Life

| 1912-68 [fam. “Don”]; b. 22 Nov., Temple Villas, Rathmines, Dublin, son of Thomas MacDonagh (d. 1916; q.v.) and Muriel [née Gifford, a Protestant family, and sister of Grace Gifford, Republican cartoonist]; Muriel drowned through exhaustion while swimming from Skerries to Lambay, 9 July 1917; Donagh raised by Jack MacDonagh and by Eleanor Bingham, Co. Clare; infected by live TB vaccination, 1917, leading to frequent hospitalisation and causing stunted growth and scholiosis; ed. initially by various lady teachers and finally at Belvedere College from aetat. 12; entered UCD (Arts) and studied with contemporaries Niall Sheridan, Denis Devlin, Cyril Cusack, Brian O’Nolan [Flann O’Brien], Charlie Donnelly, and Mervyn Wall [all q.v.]; |

| passed his second year at the Sorbonne; served as Sec. of English Lit. Soc. (UCD) and staged first Irish production of T. S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral in Dublin, with Liam Redmond, later his brother-in-law (m. Barbara MacDonagh) - being attended and highly praised by the author himself (who was invited to act as a stage-hand; completed MA on Eliot; attended Kings Inns, Dublin, concurrently with UCD; with Niall Sheridan, issued Twenty Poems (1934), receiving good notices in Irish and British papers; m. Maura Smyth, 1934, with whom two children (Breifné and Iseult) and who drowned in her bath during an epileptic fit, 1939; called to Irish bar 1935; not burden with many briefs and essentially unemployed until he was appt. District Justice in Co. Wexford, 1941; acted as a popular broadcaster on Radio Éireann from 1939, hosting “Ireland is Singing” - a showcase for folk-songs and ballads; |

| issued Veterans and Other Poems (Cuala Press 1941) - less well received than the former; suffered depression as a single parent, before marrying Nuala Smyth, Maura’s sister, and mother of his children Niall and Barbara, 1943, living as a family at Strand Rd., Dublin; appointed to the bench in Dublin where he worked up to his death; Brian O’Nolan broke off his friendship with MacDonagh when the latter refused to try case brought against him; edited the Irish Times Book Page, and issued Poems from Ireland (1944), with an introduction; wrote poetic dramas and ballad operas; issued The Hungry Grass (1947); published Happy as Larry (1946), a ballad-opera; praised by Valentin Iremonger in a review challenging Irish theates to produce it - leading to a production by the Belfast Lyric Th. Co. on the Abbey stage in Dublin (May 1947); transferred to Mercury Th., (London), where it became the most successful play in post-war years, went on to be staged at the Criterion Th., (Londond West End, 1948), but was staged unsuccessful in New York in an elaborate musical production by Burgess Meredith (1950); |

| adapted Jean Anouilh"s Romeo and Juliet as Fading Mansion (Duchess Th., London, Sept. 1949) - a d´e;but vehicle for Siobh´a;n McKenna but otherwise unsuccessful; wrote God’s Gentry, a frequently acted but unpublished play about tinkers [travellers], premiered at Belfast Arts Theatre, Aug. 1951 and transferred to the Gate for a record-breaking nine weeks; his Step-in-the-Hollow (Gaiety Th., 11 March. 1957) is a court-room comedy; ed., with Lennox Robinson, Oxford Book of Irish Verse (1958); adapted the Deirdre story as Lady Spider (Gas Co. Th., Dun Laoghaire, Sept. 1959); d. 1 Jan. in Dublin, of lung failure; a last collection A Warning to Conquerors (1968) published posthumously; bur. Deansgrange Cem.; his best-known poems include ‘‘The Hungry Grass’’ and ‘‘Dublin Made Me’’; collaborated with Louis le Brocquy in water-coloured broadsheets based on Happy as Larry; there is a bust by Oisín Kelly; there is no critical biography. NCBE DIB DIW DIH DIL FDA OCIL |

| Letters written by Thomas MacDonagh, 32 Upper Baggot Street to Donagh MacDonagh, addressed care of Muriel MacDonagh, on the occasion of his birth and on the day he was one month old.

