University; joined in NY by his mother in 1959; completed an MA at Brooklyn College, 1967; commenced a Ph.D. at TCD in 1971; suffered the death of his mother, 1982; |

| Bell Table Th., Limerick; frequently attended Willie Maloney’s “First Friday” writers’ lunches at Doran’s Bar, NY; associated with Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin in Irish-American bars; issued Angela’s Ashes (1996), a phenomenal best-selling account of childhood poverty in Limerick and ultimate emigration to America, at first as an extract in an issue of Here’s Me Bus (NY 1995); winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Award, the ABBY Award, and the Pulitzer Prize for Biography; held its place at the top of the New York Times best-seller list for 17 weeks; paperback rights sold for $1,000,000; film rights purchased by producers Scot Rudin and David Brown, and filmed in 1999 by Alan Parker (dir.); |

| issued ‘tis (1999), a sequel to Angela’s Ashes, relating the hero Frankie’s life in America and commencing with the last word of Angel’s Ashes; issuedTeacher Man (2006), memoirs of the years before Angela’s Ashes; read from his work at Belfast Cathedral Quarter Arts Fest., 1-12 May 2003; Malachy, his brother, became a film-maker and directed The McCourts of Limerick (1998); with Malachy, performed A Couple of Blaguards (Andrews Lane Theatre Jan. 1998); issued Angela and the Baby Jesus (2007), based on an incident in his mother’s childhood; |

| trice married and twice divorced; first to Alberta Small, with whom a dg. Margaret; then to Cheryl Ford, a psychotherapist, and finally to Ellen Frey McCourt, 1994; latterly lived at Roxbury, Connecticut, where he was a neighbour of Arthur Miller; appt. writer-in-residence in London, living at the Savoy Hotel; spent a term teaching the American Academy in Rome; audience with Pope John Paul II; received hon. doct. of University of Limerick; succombed to meningitis following hospital treatment for melanoma, and home chemotherapy; d. 19 July 2009, in a Manhatten hospice; survived by Ellen, his daughter Maggie, a granddaughter Chiara, two grandsons Frank and Jack, and his three brothers and their families. |

[ top ]

|

|

|

|

|

[ top ]

Criticism

|

Also Aoileann Ní Éigeartaigh, ‘Frank McCourt: from colonized imagination to diaspora’, in Ní Éigeartaigh, et al., eds., Rethinking Diasporas: Hidden Narratives and Imagined Borders (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholar Publishing 2007), q.pp. |

See also a letter by Noel Mulcahy The Irish Times (27 July 2009) recalling the McCourts in New York in the 1980s [online]; also an appreciation by Lev Grossman (Time, 19 July 2009; extract & online); Academy of Achievement notice [online]. |

| Video clips |

|

[ top ]

Commentary

John Walsh, ‘Escape from Losers’ Lane’, interview with Frank McCourt, Independent, Long Weekend, Sat. 12 July 1997, p.3, with photo-port.: ‘after his father left, the family hit rock-bottom’; recounts episode in Limerick book-launch when an unknown primary school classmate tore up the book, calling McCourt ‘a disgrace to Ireland, and the Church and your mother […]’. Walsh describes it as ‘a relentless, jaunty, chronicle of poverty, degradation and want.’ Mr Court insists that ‘all of this happened.’ Further: ‘I arrived in New York as damaged goods at 19’; overcame low self-esteem through years of teaching at Staten Island High School; ‘I survived because there was an empathy with the kids; I adapted to them rather than the other way around’; three brothers fell into alcoholism in America; joined by his mother in New York in 1959 (‘Every time I cross the floor, I’m tripping over little Jews and Protestants’) and d. 1982; a dg. became a ‘Dead-head’ following Jerry Garcia’s group around America.’

Seamus Deane, ‘Merciless Ireland’, in Guardian Weekly ([18] Jan. 1997), notes that ‘Malachy combines alcoholism, fecklessness, and a gift for storytelling that is, by now, an almost classical formation for a male of the Irish underclass. / It is the memoir’s strange combination of the remembered with the stereotypical that its appeal and its problems lie. Perhaps too much is remembered; or, more precisely, too much is told over and over again. The filth and the stench of unsanitary conditions, the starveling diet, the high incidence of grotesques and eccentrics, inhabit the lanes of Limerick, the endless prejudice of uneducated and prolific opinions about the world in general and the Irish world in particular ultimately have an eroding effect. […] McCourt is certainly a fine writer, but I wonder about his sense of economy. He believes too much in the reliability of memory as if that were enough in itself.’

Pascal Frey, Lire (Sept. 1997), quotes opening: ‘Pire que l’enfance misérable est l’enfance misérable en Irlande. Et pire encore est l’enfance misérable en Irlande catholique’, with remarks: ‘Terrribe critique de l’Irlande, violente condamnation de l’Eglise catholoqie, là-bas toute-puissante et méprisante, le récit de Frank McCourt, à mi-chemin du document et le l’ouevre littéraire, est un brûlante description de ce que doit être l’enfer, s’il existe. Comment guérir d’une telle enfance, comment réussir à pardonner à un père qui vous a abandonné pour écumer les bars d’Angleterre, comment surmonter la rancoeur qui vous submerge. Frank McCourt nous le confiera peut-être dans le livre qu’il est en train d’écrire, la suite des Cendres d’Angela ’. (p.70.)