Letters are full of fatherly pride and wishes for the future, “I must myself formally congratulate you on having such a mother. You are the most fortunate child in the world, as I am the most fortunate man. Please God we three are going to have a long and happy and loving life together.” [2 items, with envelopes /

22 Nov and 22 Dec 1912; contained in Thomas MacDonagh Family Papers held in National Library of Ireland [NLI] as as MS 44,318-MS 44,345 - available as a PDF catalogue compiled by Harriet Wheelock (2008) - online. A few of Donagh McDonagh’s papers are also listed on p.45. |

The site incorporates PDF copies of the majority of his works. |

[ top ]

Works| Plays |

|

| Poetry Collections |

|

| [ top ] |

| Miscellaneous [chiefly anthols.] |

|

| See also Donagh MacDonagh, ‘The Death-watch Beetle’, in Abbey Theatre: Interviews and Recollections, ed. E. H. Mikhail (London: Macmillan 1988), pp.184-88. |

| Broadsheets |

|

[ top ]

Bibliographical details

Poems from Ireland, ed. with an intro. by Donagh MacDonagh; preface by R. M. Smylie (Dublin: Irish Times 1944), 91pp; also Biographical notes, pp.xiii-xvii, covering G. M. Brady; Rev. Patrick Browne; Joseph Campell; Austin Clarke; Rhoda Coghill; Maurice Craig; John Lyle Donaghy; Lord Dunsany; Padraic Fallon; Irene Haugh; George Hetherington; John Hewitt; F. R. Higgins; Valentine Iremonger; Fred Laughton; A J Leventhal; C. Day Lewis; Donagh McDonagh; Roy McFadden; Francis McManus; Brinsley MacNamara; Louis MacNeice; Ewart Milne; Myles na gCopaleen; Frank O’Connor; Roibeárd Ó Faracháin; Seumas O’Sullivan [sic]; W. R. Rodgers; Richard Rowley; ‘Michael Scot’ [sic]; Niall Sheridan; W. B. Stanford; Sheila Steen; L. A. G. Strong; Francis Stuart; Geoffrey Taylor; Peter Wells; W. B. Yeats [see Bibliographies, “Anthologies”, infra].Four Modern Verse Plays (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books 1957), 269pp. Contents: Charles Williams, “Thomas Cranmer of Canterbury”; T. S. Eliot, “The Family Reunion”; Christopher Fry, “A Phoenix too Frequent”; Donagh MacDonagh, “Happy as Larry”.

Love Duet: from the play God’s Gentry, by Donagh MacDonagh; decorations by Louis Le Brocquy [Dolmen Ballad Sheets, B3] (Dublin: Dolmen Press 1951), 1 sh., ill., 37 x 25cm. [To be sung to the tune of “One morning in May”; Set and printed by hand; ltd. edn. of 525 copies; UL copy signed]. Note: A framed copy is held by Melanie le Brocquy; part of a ltd. edn. of 525 copies, of which 25 are hand-coloured and signed. Uncoloured copies were published on St Stephen’s Day, 1951, for the opening of the author’s play God’s Gentry at the Gate Theatre (Dublin), and offered for sale at there during the run of the play. a broadsheet of verses from Happy As Larry, ill. and hand-painted by Louis le Brocquy is extant.

Note: Some papers incl. in “Thomas MacDonagh Family Papers” held as MS 44,318-MS 44,345 - available as a PDF catalogue compiled by Harriet Wheelock (2008) - online.

[ top ]

Criticism

|

See also Irish Book Lover 30. |

[ top ]

Commentary

Poems from Ireland, ed. by MacDonagh with a preface by R. M. Smyllie (Dublin: The Irish Times 1944), incl. an autograph notice on the editor-contributor, ‘Donagh MacDonagh has published verse in Ireland, England, Scotland, and America; a barrister, a student of history, a broadcaster, his latest book of verse was Veterans, published by Cuala Press.’

| At Swim-Two-Birds - MacDonagh is the subject of a sketch (or caricature?) in Flann O’Brien's 1939 novel: ‘The small man had an off-hand way with him and talked in jerks [...] We talked together in a polished manner, utilising with frequency words from the French language, discussing the primacy of America and Ireland in contemporary letters and commenting on the inferior work produced by writers of the English nationality. The Holy Name was often taken, I do not recollect with what advertence.’ (Quoted in Bridget Hourican, ‘Donagh MacDonagh’, in Dictionary of Irish Biography, RIA/Cambridge UP 2009) - available online. |

E. Martin Browne, ed., Three Irish Plays (Harmondsworth: Penguin 1959), incls. Donagh MacDonagh, Step -in-the-Hollow [pp. 165-236]. Browne’s Introduction notes that MacDonagh is ‘the son of one of the martyrs of the Easter Rising of 1916, and is a District Judge in the Irish courts.’ Further, ‘This proves useful as a background of knowledge to the racy tale of a judge who is a good deal more of a rogue than most of those he tries. Step-in-the-Hollow is an outrageous farce in the Falstaffian vein, with a hero as amoral, and as funny, though never as touching, as the Fat Knight. It was first staged by Hilton Edwards, who with Michael MacLiammoir has for many years provided in his Gate Theatre management the breadth of civilisation which the Abbey failed to give, without the loss of any of that exuberant vitality which Irish actors can provide. The play was a great success with Edwards as the Judge ... here printed for the first time. Laughter of the scale evoked by Step-in-the-Hollow is rare, and will be enjoyed with gratitude.’ [Note var., Martin E. Browne.]

John Montague, ‘The Impact of International Modern Poetry on Irish Writing’, in Irish Poets in English: The Thomas Davis Lectures on Anglo-Irish Poetry, ed. Sean Lucy, Cork: Mercier Press 1972): ‘[... H]ere we strike against a dismaying aspect of our literature, our tendency to regress from an advanced position. Thus Mac Donagh’s early work was intellectual and urban (he wrote his M.A. thesis on Eliot) but he gradually retreated to a simplified version of the Irish tradition. Again I am not saying that Ezra Pound is necessarily more important than Egan Ó Rahilly for an Irish poet (one has to study both) but the complexity and pain of The Pisan Cantos are certainly more relevant than another version of “Preab San Ól”.’ (p.153.)

Anthony Cronin, Laughing Matter: The Life and Times of Flann O’Brien (London: Grafton 1989), writes of ‘Donagh MacDonagh, son of martyred 1916 leader, also a poet, law student who, later in life, found it temptingly easy to claim an inheritance in the new order as a District Justice.’ (Cronin, op. cit., 1989, p.55).

[ top ]

Quotations

“My Grandfather was Irish”, in Penguin New Writing, 19 (Oct.-Dec. 1944), pp.55-63: ‘“My father, your Grandfather, the old fellow we’ve just left in his lonely grave, was a smallholder in his young days, not two miles from here. Above opposite the churchyard. He had a five acre farm and a little cottage and damn the thing else only a couple of cows, a pig or two, and a few chickens. Himself and my mother were married three or four years, and though they the grandest-looking pair in the country they hadn’t a sign of a family. Nobody could understand it al all. When the farm work wasn’t too hard he used to do a bit of work on the roads, breaking stones, or spreading them, or clearing ditches and the like. I believe he was a fair devil for stonebreaking and a great man at the game. He had a pal called Peter Joyce, a fellow abut the same age as himself, who used to be on the road with him. A great man for the beer he was. Of course my fad used to have a great mouth on him for it too before he got married, but after that he laid off it all right. Barring, of course, the occasional pint. / Well, one fine night anyway,’ me bould Peter Joyce, Josie Conway and a lad called Jack Taylor were out on a terrible skite down the local pub - Mulcahy’s it was, we’ll pass it a bit up the road here. They rambled in there about five in the evening with five or six shillings each in their pockets, - that was a lot of money in those days. They started drinking porter and they drank till it came out in their eyes. They were sitting there drinking and talking and singing, telling stories and cutting the bowels out of every mother’s son in the ten parishes. There wasn’t a girl in the county could escape their tongues, and to hear them talking you’d think they’d seduced every woman this side of the Shannon. /“Jack!” said my mother. “Remember the children”.’ [...]. For full-text version, see RICORSO > Library > “Various Irish Writers” - via index, or as attached.

Irish poetry in English: ‘Where Irish poetry in English is going in the future it is not easy to guess - every child who faces the microphone in a Gaelic “quiz” programme is able to give a thumbnail history of Gaelic poetry, to quote long passages from eighteenth century poets and to sing long and complicated Irish songs. The study of English literature in the schools has become a subject with the same importance as French or latin instead of the major subject which it once was, and the majority of teaching is completely through Irish. In these circumstances it seems reasonable to suppose that either a new native poetry will begin to develop, or, at the very least, poetry written in English will show ever more signs of the Gaelic influence. Already many of the older poetrs and most of the younger ones are able to use Irish as a second language, a fact which is obvious in such poems in this collection as Joseph Campbell’s Butterfly in the Fields, Austin Clarke’s The Blackbird of Derrycairn, Padraic Fallon’s Mary Hynes, Roibeárd O Faracháin’s The King Threatens the Poets and the translations of Myles na gCopaleen and Frank O’Connor, and perhaps it is as well that our poets should concentrate on doing what they do supremely well writing verse which is demonstrably non-English, rather than emulating something that English poets can do very much better.’ (See further under Bibliographies, “Anthologies”, [ infra].)