R. F. Foster, ‘ ‘tisn ‘t: The Million-dollar Blarney of the McCourts’, review article on Angela’s Ashes; ‘ ‘tis; and Malachy McCourt, A Monk Swimming, in The New Republic (1 Nov. 1999), pp.29-32: Foster questions whether ‘all the facts are true’ as affirmed by McCourt in interview; points out indebtedness in certain episodes to McLiammoir, Joyce, Dostoeyevski, O’Casey, and so forth. Writes of ‘skewed powers of observation and fuzzy air of anachronism’; remarks that ‘one of the strange nullities at the heart of Frank McCourt’s autobiographies [is] ‘his lack of a sense of place’. Considers that he ‘confirms the traditional and comforting belief that the Old World is a sow who eats her own farrow, and everything will eventualy come right in America, along with creature comforts, blonde women, and hot running water. It fulfills the stereotype of the Irish as brawlers and boozers, excluded from the effete WASP world, at one with their fellow underdogs, with a tear and a smile always at the ready, and a miraculous way with words - as Malachy McCourt puts it, “warm words, serried words, glittering, poetic, harsh, and even blasphemous words.”’ (p.32).

Aisling Foster, review of ‘tis: A Memoir (Flamingo), in Times Literary Supplement (15 October 1999), equates the ‘tendency to allow fact and storytelling to overlap which Frank discovers in his father on remeeting him after many years with the gifts of the son.’ This is a classic immigrant’s tale which, despite its lack of colour, is definitively “Irish” [...] he has lived long enough with Wuncle Sam [viz, Uncle Sam] to know how to tell the stories that America wants to hear.’

|

||||||||||||||

John Banville, in interview with Marie Arana, ends by citing ‘a little quotation I’ve found’ in answer to the success of writers like Frank McCourt: ‘It’s from Neitszche, and goes something like this: “before you can get the crowds to cry Hosanna, you must ride into the city on an ass.” Isn’t that it, now. / Isn’t that just the way it is?’ (Washington Post, Book World, 19 Sept 1999, p.8.)

David Ansen, review of the film version of Angela’s Ashes, in Newsweek (20 Dec. 1999), remarks: ‘[it] will not offend any of the book’s legions of fans. Neither will it replace the original in anyone’s affections.’ Further: ‘Parker’s rainy, gray-blue images are artful and authentic looking, but still they can only be a pale reflection of McCourt’s lilting, sardonic prose. Significantly [...] it’s the narration that generates the emotion, not the scene itself.’ (p.25.)

Raphaëlle Rérolle, ‘La force d’un rêve: Après Les Cendres d’Angela’, review of C’est Comment l’Amérique?, in Le Monde (7 Avril 2000): ‘Franck McCourt relate, le plus souvent avec humour, sa lente ascension sociale en Amérique.’ ‘Franck McCourt doit son salut à son courage, mais aussi à l’amour de la littérature. Car la lecture de Dostoïevski, de Melville ou de Swift lui a ouvert une autre vie que celle des docks et des couloirs d’hôtels.’

Lev Grossman, ‘Frank McCourt, Author of Angela’s Ashes, Dies’ [appreciation], in Time (19 July 2009): ‘[...] For many years, McCourt tried and failed to write about his childhood. The family talent for storytelling kept him alive in the classroom, but he couldn’t get the words down on paper. He kept company in bars with writers like Pete Hamill and Jimmy Breslin, but his own voice stubbornly refused to emerge. The psychological weight of his past may have weighed him down. It also took a toll on his personal life; first one, then a second marriage ended in divorce. (He was married a third time, happily and permanently, in 1994.) He left the Catholic Church too, and the split was not amicable. “I was so angry for so long, I could hardly have a conversation without getting into an argument”, he said. “It was only when I felt I could finally distance myself from my past that I began to write about what happened.” / It was while he was babysitting his granddaughter — he had a daughter from his first marriage — that he had the idea of writing like a child: detached, simple, in the present tense. “I had this extraordinary illumination, or epiphany”, he said. “Children are almost deadly in their detachment from the world ... They are absolutely pragmatic, and they tell the truth, and somehow that lodged in my subconscious when I started writing the book.” / The result was his memoir Angela’s Ashes , which appeared in 1996, when McCourt was 66.’ [Accessed online; 02.08.2009.]

Alan Titley, ‘Turning Inside and Out: Translating and Irish, 1950-2000’, in Yearbook of Irish Studies (MHRA 2024): ‘I have never been in any bookshop in any country in any continent where I have not seen a translation of Frank McCourt’s execrable classic Angela’s Ashes. The only consolation is that the translation must surely be better than the original.’ (Available at Free Library - online; accessed 24.10.2025.)