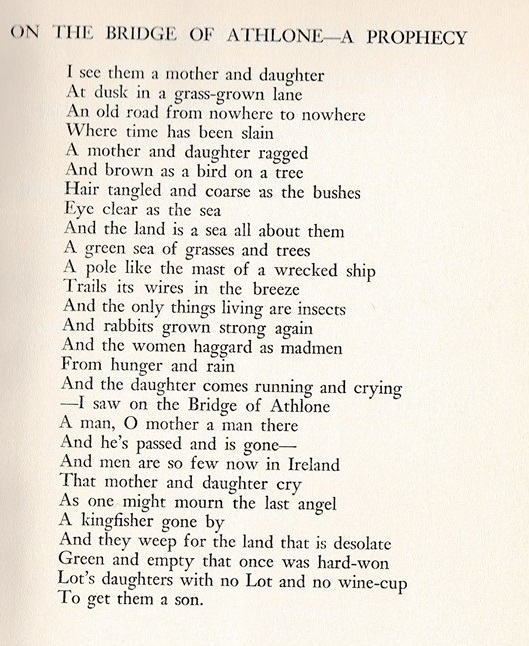

Posted on Facebook by Niall MacDonagh (25.09.2018.)

[ top ]

References

Robert Hogan, ed., Dictionary of Irish Literature (Dublin: Gill & Macmillan 1979), cites also God’s Gentry; ‘essentially theatrical rather than literary ... tremble on the verge of doggerel ... a similar thinness in his verse’.

Seamus Deane, gen. ed., The Field Day Anthology of Irish Writing (Derry: Field Day 1991), Vol. 3, 248, 498n, 657 [no extracts], Donagh MacDonagh’s famous poem, ‘Dublin Made Me’, appeared in The Hungry Grass (Faber 1947). BIBL, unpublished play in 3 acts, God’s Gentry, 68pp. [De Burca Cat. 18 £95.00].

John Montague, ed., Faber Book of Irish Verse (London: Faber 1974), incls. “Hungry Grass”; “Prothalamium”.

Grattan Freyer, Modern Irish Writing (1979), incls. “The Day Set for Our Wedding”; “Going to Mass Last Sunday”; “Dublin Made Me”, and “A Warning to Conquerors”.

Helena Sheehan, Irish Television Drama, A Society and Its Stories (RTE 1987), lists All the Sweet Buttermilk (1969), dir. Michael Bogdanov, adpt. Normany Smythe; God’s Gentry (1974), Donagh MacDonagh/Noel O’Brien [217]; Happy as Larry (1966), dir. Jim Fitzgerald [100].

[ top ]

Notes

High-class: is protrayed as Donaghy in Flann O’Brien’s novel At Swim-to-Birds (1939), as follows: ‘[he was] fast acquiring a reputation in the Leinster Square area on account of the beauty of his poems and their affinity with the high-class work of another writer, Mr Pound, an American gentleman […]. We talked together in a polished manner, utilizing with frequency word from the French language, discussing the primacy of America and Ireland in contemporary letters and commenting on the inferior work produced by writers of the English nationality.’ ([Penguin Edn. 1986, p.45].)

Austin Briggs, ‘The First International James Joyce Symposium: A Personal Account’, in Joyce Studies Annual, Summer 2002, pp.5-31: ‘McDonagh’s paper tells of lucky discovery of the text of “The Lass of Aughrim”, verses which Bartell D'Arcy sings with profound consequences in “The Dead”. At very moment MacDonagh reading letter of Joyce’s that mentions the ballad, daughter entered singing “Lady Gregory”, which he immediately recognised as variant of “Lass of Aughrim”. MacDonagh introduces his daughter Pretty teenager in pink dress, Barbara MacDonagh appears incongruous in this gathering of knowing university students and rather innocent-looking professors. Seating herself on stool, tunes her guitar for a moment, then delivers “Lady Gregory”. Voice untrained, but each note placed [17] precisely and discretely in small, clear soprano; Irish phrasing sad and sweet. This is what many of us have come to Ireland to hear.’ (p.17.) Remarks that MacDonagh irritated the other paper-givers by getting his printed in large part in Hibernia.

Wonderful: ‘Don was wonderful with children; no matter what age you were he spoke to you as if you were an adult, an unusual thing at the time.’ (Memoir of John Garvin, provided by Tom Garvin [his son].)

Namesake author?: Martha Graham: A Biography (NY: Praeger 1973), x, 341pp.; The Rise and Fall of Modern Dance (NY: Dutton 1970).

Sources: Details of his marriage to Maura and Nuala Smyth [in Life, supra] have been provided by Niall MacDonagh, a son.

[ top ]