[ top ]

| ‘The rain drove us into the church - our refuge, our strength, our only dry place ... Limerick gained a reputation for piety, but we knew it was only the rain.’ (Angela’s Ashes; quoted in Irish Culture and Customs, online - 23.03.2010.) |

Angela’s Ashes (1996), ‘When I look back on my childhood I wonder how I survived at all. It was, of course, a miserable childhood: the happy childhood is hardly worth your while. Worse than the ordinary miserable childhood is the miserable Irish childhood, and worse yet is the miserable Irish Catholic childhood. / People everywhere brag and whimper about the woes of their early years, but nothing can compare with the Irish version: the poverty, the shiftless loquacious alcoholic father; the pious defeated mother moaning by the fire; pompous priests; bullying schoolmasters; the english and the terrible things they did to us for eight hundred long years. / Above all - we were wet. / Out in the Atlantic Ocean great sheets of rain gathered to drift slowly up the River Shannon and settle forever in Limerick. The rain dampened the city from the Feast of the Circumcision to New Year’s Eve. It created a cacophony of hacking coughs, bronchial rattles, asthmatic wheezes, consumptive croaks [...]’ (p.1).

Angela’s Ashes (1996), ‘One night I’m sitting under Mrs. Purcell’s window listening to Macbeth. Her daughter, Kathleen, sticks her head out the door. Come in, Frankie. My mother says you’ll catch the consumption sitting on the ground in this weather. / Ah, no, Kathleen. It’s all right. / No. Come in. / They give me tea and a grand cut of bread slathered with blackberry jam. Mrs. Purcell says, Do you like the Shakespeare, Frankie? / I love the Shakespeare, Mrs. Purcell. / Oh, he’s music, Frankie, and he has the best stories in the world. I don’t know what I’d do with meself of a Sunday night if I didn’t have the Shakespeare. / When the play finishes she lets me fiddle with the knob on the radio and I roam the dial for distant sounds on the shortwave band, strange whispering and hissing, the whoosh of the ocean coming and going and the Morse Code dit dit dit dot. I hear mandolins, guiars, Spanish bagpipes, the drums of Africa, boatmen wailing on the Nile. I see sailors on watch sipping mugs of hot cocoa. I see cathedrals, skyscrapers, cottages. I see Bedouins in the Sahara and the French Foreign Legion, cowboys on the American prairie. I see goats skipping along the rocky coast of Greece where the shepherds are blind because they married their mothers by mistake. I see people chatting in cafés, sipping wine, strolling on boulevards and avenues. I see night women in doorways, monks chanting vespers, and here is the great boom of Big Ben, This is the BBC Overseas Service and here is the news. / Mrs. Purcell says, Leave that on, Frankie, so we’ll know the state of the world. / After the news there is the American Armed Forces Network and it’s lovely to hear the American voices easy and cool and here is the music, oh, man, the music of Duke [319] Ellington himself telling me to take an A train to where Billie Holiday [sic] sings only for me, “I cant give anything but love, baby, / That’s the only think I’ve plenty of, baby” …’ (Angela’s Ashes, p.319-20.)

[ top ]

Notes

Angel’s Ashes / ’Tis: Note the use of “ ‘tis” in the former as a recurrent affirmative refrain (p.162 & 426); also the recurrent use of sentimental song, viz - ‘love her as in childhood / Though feeble, old and grey. / For you’ll never miss a mother’s love / Till she’s buried beneath the clay.’ (p.5), and ‘A mother’s love is a blessing / No matter where you roam. / Keep her while you have her, / you’ll miss her when she’s gone.’ (p.420)

Frank McCourt, Angela and the Baby Jesus (London: Fourth Estate 2007): Angela steals the baby from the church crib because she thought he was unhappy; her mother makes her bring it back; arrives at Church to find Fr. Creagh with a policeman setting out finding out the thief.

Angela’s Ashes was filmed by Alan Parker in 1999 with Emily Watson as Angela; Ciaran Owens, Michael Legge, and Joe Breen as Frank at various stages; Emily Watson and Robert Carlyle as his parents; Shane Murphy Corcoran as his br. Malachy; literary agent Molly Friedrich (New York);

Belfast reading: Frank McCourt reads at Belfast Cathedral Quarter Arts Fest., May 1-12th 2003 at a special event to be held at the Harbour Commissioner’s Office.

Namesake: Frank and Jamie McCourt employed Vladimir Spunt to beam thought waves to boost the team’s chances [...] rarely in the history of America’s national game has there been anything quite like this. Frank and Jamie McCourt, the multi-millionaire owners of the LA Dodgers, have been revealed to have employed a Russian scientist to beam thought waves to boost the team’s chances. According to Bill Shaikin of the LA Times, the McCourts paid Shpunt several hundred thousand dollars over five years to apply his "V energy" and help the Dodgers to victory. Between 2004, the first season under the McCourts' ownership, and 2009, Shpunt was retained for Dodgers matches, despite the fact that he knew little about baseball. [...]. (See Guardian, 10 June 2010 [online at date]; and see PZ Myers thoughts on Scienceblogs.com [online].

[ top ]